Volume 24, No. 2, Art. 19 – May 2023

Looking for the Bigger Picture. Analyzing Governmentality in Mosaic Mode

Olaf Tietje

Abstract: In this article, I propose a mosaic mode of qualitative analysis that is focused on how social order and regulations are established in a society. In this way researchers can analyze society as a whole and reconstruct how people govern and are governed by mapping social worlds/arenas and situations in an iterative-cyclic mode.

Key words: governmentality; racialization; situational analysis; social order; social participation; social worlds

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The Neighborhood of Wilhelmsburg

3. Social Worlds/Arenas and Social Order

3.1 Social worlds/arenas

3.2 Social order and governmentality

4. Analyzing in Mosaic Mode

4.1 Towards the bigger picture

4.2 Putting the pieces together

5. Conclusion

"Thus, it may be that an African mother with a buggy

finds herself next to the Turkish grocer from the corner

and a student from Oldenburg with a jute bag.

The clash of cultures brings with it both the potential for conflict and many interesting snapshots from daily life."1)

Taken from the official website of the northern German city of Hamburg, this short quote is part of a description of Die Wilde 13 [The Wild 13], a documentary dealing with the Hamburg neighborhood of Wilhelmsburg, produced by the German anthropological researcher Kerstin SCHAEFER and the German producer Paul SPENGEMANN (2013). The film is about the Number 13 bus, which connects different parts of Wilhelmsburg and is nicknamed by the anthropologist after the pirates of the "Jim Button" series by Michael ENDE (1990 [1960]), a popular German author. In that book, the "Wild 13" are a band of foolish but ultimately kind pirates who carry out kidnappings and thefts all over the world until they are brought to heel by Jim Button and Luke the Engine Driver. The quote was used by the Hamburg authorities on an advertising notice for the documentary on the Number 13 bus. Those four lines highlight the neighborhood's image, and the way discourses are produced on so-called "immigration districts"—also known as "problem districts" in Germany (CHAMBERLAIN, 2020, p.2; see also BOLDT, 2020). The neighborhood of Wilhelmsburg becomes a place where different social groups are produced and homogenized as cultures (the "African mother," the "Turkish vegetable seller," and the "student from Oldenburg") existing next to each other, which bears the potential for conflict on the one hand and for "interesting snapshots" from life on the other. The author of the quote differentiated between people's backgrounds by continent, nation, and city—garnished with supposedly typical attributes ("buggy," "vegetables," "jute bag")2)—, pointing to a discursive racialized and gendered reading of immigrants in Germany (DIETZE, 2016, p.95; EL-TAYEB, 2016, p.8). [1]

In this article, taking the example of the neighborhood of Wilhelmsburg, I will show how researchers can analyze society through a mosaic of social worlds/arenas and study the bigger picture of social order. Based on the ideas of Anselm STRAUSS (1978) and Adele CLARKE, Carrie FRIESE and Rachel WASHBURN (2018), my aim is to demonstrate how to analyze governmentality, regulation, and control through social worlds theory in situational analysis. Situational analysis is already prepared for this kind of analysis because of its pragmatist background linked to postmodern theory (TIETJE, forthcoming). I am following the thesis that researchers can use mappings of social worlds/arenas to analyze the social relations affecting the subjects of research, while at the same time retracing the pathways of power (OFFENBERGER, 2019, §21). Researchers will be able to look for the links between individual practices and discourses, forms of subjectification and normative attributions. [2]

I produced the empirical data by conducting guided interviews (eighteen as of now) with a focus on the relevance of the interviewees (HOPF, 2016, pp.47ff.). Following a theoretical sampling strategy (STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1996 [1990], pp.148ff.) the interviewees were activists, counselors, residents in the Wilhelmsburg neighborhood, members of associations, members of small cooperatives and social workers. I also used participant observation to understand practices in the research field (OCEJO, 2013; SCHÖNE, 2003). For publication, I anonymized the interviewees or reduced the data to the respective organization for citations.3) I analyzed the data following the situational analysis and its suggested mapping procedures (CLARKE et al., 2018). Since 2021, I have conducted my research in the two cities of Barcelona and Hamburg. In this article, however, I have decided to focus solely on my research in Hamburg, to reduce its complexity. [3]

To this end, I will briefly introduce the background of the Hamburg neighborhood of Wilhelmsburg (Section 2). Afterwards, in Section 3, I will present my reading and methodological understanding of social worlds, governmentality and the possibilities of analyzing regulation and control with the research strategies of situational analysis. In Section 4, I will very briefly present some aspects of the research I am carrying out in the Hamburg neighborhood of Wilhelmsburg.4) Finally, I will close the article with a couple of brief conclusions (Section 5). My main argument is that by analyzing social worlds/arenas, researchers can grasp a larger, continuously changing picture in which not just subjectivities and discourses but also agency are rendered visible. [4]

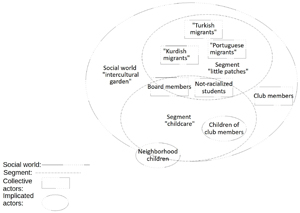

2. The Neighborhood of Wilhelmsburg

For my research in Wilhelmsburg, I am following an urban transformation plan called Sprung über die Elbe [Leap Across the Elbe]5) and the accompanying debates on participation by the residents of Wilhelmsburg (CHAMBERLAIN, 2020, p.2). The neighborhood is home to 54,068 people, of whom 20% are under 18 and 32% are foreigners without German citizenship; 60% of the residents are recorded in the statistics as having a "background of migration,"6) almost double the Hamburg average. The unemployed make up 8.4% of the population (4.8% in Hamburg as a whole) and 20.6% receive benefits under the rules of the Sozialgesetzbuch II (SGB II) [Second Book of the Social Security Code]7) (STATISTISCHES AMT FÜR HAMBURG UND SCHLESWIG-HOLSTEIN, 2019, pp.48f.). In addition to this socio-economic data, 12% of children in Wilhelmsburg leave school without any educational qualifications (INSTITUT FÜR BILDUNGSMONITORING UND QUALITÄTSENTWICKLUNG, 2016, p.28). In the neighborhood, 23% of all apartments are reserved for social housing; three times the figure in the urban area as a whole (7.9%) (STATISTISCHES AMT FÜR HAMBURG UND SCHLESWIG-HOLSTEIN, 2019, p.49). [5]

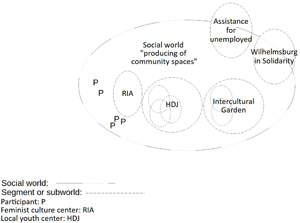

The leadership of the city of Hamburg recognized the need for transformation at the beginning of the 21st century and set out its vision of a growing city that should become an internationally visible metropolis (CHAMBERLAIN, 2020, pp.6f.; FREIE UND HANSESTADT HAMBURG, STAATLICHE PRESSESTELLE, 2002). Hamburg initialized the "Leap Across the Elbe" as one part of linked development planning in the area (FREIE UND HANSESTADT HAMBURG, BEHÖRDE FÜR STADTENTWICKLUNG UND UMWELT, 2005; HELLWEG, 2007). This transformation of the neighborhood of Wilhelmsburg was accompanied by enormous building projects and a renewal of housing structures. Apart from the negative effects of the gentrification (such as displacements or rising rents), it also brought with it investments in education (e.g., for the district schools) and local infrastructure (e.g., the renewal of local parks) (IBA HAMBURG GMBH, 2017; PERGANDE, 2013; VON KALBEN, 2018). [6]

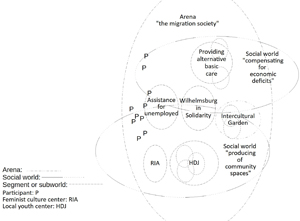

The renewed local parks form a unit that is central to the community understanding of the people living in Wilhelmsburg. As one of the interviewees said about Sanitas Park8): "It is also a space where everyone who lives here in Wilhelmsburg comes together. It is not a place like many others, where only the privileged come together" (interview resident of Wilhelmsburg, Hamburg, June 22, 2021).9) Those spaces, labeled as more exclusive, worry the residents of Wilhelmsburg. Due to the construction projects of the ongoing Leap Across the Elbe, fallow land, garden plots and other freely accessible spaces in the neighborhood are transformed into housing spaces—with very likely higher rents and correspondingly higher earning tenants (CHAMBERLAIN, 2022, pp.137ff.; LEMBKE, 2017). At the same time, with those construction projects new spaces and opportunities for the inhabitants of the neighborhood are produced. I take this tense situation with different levels of exclusion as a starting point for my analysis. [7]

3. Social Worlds/Arenas and Social Order

In the previous section, I described the neighborhood of Wilhelmsburg and referred to some of the changes happening in the district. In the following subsections, I will first argue that social worlds/arenas are constituted around at least one core activity. Because "all human activity [...] involves the joint activity of a number, often a large number, of people" (BECKER, 1982, p.1), I argue that social worlds should be focused upon as collective actors. Following Adele CLARKE and Susan Leigh STAR (2008), analyzing those collective actors enables researchers

"to understand the nature of relations and action across the arrays of people and things in the arena, representations (narrative, visual, historical, rhetorical), processes of work (including cooperation without consensus, career paths, and routines/anomalies), and many sorts of interwoven discourses" (p.113). [8]

Afterwards, I will turn to governmentality following Michel FOUCAULT (1992 [1990]) and investigate how its analysis is already inherent in the pragmatist background of social worlds/arenas theory.10) Starting from an "epistemological break" (MARTTILA, 2013, §4), an analysis of social order can be a very productive element of the analysis of the mosaic of social worlds. [9]

In 1938, Louis WIRTH proposed that cities and their segregation should be analyzed as "a mosaic of social worlds in which the transition from one to the other is abrupt" (p.15). While his notion of social worlds is reduced to the geographical segments of a city, I argue that the idea of a mosaic should be widened, with a more postmodern reading of social worlds (CLARKE, 2003, p.556). Social worlds—inspired by Anselm STRAUSS (1978)—are produced by the actors within, around a certain activity. My main research interest is how social worlds shape, establish and regulate activities, actions and interactions. Social worlds (or rather the analysis of social worlds) "provide a means for better understanding the processes of social change" (p.120). This direct link to the tradition of the Chicago School highlights the anti-deterministic thinking of an analysis of social worlds, or as STRAUSS put it:

"In short, I am suggesting that this Meadian 'fluidity' and the interactionists' general emphases on antideterminism and group encounter at any scale or scope be worked through for its implications, rather than restricted to certain kinds of groups of processes, and certainly not restricted to 'micro' or 'macro' studies of these matters. I believe that one means for doing that job is to study worlds and to take 'a social world perspective'" (p.121). [10]

The core activity constituting the social world must be relevant to all members of the respective world (CLARKE & STAR, 2008, p.118; STRAUSS, 1978, p.122). Within each social world, different issues are discussed, negotiated, and dealt with. Both the issues and the disputes around them are in some cases known and effective beyond the respective social worlds, and in some cases only known to the members of a specific world (STRAUSS, 1978, p.124). In contrast to the idea of "small life-worlds"—like for example Benita LUCKMANN (1970, p.581) described her units of analysis—thinking about social worlds involves an understanding of acting, and of living together, that extends beyond functionalist thinking. The members of a social world are not necessarily aware of the social world or its other members. Nevertheless, social worlds are constituted by individual actors affiliated with others, pursuing a common agenda. The members of a social world share common interests, worldviews, and commitments to types of action. They are aware of others within the social world and are oriented by the same discourses and ways of being on the specific theme of the respective social world (CLARKE & STAR, 2008, pp.113ff.). In the words of STRAUSS, those groupings are "a diffused and complex collective act into which numerous participants enter—whether or not they are aware of so doing" (1969 [1959], p.159; see also BECKER, 1982, p.36). Those worlds are adjacent to other social worlds (in processes of analysis) and may produce subworlds. Some of the social worlds may intersect, and there are no strict borders limiting them (BECKER, 1982, p.35; CLARKE, 1991, p.133; CLARKE & STAR, 2008, p.118; STRAUSS, 1978, pp.122f.). [11]

The sites where the different social worlds intersect, where their borders are negotiated, are social arenas. Structural changes in social worlds arise from "conflict, competition, negotiation, and exchange" (CLARKE, 1991, p.133).11) While the structures of social worlds are highly fluid, arenas form across various intersecting or tangent social worlds: "In arenas, all the social worlds that focus on a given issue and are prepared to act in some way come together" (ibid.). Issues are fought out in social worlds, subworlds and segments, involving political activity (but not necessarily legislative). Those issues can be manipulated not just by members of the social worlds or representatives but also by representatives of other (sub)worlds: "Wherever there is intersecting of worlds and subworlds, we can expect arenas to form along with their associated political processes" (STRAUSS, 1978, p.124). [12]

Arenas exist as spaces for conflict processing and "are central to the creation and maintenance of social order" (STRAUSS, 1993, p.227). In this understanding, I read social arenas as discursive sites that endure for a certain amount of time. Those arenas that exist for longer periods are constituted by complex and layered discourses related to contemporary and historical practices. Researchers must follow the empirical questions "Who cares?" and "What do they want to do about it?" (CLARKE, 1991, p.133) in order to reconstruct social arenas. Mapping social worlds/arenas like CLARKE et al. (2018, p.148) suggested allows researchers to focus on the negotiated issues, the relevant actors and their actions. Methodologically, this means that to understand social worlds, it is necessary to understand the arenas in which the social worlds are active. Those sites (of contestation, negotiation, and controversy) exist across social worlds and reveal different perspectives, positions, and power relations (ibid.). [13]

3.2 Social order and governmentality

One important characteristic of membership in a social world is the tendency on the part of members to adhere to and to act in accordance with a specific shared worldview. They engage in discursive constructions of matters of concern related to the social world constituting action (CLARKE & STAR, 2008, pp.118f.). Researchers can carry out analyses focusing on how the members of a social world act according to those worldviews. This aspect refers directly to the way subjects use certain techniques of the self and the question of how—i.e., by what means, instruments, tactics and procedures—authority and modes of government are established (TUIDER, 2007, §11). I understand governing and being governed as experiences (DEWEY, 1980 [1934], p.50) providing a link between situational analysis and studies of governmentality. Governing is not practiced by individuals but is a form of government thinking established within a society through discourses, techniques, and practices (FOUCAULT, 2005 [1994], pp.256f.). This government thinking develops its own dynamics based on its historical contexts. Those dynamics are in turn related to the individuals themselves (TIETJE, forthcoming). [14]

Current forms of neoliberal government in Europe are closely linked to an individual recognition of the necessity of government. At the same time, government should remain as limited as possible and allow as many individual freedoms as possible (FOUCAULT, 1992 [1990], p.12; SARASIN, 2019, p.13). This is connected to how and in what form states and societies are organized. This form is currently determined above all by governmental apparatuses that are linked to certain types of knowledge. The state as such is no longer to be considered a superior power, but instead functions as an administrative instance. In this reading, government means the way in which fields of action are structured. As a technique of leading, government affects other people as well as oneself: it is simultaneously about leading others, about being led and about different techniques of leading oneself (FOUCAULT, 2005 [1994], pp.256f.; LEMKE, 2002, p.52; TUIDER, 2007, §11). Fields of action are those spaces of possibility that discursively generate and frame individual and social scopes of action. These are never completely pre-structured or structured; ambiguous moments of freedom remain where individual subjectivities are still unpredictable (BUTLER, 1993, p.124; FOUCAULT, 2005 [1994], p.257). One question that arises to researchers is: What societal expectations do individuals try to live up to, and which not? [15]

I conceive of the way in which modes of government interpellate subjects through specific programs as subjectification—the formation of positionalities and individual and collective identities.12) These interpellations constitute a link between discourses, dispositives, and practices. I argue that these normative/moral issues and the normative/moral expectations held by actors in a situation can be traced using mappings of the situation (CLARKE et al., 2018, pp.127ff.) and social worlds. In other words, by specifying "all the key individuals and social groups [... and] related social issues" (CLARKE & MONTINI, 1993, p.45), one can understand society as a whole and the social order it constitutes. I call this analytical procedure, in which single aspects of the larger picture are put together piece by piece, a mosaic mode. [16]

In the following section, I focus on ordered mappings of the situation and of social worlds/arenas following the idea of a bigger picture as developed by CLARKE et al. for situational analysis (2018, pp.127ff., 131ff.). I make a small modification to the ordered mappings of the situation, related to the above normative/moral issues and normative/moral expectations held by actors. In this way, I argue, researchers can use the modified ordered mappings and the mappings of social worlds/arenas to analyze the bigger picture. [17]

This part of the article shows by example how to analyze the situation in "mosaic mode." For this analysis, I take the Leap Across the Elbe as an epistemological break. This is not to be understood as a temporal limitation, but as a reference point for my analysis. First, I will explain how I modified the ordered mappings of the situation borrowed from situational analysis. I suggest a differentiation of the category "related discourses" so that these mappings can be used simultaneously with social worlds/arenas mappings. Afterwards, I will demonstrate very briefly how to analyze the bigger picture, based on my research in Wilhelmsburg, using the social worlds/arenas mappings in combination with the ordered mappings of the situation. [18]

4.1 Towards the bigger picture

In situational analysis, apart from the mappings of social worlds/arenas, CLARKE et al. suggested three more strategies: mappings of the situations, mappings of relations and mappings of positionality (2018, pp.127ff., 165ff.). Though the mappings of positionalities are suitable for analyzing the questions of specific subjectification or modes of subjectification (ALONSO-YANEZ, DE CASTELL & THUMLERT, 2022, pp.291f.), I will neglect them here.13) Instead, I will connect mappings of situations and social worlds/arenas. [19]

Following CLARKE et al. (2018), I suggest beginning to trace the pathways of power while mapping the situations. By analyzing the relationships between the elements of the situation and the relevant discourses, scientists can reflect on the underlying assumptions. In particular, using the ordered mappings of situations enables the researcher to identify the discourses and reorganizations of discourses that are relevant for the research interest (p.131; see also GAGNON, JACOB & HOLMES, 2015, p.275; TIETJE, forthcoming). Because of my particular interest in regulations and control, I emphasized the category of "related discourses" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.131) and looked into it thoroughly. I suggest extending this category and dividing it into "related discourses" and "discourses on normative/moral issues and normative expectations held by actors." Those aspects are already part of the mapping strategy developed by CLARKE et al. (ibid.), but I argue that the category becomes clearer when its relevance for the analysis is emphasized. In addition, I have kept the "related discourses" category for everything else (Table 1).14)

Table 1: Extended ordered situational mapping (based on my own data): Everyday life in the Wilhelmsburg neighborhood and activated civil society. Please click here to download the PDF file [20]

Table 1 is the ordered mapping of the situation of everyday life in Wilhelmsburg affected by an activated civil society (LESSENICH, 2013, p.16). While I started out with messy relational mappings of this situation, I choose to present this very neat, ordered mapping. As CLARKE et al. emphasized, ordered mappings are very useful to "be sure you have not overlooked or forgotten some relation" (2018, p.135). With the additional focus on normative and moral aspects of the situation, my thinking with the mapping allowed me to sharpen my analytical view of the human social entities and their actions, and to identify those relevant to my research interest. By focusing on the collective actors, researchers can identify the relevant social worlds. The number of tiles in the mosaic is higher than the number of geographical units of analysis suggested by Louis WIRTH (1938). Reconstructing the tiles in connection with the normative and moral issues and expectations can help hone the analysis. The question of "Who and what are in the broader situation?" (2018, p.134) that CLARKE et al. used to start their mappings, needs to be extended by also asking how: How do experiences come about and how is power constituted in the broader situation? Adele CLARKE emphasized that one "can look at social life as a constantly moving mosaic of social worlds, many overlapping. They constitute the porously-bounded structural organization of human commitments" (CLARKE & KELLER, 2014, §25). I argue for expanding this mosaic mode by including discourses on normative/moral issues and normative expectations held by actors. [21]

The interviewees in Wilhelmsburg, for example, emphasized the importance of voluntary work for the social participation of (racialized) people in the neighborhood. The members of this social world are interested in growing plants, harvesting vegetables and fruits, and having a good time in a less urban, more rural atmosphere near their living places. Founded as an idea by the authorities in charge of promoting the neighborhood's image15) a "garden was initially set up based on financing by the IBA and the IGS. They thought, in cooperation with two Wilhelmsburg institutions, that such a project would be a good idea" (interview Intercultural Garden, Hamburg, May 14, 2021), one member of the garden told me in an interview. The Intercultural Garden project was founded by external parties (external to the gardening group) as part of the plans to transform the neighborhood in the context of the internationally relevant IBA and IGS projects. The aims of the garden are practical lived international understanding and gardening that connects cultures.16) Acting self-dependently, but financed by local authorities, civil society organizes the social participation of racialized inhabitants in Wilhelmsburg. This is one of the flagship projects of Leap Across the Elbe, but it has developed its own independent structures and practices over time. Tracing this connection between the authorities and civil society, I took a closer look at the other collective actors and the social worlds related to or produced by them. Though I was not able to attend to every detail of the narratives in Table 1, the collective actors and normative/moral issues will be of further interest in the following section. [22]

4.2 Putting the pieces together

Based on the ordered mapping in Table 1, I started to analyze the social world of the Intercultural Garden. This piece of the mosaic is very close to the idea of a life-world or—echoing the words of Anselm STRAUSS (1978)—a classic social world constituted around one concern: gardening in an urban area. In the social world, drawing upon the term "intercultural" in its name, I identified some segmenting aspects and drew one—the little vegetable patches—in Figure 1. The vegetable patches are a core element of the social world: Some of the people are participating to "grow their own runner beans and spring onions" (interview Intercultural Garden, Hamburg, May 14, 2021) in the garden. Childcare is one segment in the social world. While the adults work on the patches, children play in the area, watched and accompanied by other adults. Some of them, though also members of the Intercultural Garden, do not work on vegetable patches, though it seems they enjoy the concept and the atmosphere of the urban garden.

Figure 1: Social world of the "Intercultural Garden." Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 1. [23]

Given that social worlds "can be families, disciplines, communities, organizations, you know, various kinds of hobby groups" (CLARKE & KELLER, 2014, §25), they allow the researcher to examine meaning-making procedures. As exemplified in Figure 1, scientists can gather that in relation to power, the segmentation of the social world goes hand in hand with a certain kind of segregation. The racialized members (so-called "Turkish migrants," "Portuguese migrants" and "Kurdish migrants") are more involved in the aspect of growing and harvesting than of having free time and playing with the children; occupations apparently more often undertaken by white students. Following the opportunities of social participation for racialized people, Figure 1 exhibits aspects of shared opportunities in the form of access to a gardening space in the neighborhood. The name, Intercultural Garden, leads to the assumption that it is an accessible space. At the same time, because of the necessity of labeling it that way, it can be read as a hint that the participation of racialized people is contested.17) [24]

In Figure 2, I mapped the social world of producing community spaces. This mapping shows the practices of collective actors intervening in the racialized exclusion from social participation. The feminist culture center called RIA or the Haus der Jugend (HDJ) [local youth center]—and many other bodies—produce spaces that are open to all the inhabitants of the neighborhood. Those spaces are co-constituted by the racialized inhabitants as well as by white inhabitants of Wilhelmsburg. Altogether, those social worlds constitute the social world of producing community space (Figure 2). [25]

In a study on governmentality, researchers were found to question the dualisms of free will and coercion or subjectivity and power and view them as one movement (LEMKE, 2008, p.43). Therefore, I re-examined the ordered mapping in Table 1. The moral/normative issues and expectations regarding "civil society's responsibility for social participation" are directly linked to the concept of the "migration society" (Table 1). The idea of being a migration society is contested in German debates on the ideas of democracy, integration and participation going hand in hand with racialized otherings and exclusion (STOCK, HODAIE, IMMERFALL & MENZ, 2022, pp.1ff.). Bearing in mind these conflicts related to the social worlds, I identified the migration society as one social arena in which the social worlds of my research interest are involved. I understand the social world Intercultural Garden as one of many tiles in the mosaic making up the bigger picture of social life (CLARKE & KELLER, 2014, §25). [26]

The Leap Across the Elbe caused a change in the people living in the neighborhood, which also went hand in hand with an increase in awareness of the district by the authorities and in public discourse. This led to better financial support for existing and newly founded participation projects, such as the Intercultural Garden. With this in mind, I started to analyze the relationships between the other collective actors (Table 1) and the Intercultural Garden. I followed the commitment(s) the members of a social world have, and the conflicts related to them.

Figure 2: Social world of "producing community spaces." Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 2. [27]

Thinking of Figure 1 and the social world of the Intercultural Garden, I identified a commitment by its members to both gardening itself and to making urban gardening accessible to all its members. The subworld of childcare within the social world of the Intercultural Garden points to the social dimension of participation. The social dimension is strongly connected to responsibility for others and—especially in the Intercultural Garden—characterized by a willingness to help each other. Childcare, for example, is important for giving all members of the social world enough time to tend to their vegetable patches. Caring is a very important factor in the social world, related firstly to the social world itself, secondly to the plants in the garden, thirdly to the patches, and fourthly to the members. [28]

Care work is often unpaid, which leads directly to the economic dimension of social participation. I concluded that it is interesting to focus on the practices of civil society that compensate for economic deficits. A lot of residents living in the Wilhelmsburg neighborhood have a low income, and aspects of the economic dimension are present in every other dimension of participation. There are several initiatives in the neighborhood trying to organize the long-term unemployed, provide food for homeless people or look after the local give-away.18) Some of them build the subworld of providing alternative basic care. Taken together, these civil society organizations constitute the social world of compensating for economic deficits (Figure 3). One aspect of support for the long-term unemployed is creating a space for meeting each other, getting to know one another or staying in contact, chatting about everyday troubles or how to deal with the employment agency. One of the main tasks of the self-organized initiative Wilhelmsburg in Solidarity is, for example, to deal with the demands of the employment agency and to advise each other about how to resist them.

Figure 3: Social arena of "migration society." Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 3. [29]

The arena of the migration society is constituted at the site where the different dimensions of social participation are negotiated. The intersecting social worlds and their concerns give insights into the way social participation is constituted and debated. As the "P" for participant in Figure 2 and Figure 3 shows, not every participant in the arena of the migration society is a member of every or even any social world. But there are of course also people who participate in different social worlds at the same time, and whose participation remains fluid (CLARKE, 1991, p.132). In my reconstructions of those practices of (granting) social participation, it became obvious that social participation is not necessarily produced by the state, either as a whole or in part; it can be created by civil society organizations, initiatives and individuals (TIETJE, 2021). [30]

These interventions to combat social inequality are connected to the power relations that exist in a society. While "social stratification and internal power relations between groups" (MBEMBE, 2001, p.44) are an obvious mode of governing people, neoliberal governance also takes place in the practices employed to support people or share privileges. Both social participation and the spaces producing it emphasize the relevance of civil society's practices and ideas about sharing privileges. Society's enactment of solidarity towards its members as a welfare state is reduced here, encouraging a welfare state transformation aimed at individualizing socialization. In neoliberal practice, individualization is imposed centrally, and is evident particularly in terms of activating citizens (LESSENICH, 2013, pp.16f.), which is meant to compensate for infrastructural deficits. The Intercultural Garden is one illustration of the idea that initiating projects of participation as part of urban transformation strategies refers to techniques of government. Those techniques combine the leading of people with the leading of oneself (BÜHRMANN, 2005, §1; FOUCAULT, 2005 [1994], pp.256f.). The Intercultural Garden project, to stay with this example, shows that communal funds for civil society projects are part of the activating strategy of neoliberal governance (FREIE UND HANSESTADT HAMBURG, BEHÖRDE FÜR WISSENSCHAFT, FORSCHUNG, GLEICHSTELLUNG UND BEZIRKE, 2021). [31]

Returning to the mosaic, in Wilhelmsburg, the changes happening in the context of the Leap Across the Elbe are quite obvious. Those processes are affecting social worlds, initiating shifts or enabling the constitution of new worlds. Not all of the shifts are positive, especially for the racialized residents. The appropriation of space by high income earners, or by white students who have moved into the area—with or without jute bags—also creates displacement and thus renewed exclusion.19) Thinking about how human commitment is organized, and about the interwoven analysis of the maps of situations and the maps of social worlds/arenas, enables the researcher to reconstruct the interconnections between discourses and practices. When reconstructing these interconnections, scientists can analyze the social order a society gives itself. Discourses are inscribed in subjects and subjects influence discourses through practices and knowledge production. [32]

For example, the concrete practices in the social worlds contradict the homogenizing designations that appear in the advertising quoted at the beginning. In contrast, citizenship laws, infrastructural deficits and racialized discourses create hierarchies in the residents' everyday lives. Those hierarchies limit their social mobility and opportunities for participation, making the authorities' sphere of control part of their everyday lives (MIGNOLO, 2010, p.93). Social participation intervenes in—or is an attempt to intervene in—this situation of inequality, in order to provide more opportunities for participation in society. The more options or practices exist, the more cohesive a society is. At the same time, practices of participation function as compensators for neoliberal politics (JAFFE & QUARK, 2006). Or, in other words, practices such as building social networks and social capital or forming solidarity and reducing wealth disparities are entangled with the procedures of establishing social order and regulation. [33]

In complex modern and postmodern societies, everything is flexible, fluid and on the move. Social worlds allow us to focus on moments of accordance. Researchers can use those moments to analyze the social order and regulations inherent in and organized by a society (BECKER, 1982, p.35). Researchers can focus on the formal procedures that social worlds follow and investigate the arenas where discourses enter society. By this means, researchers can conceptualize "society as a whole [...] as consisting of layered 'mosaics of social worlds' in arenas of shared concerns" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.148). By reconstructing those layered social worlds and analyzing them together with the mappings of situations—with a strong focus on moral and normative issues, the bigger picture can be pieced together in mosaic mode. This enables researchers to see how a society establishes social order and regulation, government, and governance—how a society understands itself. [34]

The short snippet from the advertisement in the beginning refers to an exclusionary, gendered and racialized understanding of people living in certain areas of the city. The administration of Hamburg came up with the idea of domesticating the "wild" Wilhelmsburg neighborhood—especially through social participation projects by the Leap Across the Elbe. The municipal funding of those projects works as if state responsibilities are being outsourced to civil society. While members may have different reasons for participating in the respective social worlds, their commitment seems to be related. Parts of civil society organize themselves to counteract the consequences of neoliberal practices in people's everyday lives. They do so, for instance, by jointly constituting a social world of gardening and opening sites where different dimensions of social participation overlap. The need for support is interwoven with the need that an activated civil society feels to be charitable and to take responsibility. [35]

I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and Sarah B. EVANS-JORDAN for their productive comments, and all the interviewees for letting me take part in their social worlds.

1) https://www.hamburg.de/stadtleben/4118118/die-wilde-13 [Accessed: March 27, 2023]; my translation. <back>

2) While in Germany a buggy is often read in a gendered way, vegetable sellers are often associated with Turkish immigrants and jute bags with the white middle class. <back>

3) For some reflections on research ethics see TIETJE (2023). <back>

4) The empirical insights presented here are preliminary results of my research on the regulation and control of the participation of migrants and racialized people. Although my research is not finished, the empirical examples are from of my preliminary results and can be read as part of my analytical process. <back>

5) "Leap Across the Elbe" is a planned transformation of the southern districts of Hamburg. The Elbe is the river dividing the north and south of the city, the south of Hamburg being the poorer and less developed part of the city. Wilhelmsburg is located on an island between two north and south arms of the river. <back>

6) In German statistics, a person is considered to have a background of migration if they themselves or one of their parents was not born in Germany. <back>

7) The SGB II regulates basic social security for job seekers and parts of the law on employment promotion in the Federal Republic of Germany. <back>

8) A small park in the neighborhood next to a river, the social center Honigfabrik, a primary school and a kindergarten. <back>

9) All interview excerpts used here have been translated by me. <back>

10) Situational analysis, because of its anti-dualistic background (CLARKE & MONTINI, 1993, p.44), is already particularly well-prepared methodologically for this kind of analysis, as I show elsewhere (TIETJE, forthcoming). <back>

11) Also, following conflicts is part of the analytical strategy of a situational analysis (POHLMANN, 2020, §52). <back>

12) On interpellation, see ALTHUSSER (1971 [1970], pp.180ff.). <back>

13) I follow up the opportunities of using those strategies in an analysis of governmentality elsewhere (TIETJE, forthcoming). <back>

14) Mappings are analytical tools and usually not for illustrating research, so the mappings used in this article are used only as an excerpt of the ongoing research. <back>

15) https://interkgarten.de/chronik.html [Accessed: March 27, 2023]. <back>

16) https://interkgarten.de/chronik.html [Accessed: March 27, 2023]. <back>

17) I will elaborate this elsewhere. <back>

18) https://www.hamburg.de/mitte/pressemitteilungen/15696708/neue-tauschbox-wilhelmsburg [Accessed: March 31, 2023]. <back>

19) https://www.listennotes.com/de/podcasts/parallel-dazu/15-wilhelmsburg-pJVMNY293XO [Accessed: March 27, 2023]. <back>

Alonso-Yanez, Gabriela; de Castell, Suzanne & Thumlert, Kurt (2022). Reflections on re-mapping integrative conservation: (Dis)coordinate participation in a biosphere reserve in Mexico. In Adele E. Clarke, Rachel Washburn & Carrie Friese (Eds.), Situational analysis in practice. Mapping relationalities across disciplines (2nd ed., pp.287-296). New York, NY: Routledge.

Althusser, Louis (1971 [1970]). Ideology and ideological state apparatuses (notes towards an investigation) (January-April 1969). In Louis Althusser (Ed.), Lenin and philosophy and other essays (pp.127-186). London: Monthly Review Press.

Becker, Howard S. (1982). Art worlds. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Boldt, Florian (2020). Hamburg-Statistik: In diesen Stadtteilen hat die Mehrheit Migrationshintergrund. Hamburger Morgenpost, October 26, https://www.mopo.de/hamburg/hamburg-statistik-in-diesen-stadtteilen-hat-die-mehrheit-migrationshintergrund-37538148 [Accessed: March 27, 2023].

Bührmann, Andrea D. (2005). The emerging of the entrepreneurial self and its current hegemony. Some basic reflections on how to analyze the formation and transformation of modern forms of subjectivity. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(1), Art. 16, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-6.1.518 [Accessed: January 5, 2023].

Butler, Judith P. (1993). Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of "sex". New York, NY: Routledge.

Chamberlain, Julie (2020). Experimenting on racialized neighborhoods: Internationale Bauausstellung Hamburg and the urban laboratory in Hamburg-Wilhelmsburg. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 38(4), 1-19.

Chamberlain, Julie (2022). Wilhelmsburg is our home! Racialized residents on urban development and social mix planning in a Hamburg neighbourhood. Bielefeld: transcript.

Clarke, Adele E. (1991). Social worlds/arenas theory as organizational theory. In David R. Maines (Ed.), Communication and social order. Social organization and social process: Essays in honor of Anselm Strauss (pp.119-158). New York, NY: de Gruyter.

Clarke, Adele E. (2003). Situational analyses: Grounded theory mapping after the postmodern turn. Symbolic Interaction, 26(4), 553-576.

Clarke, Adele E. & Keller, Reiner (2014). Engaging complexities: Working against simplification as an agenda for qualitative research today. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 15(2), Art. 1, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-15.2.2186 [Accessed: January 2, 2023].

Clarke, Adele & Montini, Theresa (1993). The many faces of RU486: Tales of situated knowledges and technological contestations. Science, Technology & Human Values, 18(1), 42-78.

Clarke, Adele E. & Star, Susan Leigh (2008). The social worlds framework: A theory/methods package. In Edward J. Hackett, Olga Amsterdamska, Michael Lynch & Judy Wajcman (Eds.), The handbook of science and technology studies (pp.113-138). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Clarke, Adele E.; Friese, Carrie & Washburn, Rachel (2018). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the interpretive turn (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dewey, John (1980 [1934]). Art as experience. New York, NY: Wideview/Perigee.

Dietze, Gabriele (2016). Das "Ereignis Köln". Feminina Politica, 1, 93-102.

El-Tayeb, Fatima (2016). Undeutsch: Die Konstruktion des Anderen in der postmigrantischen Gesellschaft. Bielefeld: transcript.

Ende, Michael (1990 [1960]). Jim Button and Luke the Engine Driver. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press.

Foucault, Michel (1992 [1990]). Was ist Kritik?. Berlin: Merve Verlag.

Foucault, Michel (2005 [1994]). Subjekt und Macht. In Daniel Defert, Francois Ewald & Jaques Lagrange (Eds.), Michel Foucault. Analytik der Macht (pp. 240-263). Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg, Behörde für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt (Hrsg.) (2005). Sprung über die Elbe: Hamburg auf dem Weg zur internationalen Bauausstellung – IBA Hamburg 2013, https://www.internationale-bauausstellung-hamburg.de/fileadmin/Die_IBA-Story_post2013/051030_sprung_ueber_die_elbe.pdf [Accessed: March 27, 2023].

Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg, Behörde für Wissenschaft, Forschung, Gleichstellung und Bezirke (Hrsg.) (2021). Hamburger Bürger:Innen-Beteiligungsbericht 2020, https://www.hamburg.de/contentblob/15316908/a48655081d7580bae601f05e445902ad/data/bericht-buerger-innenbeteiligung.pdf [Accessed: March 27, 2023].

Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg, Staatliche Pressestelle (Hrsg.) (2002). Leitbild: Metropole Hamburg – Wachsende Stadt. Hamburg: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg.

Gagnon, Marilou; Jacob, Jean D. & Holmes, Dave (2015). Governing through (in)security: A critical analysis of a fear-based public health campaign. In Adele E. Clarke, Carrie Friese & Rachel Washburn (Eds.), Social world: Vol. 1. Situational analysis in practice. Mapping research with grounded theory (pp.270-291). Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Hellweg, Uli (2007). World – city – spaces: Internationale Bauausstellung Hamburg. Hamburg: IBA Hamburg GmbH.

Hopf, Christel (2016). Schriften zu Methodologie und Methoden qualitativer Sozialforschung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

IBA Hamburg GmbH (2017). Wohnungsbauvorhaben der IBA Hamburg auf der Elbinsel Wilhelmsburg, https://www.hamburg.de/contentblob/9023936/0fb0d7cd11f157a1e67555713f944e80/data/iba-wohnungsbau.pdf [Accessed: March 27, 2023].

Institut für Bildungsmonitoring und Qualitätsentwicklung (2016). Bildungssituation: Elbinseln (Wilhelmsburg/Veddel). Lokale Bildungskonferenz, https://www.hamburg.de/contentblob/8217476/b70903395421e1b7b97aa052d0471c18/data/21-11-2016-vortrag.pdf [Accessed: March 27, 2023].

Jaffe, JoAnn & Quark, Amy A. (2006). Social cohesion, neoliberalism, and the entrepreneurial community in rural saskatchewan. American Behavioral Scientist, 50(2), 206-225.

Lembke, Judith (2017). Da traut ihr euch hin?. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, October 31, https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/wohnen/haus/wohnen-in-hamburg-wilhelmsburg-so-lebt-es-sich-im-viertel-15267860.html?printPagedArticle=true#pageIndex_2 [Accessed: March 27, 2023].

Lemke, Thomas (2002). Foucault, governmentality, and critique. Rethinking Marxism, 14(3), 49-64.

Lemke, Thomas (2008). Gouvernementalität und Biopolitik. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Lessenich, Stephan (2013). Die Neuerfindung des Sozialen: Der Sozialstaat im flexiblen Kapitalismus (3rd ed.). Bielefeld: transcript.

Luckmann, Benita (1970). The small worlds of modern man. Social Research, 37(4), 580-596.

Marttila, Tomas (2013). Whither governmentality research? A case study of the governmentalization of the entrepreneur in the French epistemological tradition. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(3), Art. 10, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-14.3.1877 [Accessed: January 5, 2023].

Mbembe, Achille (2001). On the postcolony. Studies on the history of society and culture: Vol. 41. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Mecheril, Paul (2016). Migrationspädagogik – ein Projekt. In Paul Mecheril (Ed.), Pädagogik. Handbuch Migrationspädagogik (pp.8-30). Weinheim: Beltz.

Mignolo, Walter (2010). Desobediencia epistémica: Retórica de la modernidad, lógica de la colonidad y gramática de la descolonialidad [Epistemic disobedience: The rhetoric of modernity, the logic of coloniality and the grammar of decoloniality]. Buenos Aires: Ediciones del Signo.

Ocejo, Richard E. (2013). Ethnography and the city: Readings on doing urban fieldwork. The metropolis and modern life. New York, NY: Routledge.

Offenberger, Ursula (2019). Anselm Strauss, Adele Clarke und die feministische Gretchenfrage. Zum Verhältnis von Grounded-Theory-Methodologie und Situationsanalyse. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(2), Art. 6, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.2.2997 [Accessed: January 1, 2023].

Pergande, Frank (2013). Durch sieben Welten in achtzig Gärten. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, April 27, https://www.faz.net/aktuell/gesellschaft/umwelt/internationale-gartenschau-durch-sieben-welten-in-achtzig-gaerten-12162404.html [Accessed: March 27, 2023].

Pohlmann, Angela (2020). Von Praktiken zu Situationen. Situative Aushandlung von sozialen Praktiken in einem schottischen Gemeindeprojekt, Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(3), Art. 4., https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.3.3330 [Accessed: January 5, 2023].

Sarasin, Philipp (2019). Foucaults Wende. In Oliver Marchart & Renate Martinsen (Eds.), Politologische Aufklärung – konstruktivistische Perspektiven. Foucault und das Politische. Transdisziplinäre Impulse für die politische Theorie der Gegenwart (pp.9-22). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Schaefer, Kerstin & Spengemann, Paul (Directors) (2013). Die Wilde 13 [Film]. Hamburg: Hirn und Wanst Produktion.

Schöne, Helmar (2003). Die teilnehmende Beobachtung als Datenerhebungsmethode in der Politikwissenschaft. Methodologische Reflexion und Werkstattbericht. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 4(2), Art. 20, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-4.2.720 [Accessed: March 31, 2023].

Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein (2019). Hamburger Stadtteil-Profile: Berichtsjahr 2018: Nord.regional. Hamburg: Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein.

Stock, Miriam; Hodaie, Nazli; Immerfall, Stefan & Menz, Margarete (2022). Arbeitstitel: Migrationsgesellschaft – Eine Einleitung. In Miriam Stock, Nazli Hodaie, Stefan Immerfall & Margarete Menz (Eds.), Arbeitstitel: Migrationsgesellschaft. Pädagogik – Profession – Praktik (pp.1-12). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Strauss, Anselm L. (1969 [1959]). Mirrors and masks: The search for identity. Norwich: Fletcher & Son Ltd.

Strauss, Anselm L. (1978). A social worlds perspective. In Norman K. Denzin (Ed.), Studies in symbolic interaction. An annual compilation of research (pp.119-128). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Strauss, Anselm L. (1993). Continual permutations of action. London: Taylor and Francis.

Strauss, Anselm L. & Corbin, Juliet M. (1996 [1990]). Grounded Theory: Grundlagen qualitativer Sozialforschung. Weinheim: Beltz, Psychologie Verlags Union.

Tietje, Olaf (2021). Soziale Teilhabe Geflüchteter und zivilgesellschaftliche Unterstützung: Engagement zwischen staatlicher Abschreckungspolitik und humanistischen Idealen. Voluntaris, 9(1), 10-24.

Tietje, Olaf (2022). Methodisch-kartographisch Veranderungen in der Forschung reflektieren: Cis-normative Perspektiven in der Geflüchtetenunterstützung nach dem "Sommer der Migration". In Irini Siouti, Tina Spies, Elisabeth Tuider, Hella von Unger & Erol Yildiz (Eds.), Othering in der Postmigrationsgesellschaft. Herausforderungen und Konsequenzen für die Forschungspraxis (pp.129-150). Bielefeld: transcript, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839463086-006 [Accessed: January 5, 2023].

Tietje, Olaf (2023). "You know now – talk about it!": Decolonial research perspectives and commissions of the research field. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 4, http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.3974 [Accessed: January 31, 2023].

Tietje, Olaf (forthcoming). Situational governmentality: Epistemologische und methodologische Überlegungen zu einer situierten Analyse von Regierungsweisen. In Leslie Gauditz, Anna-Lisa Klages, Stefanie Kruse, Eva Marr, Ana Mazur, Tamara Schwertel & Olaf Tietje (Eds.), Die Situationsanalyse als Forschungsprogramm. Theoretische Implikationen, Forschungspraxis und Anwendungsbeispiele. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Tuider, Elisabeth (2007). Diskursanalyse und Biographieforschung: Zum Wie und Warum von Subjektpositionierungen. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(2). Art. 6, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-8.2.249 [Accessed: March 27, 2023].

von Kalben, Theda (2018). Bildungsoffensive Elbinseln, https://www.nationale-stadtentwicklungspolitik.de/NSP/SharedDocs/Projekte/NSPProjekte/Soziale_Stadt/Bildungsoffensive_Elbinseln.html [Accessed: March 27, 2023].

Wirth, Louis (1938). Urbanism as a way of life. American Journal of Sociology, 44(1), 1-24.

Olaf TIETJE is a research associate at the Institute of Sociology at the LMU Munich. In his research he focuses on labor, gender studies, migration studies, social participation, and qualitative methods.

Contact:

Olaf Tietje

LMU Munich

Institute of Sociology

Konradstrasse 6, 80801 Munich, Germany

E-Mail: olaf.tietje@lmu.de

Tietje, Olaf (2023). Looking for the bigger picture. Analyzing governmentality in mosaic mode [35 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(2), Art. 19, https://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.2.4069.