Volume 24, No. 2, Art. 29 – May 2023

Mapping Transitions in the Life Course—An Exploration of Process Ontological Potentials and Limits of Situational Analysis

Karla Wazinski, Anna Wanka, Maya Kylén, Björn Slaug & Steven M. Schmidt

Abstract: In our article we focus on potentials and challenges that arise in the use of situational analysis for reflexive-relational transition research. We discuss how transitions can be mapped as transformation processes in the life course and mapping can function as reflective tool in research projects. We explore mapping transitions not only as static situations, but also in their complex processuality. To do this, we discuss transition and reflexive maps inspired by CLARKE's situational analysis, and thereby the challenge of mapping processes.

We start by discussing a mapping strategy inspired by situational analysis for the study of transitions, and proceed with an innovation of maps based on a research project. The aim is to trace the processes of change and to be able to analyze and map the connections between different dimensions and actors in these events. We reflect on various mapping strategies developed in the project to analyze spatial-material and temporal-processual aspects, their potentials, and limitations as well as the research process.

Mapping processes remains challenging and important for future research. Combining situational analysis and life course research opens up possibilities for researchers to better conceptualize the processuality of situations and to test different mapping procedures for this purpose.

Key words: situational analysis; transition research; relationality; reflexivity; practice theories, mapping

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Methodological Approach: Reflexivity in Mapping Transitions in the Life Course of People and Projects

3. Findings From and About the Mapping Process

3.1 Phase 1: Capturing processes in individual "transition maps"

3.2 Phase 2: Categorizing elements in individual "transition maps"

3.3 Phase 3: Visualizing life courses in final situational transition maps on "doing housing"

3.4 Phase 4: Presenting the processuality of life course transitions

4. Mapping Reflections About the Research Process

5. Discussion

In this paper, we approach life course transitions from a perspective of relational becoming (MEISSNER, 2019). While only a few researchers have used relational perspectives and process ontologies in life course research and gerontology so far (ANDREWS, SQUIRE & TAMBOUKOU, 2013), we argue that those perspectives and ontologies provide a fruitful angle from which to approach later life course transitions. On a general level, this means understanding social phenomena "as a complex and open-ended set of relations" (BRAIDOTTI, 2006, p.197). For the study of life course transitions, this implies shifting the common focus of life course research from the (transitioning) individual to the wider relational arrangement of transitioning as a practice, encompassing and arranging the different people (e.g., spouses, employers), discourses (e.g., active ageing), materialities (e.g., the body), and spatialities (e.g., the home), as well as other transitions. Transitions can thus be understood as practice processes that are linked between different elements and people (as acknowledged in the concept of "linked lives," ELDER, JOHNSON & CROSNOE, 2003, pp.13-14). In relational thinking, such processual arrangements are described with the Deleuzian notion of (in our case: transitional) assemblages (PHILLIPS, 2006). [1]

However, the centrality of time and temporality in transitions is what makes them a particular kind of social phenomena. Transitions are inherently processual—they are processes of change over time. So even though all social phenomena are temporal, the processual nature of life course transitions is what constitutes these phenomena as such. Although concepts of time are crucial in thinking about aging and the life course, they are often rather implicit in age studies, which mostly draw on chronological notions of time only (BAARS & VISSER, 2007). Here, the importance of a process ontology comes into play. [2]

Looking at the life course from such a perspective implies interpreting life stages and transitions between them as open-ended processes of becoming something and someone else. For example, when focusing on human actors, this could mean transitioning from a child to an adult; focusing on things, it could be transitioning from a single apartment to a family home; and focusing on discourses, the transition from a deficient to a resourceful image of aging could come into focus. In a transitional assemblage, all elements that, through their relations, form it become different with and through each other, through changes in their respective positionality and relationality. This means life course transitions, like retiring, do not necessarily follow a linear direction or pre-defined pathway but are socio-culturally, materially and historically contingent. They do not just happen naturally but emerge from and are enacted in social practices through which the social positions taken before, within, and after them are also shaped and constituted. Hence, in transitional assemblages, we always find dynamics that we can describe as intra-actions (BARAD, 2003)—that is, the entities (or what through them we come to perceive as such, like people or discourses) and the relations between them are made, shaped and changed by transitional practices from within instead of in-between (inter-actions). To put it simply: there is constant transformation being done in transitional assemblages. [3]

Hence, to apply a relational perspective of becoming to the study of life course transitions implies understanding them as open-ended processes of practices in which transformations of the elements involved in them—human and non-human, discursive and material—take place. These processes emerge, shift, and change their paths in transitional assemblages as the relationality between people; including, but not limited to, the transitioning individuals; discourses, bodies, spaces, things, other life courses, and transitions. [4]

Such a perspective of relational becoming implies certain methodological orientations and methods where not only actors (e.g., people) and elements (e.g., certain discourses), but the processual relations between them are emphasized. More recently, researchers have shown an increasing awareness for both relationalities and temporalities in methodologies (HANNKEN-ILLJES, 2007; SCHILLING & KÖNIG, 2020; STAMM, SCHMITZ, NORKUS & BAUR, 2020), and while situational analysis (SA) has become established as a fruitful tool for visualizing relationality (CLARKE, 2005, 2019; CLARKE, WASHBURN & FRIESE, 2022), when it comes to processuality, it has its limits. As Philipp KNOPP (2021) noted:

"When it comes to the issue of temporalities, I argue that SA's maps incorporate a primary focus on the situation as a time mode of concurrence and synchronicity. Its maps allow a simultaneous grasp of the situation of inquiry and help assemble constitutive elements and their complex relations (CLARKE & KELLER, 2014), but hinder the analysis of other time modes and the analysis of the step-by-step making of change, transitions, and processes" (§3). [5]

He further argued that "scholars need to reconsider the mapping techniques of SA as they dominantly depict the time mode of simultaneity" (§8). This has some advantages, as situations can be multi-sited and highly complex, and SA's maps still facilitate capturing them, quite literally, at a glance. Yet, it comes with the disadvantage of a certain degree of static or snapshot qualities of what is commonly defined as a situation in SA. [6]

We follow both KNOPP (2021) and Adele CLARKE and Rainer KELLER (2014) in stating that situations are defined in the research process itself and can hence also be characterized by transformation and change. KNOPP (2021) tried to tackle this issue by mobilizing the metaphor of photography for depicting a static construct of a situation and film-making for setting the situation in motion. He stated that "the main feature of this medium is that temporalities are broken up into frames and rearranged into a sequential order of images" (§14) and hence introduced the "flip map" (in reference to flip books). With this mapping technique, researchers can create a sequence of situational maps, put them in order and thus show processual qualities of change within a situation.

"Similar to an illustrated flip book for children, researchers can multiply synchronous slices by making a new map layer for every emerging element or event of the process under scrutiny. The many maps can be put on top of each other and ‘flipped' later on to form a stream of mapped moments. [...] This entails 1. the fragmentation of flows of practice by cutting and arranging sequences (disassembling), 2. the temporal synthesis or reconstruction, which turns the maps into meaningful processes (reassembling), and 3. several modes of sequencing, or changing speeds and directions of moving images while analytically watching the flip map as a processing and transforming whole" (§32). [7]

However, as helpful as this strategy might be for mapping certain processes, it only takes one step toward fully considering processuality. As KNOPP emphasized, a flip book is not a film, and flip maps are a sequence of flat maps rather than actually depicting dynamics in themselves. There seem to be two ways forward to bring processes into mapping methods. On the one hand, one could think of technological tools to animate such a sequence of situational maps, hence flipping them digitally and visually. On the other hand, one could turn back to life course research where we find quite a long tradition of visualizing (life course) time with the timeline (ELDER, 1975). Time-lining and related methods, like participatory diagramming (KESBY, 2000), are particularly widespread in childhood and youth transition research because it is assumed that these target groups might work better with visuals than language. For example, in the "Young Lives and Times" project, participants filled in timelines—usually simple lines with a beginning marked as "birth" and an end marked as the present—to capture biographical data, while also asking participants to map important world events (BAGNOLI, 2009). However, time-lining does not have to stop at the present; it may also be used to project the future. For the "Inventing adulthoods" project (THOMSON et al., 2002), lifeline charts were used as a tool to make young adults reason about their future at different points in time. Nancy WORTH (2011) developed the method of "life maps" to research youth transitions of visually impaired young adults. With life maps, she aimed to capture and visualize what she framed as "life course geographies [...] as a way to answer specific research questions about temporality that are more suited to a graphic method" (p.405). [8]

In some respects, timelines or life maps are similar to the SA's messy maps. That is, the broad collection and unsystematic depiction of elements within a situation in one map. However, such timelines and life maps are not entirely messy, meaning that the relations between elements are yet undefined. Instead, such mapping strategies require a certain temporal ordering from the very beginning—that is, arranging the elements (or life events) in the order that the timeline predefines. The main difference between these maps and maps created in a situational analysis is that in the former case the maps are usually created, or at least filled in, by the research participants themselves. By mapping their own lives, they, to some degree, take on the role of the researchers, reflecting about their own lives. Drawing on Davide NICOLINI's (2009) metaphor of "zooming in and zooming out" (p.1392), these mapping and reflection practices could then potentially be mapped again by situational analysis including both the maps, the mappers (us, the authors of the paper), and other elements (discourses, spaces, things) around them. Zooming out even further, such maps might also comprise the research team and its members themselves, who then must not only think about their positionality, but literally position themselves visually within the maps. This is in line with the main premises of a relational and reflexive transition research as well as CLARKE, FRIESE and WASHBURN's (2018) assumption that situations are always elastic. [9]

Hence, when we apply a relational and reflexive perspective of becoming to the study of life course transitions and thus conceptualize them as open-ended processes of transformation in an arrangement of practices and their elements, and when we aim to visualize and analyze these transitional assemblages reflexively in their relational becoming, we are confronted with a variety of methodological challenges. In this paper, we aim to explore the ways in which mapping techniques could be developed further to grasp not only the multi-perspectivity and complexity, but also the processuality of situations, both within the life course of a person and of a research project. We will begin with a description and reflection of our methodological approach (Section 2). After that, we will introduce and explain the different phases of developing our mapping technique (Section 3). Next, we will present how we used those maps as a tool to reflect on our research process (Section 4). This leads to a discussion of potentials and challenges of "transition maps" and "reflexive maps" (Section 5). [10]

2. Methodological Approach: Reflexivity in Mapping Transitions in the Life Course of People and Projects

To exemplify our methodological approach, we draw on data from the interdisciplinary project Perceived Housing and Life Transitions: Good Ageing-in Place (HoT Age) in which we focused on housing and life course transitions. The project is located at a Swedish and a German university and financed by a national funding body. It is a three-year international and inter-disciplinary project in which researchers from the fields and disciplines of gerontology, psychology, sociology, educational sciences, public health, occupational therapy, and of different career stages, from MA student to full professor, work together. Some of the involved researchers could draw on decades of joint collaborations, whereas others came anew to the research team. [11]

The funding body is financed by the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, and hence the fields of research they emphasize comprise health, working life, and welfare. The applicants created a project proposal at the intersection of their main areas of research—aging and place—and the funding body's main areas of research—health and welfare. In their previous and longstanding collaborations, some of the involved researchers had developed a concept to grasp the perception of home, a multi-dimensional construct derived and tested in mainly quantitative gerontological research which is used again as a framework for the "HoT Age" project. Perceived housing is a concept to grasp "issues of person-environment experience with relation to the socio-physical home environment" (OSWALD & KASPAR, 2012, p.75) and comprises a four-domain model including the domains of housing satisfaction, usability in the home, meaning of home and housing-related control beliefs (OSWALD et al., 2006). [12]

In the project, a mixed-methods design with an emphasis on quantitative analysis (CRESWELL & CLARK, 2017) was used, which was also reflected by the mainly quantitatively leaning research team. Most of the work should be carried out by the Swedish team, who thus managed most of the funding. The German team should complement with a qualitative focus group (FLICK, 2006) study to give depth to the quantitative results. With that in mind, the Swedish team hired a PhD student with quantitative expertise and the German team hired a research assistant on MA level with a qualitative background. However, early on, problems with access to the quantitative data set emerged, so it was decided to postpone the quantitative study, prioritize the qualitative study, and frame this as exploratory, instead of in-depth, until the quantitative data was available. At about the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic hit and was followed by the first lockdowns and contact restrictions in both countries putting the feasibility of in-person focus groups with a number of older adults—who were by then heavily framed as at-risk—into question. This challenge was discussed with the consensus to switch from focus groups to individual interviews—a method that was deemed less risky, even if carried out in person, and could also more easily be moved to telephone, or video communication tools. From the mostly psychological perspective of the project team, we collected interview data given the assumption that the perception of home and practices of housing can be expressed with language. [13]

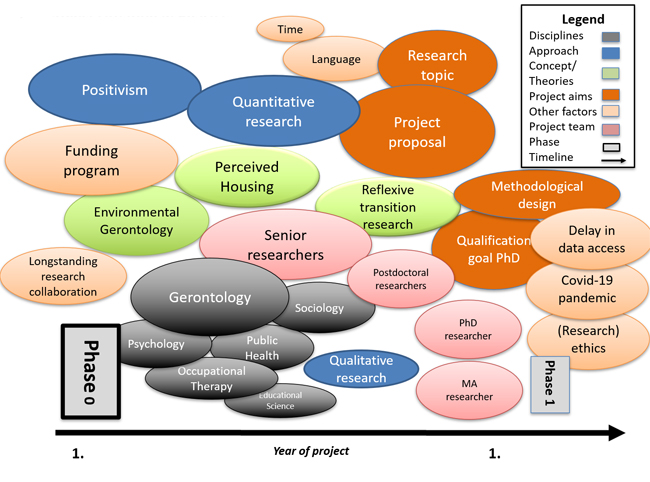

The call for participation, looking broadly for adults between 60 and 74 years old who wanted to talk about housing and had experienced at least one life transition in the past ten years, was distributed via pensioner organizations, snowballing, and a University of the Third Age. The response was surprising to the research team—about 100 persons were interested in being interviewed. Since the German team had less funding assigned, they followed a theoretical and iterative sampling strategy, deliberately looked for contrasting cases (e.g., persons with a different socioeconomic background, age, housing or who experienced other life course transitions)—resulting in 15 interviews. The Swedish team had a full-time PhD position assigned for this task and followed a purposeful sampling strategy, resulting in altogether 35 interviews (for a discussion of theoretical and purposeful sampling see COYNE, 1997). [14]

The problem-centered interview guide (WITZEL, 2000; WITZEL & REITER, 2012) was created as a joint endeavor in the research team, comprised of a narrative-biographical part in which persons were asked to narrate about the transitions they had experienced in the past ten years, and a more problem-centered part in which more specific questions about changes in the home, the neighborhood, and one's own health were posed. Data was collected between December 2020 and April 2021; most interviews were conducted via telephone or video communication tools like Zoom, and only a few were held in-person. All interviews were audio recorded and fully transcribed. They lasted from 48 minutes to 2 hours and 21 minutes with the mean of 1 hour and 26 minutes. [15]

Through the interviews, we gained rich in-depth insights into the complex relationships between a diversity of life course transitions and housing related perceptions. With this backdrop, the original plan to deploy content analysis (GRANEHEIM & LUNDMAN, 2004) was given up in favor of a more inductive and theory-generating approach orientated in constructivist grounded theory methodology (CHARMAZ, 2006) and situational analysis (CLARKE, 2005, 2019). [16]

To visualize and analyze transitional assemblages in their relational becoming, we followed CLARKE and colleagues' suggestion to use situational analysis as a flexible toolbox (2018, p.359) and configured the approach by combining it with mapping techniques from life course transition research. We combined elements from situational maps as introduced by CLARKE (2005) but mapped the elements in them not only in their relationality to each other, but also in relation to time—that is, on a timeline. [17]

3. Findings From and About the Mapping Process

3.1 Phase 1: Capturing processes in individual "transition maps"

In the first phase, we prepared the material for analysis using the software NVivo. In doing so, we coded the data applying a strategy suggested by the constructivist grounded theory according to Kathy CHARMAZ (2006). First, each event in the interviews was coded in an inductive way close to the material. Subsequently, focused codes were produced based on research interests, themes we identified in the data, and the theoretical framework of the project. Based on the research desideratum pursued in the project, we increasingly selected codes that encompassed the aspects of living experience, well-being, and health and continuously modified the selection of codes and dimensions of living that were made relevant in the interviews. [18]

After preparing the collected data, an individual map was created for each person interviewed. We used that strategy first because we were interested in the subjective perspective of the participants on housing, and it seemed necessary to stick close to the narration in the interviews. Second, we used elements in the maps which were highly abstracted versions of groups of codes from the interviews (see Phase 3 below) which appeared to be promising for use in the processual transition maps. Third, the maps, especially in their final version (see Phase 3), were created with code-based and non-code-based elements that were created by analyzing coded material. [19]

These first maps—"individual transition maps"—are thus visualizations of the narratives from the interviews in which the transitions that were reported were arranged along a timeline in the order of their occurrence and related to the aspects of housing, health, and other elements and actors that were made relevant. At this stage, the maps contained primarily focused codes. We used the program Microsoft PowerPoint for visualization. The aim of this procedure was to get an initial overview of the situation of the individual interviewees (the housing-related experience of transitions in the life course in recent years); to identify and trace relevant transitions, their accumulations, and sequences; and to display housing-related themes and processes of change that were reported in connection with various transitions. [20]

In this phase, it turned out that the interviews were very extensive and dense in information, which made it difficult to select all relevant codes for the limited size of the maps and to address our research question. Elements should primarily depict aspects of housing, but at the same time there should remain an openness to new themes and aspects in this situation. These questions were discussed in joint and regular analysis sessions, and the selection of the elements was iteratively modified. [21]

3.2 Phase 2: Categorizing elements in individual "transition maps"

In the second phase, the elements in the maps were categorized in joint analysis sessions as well and assigned to individual dimensions, which were marked in different colors in the maps. Categorizations were developed in an abductive process drawing both on the pre-existing sensitizing concepts described in the project proposal as well as coming from the empirical material itself. [22]

The individual elements in the transition maps were categorized and differentiated as follows. We used different colors to differentiate transitions and individual dimensions we identified. The category "transitions" was color-coded red, "health" was brown, and "housing" was green. We differentiated the "housing" dimension further with colored frames (e.g., neighborhood was color-coded green with an orange frame). The following dimensions of housing were of particular interest for our project: housing-related control beliefs, meaning, usability/accessibility, practices, social relations, neighborhood, proximity/mobility, safety/security, things/objects, economy/finance, and future plans. Given this background, elements that were assigned to this dimension were colored green and then divided into subcategories (e.g., "accessibility/usability"; "things/objects"). These subcategories were marked with a colored border around the green "housing" codes (e.g., the dimension "neighborhood" was colored green with an orange frame).

Figure 1: An example of a transition map for "Ida" in which the illness of the respondent's husband and the death of the husband

is shown. Categorized—and thus color-coded—elements were then arranged around these events chronologically. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 1. [23]

In Figure 1, an example of a transition map is shown. In this situation, for example, the interviewee states that she generally maintains a polite, distanced relationship with her neighbors ("trying to keep a nice, but distant relation to her neighbors," green squares with orange frame), but nevertheless has a closer relationship with a neighbor since her husband died ("having closer relationship to one neighbor since she lives alone"). These very preliminary findings from Ida's transition map suggest, for example, that experiencing the transitions "death of husband" seems also change "doing housing": before the death of her husband, Ida describes a very distant, although friendly, relationship with the neighborhood. The death of her husband, however, seems to change something in the sense that she seems to perceive the neighborhood in a different way and now maintains a close friendship with a neighbor after all. [24]

3.3 Phase 3: Visualizing life courses in final situational transition maps on "doing housing"

In the next step, we defined situations based on different transitional assemblages (e.g., retirement followed by immobility followed by relocation to a barrier-free flat). This procedure was based on the assumption that these different transitional assemblages go hand in hand with different changes in housing experience—i.e., it makes a difference whether a person moves before or after retirement. While we will focus on the methodological practices and challenges in this paper, you can read more about the findings of the study in Erik ERIKSSON et al. (2022). Given the quantity of codes in the initial transition maps, the aim of this procedure was to summarize the common features of codes to abstract code-based elements. These were then combined on this basis into two final situational maps. We chose two situations since most of the participants experienced the transitional assemblage of retirement and relocation in different chronological orders ("relocation before retirement" and "relocation after retirement"). In the final maps we depict the situation of all participants in our study who experienced the respective transitional assemblage. In terms of the research topic, "zooming out" from the single life course of the participants and housing-related dimensions to a broader life course perspective considering different transitional assemblages lead to an emphasis on the relational assumptions that underlie the reflexive transition research and practice theories once again and that can be visualized using CLARKE's situational analysis (2005, 2019). [25]

Based on the two situations, the thematic maps separated in the previous step and thus reduced to code-based elements, were merged again. The aim of this procedure was to give an overall view of a transition event and its housing-related changes, i.e., to work out the process of changes in the perception of home based on these transitional assemblages of relocations and retirement. At the same time, through our creation of the two final transition maps we aimed to enable a comparison of dimensions (e.g., accessibility/usability) of "doing housing" as a practice process between the two situations. Subsequently, the relations of the various transitional arrangements, actors, and practices were visualized by connecting related code and non-code-based elements with lines or by arranging them in spatial proximity to each other. This step of the mapping strategy resembles the reflection maps we will present later on (see Section 4).

Figure 2: Simplified final transition map of the situation "relocation after retirement" and the associated housing processes.

A timeline is presented on which the transitions "retirement" and "relocation" as well as the associated housing-related elements

(see legend) are arranged. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 2. [26]

In Figure 2, an example of the final transition map of the situation "relocation after retirement" and the associated housing changes is shown. In order to give an idea of these maps and the way they can be read, we present a simplified version of the final map that only includes a selection of dimensions (for full information on the final maps and findings of the study see ERIKSSON et al., 2022). The arrangement of the elements on the chronological timeline follows the temporal sequence of the process, as in the previous maps. The black lines between the dimension bubbles and element bubbles indicate relations between them. This figure allows the changes in different dimensions to be followed, e.g., the perception of the accessibility of the home, over time across different transitions. For example, this means that the needs in housing and the perception of its accessibility (e.g., in regard to its maintenance) change for interviewees in the process of experiencing the retirement transition, especially when experiencing it in assemblages of other transitions like illnesses. The change in the perception of the home and the retirement relates to the relocation-transitions because it prompts the decision for some to eventually adapt their housing to their changing needs regarding accessibility. These final maps were discussed in detail, modified, and reduced in the course of intersubjective analysis sessions in order to be able to formulate insights into particularly concise sections of the situation based on the very rich material and to work out the dimensions that would lend to a comparison of the situations. It should be noted that the single dimensions cannot be completely separated and are strongly related to each other—the separation is therefore only of an analytical nature, and that despite the focus on the two transitions "relocation" and "retirement," other transitions also influence the situation depending on the case. [27]

3.4 Phase 4: Presenting the processuality of life course transitions

Based on the interpretations of the two final transition maps from the interpretation groups, the findings were written down. On the one hand, the work of this phase revealed the challenges of doing justice to the claim and perspectivization of the theoretical and methodological approaches used in this study in writing. Using situational analysis for analyzing change in transitional assemblages poses the challenge of translating visualization into writing without losing the processuality, relationality, and complexity of "doing housing" that could be depicted in the maps. On the other hand, it displayed both the creative freedom one has in presenting the findings and how those different ways of presenting shape the way we think about the phenomenon we are researching. The transition maps with the elements placed along a timeline need to be read from left to the right. To capture the situation as a process would require writing down the findings in a chronological order, but how can it be done accordingly? To find the most adequate way to do so, we tried several variants of writing in this process. First, the final transition maps were each described individually and processes of change within each of the situations were traced in order to then look at them comparatively in a next step. However, this proved to be a very extensive form of writing, in which we found a large number of redundancies due to great similarities between the two final transition maps. So, as an alternative, we decided to compare the individual phases of the transition of both situations, i.e., the phase before the transition's relocation and retirement, then after retirement and finally after relocation. This allowed for a more precise comparison between the situations but made it more difficult to consider the complexity of such transition assemblages, which was the original aim of creating the transition maps. By writing them down in this way, the focus was rather on individual phases of these transitions, which should be avoided from the theoretical understanding of housing as a process of practice. The dynamic and non-static nature of housing was thus not conveyed. Finally, in a third alternative of writing, an attempt was nevertheless made to capture processes of change that occurred throughout the transitions. This third way of writing facilitated our thinking about these dimensions in a dynamic way within the transitional assemblages, without being repetitive or presenting the situation as a step-by-step process (again, for a detailed presentation of findings, see ERIKSSON et al., 2022). In the presentation of the results also the difficulty was shown of meeting the demand to capture complex co-constitutional relationships involving a wide variety of elements and actors. Although it was possible to think about and visualize these relations in the individual steps of the research process (e.g., the identification of discourses of "active aging" that come into play when talking about housing in old age), many of these elements and actors had to be neglected due to the high complexity of the dimensions of the living experience in the individual situations and their transitional assemblages. [28]

4. Mapping Reflections About the Research Process

Mapping life course transitions and thereby drawing on relational transition research and situational analysis requires reflexivity on the part of the researchers. As CLARKE and colleagues pointed out, researchers and research environment of a project significantly play into the mapping process and should hence be mapped as well:

"Another major methodological foundation and requisite for good SA research is quite serious researcher reflexivity [...] in SA, the researcher should write extensive memos about all these things, laying out any pertinent experiences, commitments or their absence vis-à-vis research issues, and how your own social positions may affect your perceptions of the research situation, of research participants, and participants' perceptions of you! Are you an outsider or an outsider within?" (2022, p.10) [29]

Through such reflexive mapping practices we were able to share insight into interdisciplinary projects like the one discussed in this paper. Our transition maps and the findings resulting from them were the result of an interdisciplinary process of questioning, negotiating, trial-and-error, and creative tinkering with methods which were informed by different theoretical and methodological backgrounds. Furthermore, our analysis process was shaped by power imbalances and hierarchies within the research team, funding structures, timelines and workloads, requirements for qualification theses, etc. Hence, we want to make the project situation explicit and our findings more transparent here. [30]

First of all, using SA as a methodological approach was agreed upon in the research process as a consequence of difficulties in the access to quantitative data and of therefore having more resources for the qualitative study than expected (see Section 2). SA appeared to be an innovative and accessible methodology without requiring reading long transcripts or speaking the same disciplinary language. Due to the visual appeal of maps, they were easy to decipher and understand, independent of how much preparation and knowledge one would have when joining an analysis session. Hence, SA seemed like a low-threshold way to engage everyone, both qualitative and quantitative, independent of time resources and discipline, in the data analysis process. [31]

In many ways, deploying SA in such a heterogeneous team proved to be fruitful for the project. For example, the way of thinking among part of the research team was very much centered on individual life histories and biographies and hence lead to the methodological innovation of transition maps in the first place. The choice to start with individual transition maps instead of cross-case situations was strongly influenced by the senior investigators' positioning in human-centered and individualist disciplines like psychology and gerontology. At other times, the use of SA proved challenging within the team. This became clear, for example, regarding the concept of "perceived housing." This concept was developed within the longstanding collaboration between parts of the quantitative Swedish and German research team and was operationalized in clearly defined dimensions and items, which shaped data collection and analysis. Some members of the research team appreciated the structuring function of such a concept. Others, however, felt like the concept was given too much place in the analysis by some team members, and would have wanted to keep their analytical gaze open longer. [32]

Against this backdrop, the two first authors of this paper felt the need to reflect upon the research process more systematically and started using processual maps as a reflection tool about the research process itself. Elements and actors of the research process were identified and mapped on a timeline that reflected the research process (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Map of the project "HoT Age." The first year of the project is shown on a timeline. The colorful bubbles are a collection

of different factors by which the project situation was defined, e.g., concepts or disciplines (see legend). Placement and

size of the bubbles refer to the relationship of those factors to each other and display their relevance in that project phase.

[33]

Zooming "in" and "out" in those maps enabled differentiated reflections on various aspects of the research process from specific research situations (like joint analysis sessions) to broader structural aspects like gender and class differences, hierarchy within the project team, constraints in resources (e.g., time and funding), or institutional settings (e.g., examinations and qualification reviews). Within the research process, such reflexive mapping can be useful for approaching difficulties as a basis for supervision and joint reflections within the project team. After the end of research, it may help to identify limitations and can also be helpful for making data re-useable for secondary analysis as well as detailing and contextualizing the origins of the data and findings. [34]

Finally, the process of reflexive mapping as carried out in this project must also be critically reflected on. Depending on who is involved, mapping will be conducted differently. In our case, the mapping was done by only two members of the research team and is thus strongly shaped by their positionality within the project. We had also had lively discussions with the team on the ethics of making this process transparent in a publication. In these discussions we covered the publication of confidential information from internal discussions, potential disagreements within the project team, and the fear of being portrayed in a manner that people concerned would disagree with (something we, as social scientists, often do much more light-heartedly with people we research about). However, due to these discussions, and even though there were only two of us from the team doing this reflexive step, we feel like we were able to reflect fairly on the research process. [35]

In this paper, we set out to bring life course transition research and situational analysis into a fruitful dialogue. We conceptualized life course transitions as open-ended processes of transformation in an arrangement of practices and their elements and aimed to visualize and analyze these transitional assemblages reflexively in their relational becoming. To do this, we discussed transition maps and reflexive maps inspired by Adele CLARKE's situational analysis (2005, 2019) and thereby the challenge of mapping processes of change. [36]

We aimed to explore the ways, in which mapping techniques could be developed to grasp not only the multi-perspectivity and complexity but also the processuality of situations both within the life course of a person (transition maps) and of a research project (reflexive maps). We did so by drawing on CLARKE's situational maps (ibid.) to not only visualize the relationality between elements within a situation but also the relationality of these elements to time. The challenge of accounting for processes in situations was already discussed in the debate around situational analysis and approached in different ways. This was done, for example, by KNOPP (2021), who, with a similar aim, invented "flip maps" to capture the dynamics of a situation. However, while acknowledging processuality explicitly, both CLARKE's and KNOPP's strategies still visualize snapshots in time and not processes per se. Hence, inspired by transition and life course research, we developed an alternative mapping approach in which elements of a situation or assemblage are ordered across a timeline. These transition maps, which can be read in a temporal sequence from left to right, are a useful tool for grasping transformation processes at a glance. [37]

In this endeavor, challenges were also revealed that result from the attempt to visually represent such multidimensional processual situations. The great complexity of life course transitions as understood from a perspective of reflexive-relational transition research ultimately required a significant simplification of the situation visualized in the mapping process and in translating the findings into writing. Trying out different techniques for mapping transitions, we saw that situational analysis mapping as currently devised still lacks ways of helping researchers to come to grips with sequences and accumulations of several transitions as well as several dimensions of housing experiences over time. It is thus central to consider how narrowly or broadly the boundaries of a "situation" are drawn and where agentic cuts (BARAD, 2003) are made in the research process. For example, in this paper our focus lay on two transitions, and the analysis was reduced to selected dimensions of the perception of home. However, the situation defined in this way always contained relations that seemed to reach beyond the limits we imposed, for example, when other transitions were strongly connected with the lived experience at the focused transitions of moving and retirement (e.g., illness, children moving out, changes in the partnership). These relations had to be cut at some point to cater to the complexity of portraying elements on a timeline. [38]

One of the main limitations of this study is the data that we mapped. SA, according to CLARKE (2005, 2019), was primarily developed for bringing together different data sources and to enable a multi-perspectival picture from these, which makes it particularly interesting for the research of transitions. However, our analysis of interviews did not take this approach to situational analysis but rather followed a primarily person-centered approach. As a next step, the mapping strategies we developed inspired by SA would have to be tried out and refined in other project contexts with multi-methodological research designs and possibly smaller data scope/density. [39]

In summary, we conclude that mapping processuality remains a challenge and an important field for future research and debate. While we addressed several questions in this paper, others still remain open—for example, how to account for both stability and change within a situation. Seeing situational analysis and life course transitions in dialogue with each other opens up possibilities for furthering discussions on how to grasp processes of change in situations and may encourage researchers to try out different mapping procedures. We hope that by trying out other mapping strategies proposed by CLARKE, such as social worlds/arenas maps and positional maps, further possibilities for mapping processuality can be developed. In general, the possibility to playfully develop SA and adapt it to one's own research phenomenon is promising, which makes it an attractive approach for life course and transition research in particular but also for other research fields. In our case, for example, it proved to be useful for reflexivity through mapping the research situation itself as a process, and our exploration might help to better grasp the complexity of the world methodologically—especially regarding time and temporality. [40]

Andrews, Molly; Squire, Corinne & Tamboukou, Maria (2013). Doing narrative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Baars, Jan & Visser, Henk (Eds.) (2007). Aging and time: Multidisciplinary perspectives. New York, NY: Baywood Publishing.

Bagnoli, Anna (2009). Beyond the standard interview: The use of graphic elicitation and arts-based methods. Qualitative Research, 9(5), 547-570.

Barad, Karen (2003). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs, 28(3), 801-831.

Braidotti, Rosi (2006). Posthuman, all too human: Towards a new process ontology. Theory, Culture & Society, 23(7-8), 197-208, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276406069232 [Accessed: April 25, 2023].

Charmaz, Kathy (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Clarke, Adele E. (2005). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Clarke, Adele E. (2019). Situating grounded theory and situational analysis in interpretive qualitative inquiry. In Adele E. Clarke, Rachel Washburn & Carrie Friese (Eds.), Situational analysis in practice: Mapping relationalities across disciplines (pp.22-49). London: Routledge.

Clarke, Adele E. & Keller, Rainer (2014). Engaging complexities: Working against simplification as an agenda for qualitative research today. Adele Clarke in conversation with Reiner Keller. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 15(2), Art. 1, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-15.2.2186 [Accessed: April 25, 2023].

Clarke, Adele E.; Friese, Carrie & Washburn, Rachel S. (2018). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the interpretative turn (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Clarke, Adele E.; Washburn, Rachel & Friese, Carrie (Eds.) (2022). Situational analysis in practice: Mapping relationalities across disciplines (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Coyne, Imelda T. (1997). Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries?. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(3). 623-630.

Creswell, John W. & Clark, Vicki L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Elder, Glenn H. (1975). Age differentiation and the life course. Annual Review of Sociology, 1, 165-190.

Elder, Glenn H.; Johnson, Monika K. & Crosnoe, Robert (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In Jeylan T. Mortimer & Michael J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course. Handbooks of sociology and social research (pp.3-19). Boston, MA: Springer.

Eriksson, Erik; Wazinski, Karla; Wanka, Anna; Kylén, Maya; Oswald, Frank; Slaug, Björn; Iwarsson, Susanne & Schmidt, Steven M. (2022). Perceived housing in relation to retirement and relocation: A qualitative interview study among older adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13314, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013314 [Accessed: April 25, 2023].

Flick, Uwe (2006). An introduction to qualitative research (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

Graneheim, Ulla H. & Lundman, Berit M. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105-112.

Hannken-Illjes, Kati (2007). Temporalities and materialities. Introduction to the thematic issue on time and discourse. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(1), Art.1, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-8.1.199 [Accessed: April 25, 2023].

Kesby, Mike (2000). Participatory diagramming: Deploying qualitative methods through an action research epistemology. Area, 32(4), 423-435.

Knopp, Philipp (2021). Mapping temporalities and processes with situational analysis: Methodological issues and advances. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 22(3), Art.17, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.3.3661 [Accessed: April 25, 2023].

Meissner, Kerstin (2019). Relational Becoming – mit Anderen werden. Soziale Zugehörigkeit als Prozess. Bielefeld: transcript.

Nicolini, Davide (2009). Zooming in and out: Studying practices by switching theoretical lenses and trailing connections. Organization Studies, 30(12), 1391-1418.

Oswald, Frank & Kaspar, Roman (2012). On the quantitative assessment of perceived housing in later life. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 26(1-3), 72-93.

Oswald, Frank; Schilling, Oliver K.; Wahl, Hans-Werner; Fänge, Agneta; Sixsmith, Judith & Iwarsson, Susanne (2006). Homeward bound: Introducing a four domain model of perceived housing in very old age. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 26(3), 187-201.

Phillips, John (2006). Agencement/assemblage. Theory, Culture & Society, 23(2-3), 108-109.

Schilling, Elisabeth & König, Alexandra (2020). Challenging times. Methods and methodological approaches to qualitative research on time. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(2), Art.1, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.2.3508 [Accessed: April 25, 2023].

Stamm, Isabell; Schmitz, Andreas; Norkus, Maria & Baur, Nina (2020). Process‐oriented analysis. Canadian Review of Sociology, 57(2), 243-246.

Thomson, Rachel; Bell, Robert; Holland, Janet; Henderson, Sheila; McGrellis, Sheena & Sharpe, Sue (2002). Critical moments: Choice, chance and opportunity in young people's narratives of transition. Sociology, 36(2), 335-354.

Witzel, Andreas (2000). The problem-centered interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(1), Art. 22, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.1.1132 [Accessed: May 7, 2023].

Witzel, Andreas & Reiter, Herwig (2012). The problem-centred interview. London: Sage.

Worth, Nancy (2011). Evaluating life maps as a versatile method for lifecourse geographies. Area, 43(4), 405-412.

Karla WAZINSKI studied social work/social pedagogy in Koblenz and educational science at Goethe University Frankfurt/M. Afterwards, she worked as a research assistant in various research projects in the Department of Educational Science at Goethe University Frankfurt. Since 2022, she is a doctoral candidate in the Emmy Noether group Linking Ages––The Material-Discursive Practices of the Un/Doing Across the Life Course, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) [German Research Foundation]. Her expertise and research interests include qualitative social research, in particular situational analysis, housing and (housing) transitions as well as un/doing of age and the construction of age boundaries in the life course.

Contact:

Karla Wazinski

Goethe University

Faculty of Educational Science

Theodor-W-Adorno-Platz 6

60323 Frankfurt/M., Germany

Tel.: +49 (0)69 79836411

E-mail: wazinski@em.uni-frankfurt.de

URL: https://www.uni-frankfurt.de/129357041/Karla_Wazinski

Anna WANKA studied sociology and law at University of Vienna, where she finished her PhD in sociology in 2016. From 2009 to 2016 she worked as a junior researcher in the research group "Family, Generations, Life Course, and Health" at the Department of Sociology in Vienna. Between 2017 and 2021 she was a postdoctoral researcher in the DFG-funded interdisciplinary research training group "Doing Transitions" at Goethe University Frankfurt/M., where she is now part of the consortium. In this group she worked on the project "Doing Retiring—The Social Practices of Transiting into Retirement and the Distribution of Transitional Risks" and contributed to the establishment of a broader practice-theoretical framework on transitions from childhood to later life. Between 2020 and 2021 she additionally held a postdoctoral position on mixed-methods research at University of Stuttgart. Between 2021 and 2022 she was a deputy professor of political sociology of social inequalities at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. Starting in 2022, she is leader of DFG-funded Emmy Noether research group Linking Ages––The Material-Discursive Practices of the Un/Doing Across the Life Course, funded by DFG. Her areas of expertise comprise the social practices of "un/doing age," life course transitions / retirement and the re/production of social inequalities across the life course, aging and technologies, age-friendly cities and communities, aging migrants, and lifelong learning. Theoretically she is specialized in practice theories, in which she was trained in the postgraduate program "Sociology of Social Practices," as well as through several international research fellowships. She is competent in both qualitative and quantitative methods and has high expertise in mixed-methods research.

Contact:

Dr. Anna Wanka

Goethe University

Faculty of Educational Science

Theodor-W-Adorno-Platz 6

60323 Frankfurt/M., Germany

Tel.: +49 (0)69 79836782

E-mail: wanka@em.uni-frankfurt.de

URL: https://www.uni-frankfurt.de/129313223/Anna_Wanka

Maya KYLÉN, PhD in medical health science, specializing in gerontology, is a researcher at Lund University, Sweden. She belongs to the "Applied Gerontology Research Group," affiliated to the Center for Ageing and Supportive Environments (CASE). She is also affiliated to the research group Environment, Technology and Participation at Dalarna University. Her research interests include integrated care, housing, health, and well-being among older adults. She is involved in several national and international interdisciplinary research projects focusing on late life transitions, how economic aspects influence housing choices and relocation patterns in older age, and how the built and social environment can be supported by a person-centered rehabilitation process at home among people with stroke.

Contact:

Maya Kylén, PhD

Lund University

Department of Health Science

Sölvegatan 19

22100 Lund, Sweden

Tel.: +46 (0)46 2221838

E-mail: maya.kylen@med.lu.se

URL: https://portal.research.lu.se/en/persons/maya-kyl%C3%A9n/fingerprints/

Björn SLAUG is associate professor in health sciences at the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University. He is a member of the research group "Active and Healthy Ageing," affiliated to the Centre for Ageing and Supportive Environments (CASE=. In his research he focuses on the built environment and how it can be designed or adapted to support active and healthy aging. He has a background in public health research and has extensive experience from methodological research, particularly concerning person-environment fit issues. He is currently involved in several national and international research projects related to the relationships between the built environment and different aspects of health, often from a public health perspective.

Contact:

Björn Slaug, PhD

Lund University

Department of Health Science

Sölvegatan 19

22100 Lund, Sweden

Tel.: +46 (0)46 2221838

E-mail: bjorn.slaug@med.lu.se

URL: https://portal.research.lu.se/en/persons/bj%C3%B6rn-slaug

Steven M. SCHMIDT is associate professor of medical psychology at the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University. He leads the "Applied Gerontology Research Group" and is the coordinator for the Centre for Ageing and Supportive Environments (CASE). In his research he focuses on the relationships among the environment, health/function, and psychosocial factors in the aging population. He predominantly takes a public health approach in collaboration with inter- and trans-disciplinary teams. To increase the relevance and impact of research findings, most projects include active user involvement (e.g., government agencies, policy makers, industry, older people).

Contact:

Steven M. Schmidt, PhD

Lund University

Department of Health Science

Sölvegatan 19

22100 Lund, Sweden

Tel.: +46 (0)46 2221983

E-mail: steven.schmidt@med.lu.se

URL: https://portal.research.lu.se/en/persons/steven-schmidt

Wazinski, Karla; Wanka, Anna; Kylén, Maya, Slaug, Björn & Schmidt, Steven M. (2023). Mapping transitions in the life course—An exploration of process pntological potentials and limits of situational analysis [40 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(2), Art. 29, https://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.2.4088.