Volume 24, No. 2, Art. 28 – May 2023

Children and Implicated Actors Within Social Worlds/Arenas Maps: Reconsidering Situational Analysis From a Childhood Studies Perspective

Nicoletta Eunicke, Jana Mikats & Claudia Glotz

Abstract: We discuss situational analysis as an auspicious method for researchers in childhood studies due to its critical-reflexive approach towards power relations, marginalization, and relationalities of collective action—which are topical issues within childhood studies. Especially the position of "implicated actors" (CLARKE & MONTINI, 1993, p.45), a key concept of social worlds/arenas theory, seems conducive towards research about children. However, we also raise concerns about potentially re-marginalizing children in and through research when it is assumed that, as implicated actors, they are not involved in social worlds/arenas and therefore also not involved in social action. We discuss the methodological potentials and pitfalls of social worlds/arenas maps and the use of the concept of implicated actors to analyze children and childhood. We draw from empirical projects and central conceptual debates within childhood studies and focus on three theses: With social worlds/arenas maps 1. researchers are at risk of rendering children invisible; 2. researchers cannot (yet) capture the intragenerational relations of children (as implicated actors); 3. researchers cannot fully account for a relational understanding of children and childhood. Based on these considerations, we suggest how to enable and reconsider the analysis of children and childhood with social worlds/arenas maps using situational analysis.

Key words: social worlds/arenas maps; situational analysis; implicated actors; childhood studies; generational order; generational relations; child; family; school; home-school relations

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Social Worlds/Arenas Theory and Mapping in SA

3. Experiences With Social Worlds/Arenas Maps for Research on Children and Childhood

3.1 Thesis 1: Researchers are at risk of rendering children invisible

3.1.1 Background of the project: The order of the family in home-school relations

3.1.2 Empirical illustration: Looking out for children with a social worlds/arena map

3.2 Thesis 2: Researchers cannot (yet) capture the intragenerational relations of children (as implicated actors)

3.2.1 Background of the project: The concept of dialogical learning in everyday school life

3.2.2 Empirical illustration: Children's actions from an intragenerational perspective

3.3 Thesis 3: Researchers cannot fully account for a relational understanding of children and childhood

3.3.1 Background of the project: Organizing family life in relation to home-based working

3.3.2 Empirical illustration: Grasping multidimensional involvements of children (and childhood)

4. Conclusion

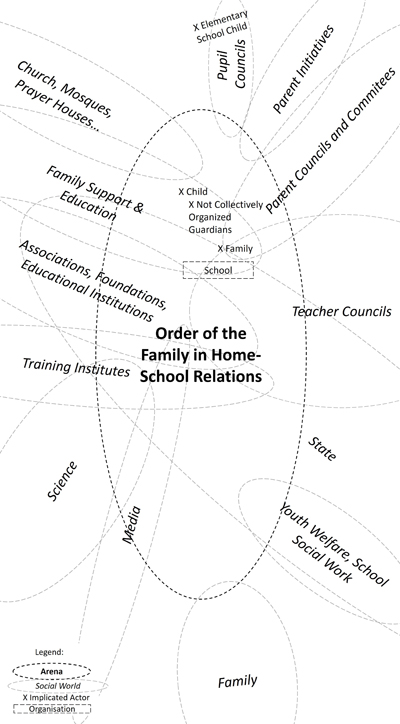

Since the publication of Adele E. CLARKE's monograph "Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory After the Postmodern Turn" (2005), a growing number of researchers have shown interest in this "theory/methods package" (CLARKE & STAR, 2008, p.117). As researchers have integrated situational analysis (SA) into different methodological traditions and in new disciplines and fields, a lively discussion about its methodological potentials and limits has ensued (e.g., DIAZ-BONE, 2013; GAUDITZ et al., 2023; MATHAR, 2008; WHISKER, 2018). Due to the range of integrated theoretical traditions in the methodology of SA, researchers in different fields were attracted to this method. However, because of this theoretical variety, researchers must thoughtfully adapt SA analytical approaches to the researched phenomenon and reconcile them with the discipline's specific key concepts. We begin our discussion of SA with this hurdle in mind and with particular attention paid to social worlds/arenas maps—one of four types of maps in SA (CLARKE, FRIESE & WASHBURN, 2018)—from a childhood studies perspective. [1]

Childhood studies is a diverse and interdisciplinary research field. Researchers in the field are concerned with various aspects of children's lives and their positions as children in society as well as the understanding and social construction of the child and childhood (for an overview see BÜHLER-NIEDERBERGER, 2020 [2011]; CANOSA & GRAHAM, 2020; PUNCH, 2020; QVORTRUP, CORSARO & HONIG, 2009). The social position of children is structured by the generational order, which is "a complex set of social processes through which people become (and are constructed as) 'children' while other people become (and are constructed as) 'adults'" (ALANEN, 2001, pp.20f.). We identify SA as an auspicious method for researchers in childhood studies because of the critical and reflexive approach toward power relations and marginalization with roots in feminist research (EUNICKE & MIKATS, 2023; OFFENBERGER, 2019). [2]

As researchers in the field of childhood studies, we feel the attractiveness of the social worlds/arenas approach lies in its versatility as a methodological tool to examine collective commitments, relations, arenas of action, and controversies and debates. This versatility is particularly appealing because we study children and childhood from a generational perspective in three different domains: home-school relations, schools, and families (see Section 2). CLARKE (1991) specified that with a social worlds/arenas approach, researchers would focus "on collective actors of many types including but not limited to formal organizations" (p.129). However, the theoretical anchoring of collective action in social worlds/arenas might become one of the central challenges for understanding the situatedness of children as social actors who often cannot be considered as collectively organized groups. Following the postcolonial researcher Gayatri C. SPIVAK (1988), Manfred LIEBEL (2020)—a children's rights researcher—pointed out that children were subalterns who remained unheard and lived frequently under conditions that prevented them from organizing themselves in collectivities: "This is not because the subalterns cannot speak, but because their speech is not given prominence in hegemonic discourse" (p.111)1). In social worlds/arenas maps, this lack of collective organization indicates that actors are implicated, which means that they are "silenced or only discursively present" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.76) and thus not considered to be participating in social worlds/arenas: "Neither kind of implicated actor is actively involved in the actual negotiations of self-representation in the social world or arena, nor are their thoughts or opinions or identities explored or sought out by other actors" (CLARKE & STAR, 2008, p.119). [3]

Especially from the perspective of childhood studies, it is remarkable that CLARKE et al. (2018) have included the position of implicated actors in the SA methodology and, in doing so, opened the door to look at "the situatedness of less powerful actors in the situation and the consequences of others' action for them" (p.76). Despite SA not (yet) being an established method in childhood research, those researchers already established with using SA have already validated positioning children as implicated actors in their maps (e.g., GRUNAU, 2021; MARR, 2020; VIVIANI, 2016). In this article, we raise concerns of re-marginalizing children in and through research, when researchers conceptualize them as implicated actors, and, in doing so, assume that children are not involved in "social action" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.150, emphasis added). [4]

In this contribution, we share our experiences of working with social worlds/arenas maps as a tool within the scope of three empirical projects with and about children and childhood. In these qualitative multi-method and multi-site research projects, we focused on children whom we studied in home-school relations (EUNICKE, Section 3.1), in schools (GLOTZ, Section 3.2), and in families (MIKATS, Section 3.3). We started the methodological and conceptual discussion presented in this article by asking all three authors the same question in their respective research projects: Why do we struggle to appropriately conceptualize children with social worlds/arenas maps, despite the seemingly perfect fit between SA and childhood studies? With this article, we thus aim to discuss the potentials and pitfalls of using the concept of implicated actors within social worlds/arenas maps for the analysis of children and childhood. In doing so, we provide a methodological contribution to SA and especially to social worlds/arenas maps from a childhood studies perspective. [5]

We begin the article by presenting social worlds/arenas theory and mapping and then introduce the concept of implicated actors in greater detail (Section 2). In the presentations of three central theses, we draw from our empirical work and core concepts of childhood studies (Section 3). Ultimately, based on these considerations, we suggest whether and how to approach children as implicated actors in social worlds/arenas maps, and thus facilitate reconsideration of SA from a childhood studies perspective (Section 4). [6]

2. Social Worlds/Arenas Theory and Mapping in SA

Two central promises are connected to the methodological concept of social worlds and arenas as introduced by CLARKE (2005): to become more absorbed by the situation and to obtain a better overview of collectives and "sites of action" (p.86) with a "birds eye view" (MATHAR, 2008, §23). CLARKE et al. (2018) claimed that this "big-picture analysis of social action" was "rarely done in qualitative inquiry" (p.150). In doing so, they addressed trends in qualitative research in which researchers focused on individuals and did not include social action by "aware and committed collectivities" (ibid.). [7]

The development of social worlds theory can be illustrated as a journey from territorial to professional to discursive conceptualizations. Ideas on social worlds can be traced back to studies of the Hull House movement (GRUENBERGKOLLEKTIV, 2020) and the Chicago School. In this era, researchers drew from maps of social worlds to focus on social as well as territorial or geographical spaces. In symbolic interactionism, an increasing de-territorialization of the concept of social worlds began (SCHÜTZE, 2016). Social worlds were used and revised to analyze professional work. To accomplish this, researchers incorporated a professional organizational framework and focused the concept on the interactions of collective (and adult) actors in their professions and the relations between different social worlds (ibid.). However, CLARKE et al. (2018) criticized this approach of centering the view on powerful collective actors and disregarding less powerful or silent actors. Ultimately, CLARKE et al. modified the understanding of social worlds/arenas to overcome the formerly narrow associations of social worlds with territorial boundaries, professions, organizations, and the function of action. [8]

To integrate notions of power and marginalization, CLARKE et al. turned to relational perspectives, collective action, and extended social worlds/arenas with a post-structural, discourse-analytic orientation. They defined social worlds as "meaning making worlds that organize people's commitment to action" (CLARKE & KELLER, 2014, §25). Based on these commitments, people's lives are shaped by various collectives, such as family, (professional) disciplines, organizations, or leisure groups (ibid.)—places where consent and interpretive authority are contested. Different representatives of social worlds meet and negotiate central issues in arenas: "An arena happens where multiple worlds intersect, where their interests intersect" (§36). In this respect, arenas are places of dispute: "sites of negotiations" and "discursive sites" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.73). Tom MATHAR (2008) argued that the main difference between social worlds and arenas would be their size. Alternatively, CLARKE et al. (2018) stressed that there is a difference in the fluidity of social worlds and arenas; the latter usually stays longer, while the others come and go and are re-constructed in arenas. Still, this fluidity of social worlds should not be understood as accidental: In an interview with Reiner KELLER (2014) about SA and the concept of social worlds, CLARKE answered the question, "It's not just people lingering together in the same place" with an emphatic, "No, no, not at all" (§29). Later, CLARKE elaborated by using the example of a park:

"Anybody can stop and watch the skating but there are regulars who come to skate all the time, so they form a social world. They know about skating in the park—they are the 'insiders' of that world while the observers are outsiders looking in—unless they become regulars!! Change their positions!" (§32). [9]

Social worlds and their subworlds can be informal or organizational. Individuals can move between these social worlds. However, it is vital that researchers do not view these worlds as sites of "singular acts of individual action" (STRÜBING, 2021 [2004], p.120), but rather as sites of collective commitments. In the development of the mapping strategies for SA, CLARKE et al. (2018) thus drew on social worlds/arenas theory to facilitate the analysis of sites of collective commitment and action. In doing so, they introduced a conceptual toolbox with "sensitizing concepts to help in creating and especially in analyzing social worlds/arenas maps" (p.149). Implicated actors/actants are one of these concepts with which researchers turn to (power) relations and relationships in social worlds and arenas or the situation in general (CLARKE & MONTINI, 1993; CLARKE & STAR, 2008). The position of implicated actors is characterized by a lack of self-representation and/or active participation in social worlds/arenas (CLARKE et al., 2018). Accordingly, with the concept of implicated actors, researchers explicitly focus not only on collective action, but also on actors/actants who are not organized in social worlds. They are represented on social worlds/arenas maps as "atomized–i.e., there is no collective social action" (MATHAR, 2008, §24). Although implicated actors are not collective social actors, the actions in the arenas nevertheless have consequences for them (CLARKE et al., 2018). Moreover, other actors negotiate and define what implicated actors are, think or need, mostly to advance their own interests and concerns, and not those of implicated actors (ibid.). [10]

For the creation of social worlds/arenas maps, CLARKE et al. proposed several questions that accompany the mapping process by writing memos. These questions—that should be answered for every single social world and every arena on a map—range from questions concerning the work and commitment of the social world at hand, the internal and external definitions of social worlds, technologies, significant discourse topics, as well as the question regarding which additional data should be collected (ibid.). With these questions, CLARKE et al. emphasized that mapping is part of an analytical process, and the maps (like all the other maps of SA) are thus work-in-progress maps. Working with them should provoke new thoughts and perspectives on the situation, which we now demonstrate with our experiences of social worlds/arenas mapping from a childhood studies perspective. [11]

3. Experiences With Social Worlds/Arenas Maps for Research on Children and Childhood

In our work with social worlds/arenas maps, we were driven by the idea that these maps are "especially useful in analyzing the different perspectives and positions of different worlds on key issues and seeing power in action in arenas" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.148). This is an idea that we see reflected in ongoing debates—on a theoretical but also on a methodological level—in the field of childhood studies, in which researchers critique and aim to overcome a generalized figure of "the individualized monadic child which carries or holds agency unto itself" (SPYROU, ROSEN & COOK, 2018, p.4). Thus, the baseline for our discussion and reflection on social worlds/arenas maps from a childhood studies perspective is the following question: "How are the child, children, childhood constituted by, and involved in the constitution of" (p.13) the situation? [12]

With empirical examples of our projects, we underline that our methodological considerations are grounded in the specific situation and thus in the constitution of the child, children, and childhood in home-school relations, schools, and families from a generational perspective. In SA, as a theory/methods package, researchers must not use the method as a servant of their theoretical assumptions but ground these theoretical assumptions empirically (CLARKE, 2005). Therefore, with each of the following three theses, we address a topical issue in childhood studies and illustrate the match with SA's analytical approaches. We discuss the theses by first looking at the broader map and then by zooming in on implicated actors' positioning within the map.

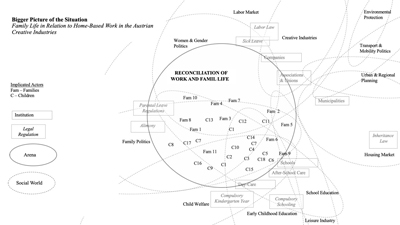

By combining the institutionalization of childhood with the organizational focus of social worlds/arenas maps, researchers are at risk of rendering children invisible (Section 3.1).

By reconstructing children as implicated actors in social worlds/arenas maps, researchers cannot (yet) capture the intragenerational relations of children (as implicated actors) (Section 3.2).

By conceptualizing children as implicated actors in social worlds/arenas maps, researchers cannot account for a relational understanding of children and childhood because their insights remain (still) too one-dimensional (Section 3.3). [13]

By presenting these three theses, we investigate the potentials and pitfalls of using the concept of implicated actors within social worlds/arenas maps to analyze children and childhood. Firstly, we start each section by embedding the thesis in theoretical discussions within childhood studies and elaborating on how we reconciled these concepts with the theoretical foundation of SA, particularly using the social worlds/arenas theory. Secondly, we introduce the background of each project, with which we, thirdly, illustrate the thesis empirically. [14]

3.1 Thesis 1: Researchers are at risk of rendering children invisible

Cindi KATZ (2008) conceptualized childhood as a spectacle because representatives of multiple social worlds invest in childhood to provide security for current and future economically uncertain times: "[C]hildren are a bulwark against ontological insecurity and other anxieties about the future" (pp.9f.). They pointed out the ambivalence of modern childhoods: While in a neoliberal era, the social wage has been increasingly privatized, "the investment in children [...] seems more collectivized than in earlier periods" (ibid.). Researchers in childhood studies have called this collectivization the institutionalization of childhood (e.g., BOLLIG, NEUMANN, BETZ & JOOS, 2018; ZEIHER, 2009). [15]

Two different understandings of institutionalization can be found. Firstly, researchers use the term to describe that children spend more time in (formal) institutions like school or kindergarten and less time "freely in the outdoor urban and rural space" (HOLLOWAY & PIMLOTT-WILSON, 2014, p.623). With this most common understanding of institutionalization, researchers can address the institutions of childhood (ESSER & SCHRÖER, 2019). Consequently, researchers have focused on expanding and emerging new (educational) institutions for children in the global north, especially for early childhood (TERVOOREN, 2021). Secondly, researchers use the term to describe childhood as an institution itself that structures and is structured by the generational relations between childhood and adulthood. Helga ZEIHER (2009) defines the institution of childhood "as a configuration of social processes, discourses, legal, temporal and spatial structures that shape children's2) lives at a particular time in a particular society" (p.105). As a result, we can see growing efforts to control childhood as an institution, for example, in Germany through the emergence of educational curricula (BETZ & EUNICKE, 2017; TERVOOREN, 2021). [16]

We link these two perspectives of institutionalization with social worlds/arenas maps: Arenas of childhood are characterized by (adult-led) formal institutions in which children spend a significant part of their time and by a growing interest in governing childhood as an institution. This leads to the establishment of new or modified institutions and/or social worlds with a shared interest in designing childhood. Following this approach, the question for social worlds/arenas maps is: Besides (and with) institutionalized forms of collectivities and in the situation of a growing institutionalization of childhood, how can we grasp the collective action of children in, connected to, and outside of institutions? We answer this question empirically based on the project presented below. [17]

3.1.1 Background of the project: The order of the family in home-school relations

In Germany, there has been a public interest in governing childhood as an institution. Beginning in the 1980s, families, especially parents, have been made more responsible for the (successful) upbringing of their children (ibid.). In educational policy debates, there has thus been a request to intensify parental work (JERGUS, KRÜGER & ROCH, 2018) in elementary schools. In this project, Nicoletta EUNICKE researched the situation of the order of the family in relation to the elementary school in Germany. They conceptualized this order of the family (DONZELOT, 1979 [1977]) in home-school relations with a generational perspective (PUNCH, 2020) and the dispositif3) (FOUCAULT, 1978a [1977]) as a theoretical framework. They focused on the generational relations that order and stabilize specific and powerful knowledge about how the family is reconstructed in home-school relations. They designed their study by adopting "[m]ultisite strategies" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.228) through which childhood and family are ordered in/through different social worlds/arenas, including heterogeneous perspectives focusing on school staff, policy and, most importantly, on children that have been widely marginalized in research on home-school relations (BETZ, BISCHOFF-PABST, EUNICKE & MENZEL, 2020). The sample and data collection included qualitative guided interviews (BROOKER, 2020) with children (average age 8-9, n=42), their teachers (n=6), one school principal and two school social workers from five heterogeneous elementary schools in Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate in Germany. In the interviews, conducted in the context of the study "Children Between Barriers and Chances" (Goethe-University Frankfurt/Main and Bertelsmann Foundation), EUNICKE and their colleagues focused on children's experiences with home-school relations.4) EUNICKE further included political-governmental documents as well as documents on and materials from the respective schools under observation in the sample. They used all four types of maps available in SA circularly and created memos and several different maps; focusing on positional maps was particularly insightful for the analysis (EUNICKE & MIKATS, 2023). The following section, however, focuses on social worlds/arenas maps. [18]

3.1.2 Empirical illustration: Looking out for children with a social worlds/arena map

In the following discussion of EUNICKE's social worlds/arena map, we argue that because of the institutionalization of childhood and the organizational focus of social worlds/arenas maps, researchers are at risk of rendering children invisible. With the map, EUNICKE showed how different social worlds struggle in the arena—which, in this particular map, is the order of the family in home-school relations. This map is a condensed version with the aim of better readability.

Figure 1: Social worlds/arena map: Order of the family in home-school relations. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 1. [19]

Firstly, we draw attention to the empirical relevance of the (theoretical thesis of) institutionalization of childhood (and family when it is constructed as a place of upbringing for children5)). EUNICKE mapped the social world of the state as very dominant across the arena and included various segments such as the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the federal states. For example, the Ministry of Education in Rhineland-Palatinate ran a coordination office for parental work, which operated a website for parents. Through this, they published various flyers and other discourse materials (CLARKE et al., 2018) through which they shaped home-school relations. Additionally, other social worlds (e.g., training institutes, teacher representative councils, or the sciences) were professionalized social worlds meaning that people—namely adults—spent their (mostly paid) work time here. They could draw on financial resources and had a high symbolic power (e.g., training certificates and institutionalized structures). So, although the arena was about family in home-school relations, it was not only school or family-internal social worlds which were concerned with institutionalizing childhood and family. In doing these social worlds/arenas maps, EUNICKE turned their analytical attention to these many and often highly professionalized social worlds, which were especially important not only for this researched situation, but for most arenas of childhood. However, by looking at this spectacle (KATZ, 2008) of social worlds, researchers are at risk of rendering children invisible, as discussed in the following arguments. [20]

Secondly, we observe the position of children in this social worlds/arena map. Most obviously, children can be located as pupils in their councils. At first glance they can be studied by analogy to similar social worlds, such as the parent council (Sections 3.3 and 4). In both social worlds (pupil and parent councils) EUNICKE clustered various segments. Children are, for example, included in social worlds like the class conference or the state pupil representatives. Thus, at a first glance, children seemed very engaged in the arena. However, EUNICKE plotted elementary school pupils as implicated actors at the top of the map. This was due to the elementary school having been designed, for example, by law, as a place where children first had to be introduced to political action within the school. Only since the passing of a new version of the Rhineland-Palatinate School Act in June 2020 has it been mandated that primary school pupils also participate in a representative body6). In the past, this was simply a vague appeal rather than being conceived as a mandate to be institutionalized; collective rights were thus much weaker. Consequently, for the present sample, there were class representatives but no pupil councils, so children were "not organized into a social world of collective actors" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.154). Therefore, EUNICKE drew this social world into the arena on a large scale and with only a few overlaps. Furthermore, children might represent their own and other children's interests in the formalized social world of class representatives. Still, they represent themselves as pupils, which is only a tiny part of being a child in home-school relations. To summarize, in doing this social worlds/arena map, EUNICKE related social worlds, including children, to other social worlds and followed the child through the map.7) This relational perspective revealed that children in this arena are seldom collectively organized and, if so, not as children but in their position as older pupils in organized settings. [21]

Thirdly, we raise the question as to the extent actors in informal social worlds have their say in this arena when the researchers and readers (by engaging with and looking at the map) focus on the multiplicity of formalized social worlds. Therefore, as EUNICKE's interest in the project was especially in children in this situation, they mapped another social world arena map in which they centered on children's experiences. This methodological step is a contemplation towards collective action of children in child cultures as peer group research as introduced by William A. CORSARO (2003). In the interviews, children spoke very little about their class representative or the school conference. Instead, they highlighted more silent, short-term, and loose engagement. For example, they worked collectively to prevent their teacher from sending photographs of them to their parents on a school trip, which also points to an arena of children's privacy. In doing this map, EUNICKE de-centers power away from institutionalized forms of actions. Following Michel FOUCAULT (1978b [1976]), power is not only oppressive but also productive and not owned by social worlds, but re-produced in everyday interactions by, for example, subjects who are not necessarily collectively organized: "Power passes through the individual who constituted it" (p.83). Rainer DIAZ-BONE (2013) argued that CLARKE was "locating power somewhat simply with those who rule, rather than conceiving of power as an organized effect that need not have a socio-structural center" (§20). With the third point we draw attention to researchers' risk to render children invisible (again) as "passive subjects of social structures and processes" (PROUT & JAMES, 1990, p.8) in social worlds/arenas maps. [22]

Altogether, we illustrated with these three empirical and theoretical points the risk of rendering children's short-term and loose forms of collectivization invisible with a multitude of other highly institutionalized social worlds. In the following theses, we focus on two specific aspects of analyzing children in the position of implicated actors on social worlds/arenas maps. [23]

3.2 Thesis 2: Researchers cannot (yet) capture the intragenerational relations of children (as implicated actors)

In this project by Claudia GLOTZ, researchers used social worlds/arenas maps to investigate the relationship of children (e.g., as pupils) as implicated actors with various social worlds. CLARKE (2005) claimed that, by creating social worlds/arenas maps, researchers analyze relations of powerful actors and "actors who are silenced" (p.86); these are, in our case, the generational relations of adults and children. In the following section, we argue that by reconstructing children as implicated actors in social worlds/arenas maps, researchers cannot (yet) capture the intragenerational relations of implicated actors. Therefore, with this second thesis, we zoom into the map and focus on children as implicated actors and their intragenerational concerns. [24]

Many childhood studies researchers have referred to the generational order as an important concept in theorizing relations of and between children and adults (BÜHLER-NIEDERBERGER, 2020 [2011]). Samantha PUNCH (2020) declared that, next to the intergenerational order of childhood and adulthood, there are also intragenerational relations "which may shape the generational orderings" (p.134). Intragenerational relations of children emerge between siblings of different ages (PUNCH, 2005) or through their social positioning (BETZ, 2008). Tanja BETZ described how some children's differences arise according to their pocket money: Some children have access to different leisure activities others cannot afford. Especially in school, inter- and intragenerational relations are relevant in relationships with peers and teachers (ECKERMANN, 2017). Hence, Friederike HEINZEL (2019) pointed out that in addition to intergenerational relationships, intragenerational relationships should also be considered in school because "overall, a fundamental generational constitution of the education and upbringing, development and socialization processes can be assumed, whereby daily intergenerational, as well as intragenerational interaction processes, recur and are formative in the elementary school" (p.283). Regarding social worlds/arenas maps, we raise the question of how intragenerational aspects of interaction can also be considered, especially regarding the group of implicated actors. [25]

3.2.1 Background of the project: The concept of dialogical learning in everyday school life

Before discussing the way GLOTZ dealt with intragenerational relationships, we briefly explain the context of the project, which was located by GLOTZ in the field of German lessons.8) The researcher examined communicative action (REICHERTZ, 2013) of adults (teachers) and children (as pupils) in the elementary school classroom while writing texts. Specifically, GLOTZ reconstructed communicative action in teaching phases in the study which, according to the teachers, were conducted in accordance with the didactic concept of dialogical learning (RUF & GALLIN, 2014 [1999]). With the concept of dialogical learning, teachers aim to frame instruction as an exchange between adults and children. Therefore, teachers emphasize the children's co-constructive part in the class design (ibid.). To answer the question of how adults and children create a social order by acting, GLOTZ analyzed reciprocal communicative action by considering the organizational setting. With recourse to the assumptions of communicative constructivism (KELLER, KNOBLAUCH & REICHERTZ, 2013), GLOTZ reconstructed relations of adults and children as well as the intragenerational relations of the children during these lessons. [26]

In the study, GLOTZ followed an ethnographic research style (BREIDENSTEIN, HIRSCHAUER, KALTHOFF & NIESWAND, 2020 [2013]). They collected data in several field visits over two years to different classes (grade 1-4) in an elementary school in Austria by combining participant observation with video and audio recordings, interviews, and artifact analysis (ibid.). GLOTZ integrated grounded theory coding procedures (STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1996 [1990]), sequence analytical procedures (DEPPERMANN, 2008 [2001]) and mapping procedures of SA (CLARKE et al., 2018) to analyze the data. [27]

3.2.2 Empirical illustration: Children's actions from an intragenerational perspective

In this section, we discuss the thesis that in creating social worlds/arenas maps, GLOTZ reconstructed children as implicated actors in social worlds/arenas maps but could not (yet) capture the intragenerational relations of implicated actors. In her memos, GLOTZ identified the dominance of adults and the organizational dimension for interaction processes in lessons as a major category in the analytic process. Consequently, GLOTZ produced social worlds/arenas maps to reconstruct the actions of adults concerning institutional, social-organizational, and discursive dimensions (CLARKE et al., 2018). GLOTZ reconstructed different social worlds and the powerful position of adults. With the map, GLOTZ showed that boundaries between social worlds seemed fluid for adults, and participation in multiple worlds was necessary and meaningful for them. By contrast, children built a group of implicated actors. Based on GLOTZ's research interest, the challenge was the consideration of children's actions. This led GLOTZ to consider whether creating a map for implicated actors (children) could be a helpful addition for looking at intragenerational relationships. With the following passage, we argue how intragenerational order can change the working process in lessons:

"The pupils are working on a task in different locations in the classroom. Then suddenly, I see a pupil getting up and walking toward another pupil. The two pupils start talking to each other briefly and look around. Then they both get up and approach another pupil sitting on the carpet in front of the blackboard. Now, the three pupils begin to talk to each other and look around. The pupil on the carpet shakes their head and the two other pupils walk over to another pupil sitting at a table. When they get to see the teacher, the pupil sitting at a table stands up. Then all three of them approach the teacher. I hear one of the three pupils ask the teacher to transfer the session outside because of the nice weather. The teacher first looks at her watch and then out of the window. They seem to contemplate. At the same time, more and more pupils get up and join the other three pupils next to the teacher. Now there is a group of pupils - maybe nine or ten. Also, the other pupils in the room stop their work and look at the group formed around the teacher. The pupils start to talk all at once and jointly try to convince the teacher. After a short while, the teacher seems convinced and the children shout: "We're going outside!" I notice that a few pupils in the classroom say "Ohhhh no!" while others start to pack up their work materials and leave the classroom" (observation protocol, no. 15). [28]

The reconstruction of the actions of joint groups is one part of social worlds/arenas maps and, with the vignette, we illustrated how children participated in decisions during the lessons. In this vignette, one child started an initiative and searched for partners who shared his interest. With the ever-increasing number of children, the pressure on the adult rose and, in the end, the children went outside. Therefore, the children created a collective group to enforce their interests. To catch the intragenerational order, GLOTZ zoomed in on the group of implicated actors. [29]

Firstly, with the vignette, we showed that there were differences between children. The first child selected partners and chose just three of the others. The reason for this selection was not apparent for the observer. There were different possibilities how the order was structured and it "can also be carried out in different ways" (PUNCH, 2020, p.134)—here children may be friends or part of the same peer-group in class. In lessons, children must meet the "curricular requirements of school and teaching and, at the same time, they act as part of a peer culture" (ECKERMANN, 2017, p.12). To create a map of social worlds/arenas, "the divergent perspectives of different collective actors are of great importance for the perception and definition of the various social worlds" (STRÜBING, 2021 [2004], p.120). As a result, GLOTZ analyzed different groups of implicated actors: children who (can) start a project, join the project by themselves, do nothing, and children who are not involved. [30]

Secondly, we wanted to point out that there were children who were not actively involved in this process. The child on the carpet was not part of this group and later they did not join the group that was formed around the adult. They did not want to or could not join the group. Such intragenerational relations, however, are also shaped by "gender, age, ethnicity and class" (PUNCH, 2020, p.134). Nevertheless, in the end, all children in the classrooms had to follow the first child's initiative and go outside. Although some children did not want to ("Oh no!")—they were not heard (or silenced) by other children or by the adult. In other words, they were the implicated of the implicated. [31]

With both examples, we showed how GLOTZ zoomed in to the group of implicated actors to illustrate these intragenerational relations between the pupils as implicated actors, because "interactions in the primary school classroom are accompanied by intergroup processes and social differentiation processes" (HEINZEL, 2019, p.284). Using the words of CLARKE et al. (2018), you can "do such maps perspectively—from the perspective of one particular social world in the arena" (p.253), we propose creating these maps from the perspective of the implicated actors. With the help of zooming in, different perspectives of children can be examined with social worlds/arenas. Considering "fresh ways into social science data" (CLARKE & STAR, 2008, p.128), one cannot concentrate on one group, but must zoom out again to reconstruct the position of children—as we argue in the next section. [32]

3.3 Thesis 3: Researchers cannot fully account for a relational understanding of children and childhood

In seeking to reimagine childhood studies, SPYROU et al. (2018) have advocated for a relational, connective, and linked approach to research children and childhood. This means that children's lives and childhood should not be examined solely on the micro level—as researchers in childhood studies preferred to see what they assumed as a "competent, agentic child" (p.11)—but should also be acknowledged beyond children's immediate environments. To do so, researchers need to "decenter children and childhood" by attending to "those entangled relations which materialize, surround, and exceed children as entities and childhood as phenomenon diversely across time and space" (p.6) and on various scales (ANSELL, 2009). Thus, we drew from the mapping techniques of CLARKE et al.'s (2018) SA to examine relationalities of the child and childhood. In doing so, we were following an examination of the child and childhood in which researchers must assume an analytical "relational posture not only toward bodies and persons but also toward objects, technologies, systems, epistemes, and historical eras" (SPYROU et al., 2018, p.6). With Thesis 3, we aim to bridge Thesis 1 and 2 (Sections 3.1 and 3.2) by focusing on the relationalities of children and childhood in social worlds/arenas maps. [33]

SPYROU et al. (2018) argued that, in order to understand a phenomenon (using political economy as an example), it would require both an understanding of how children and childhood are shaped by the phenomenon as well as how children and childhood are shaping the phenomenon. However, as previously pointed out, when children are characterized as implicated actors, they are considered not to be involved in social action. CLARKE commented in a conversation with KELLER (2014), on the concept of implicated actors, as follows: "I sought to conceptualize actors in situations who were not themselves active—agentic—in that situation, but who were implicated by the actions of other actors" (§98). By using the term agentic, CLARKE seemed to suggest a static (actors/actants have agency or not) and dualistic (active/passive) understanding of agency. This is an understanding that we see as being in conflict with a relational understanding of agency and power, upon which, however, CLARKE et al. (2018) built in SA. In line with a relational understanding, researchers in childhood studies (e.g., ESSER, BAADER, BETZ & HUNGERLAND, 2016a; OSWELL, 2013) have proposed that agency is not to be understood as a property of actors/actants but as complex, situated, and collective performance, mediated by actors and materialities9). Whether and how researchers may account for a relational understanding of children and childhood with the concept of implicated actors becomes a central concern. Thus, the following questions for doing social worlds/arenas maps must be raised: How can we grasp multidimensional involvements of children (and childhood) in social worlds/arenas—as or beyond being implicated actors? [34]

3.3.1 Background of the project: Organizing family life in relation to home-based working

In the project "When Home is a Workplace,"10) Jana MIKATS examined the situation of family life in relation to home-based working. They looked at people that were working in the same unit in which they lived together as a family with younger children (3-10 years) and their partners. To examine how family life was organized on spatiotemporal, material, and conceptual dimensions, MIKATS reconstructed practices of family life. [35]

To conceptualize family life in relation to home-based working, MIKATS drew from the family practice approach (MORGAN, 2013) and an overall practice-theoretical framework (RECKWITZ, 2003; SHOVE, PANTZAR & WATSON, 2012). David MORGAN (2011) conceptualized family practices as daily, often taken-for-granted activities (rather than "rational calculation" [§10]) that are interrelated with wider social relations and meanings. Lynn JAMIESON (2020) welcomed this turn to relational approaches in family research, as, in doing so, researchers would avoid viewing families "as small groups of powerless individuals in the path of global forces" (p.221). Julie SEYMOUR (2020) further argued that, with relational approaches, researchers would recenter children in family research by focusing on "broader familial settings in which children's lives are experienced" (p.12). In these ways, researchers, using relational approaches in family research, also contribute to deepening the understanding of children and childhood. [36]

For the empirical study, MIKATS included 11 families (15 home-based workers: 11 women, 4 men; 6 male partners and 19 children) by using different qualitative methods: problem-centered interviews (WITZEL, 2000) with the home-based workers, photo interviews (KOLB, 2008) in combination with socio-spatial network games (SCHIER, SCHLINZIG & MONTANARI, 2015) with all family members as well as shadowing11) (CZARNIAWSKA, 2007). In the analysis of the data, analytical strategies of constructivist grounded theory methodology (CHARMAZ, 2014 [2006]) and SA (CLARKE et al., 2018) were used and combined (for details on this combination see BRÜCK, MIKATS & WEYRICH, 2023). [37]

MIKATS drew from social worlds/arenas "to locate the research project in its broader situation" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.187). To create the map, MIKATS followed the advice of placing "the subject of your research" (CLARKE, FRIESE & WASHBURN 2015, p.175) in the center of the map and the social worlds around it. They, however, reconstructed the social worlds "from the perspective(s) of only one segment of one social world" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.155), namely the family members. MIKATS undertook different adaptations of the social worlds/arenas map to correspond to the researched phenomenon and reconcile the key concepts. [38]

3.3.2 Empirical illustration: Grasping multidimensional involvements of children (and childhood)

In Figure 2, we show a version of the map with an arena—reconciliation of work and family life—in the middle. Here, both children and families can be understood as implicated actors. Their interests, needs, responsibilities, and deficits were presumably negotiated and defined by different social worlds, in which families or children were largely unable to participate or represent themselves. Children were implicated not only as family members, but also as children, while their parents had the option of collective (self-) representation as employees, self-employed or creative professionals. Children were dually implicated, suggesting that they were in a weaker position vis-à-vis parents as adults. However, in the following, we want to point out two challenges encountered by MIKATS by rendering children and families as implicated actors.

Figure 2: Social worlds/arena map: Big picture of the situation family life in relation to home-based working. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 2. [39]

First, in the reconstruction of practices, MIKATS identified the physical presence and absence of children in the home space as a central aspect of organizing family life in relation to home-based working (e.g., work tasks and children's activities were mutually adapted when they were performed in co-presence). Therefore, agency, understood as "the capacity to do and to make a difference," was "dispersed across an arrangement" (OSWELL, 2013, p.70)—of (present and absent) family and work-related elements—which, however, could not be examined when children were perceived as implicated and thus not involved in social action. [40]

Second, MIKATS did not draw on social worlds and arenas theory to conceptualize the situation (family life in relation to home-based working). Families could not be viewed as collectively organized actors because "they likely do not even know each other, much less share commitment to action as a collective"12) (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.154). We did not see a full alignment of the researchers' underlying understanding of family as fluid and interrelated practices (see Section 3.3.1), and thus families could not be considered a social world. On the contrary, MORGAN (2013) emphasized that the boundaries of what is conceived as family need to be answered empirically, for instance by examining how family practices are co-constituted by intersecting practices of work and care. Thus, we recognize affinities between this perspective and the concept of the arena that, however, has been (predominantly) defined as a "discursive site" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.148). Consequently, MIKATS adapted the mapping process to a practice-theoretical framework to facilitate the understanding of family as interrelated practices and children (and other family members) as carriers of those practices13). [41]

MIKATS was inspired by RECKWITZ' (2003) understanding of society as a nexus of interrelated complexes of practices that are structured by two different modes: social fields, which thematically relate practices (i.e., economies or organizations) and forms of life, which structure everyday life as well as the life course of human actors in specific ways (i.e., milieus). However, social fields and forms of life consist of the same elements and practices (ibid.). By placing the situation—instead of the arena—in the middle of the map, MIKATS was able to illustrate how different social fields intersected with practices of family life (as segments of a form of life) that were related and carried by the different family actors. [42]

By adapting social worlds/arenas maps in this way, MIKATS deepened the understanding that "scenes and sites of collective action [...] are fully present and quite consequential in the situation that the individuals being studied are describing and in which their specific (inter)actions take place" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.155), even when these individuals had been characterized as implicated actors. Doing this map furthermore facilitated their understanding that all elements and levels or scales are the situation (see also ANSELL, 2009). By mapping social worlds/arenas as interrelated complexes of practices, MIKATS systematically thought about institutional and organizational elements (e.g., opening hours of childcare facilities or maternity leave regulations) that are (co-) constitutive for everyday family life and thus children and childhood and vice versa14). With this analytical approach, MIKATS was able—in the words of SPYROU et al. (2018): "To identify and examine those entangled relations which materialize, surround and exceed children as entities and childhood as a phenomenon diversely across time and space" (p.8). [43]

Approaching the situation from this perspective allowed us a view on implicated actors beyond a merely discursive perspective (CLARKE et al., 2018). In the analysis of children's (non-discursive) involvements in practices, MIKATS was able to consider "the question of how children's participation in a variety of very different practice ensembles is connected to the potential for upsetting and challenging routines which, in turn, provides the potential for the development of more complex capacities to act" (BOLLIG & KELLE, 2016, p.45). So, children in their regular attendance of childcare institutions—as well as the refusal or incapacity (e.g., sickness or closing) to do so—challenged the daily organization of family life in relation to home-based working. Children and their physical absence and presence in the home space related to and re-shaped working and caring practices (for details see MIKATS, 2020). MIKATS directed thus their analytical interest towards "the discourses and practices in which different positions, forms of authority, responsibilities and access to resources are distributed across the generations" (ESSER, BAADER, BETZ & HUNGERLAND, 2016b, p.7). In short, we believe that researchers can undertake a relational, connective, and linked approach to researching children and childhood with social worlds/arenas maps—but only with appropriate conceptual and methodological adaptations. [44]

In our research of children (as implicated actors) in social worlds/arenas maps in SA-projects, we raised methodological concerns that we discussed in this article based on three empirical projects. On one hand, we have shown the potential of social worlds/arenas maps for generational analysis of collective actions including adults and children. We connected this potential to the demand in childhood studies to think of childhood and adulthood relationally (FANGMEYER & MIERENDORFF, 2017) and not detached from each other. The social worlds/arenas maps were especially helpful for looking at the big picture of the situation and for understanding the constitution of the child, children, and childhood better. [45]

On the other hand, there are also challenges for the analysis and aspects the maps do "not grasp" (MATHAR, 2008, §24) without reconsidering the position of children. We addressed these challenges in three theses by focusing on 1. the institutionalization of childhood 2. intragenerational-interaction processes and 3. relationalities of children and childhoods in the context of social worlds/arenas. Based on theoretical insights of childhood studies and our own empirical experiences, we see possible shortcomings of social worlds/arenas maps for the analysis of children and/as (other possible) implicated actors (see Sections 3.1, 3.2, 3.3). To improve the analytical insight from the perspective of childhood studies, we propose questions that focus on children and implicated actors in social worlds/arenas maps in analogy to CLARKE et al.'s (2018) questions for social worlds/arenas analysis.

Considering the institutionalization of the childhood arenas: Does the researcher grasp the collective action of children in, connected to, and outside of institutions, besides (and with) institutionalized forms of collectivities, and in the situation of a growing institutionalization of childhood? Which (possibly loose, silence, and short-term) collective forms of actions (of children) does the researcher not (yet) grasp with the map?

Addressing intergenerational and intragenerational relations of children: Does the researcher grasp intragenerational relations between children as implicated actors? Which different or unequal relations between children can be examined in their collective action?

Accounting for relationalities of children and childhood: Does the researcher grasp multidimensional involvements of children (and childhood) in social worlds/arenas? Which dispersed and relational (with other human and non-human aspects) capacities to make a difference become visible by looking at implicated actors beyond a merely discursive perspective? [46]

CLARKE et al. described the gain of analyzing implicated actors as follows: "Through understanding the discursive construction of implicated actors and actants, analysis can grasp a lot about the social worlds, their arena(s), and some consequences of those constructions for the less powerful" (p.77). However, to understand not merely "some consequences of those constructions" (ibid.) for children and childhood but to center on the involvement of the child, children and childhood in the situation, the question should not be whether the child is agentic or "a passive presence within overwhelming structural determinations" (SPYROU et al., 2018, p.7). Rather, the goal should be to examine "the relational and interdependent aspects of children's lives as well as the ethics and politics which characterize them" (p.6). Thus, it becomes necessary to broaden the conceptual toolbox of SA, and especially implicated actors, as we propose with this contribution. [47]

We would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their productive feedback, our colleague Britta MENZEL, and the participants of the colloquium of Tanja BETZ as well. The proofreading was financed by the internal university research funding from the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz, Germany.

1) All translations from non-English texts are ours. <back>

2) We argue that the configuration of childhood shapes the lives of adults as well. <back>

3) Dispositifs are a system of heterogeneous ensembles of disparate elements, including discursive and non-discursive practices (WRANA & LANGER, 2007). CLARKE et al. (2018) saw resonance between the concept of dispositif and situation, as in both concepts "the relations per se […] are potent, not the entities themselves" (p.83). <back>

4) The research procedure in the project was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the German Society for Educational Science and the data protection commissioners of the two federal states (for details see BETZ et al., 2020). <back>

5) By placing the social world of family lightly in the arena on this map, EUNICKE showed that only a small part of what family is and does is made relevant in this arena. Family is mapped also as an implicated actor (top half of the map) to indicate that in the arena family does not act collectively. Individual family actors, however, are collectivized in different social worlds. <back>

6) Schulgesetz Rheinland-Pfalz [School Act Rhineland-Palatinate], 2004, §31(1), https://landesrecht.rlp.de/bsrp/document/jlr-SchulGRP2004rahmen [Accessed April 30, 2023]. <back>

7) The idea to follow the child relates to Arjun APPADURAIs (1986) thoughts about following things through different -scapes (see CLARKE et al., 2018, for details). <back>

8) This section is about GLOTZ's doctoral thesis. Prior the start of the project, there was a presentation for all participants especially regarding ethical questions. Additionally, the exposé had to include a section on research ethics that was reviewed and approved by the doctoral advisory board of the Faculty of Linguistics and Literature at LMU Munich. <back>

9) Relational agency is used here as an umbrella term to refer to recent developments to the concept of agency within the field of childhood studies. While this concept has many overarching similarities, researchers discern between nuanced theoretical differences (for details see ESSER et al., 2016a). <back>

10) The research project is MIKATS' doctoral thesis, which they are completing in sociology at the University of Vienna. The exposé for the doctoral thesis had to include a separate section on research ethics that was reviewed and approved by the doctoral advisory board of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Vienna prior to the start of the project. <back>

11) The aim of this method is to follow a person (or thing) for a specific time, meaning that the observation is not tied to a specific location and does not focus on the researcher's participation in the situation, but detailed observation by the researcher. <back>

12) Whether families share a commitment to collective action certainly differs between research foci and theoretical standpoints. <back>

13) For affinities between social worlds/arenas theory and practice theories see, for example, CLARKE et al., 2018; POHLMANN, 2020; STRÜBING, 2017; STRÜBING, 2021 [2004]. <back>

14) This also facilitates a perspective on children and childhood between and across institutions as ESSER and SCHRÖER (2019) have proposed as a trans-organizational approach. <back>

Alanen, Leena (2001). Explorations in generational analysis. In Leena Alanen & Berry Mayall (Eds.), Conceptualising child-adult relations (pp.11-22). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Ansell, Nicola (2009). Childhood and the politics of scale: Descaling children's geographies? Progress in Human Geography, 33(2), 190-209.

Appadurai, Arjun (1986). The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Betz, Tanja (2008). Ungleiche Kindheiten: Theoretische und empirische Analysen zur Sozialberichterstattung über Kinder. München: Juventa.

Betz, Tanja & Eunicke, Nicoletta (2017). Kinder als Akteure in der Zusammenarbeit von Bildungsinstitutionen und Familien? Eine Analyse der Bildungs- und Erziehungspläne. Frühe Bildung, 6(1), 3-9.

Betz, Tanja; Bischoff-Pabst, Stefanie; Eunicke, Nicoletta & Menzel, Britta (2020). Children at the crossroads of opportunities and constraints—The relationship between school and family from the children's viewpoint: their perspectives, their positions (research report 2). Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, https://doi.org/10.11586/2020042 [Accessed: April 30, 2023].

Bollig, Sabine, & Kelle, Helga (2016). Children as participants in practice. In Florian Esser, Meike S. Baader, Tanja Betz & Beatrice Hungerland (Eds.), Reconceptualising agency and childhood. New perspectives in childhood studies (pp.34-47). London: Routledge.

Bollig, Sabine; Neumann, Sascha; Betz, Tanja & Joos, Magdalena (2018). Einleitung. Institutionalisierungen von Kindheit. In Tanja Betz, Sabine Bollig, Magdalena Joos & Sascha Neumann (Eds.), Institutionalisierungen von Kindheit. Childhood Studies zwischen Soziologie und Erziehungswissenschaft (pp.7-20). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Breidenstein, Georg; Hirschauer, Stefan; Kalthoff, Herbert & Nieswand, Boris (2020 [2013]). Ethnografie: die Praxis der Feldforschung (3rd. rev. ed.). München: UVK.

Brooker, Liz (2020). Interviewing children. In Glenda Mac Naughton, Sharne A. Rolfe & Iram Siraj-Blatchford (Eds.), Doing early childhood research. International perspectives on theory and practice (pp.162-177). London: Routledge.

Brück, Jasmin; Mikats, Jana & Weyrich, Katharina (2023). Kombination von Kodieren und Mappen: Erfahrungen und Möglichkeiten. In Leslie Gauditz, Anna-Lisa Klages, Stefanie Kruse, Eva Marr, Ana Mazur, Tamara Schwertel & Olaf Tietje (Eds.), Die Situationsanalyse als Forschungsprogramm. Theoretische Implikationen, Forschungspraxis und Anwendungsbeispiele (pp.297-314). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Bühler-Niederberger, Doris (2020 [2011]). Lebensphase Kindheit: Theoretische Ansätze, Akteure und Handlungsräume (2nd rev. ed.). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Canosa, Antonia & Graham, Anne (2020). Tracing the contribution of childhood studies: Maintaining momentum while navigating tensions. Childhood, 27(1), 25-47.

Charmaz, Kathy (2014 [2006]). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Clarke, Adele E. (1991). Social worlds/arenas theory as organizational theory. In David R. Maines (Ed.), Social organization and social process: Essays in honor of Anselm Strauss (pp.119-158). New York, NY: de Gruyter.

Clarke, Adele E. (2005). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the postmodern turn. London: Sage.

Clarke, Adele E. & Keller, Reiner (2014). Engaging complexities: Working against simplification as an agenda for qualitative research today. Adele Clarke in conversation with Reiner Keller. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 15(2), Art. 1, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-15.2.2186 [Accessed: April 30, 2023].

Clarke, Adele E. & Montini, Theresa (1993). The many faces of RU486: Tales of situated knowledges and technological contestations. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 18(1), 42-78.

Clarke, Adele E. & Star, Susan L. (2008). The social worlds framework: A theory/methods package. In Edward Hackett, Olga Amsterdamska, Michael Lynch & Judy Wajcman (Eds.), The handbook of science and technology studies (pp.113-139). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Clarke, Adele E.; Friese, Carrie & Washburn, Rachel (2015). Introduction. In Adele E. Clarke, Carrie Friese & Rachel Washburn (Eds.), Situational analysis in practice: Mapping research with grounded theory (pp.171-194). Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

Clarke, Adele E.; Friese, Carrie & Washburn, Rachel (2018). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the interpretive turn (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Corsaro, William A. (2003). We're friends, right? Inside kid's culture. Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press.

Czarniawska, Barbara (2007). Shadowing: And other techniques for doing fieldwork in modern societies. Copenhagen: Liber.

Deppermann, Arnulf (2008 [2001]). Gespräche analysieren. Eine Einführung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Diaz-Bone, Rainer (2013). Review Essay: Situational Analysis – Strauss meets Foucault?. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 14(1), Art. 11, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-14.1.1928 [Accessed: April 30, 2023].

Donzelot, Jacques (1979 [1977]). Die Ordnung der Familie (transl. by U. Raulff). Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Eckermann, Torsten (2017). Kinder und ihre Peers beim kooperativen Lernen: Differenz bearbeiten – Unterschiede herstellen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Esser, Florian & Schröer, Wolfgang (2019). Infrastrukturen der Kindheiten – ein transorganisationaler Zugang. Zeitschrift für Soziologie der Erziehung und Sozialisation, 39(2), 119-133.

Esser, Florian; Baader, Meike; Betz, Tanja & Hungerland, Beatrice (Eds.) (2016a). Reconceptualising agency and childhood: New perspectives in childhood studies. London: Routledge.

Esser, Florian; Baader, Meike; Betz, Tanja & Hungerland, Beatrice (2016). Reconceptualising agency and childhood: An introduction. In Florian Esser, Meike Baader, Tanja, Betz, & Beatrice Hungerland (Eds.), Reconceptualising agency and childhood: New perspectives in childhood studies (pp.1-16). London: Routledge.

Eunicke, Nicoletta & Mikats, Jana (2023). Zum Verhältnis von implicated actors und Positions-Maps: Kindheitstheoretische Inspirationen für die Situationsanalyse. In Leslie Gauditz, Anna-Lisa Klages, Stefanie Kruse, Eva Marr, Ana Mazur, Tamara Schwertel & Olaf Tietje (Eds.), Die Situationsanalyse als Forschungsprogramm. Theoretische Implikationen, Forschungspraxis und Anwendungsbeispiele (pp.205-219). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Fangmeyer, Anna & Mierendorff, Johanna (2017). Kindheit und Erwachsenheit. Relationierungen in und durch soziologische Forschung und Theoriebildung. Einleitung. In Anna Fangmeyer & Johanna Mierendorff (Eds.), Kindheit und Erwachsenheit in sozialwissenschaftlicher Forschung und Theoriebildung (pp.10-20). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Foucault, Michel (1978a [1977]). Ein Spiel um die Psychoanalyse. Gespräch mit Angehörigen des Département de Psychoanalyse der Universität Paris VIII in Vincennes (transl. by M. Metzger). In Michel Foucault (Ed.), Dispositive der Macht: Über Sexualität, Wissen und Wahrheit (pp.118-175). Berlin: Merve.

Foucault, Michel (1978b [1976]). Recht der Souveränität/ Mechanismus der Disziplin. Vorlesung vom 14. Januar 1976 (transl. by E. Wehr). In Michel Foucault (Ed.), Dispositive der Macht: Über Sexualität, Wissen und Wahrheit (pp.75-95). Berlin: Merve.

Gauditz, Leslie; Klages, Anna-Lisa; Kruse, Stefanie; Marr, Eva; Mazur, Ana; Schwertel, Tamara & Tietje, Olaf (Eds.) (2023). Die Situationsanalyse als Forschungsprogramm. Theoretische Implikationen, Forschungspraxis und Anwendungsbeispiele. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Gruenbergkollektiv (2020). Pragmatism reloaded. Die Siedlerinnen von Chicago, https://digital-humanities.uni-tuebingen.de/webcomics/pragmatism-reloaded/ [Accessed: April 30, 2023].

Grunau, Thomas (2021). Die pädagogisierte Welt des Kinderfußballs. Zwischen privaten und öffentlichen Erziehungssphären. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Heinzel, Friederike (2019). Zur Doppelfunktion der Grundschule, dem Kind und der Gesellschaft verpflichtet zu sein – die generationenvermittelnde Grundschule als Konzept. Zeitschrift für Grundschulforschung, 12(2), 275-287.

Holloway, Sarah L. & Pimlott-Wilson, Helena (2014). Enriching children, institutionalizing childhood? Geographies of play, extracurricular activities, and parenting in England. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 104(3), 613-627.

Jamieson, Lynn (2020). Sociologies of personal relationships and the challenge of climate change. Sociology, 54(2), 219-236.

Jergus, Kerstin; Krüger, Jens O. & Roch, Anne (2018). Elternschaft zwischen Projekt und Projektion. In Kerstin Jergus, Jens O. Krüger & Anne Roch (Eds.), Elternschaft zwischen Projekt und Projektion. Aktuelle Perspektiven der Elternforschung (pp.1-27). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Katz, Cindi (2008). Childhood as a spectacle: Relays of anxiety and the reconfiguration of the child. Cultural Geographies, 15(1), 5-17.

Keller, Reiner; Knoblauch, Hubert & Reichertz, Jo (Eds.) (2013). Kommunikativer Konstruktivismus. Theoretische und empirische Arbeiten zu einem neuen wissenssoziologischen Ansatz. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Kolb, Bettina (2008). Involving, sharing, analyzing—Potential of the participatory photo interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum Qualitativ Social Research, 9(3), Art. 12, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.3.1155 [Accessed: April 30, 2023].

Liebel, Manfred (2020). Unerhört. Kinder und Macht. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Marr, Eva (2020). Vorstellungen von einem guten Leben bei Heranwachsenden in mehrfach belasteten Lebenszusammenhängen. Eine multiperspektivische Fallstudie. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Mathar, Tom (2008). Review essay: Making a mess with situational analysis?. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 4, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-9.2.432 [Accessed: April 30, 2023].

Mikats, Jana (2020). "When mom and dad are working, I build LEGO". Children's perspectives on everyday family life and home in the context of parental home-based work arrangements. In Sam Frankel, Sally McNamee & Loretta E. Bass (Eds.), Bringing children back into the family: Relationality, connectedness and home (pp.95-111). Bingley: Emerald.

Morgan, David H. G. (2011). Locating family practices. Sociological Research Online, 16(4), Art. 14. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.253 [Accessed: April 30, 2023].

Morgan, David H. G. (2013). Rethinking family practices. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Offenberger, Ursula (2019). Anselm Strauss, Adele Clarke und die feministische Gretchenfrage. Zum Verhältnis von Grounded-Theory-Methodologie und Situationsanalyse. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(2), Art. 6, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.2.2997 [Accessed: April 30, 2023].

Oswell, David (2013). The agency of children. From family to global human rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pohlmann, Angela (2020). Von Praktiken zu Situationen. Situative Aushandlung von sozialen Praktiken in einem schottischen Gemeindeprojekt. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(3), Art. 4, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.3.3330 [Accessed April 30, 2023].

Prout, Alan & James, Allison (1990). A new paradigm for the sociology of childhood? Provenance, promise and problems. In Allison James & Alan Prout (Eds.), Constructing and reconstructing childhood: Contemporary issues in the sociological study of childhood (pp.7-34). London: The Falmer Press.

Punch, Samantha (2005). The generationing of power: A comparison of child-parent and sibling relations in Scotland. In Loretta E. Bass (Ed.), Sociological Studies of Children and Youth (pp.169-188). Bingley: Emerald.

Punch, Samantha (2020). Why have generational orderings been marginalised in the social sciences including childhood studies?. Children's Geographies, 18(2), 128-140.

Qvortrup, Jens; Corsaro, William A. & Honig, Michael-Sebastian (Eds.) (2009). The Palgrave handbook of childhood studies. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillian.

Reckwitz, Andreas (2003). Grundelemente einer Theorie sozialer Praktiken. Eine sozialtheoretische Perspektive. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 32(4), 282-301.

Reichertz, Jo (2013). Grundzüge des Kommunikativen Konstruktivismus. In Hubert Knoblauch, Reiner Keller & Jo Reichertz (Eds.), Kommunikativer Konstruktivismus. Theoretische und empirische Arbeiten zu einem neuen wissenssoziologischen Ansatz (pp.69-96). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Ruf, Urs & Gallin, Peter (2014 [1999]). Dialogisches Lernen in Sprache und Mathematik, Vol. 1 & 2 (5th ed.). Seelze: Friedrich Verlag.

Schier, Michaela; Schlinzig, Tino & Montanari, Guilia (2015). The logic of multi-local living arrangements: Methodological challenges and the potential of qualitative approaches. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie / Journal of Economic and Social Geography, 106(4), 425-438.

Schütze, Fritz (2016). Das Konzept der Sozialen Welt Teil 1: Definition und historische Wurzeln. In Michael Dick; Winfried Marotzki & Harald Mieg (Eds.), Handbuch Professionsentwicklung (pp.74-88). Stuttgart: UTB.

Seymour, Julie (2020). Who's zooming (out on) who? Reconceptualising family and domestic spaces in childhood studies. In Sam Frankel, Sally McNamee & Loretta E. Bass (Eds.), Bringing children back into the family: Relationality, connectedness and home (pp.11-22). Bingley: Emerald.

Shove, Elizabeth; Pantzar, Mika & Watson, Matt (2012). The dynamics of social practice: Everyday life and how it changes. London: Sage.

Spivak, Gayatri C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? Postkolonialität und subalterne Artikulation. Wien: Turia + Kant.

Spyrou, Spyros; Rosen, Rachel & Cook, Daniel T. (2018). Introduction: Reimagining childhood studies: Connectivities ... relationalities ... linkages ... In Spyros Spyrou, Rachel Rosen & Daniel T. Cook (Eds.), Reimagining childhood studies (pp.1-20). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Strauss, Anselm L. & Corbin, Juliet M. (1996 [1990]). Grounded Theory: Grundlagen qualitativer Sozialforschung (transl. by N. Solveigh & H. Legewie). Weinheim: Beltz/PVU.

Strübing, Jörg (2017). Where is the Meat/d? Pragmatismus und Praxistheorien als reziprokes Ergänzungsverhältnis. In Hella Dietz, Frithjof Nungesser & Andreas Pettenkofer (Eds.), Pragmatismus und Theorien sozialer Praxis: Vom Nutzen einer Theoriedifferenz (pp.41-75). Frankurt/M.: Campus.

Strübing, Jörg (2021 [2004]). Grounded Theory und Situationsanalyse: Zur Weiterentwicklung der Grounded Theory. In Jörg Strübing (Ed.), Grounded Theory. Zur Sozialtheoretischen und epistemologischen Fundierung eines pragmatischen Forschungsstils (4th ed., pp.107-123). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Tervooren, Anja (2021). De/Institutionalisierung (in) der frühen Kindheit. Theoretische und methodologische Überlegungen. Zeitschrift für Soziologie der Erziehung und Sozialisation, 41(1), 23-39.

Viviani, Maria (2016). Creating dialogues. Exploring the "good early childhood educator" in Chile. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 17(1), 92-105.

Whisker, Craig (2018). Review: Adele E. Clarke, Carrie Friese & Rachel S. Washburn (2018). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the interpretive turn. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(3), Art. 35, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-19.3.3138 [Accessed: April 30, 2023].

Witzel, Andreas (2000). The problem-centered interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum Qualitative Social Research, 1(1), Art. 22, https://doi.org./10.17169/fqs-1.1.1132 [Accessed: April 30, 2023].

Wrana, Daniel & Langer, Antje (2007). An den Rändern der Diskurse. Jenseits der Unterscheidung diskursiver und nicht-diskursiver Praktiken. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 8(2), Art. 20, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-8.2.253 [Accessed: April 30, 2023].

Zeiher, Helga (2009). Ambivalenzen und Widersprüche der Institutionalisierung von Kindheit. In Michael-Sebastian Honig (Ed.), Ordnungen der Kindheit: Problemstellungen und Perspektiven der Kindheitsforschung (pp.103-126). Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Nicoletta EUNICKE is a research associate at the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz (Germany) at the Institute of Education. Her main fields of work are theories and methodologies of childhood studies, family research, home-school relations and qualitative methods (especially biographical interviews and group discussions with children and situational analysis).

Contact:

Nicoletta Eunicke, M.A.

Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz

Educational science with a focus on childhood studies

Jakob-Welder-Weg 12, 55128 Mainz, Germany

Tel.: +49 6131/3927934

E-mail: Eunicke@uni-mainz.de

URL: https://www.allgemeine-erziehungswissenschaft.uni-mainz.de/nicoletta-eunicke-m-a/

Jana MIKATS is a lecturer at the University of Graz and the University of Klagenfurt (Austria) and is completing her dissertation "When Home is a Workplace. Practice of Family Life, Gender and Childhood in Relation to Home-Based Working" in Sociology at the University of Vienna. Previously, she worked in the research area "Sociology of Gender and Gender Studies" at the Institute of Sociology, University of Graz (Austria). She focuses in her work on issues related to family research, childhood studies, gender studies, and qualitative methods (especially multi-method approaches, grounded theory, and situational analysis).

Contact:

Jana Mikats, M.A.

University of Vienna

Vienna Doctoral School of Social Sciences

Universitätsstraße 7

1010 Vienna, Austria

E-mail: jana.mikats@gmx.at

Claudia GLOTZ is a lecturer at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University in Munich at the Faculty of Languages and Literatures. She is completing her dissertation "In Search of Dialogue. An Ethnographic Study of Classroom Communication" in German language and literature education. She focuses in her work in issues related to writing research, dialogical learning, child literacy, and qualitative methods (especially educational ethnography, grounded theory methodology and situational analysis).

Contact:

Claudia Glotz, M.A.

Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich

Faculty of Languages and Literatures

Department I: German Studies, Comparative Literature, Nordic Studies and German as a Foreign Language

Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1

80539 München, Germany

E-mail: Claudia.Glotz@lmu.de

Eunicke, Nicoletta; Mikats, Jana & Glotz, Claudia (2023). Children and implicated actors within social worlds/arenas maps: Reconsidering situational analysis from a childhood studies perspective [47 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(2), Art. 28, https://dx.doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.2.4089.