Volume 25, No. 1, Art. 4 – January 2024

Multiple Ways of Seeing. Reflections on an Image-Based Q Study on Reconciliation in Colombia

Anika Oettler, Ilona Stahl, Luisa Betancourt Macuase & Myriell Fusser

Abstract: Q methodology was created as a means to explore and map subjective viewpoints in a systematic, relational and holistic manner. In this paper, we discuss Q methodology as a promising hybrid approach and present methodological takeaways from an online Q study on the meanings of reconciliation in Colombia, based on data obtained in 2021. Q is a method of capturing subjectivity that conveys an aura of objectivity, because researchers seldom explicitly engage subjectivity We provide a brief overview of our research project, showcase some results, and offer a lens through which to reflect on the entanglement of qualitative and quantitative moments in Q methodology. We spell out its interpretive layers, highlighting the role of subjectivity in two key phases of the research: the design of the study (image-based Q items) and the interpretive process (factor analysis). Although the quantitative moments of Q are seductive in their promise of objective factor analytical measurement, we argue that Q requires researchers to practice reflexivity and to explicitly engage with their subjectivity.

Key words: Q methodology; Q sorts, subjectivity; hybrids; mixed methods research; image-based research; reconciliation; Colombia

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Background: Addressing the Meanings of Reconciliation in Colombia

3. The Study

3.1 Creating the Q item set

3.2 Designing the task

3.3 Conducting research in pandemic conditions

3.4 The results: Shared and controversial viewpoints on reconciliation in Colombia

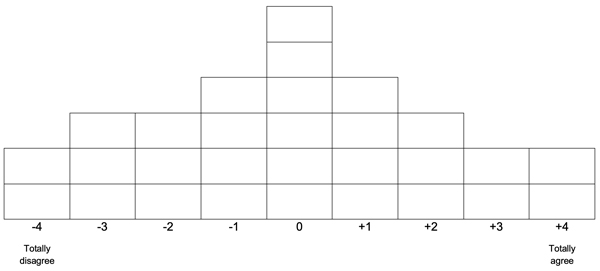

4. Discussion: Two Moments of Interpretative Subjectivity

4.1 Creating a Q set and the conceptual space around images

4.2 Subjective and intersubjective dynamics in factor analysis

4.2.1 Factor extraction

4.2.2 Factor interpretation

4.3 Recommendations for image-based Q methodological studies

5. Conclusions

It is through concepts and narratives that we make sense of our world. But how does an individual's point of view—attached to a complex set of beliefs, identities, experiences and worldviews—intersect with other points of view? In his famous and influential book "Political Subjectivity. Applications of Q Methodology in Political Science," BROWN (1980) described Q technique and the related methodology as a systematic and reliable means of examining human subjectivity. Based on a social constructionist and abductive logic, Q methodology (Q) brings together the strengths of quantitative and qualitative research, "embedding one within the other" (CRESWELL & PLANO CLARK, 2011, p.5). It is an inherently mixed methods approach that combines strong qualitative underpinnings with quantitative factor analysis (MOLENVELD, 2020, pp.334-335; RAMLO, 2022a, p.237). Q methodological studies gravitate around a specific procedure whereby participants place items (usually statements) in a rank order, e.g., from I strongly agree (+5) to I strongly disagree (-5). While the sorting process is subjective and self-referential, the sorted items (Q sorts) take the form of quantitative data (RAMLO & NEWMAN, 2011, pp.178-179). They are correlated and grouped in a multidimensional space whose axes are subsequently rotated in order to find the best "vantage point from which the relationships [between Q sorts] are observed" (BROWN, 1980, p.230). Factor rotation and factor interpretation (which considers additional qualitative and quantitative data such as semi-structured interviews and socio-demographic questionnaires) are shaped by a logic of intuition, discovery, and abduction (ibid.; see also WATTS & STENNER, 2012, p.46). [1]

Taking up some of the issues raised in the recent FQS special issue "Mixed Methods and Multimethod Social Research—Current Applications and Future Directions" (KNAPPERTSBUSCH, SCHREIER, BURZAN & FIELDING, 2023a), we discuss Q methodology as a hybrid approach. As the editors highlighted, hybrids are a "distinct category within—or in addition to—mixed methods" (KNAPPERTSBUSCH, SCHREIER, BURZAN & FIELDING, 2023b, §6). While quantitative data (variables and their values) essentially differ from qualitative data (multiple and overlapping meanings) (SCHOONENBOOM, 2023, §51), Q methodology involves a unique hybrid procedure. On the following pages, we will delve into the interwoven and entwined fabric of Q and its quantitative and qualitative components. These are "so closely 'packed' as to be practically indistinguishable" (FIELDING & SCHREIER, 2001, §33). Moreover, Q methodology is a mixed method in a dialogic sense. As GREENE (2007, p.20) put it, mixed methods research refers to "multiple ways of seeing and hearing, multiple ways of making sense of the social world, and multiple standpoints on what is important and to be valued and cherished." [2]

This quote is also perfectly applicable to our image-based Q methodological study on reconciliation in Colombia. The country, plagued by armed conflict for many decades, has a rich history of local peacebuilding that rests on discursive foundations like reconciliation. But as this term means different things to different people in different contexts (OETTLER & RETTBERG, 2019), we need a systematic approach to single out and group subjective views in a holistic manner. Q methodology serves this purpose. In Q, factors are based on groupings of participants (rather than variables). [3]

In this article, we address methodological issues that arose from an online Q methodological study in 2021 on the meanings of reconciliation in Colombia. As mentioned above, Q methodology is a method for studying participant subjectivity that embraces constructivism and the logic of abduction. While it is a reflexive approach for studying participant subjectivity, it is striking that most Q methodological researchers do not reveal much of what is taking place inside the "black box" of their studies, and factorial analysis "still retains an aura of the spectacular" (BROWN, Q listserv, July 17, 2022). We embrace the idea of reflexivity and the recommendation to "Q researchers to describe their view regarding subjectivity" (LUNDBERG, FRASCHINI & ALIANI, 2022, p.4524). Therefore, we make explicit how researcher subjectivity influenced the process of exploring participant subjectivity. We will show how our research team constantly paid "critical attention to personal, interpersonal, methodological, and contextual factors" (OLMOS-VEGA, STALMEIJER, VARPIO & KAHLKE, 2023, p.242) that influenced the multiple ways of seeing our data. We highlight two moments of subjectivity related to the design of the study (image-based Q item set) and the interpretative process (factor analysis). We hope this article is a useful contribution to strengthening a hybrid (rather than procedural) logic of mixed method research which maintains a constant dialogue across the quantitative-qualitative continuum (RAMLO & NEWMAN, 2011), while being well aware of its subjective involvement. [4]

In the following section, we briefly introduce the topic and general background of our research project on the meanings of reconciliation in Colombia. Section 3 is dedicated to the Q methodological procedure and showcases some of our results. Based on this short description, we discuss in Section 4 the problem of subjectivity in the creation of an image-based Q item set (Section 4.1) and in factor extraction and interpretation (Section 4.2). In a methodological sense, these aspects are highly relevant not only for Q methodologists. To advance mixed methods as a reflexive approach that highlights the deeply intertwined, yet not merged nature of the qualitative and the quantitative, we should reflect more on the role of subjectivity. Therefore, in Section 4.3., we summarize the unique potential of Q methodology in this regard and turn to practical recommendations. With the brief concluding Section 5, we bring the argument back to the paradigmatic debate on hybrids in mixed methods research.1) [5]

2. Background: Addressing the Meanings of Reconciliation in Colombia

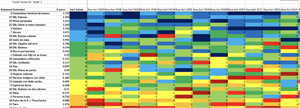

This article is concerned with key challenges we encountered in undertaking a Q methodological study on reconciliation in Colombia. In the following paragraphs, we will provide some context to encourage readers to travel with us through the troubling waters of our research. In general, our work is in line with the metaphor of the sociologist being a "hunter of myths" (ELIAS, 1984 [1970], Chapter 2). We question what we and others take for granted in daily and political life, and hope to enable a more sensitive, contextualized and fine-tuned understanding of the terms that order the social world. These terms are part of a shared but contested symbolic universe, in which signifiers are apparently and provisionally linked to signifieds (LÉVI-STRAUSS, 1987 [1950]). The term reconciliation is such a floating signifier. In academic, political, and everyday usage, it has numerous possible meanings (GIBSON, 2016; NADLER, 2012; PANKHURST, 1999), and it can be used as a flaw political rhetoric to distract from responsibility and accountability. While reconciliation has a strong normative force in peacebuilding theory and practice (LEDERACH, 1997), controversies remain, and BLOOMFIELD's (2006, p.5) observation, that "there is still no clearly agreed definition of what that term encompasses" still holds true. [6]

In our approach, we review the burgeoning literature as a point of departure. Based on the work of RETTBERG and UGARRIZA (2016) and the systematic review of an extended database of 400 articles and books, OETTLER and RETTBERG (2019) proposed an adjusted multidimensional typology of the discursive field. They highlighted that reconciliation is situated at different levels (e.g., national, intergenerational, intergroup, intrapersonal, interpersonal), that it refers to different attitudes and practices (e.g., apology, compassion, dialogue, forgiveness, harmony, recognition), and that different conditions are conceptualized as criteria for reconciliation (e.g., cessation of physical violence, assessing guilt, accountability, healing, justice, memory, identity, reparation, structural change). As demonstrated by our previous works based on surveys and focus groups (OETTLER & RETTBERG, 2019; OETTLER et al., 2018), many of these categories come into play when respondents reflect on the meanings of reconciliation. [7]

To complicate things even further, we address the complex panorama of Colombian violence that involves a long history of various armed conflicts, peace negotiations and institutionalized reconciliation efforts (DÍAZ PABÓN, 2018). While the armed confrontation between Colombia's biggest guerrilla group, the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia—Ejército del Pueblo (FARC-EP), and the Colombian government ended by peace accord in 2016, massive human rights violations are still being committed in the context of rivalry between paramilitary, insurgent and criminal armed groups among other, non-war multilevel conflicts. Understandings of reconciliation are nurtured by a variety of experiences, and they even include questions of how to deal with social exclusion and social injustice. [8]

Because consensus on the meanings of reconciliation still remains sparse and the complexities of Colombian chronic violence pose yet another challenge (OETTLER & RETTBERG, 2019), we wanted to know which discursive communities share which perspectives on reconciliation. We believed Q methodology to be the most promising tool to answer this research question: the Q sorting experience involves the active engagement with items and sorting of meaning—it is social constructivism at work. In surveys, social desirability constitutes a key challenge. For instance, most people would agree with the following twitter message of Pope FRANCIS: "Let's reconcile in order to live as beloved children, as forgiven sinners, as healed patients, as accompanied walkers,”2) 3) But what happens when respondents have to compare this statement to others such as: "If I realized that my neighbor is a paramilitary, I would not talk to him anymore" (a classic quantitative survey item in Colombia)? In contrast to quantitative surveys, the Q sorting requires participants to actively deal with a heterogeneous and complex set of stimulus items and to rank them. Q methodology is an interpretative approach to make the discursive field visible. As we will discuss in the following pages, Q methodology is usually combined with multiple data sources (Q sorts, questionnaire, semi-structured interviews) that allow for creating a complex picture which remains open to surprising, bewildering, and unexpected observations arising from the data. [9]

With the aim of familiarizing readers with the design, implementation and results of our study, the next paragraphs mirror the research process: from the initial decisions to the selection of items (Q sample) and participants (p-sample) to the questionnaires and semi-structured interviews, the data analysis, and, finally, some showcased results. Since the COVID-19 pandemic restricted fieldwork worldwide, we decided to conduct our study online. Although the sample of participants turned out to include people from diverse regions and socio-economic backgrounds (BETANCOURT MACUASE, FUSSER, OETTLER & STAHL, 2022), we could only reach people feeling confident and adept at participating in an online experiment (that requires a stable internet connection and a computer screen). This was a clear limitation of our study. We used Q Method Software, a program tailored to design and implement all steps of a web-based Q methodological study, including the creation of instructions for participants, Q item set, distribution matrix, questionnaires, instructions for semi-structured interviews, correlation and rotation methods, and export of data in CSV form. In addition, we used Ken Q Analysis, a free web application for analyzing Q methodological data. Although online surveys have some advantages (low cost, people can participate from everywhere and can independently decide about their time, no influence by interviewers), there are also severe limitations such as low response rates, interruptions and drop-outs of respondents, as well as limitations regarding the participation of social groups without access to internet and computers. A difficult challenge in designing online surveys derives from the fact that respondents complete them by themselves. This has two implications: when the survey is too long, the drop-out rate is high. When the survey is boring, the drop-out rate may be even higher. Therefore, our aim was to create a stimulating, motivating and inspiring online survey experience. Not too long, not boring. [10]

The first key step in the elaboration of a Q study is the creation of a Q sample through the identification of a concourse that contains the relevant aspects of the media, academic and daily discourses about the subject under study (VAN EXEL & GRAAF, 2005, p.4). STEPHENSON (1986) used the term concourse that usually refers to a public space as the site of spontaneous encounters and meetings as well as of massive congregations. According to him, each personal opinion is an update, selection, composition and articulation of meaning that can be found in this public square. A concourse is a space that is dynamically established through communication (KARASU & PEKER, 2019, p.41), and that is condensed into a Q sample composed of items that do not represent facts but opinions (VAN EXEL & GRAAF, 2005, p.4). Items are typically statements (or sentences), but objects, images, photographs, drawings, works of art, or even music can also be used (BROWN, 1993, p.95; VAN EXEL & GRAAF, 2005, p.4). Opinions about how many items the final Q sample should contain vary widely, ranging from a minimum of ten to a maximum of 140 items (DZIOPA & AHERN, 2011, p.42). Above all, however, the final Q sample should contain as many items as needed in order to be a "representative condensation of information," although it "can never really be complete (as there is always 'something else' that might potentially be said)" (WATTS & STENNER, 2005, p.75). [11]

There is considerable interpretative space around both statements and images, and although it is difficult to capture the essence of something by an image, the exposure to images is good for inspiring us to re-examine our attitudes and beliefs. In contrast to quantitative approaches, in Q methodology the items' meanings are not predefined by the researchers but interpreted by the Q sorters (the participants) themselves in the very moment of the Q sorting (RAMLO, 2016, p.33). Although adding a challenging endeavor to the interpretative part of the analysis, the multilayered meanings of images are an enriching source for subjective expressions. We hoped that since we had to do the study online and asynchronously, an image-based survey would prevent boredom, encourage and inspire participation, and make it easier for some social groups to engage. In the preparatory phase of our study, we reduced a concourse of 178 images to a Q item set of 30 images that condensed the variety of understandings regarding reconciliation in Colombia. Drawing on the above-mentioned typology (OETTLER & RETTBERG, 2019), the Q item set was designed to represent micro and macro dimensions of reconciliation as well as the plurality of social groups in Colombia and actors in the armed conflict. The images included pictogram drawings as well as photographs, showing, to mention but a few examples, a peace dove, people in interaction, and weapons on flowers. A table with a description and possible interpretation for each image can be found in the data repository (STAHL et al., 2022). The challenges of dealing with the conceptual space around images will be discussed in section 4.1 (see Figures 2 and 3). [12]

One of our first decisions was to use a forced distribution with nine (-4 to +4) columns. In contrast to a free distribution (WATTS & STENNER, 2012, pp.77-78), a forced distribution has fewer ranking positions in each column and takes the form of a quasi-normal distribution (VAN EXEL & GRAAF, 2005, p.6). Since "[b]oth the range and the distribution shape are arbitrary and have no effect on the subsequent statistical analysis" (BROWN, 1993, p.102), and previous experience with an unforced distribution demonstrated that participants tended to rapidly place many items at the extremes (-4 and +4), we opted for a forced distribution that prescribes two items at the extreme ranks. We hoped that a 30-Q-item-set and a Q sort continuum with nine columns (Figure 1) would not overburden participants by forcing them to make very fine distinctions between too many items and ranks. The forced distribution model is a means to encourage participants to compare items and to engage more systematically with them. However, helping participants to figure out what they have to do is a major challenge in conducting an online study. Even though we provided participants with fairly self-explanatory instructions and produced a short video tutorial with step-by-step instructions, we do not know how many participants rather just curiously clicked to look what happens, instead of actually following the instructions.

Figure 1: Q sort distribution [13]

Following the standard Q procedure (WATTS & STENNER, 2012), participants were instructed to pre-sort items in three categories: items they consider representative for reconciliation in Colombia, items they do not consider representative for reconciliation in Colombia, and items they are undecided, neutral or doubtful about (BROWN, 1993, p.102; VAN EXEL & GRAAF, 2005, p.7). In the second step, the participants were asked to distribute the pre-sorted items on the distribution (BROWN, 1993, p.102). Following the Q sorting, they were then asked to fill out a short questionnaire, and to answer five questions about their experience during the Q sorting and their opinion on the future of reconciliation in Colombia (p.106; see also WATTS & STENNER, 2005, p.78). They could either leave written comments in Q Method Software or send voice messages via WhatsApp. [14]

3.3 Conducting research in pandemic conditions

In Q methodological studies, participants are selected specifically—not randomly—and form the "p-set" (BROWN, 1980, p.192). In contrast to common factor analysis, in Q methodology persons have the status of variables and thus, participants must be chosen who "have viewpoints pertinent to the problem under investigation" (p.194). Thus, while it is important that there are enough participants to cover all perspectives on the research topic, it is not necessary to have a representative sample (p.192; see also YANG, 2016, p.45). As for items in Q samples, there are different opinions on how many participants should be part of the p-set. For example, WATTS and STENNER recommended "to stick to a number of participants that is less than the number of items" (2012, p.73, emphasis added), STAINTON ROGERS (1995, cited in WATTS & STENNER, 2012, p.73) suggested considering 40-60 participants and BROWN (1980, p.104) argued that p-sets "rarely exceed 50." However, there are several studies with considerably more participants (EPPINGA, MIJTS & SANTOS, 2022; HAMMAMI, HAMMAMI, KAWADRY & ALVI, 2022; MORINIÈRE & HAMZA, 2012; RAMLO, 2021; YANG, 2016). The key component of our sampling strategy was to capture a diverse set of participants, and the highest possible level of diversity regarding societal experiences in the context of multi-layered and enduring violence in Colombia (OETTLER & RETTBERG, 2019). The initial non-probability snowball sampling technique, contacting our networks, and distributing a flyer and invitation link, was complemented by a stage of more purposive sampling, trying to connect to rather hard-to-reach groups such as entrepreneurs, members of the military and ex-guerrilla fighters as well as those marginalized due to class, ethnicity, and geographic location. The survey was open from October to mid-December 2021, 400 people started the process of Q sorting, and 198 completed it. [15]

3.4 The results: Shared and controversial viewpoints on reconciliation in Colombia

In contrast to the established Q data analysis approach, our team embarked on two separate journeys during the first phase of data analysis, with one group dedicated to a grounded-theory-inspired interpretation of all comments and the other undertaking factor analysis. The rationale was two-fold: first, we wanted to analyze all comments and not just those connected to Q sorts that were assigned to a factor. Second, and more importantly, we felt that running a separate qualitative analysis of all comments would allow for more nuanced and comprehensive conclusions. Aiming to remain open for discoveries and different readings of our data, we took one key aspect from grounded theory methodology: initial coding (CHARMAZ, 2006, pp.42ff.). Although not being part of the standard Q procedure, the grounded-theory inspired analysis of all comments and the strict separation between these teams proved to be an excellent decision, because it added another layer of reflexivity, and the reading and interpretation of all comments did not influence factor analysis and vice versa. In mathematical terms, performing various factor analyses produced several acceptable solutions from two to eight factors. Identifying the most satisfactory solution, a five-factor solution, was a complex process which we will discuss in greater detail in Section 4.2. [16]

Roughly summarized, our key finding is that there are different discursive communities on reconciliation in Colombia which are characterized by a significant discursive overlap as well as opposing or complementary perspectives. The general picture revealed by the 198 Q sorts highlights the predominance of generational transmission and the interaction between individuals or groups. The comments indicate that the vast majority of the images were perceived as important aspects of reconciliation. A difficulty arose in distinguishing the normative (what reconciliation should be) from the evaluation of the current situation (what is perceived as the reality of the country). At the time of our survey, the different perspectives on reconciliation were closely linked to the perception of social reality and the evaluation of politics. [17]

The Q sorts assigned to factor A are characterized by optimism about the peace process and connect reconciliation to the holistic project of the 2016 peace agreement. This perspective prescribes socio-political conditions and calls for a wide and complex understanding of reconciliation that can be described as "structural reconciliation" in the sense of integral peace (BIRKE DANIELS & KURTENBACH, 2021; GONZÁLEZ GONZÁLEZ, 2020). In Factor B, reconciliation means national reconstruction, restoration of relations between antagonists, and what is visible is a strong desire for the construction of a united nation among all Colombians. On the contrary to the holistic idea of reconciliation being condensed in Factor A, the main distinguishing feature of Factor C is the absence of violence as a minimum requirement for a reconciliation process. Factor D is centered around a rather pessimistic view on reconciliation that is influenced by the disappointment with politics and with the implementation of the peace accords. In Factor E, reconciliation is rather framed as an everyday practice that is connected to respect, empathy, and interaction. In sum, the five perspectives (factors) on reconciliation mainly differ regarding the evaluation of the implementation of the 2016 peace agreements. What the comments and interviews reveal is that optimistic, pessimistic, and neutral views regarding the future of reconciliation are connected to the attribution of responsibilities. [18]

As expected, our Q analysis confirms that reconciliation is a multidimensional phenomenon and a "composite idea" (RETTBERG, UGARRIZA, ACOSTA & GARCÍA, 2021, p.10). In fact, it is reconciliations, in plural. While interpersonal dynamics matter to most respondents, there is also a strong notion of political reconciliation, linked to the peace process and the political responsibility for generating the structural preconditions for reconciliation. These are hardly surprising conclusions, but still very relevant because they demonstrate the importance of a context-sensitive conceptualization of reconciliation. Our selection of 30 images covered a multitude of possible meanings and dimensions of reconciliation, and 198 people placed them on a scale of -4 to +4, according to their perception of normative relevance or sense of their real existence. The detailed analysis of correlations within and between the factors (always taking into account socio-demographic data and the comments of the people assigned to each factor) revealed that the controversial points have to do with the perception of the implementation of the peace agreements, which are key aspects of political reconciliation (GIBSON, 2016; MADDISON, 2015; NORDQUIST, 2017; PHILPOTT, 2009; SCHAAP, 2005, 2016; VERDEJA, 2012). It is a well-established conclusion that "reconciliation does not occur in a vacuum" (RETTBERG et al., 2021, p.14), but that security and well-being are crucial to achieving it. In a sense, our study helps to explain the post-electoral atmosphere of 2022, with an overall consensus on the need to guarantee security and to pay attention to structural problems and the implementation of the 2016 peace accord. [19]

4. Discussion: Two Moments of Interpretative Subjectivity

4.1 Creating a Q set and the conceptual space around images

The creation of a Q item set lies at the heart of a Q methodological study. As mentioned above, we took a visual route, and this revealed the problem of researcher bias in a particularly nuanced way. WATTS and STENNER (2012, p.57) highlighted: "Pictures and the like may seem a more difficult medium to interpret [...], but this is really not a problem." Although not a problem per se, our experience is that an image-based Q set design is full of challenges testing us at every stage of the research process. Images do not constitute neutral windows to the world, they are artifacts that interact with the viewers, with their composition, contrast, color and perspective shaping, suggesting and reinforcing meaning. They operate within frames, and they have frames. Some things are depicted, and others are not. As we will describe in this and the following section, we constantly struggled with the interpretative usage of images. [20]

There are different rationales for an image-based Q set design. "If you are interested in ascertaining views about a new range of chairs, for examples, pictures of the chairs would probably work much better than even the most articulate linguistic description" (ibid.). It is interesting that WATTS and STENNER referred to chairs, which have been a prominent theme in philosophical reasoning for centuries, for instance, in phenomenological debates on experience and the perception of material beings (McDANIEL, 2013). We see the front of a chair and presume to know what the back looks like. In his famous "One and Three Chairs" (1965), artist Joseph KOSUTH4) presented a chair, together with a photograph of that same chair and a dictionary entry of chair. KOSUTH's work is an invitation to think about the relation between the signifier and the signified, the object and the visual or linguistic representation, and it brings up another aspect that calls for constant reflection. It is by experience or convention that we are able to make meaning of what we look at. While some may think of a bourgeois wooden chair, others will have a practical and affordable foldable chair in mind. Short people may consider it a too-high seat chair, wheelchair users may describe it as an unstable chair, and those who have never used a chair may think of a wooden object with a platform and four legs. While these interpretations mirror the social and cultural worlds of the viewers, they also point to KOSUTH's positionality. Why did he depict this chair? And not a white monobloc plastic chair? Wouldn't a non-foldable chair be more representative for chair? As this example demonstrates, there is ample space concerning pictures for personal associations and alternative interpretation. Obviously, depicting reconciliation and its various dimensions is a more complicated endeavor than illustrating a chair. Generating a concise and balanced Q item set, covering all relevant aspects of the concourse, was a time-consuming effort that lasted for several months. We faced five major challenges: [21]

First and foremost, there were ethical considerations. The decision to create an image-based Q item set immediately generated ethical dilemmas, related to the principle of avoiding re-traumatization of participants. How could we depict the dimensions of reconciliation without triggering painful memories or re-traumatization? For instance, how to deal with massacres, one of the most urgent dimensions of mass violence the Colombian society has to deal with? What does this practice mean for the prospects of reconciliation in Colombia? And how to depict them without causing harm? Second, the images and the selection of images as a whole ought to reflect every portion of meaning that might matter to our participants. Coming back to KOSUTH's installation, our point of departure for selecting images of chair was a myriad of dictionary entries of chair. In our previous work, we had been breaking down the discourse on reconciliation into a detailed typology (OETTLER & RETTBERG, 2019; RETTBERG & UGARRIZA, 2016). This typology included key dimensions and aspects that define the academic discourse on reconciliation. Third, a balanced appreciation of reconciliation in Colombia had to represent diversity in terms of gender, class, race, ethnicity, sexuality, age, and geographic location without falling into stereotypical depictions. The worldwide web is full of stereotypical images and icons, for instance, the results of a Google image search for "reconciliation couple" include few non-white couples, but rarely any non-middle-class, non-urban and no indigenous couples. Creating a non-biased Q item set is always a challenge, but images immediately and clearly show the difficulty of balanced representation. In verbal statements, the bias is hidden behind the letters. Fourth, how to deal with the complexity of the specific political and postcolonial constellation and the blurring lines between perpetrators, bystanders, beneficiaries, and victims in a society facing enduring violence? How to depict individual and collective responsibility for human rights and acts of violence? Should we present individual and recognizable actors? [22]

While the previous four challenges are of ethical nature, the fifth challenge is related to pragmatic considerations: obtaining image permissions. We did not want to make the mistake to use an image without the proper right to do so. Understanding Colombian, German, and global principles of copyright permissions and attribution for pictures that have a Creative Common license was a time-consuming activity. Our solution to these challenges was to give much room to express, interpret and exchange ideas. We conducted a virtual workshop with our German and Colombian cooperation partners as well as a pretest with Colombian students from diverse disciplines. We created a comprehensive selection of 178 images, considering the multidimensional typology of reconciliation (OETTLER & RETTBERG, 2019; RETTBERG & UGARRIZA, 2016), the results of a qualitative pilot study on reconciliation (OETTLER et al., 2018), and a variety of media sources. It turned out to be extremely valuable that our team was not only interdisciplinary, but also binational. This made it possible to alternate between closeness and distance, to question our views and to delineate perspectives. However, we sometimes entered ethically difficult terrain and often could not realize our ideas because of copyright issues. [23]

After many reflective loops and intense discussions that helped us to generate decisions, we agreed on a Q set comprised of 30 images, photographs and drawings, that vary in level of abstraction and composition complexity. We hoped to have achieved our main goal: the Q item set as a whole should be balanced, concise, and should cover the multidimensionality of reconciliation as well as the diversity and complexity of Colombian society and politics. Coming back to KOSUTH's work, our Q item set included pictures of a chair in diverse settings, which made the connections between the signifier and the signified even fuzzier. There were some images that turned out to be easily decodable for viewers, others contained more and ambiguous elements. Our Q item set included an iconic translation of a metaphor, putting oneself in another's shoes (which had been a leitmotif in previous focus group discussions on reconciliation, (OETTLER et al., 2018). It was not an easy task to create a visual representation, but the result (Figure 2) turned out to be easily decodable for viewers. But how to depict public remembrance of mass violence, which is discussed as a key dimension of reconciliation? After discussing many alternatives, we opted for including a photograph of a public act of commemoration, a kind of public art installation with speakers in the background (Figure 3). This image was closely tied to the public imagery of the armed confrontation, and it turned out that some respondents associated militarization rather than commemoration. This example testifies to the overall challenge: we cannot predict what meanings the participants will draw from the items we present to them.

Figure 2: Putting oneself in another's shoes (source: Anika OETTLER)

Figure 3: Public remembrance of mass violence (source: Anika OETTLER) [24]

4.2 Subjective and intersubjective dynamics in factor analysis

It is beyond the scope and intent of this article to provide a comprehensive assessment of Q methodology. As described above, it is a methodological approach that merges quantitative and qualitative moments (RAMLO, 2016), which is specifically the case in the factor analytical part of the methodology. In the following paragraphs, we will discuss how intersubjective dynamics operated within the black box of factor analysis, which navigates between running mathematical processes and inspecting diverse holistic solutions. There are numerous qualitative stages of interpretation in the search for patterns of similarity in the viewpoints of the participants, a process which includes intercorrelating all gathered Q sorts, extracting portions of common ground from the data matrix (factor extraction), measuring the strength of factors (eigenvalues and variance), deciding on the number of factors to be extracted, identifying different viewpoints on the data matrix as a whole (factor rotation) and factor interpretation. [25]

What is presented in most Q methodological studies is the crib sheet that contains the items which are ranked higher and lower than in any other of the study factors, and the highest and lowest ranked items in the so-called factor array or epitomizing Q sort (which is a condensation of what the "100% or perfectly loading Q sort might actually look like" (WATTS & STENNER, 2012, p.141)). Crib sheets, however, portray a mathematically derived ideal type, and we constantly struggled with making sense of the variation of Q sorts around the averages (Figure 4). We will now offer an account of how we tried to find a solution for the difficult problem of protecting our solution against too much subjective distortion. [26]

Before moving to factor interpretation, we would like to spend some words on factor extraction. While the positivist idea often prevails that factor extraction should be mainly based on mathematical decisions, quantitative rationales, and statistical criteria, we rather agree with those emphasizing its mixed-method-character and the advantages of qualitative judgments while exploring different factor-solutions (RAMLO, 2022b, pp.202-205; RAMLO & NEWMAN, 2011). Using qualitative approaches implies the possibility to include knowledge about the context, the situation, or the participants (RAMLO, 2015, p.77, 2022b, p.205). [27]

In both our pilot study on dialogue and our current study on reconciliation, we could not simply rely on the statistical criteria5) that are usually applied in order to decide for a certain number of factors. While in the dialogue project these criteria suggested a solution of only one or two factors, in the project on reconciliation all criteria, except the scree test6), were fulfilled no matter how many factors we would have extracted. It is not necessary to go into detail of the mathematical procedures, but we should not ignore the complexity at hand. In the project on reconciliation, we used the web application Ken-Q Analysis to examine different solutions (two to eight factors) with Centroid Factor Analysis (CFA) and the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) solution (eight factors), applying Varimax rotation with different significance levels (p<0.001; p<0.01; p<0.05). Following that, we checked the correlations between the factors in all these solutions. We ended up with a complex Excel sheet that contained many details and was difficult to navigate. Since all statistical criteria were fulfilled7), we first decided to rely on the correlations between the factors and had a look at the PCA solution with eight factors and Varimax rotation (p<0.05) since this was the solution with the weakest correlations between the factors8).

Figure 4: Factor scores. Please click here for an enlarged version of Figure 4. [28]

What does it mean to have a solution? Figure 4 illustrates the complexity at hand. Every available Q software calculates correlations and suggests mathematically reasonable solutions. For each factor a so-called factor array is calculated, which indicates how the items were typically rated in the respective factor solution (see column "Sort Values," Figure 4). Factor arrays are often displayed in form of a Q sort and show what a Q sort would look like if the participants placed the items exactly the same way. Q sorts that are mathematically similar to the factor array are assigned to the respective factor (see as an example the columns on the right side of column "Sort Values," Figure 4). The challenge is to decide whether a factor solution that makes mathematical sense actually makes sense. A program calculates correlations but has no idea about the meaning of the items. [29]

In our project, the best mathematical solution (PCA solution with eight factors and Varimax rotation [p<0.05]) was not the best solution: when we had a closer look at the factor arrays of this solution, we were not convinced by what we saw. It was hard to make sense of the typical arrays of the factors and the respective Q sorts. And we realized that we might be biased if we only aim to find differences among the solutions. Why should our factors be clearly separable and different? We had to recognize that, even though there were different perspectives and opinions, there was a high degree of consensus. What a closer look at means and standard deviations of all items revealed was a high degree of consensus on interpersonal and generational aspects of reconciliation, while dissent seemed to be connected to opinions on the Colombian peace process. This was a powerful assumption that guided our analysis. Thus, we decided to examine the solutions with five, six and seven factors in the same way. The five-factor-solution seemed to be most promising, which is what we finally decided on. The reasons were mainly qualitative, because we recognized patterns that made sense and contained an accurate and distinguishable factor profile. A quantitative reason was that correlations between the factors of a less-than-five factor solution were too high. The lower the number of factors, the higher the correlations between them, and the more difficult it was to see the differences. [30]

In conclusion, even though the above-mentioned mathematical criteria seem to be helpful and easy to apply, we should not and sometimes even cannot rely only on statistical criteria. This also implies that researchers must become familiar with their data during the analytical process, and in our case, this was much more time-consuming than expected. It took us a lot of time and effort to review all the factors of all the solutions (8+7+6+5=26). However, this is not lost time since it provides the positive side-effect of getting familiar with the data. [31]

In this part, we will finally shed light on the black box of factor interpretation. Since there is no strict or clear strategy for interpreting factors (BROWN, 1980, p.247), we will describe our interpretation strategy in detail as well as the challenges we faced during the interpretation process. The central objective of Q methodology is to study subjectivity. With the creation of factors, researchers seek to simplify the data creating "a finite number of perspectives" (RAMLO, 2022b, p.206) based on "shared feelings and common ground" (STENNER, 2022, p.88). Hence, in factor interpretation, patterns that are shared in a group of similar sorts are to be explained (RAMLO, 2022b, p.207). [32]

Usually, the factor arrays are the basis for interpretation. As mentioned above, a factor array is shaped like a Q sort and represents a typical view on a factor, i.e., it would correlate by a hundred percent on the factor (VAN EXEL & GRAAF, 2005, p.9). In the present study, looking at a factor array means facing 30 pictures, and in other studies, it can be even more Q items. Thus, in order not to get overwhelmed, WATTS and STENNER (2012, pp.150-156) recommend to use the crib sheet that offers a reasoned and structured procedure highlighting not only the positive and negative extremes, but also the distinguishing items that have a significantly higher or a significantly lower factor score than in any other factor9). We started our interpretation process by formulating assumptions on the basis of the highlighted images. Next, we had a look at the images that were not highlighted by the crib sheet method with the objective of confirming or adapting our assumptions. Furthermore, for a deeper understanding we compared the factor arrays to the Q sorts that were assigned to the respective factor. In the next step, we contrasted these assumptions with the comments and the socio-demographic data contributed by the participants who completed the Q sorts assigned to this factor, which serves as "ex-post verification of the interpretation, and as illustration material" (VAN EXEL & GRAAF, 2005, p.10). [33]

This might sound very clear and simple, but we—the researchers—have to keep in mind, that factor arrays are just artificial constructs that are based on similar but sometimes also very different Q sorts. In order to compare the factor arrays with the Q sorts assigned to the respective factor, we colored a table (Figure 4). The first colored column on the left shows the sort values as in the factor array. The following columns show the actual values as they were assigned by the participants during their Q sorting process. The respective Q sorts show a tendency that is similar to the sort values of the factor array, but some also differ a lot. [34]

Now making things even more complicated, researchers must keep in mind two aspects regarding the idea that Q sorting makes subjectivity operant. First, we cannot fully assess the participants' self-reflection that is connected to their sorting decisions (ROBBINS & KRUEGER, 2000, p.644). Second, Q sorting takes place at a specific time and in a specific situation. STENNER (2022, pp.87-88) remarks:

"A completed Q sort is poorly understood as a 'representation' of what a participant takes their enduring and pre-existing view to be. [...] The Q set obviously has the potential to be sorted in many ways, and what the Q sorter does is to sort them in just one way: their way of doing it, here and now. I would say that the Q sorter actualizes or makes actual the potential of the Q set. To repeat, this is not a 'representation' of a view they hold elsewhere, but a concrete and feeling based act of preference: a construction they enact in the now, in a concrete setting which naturally includes certain spoken and unspoken demands." [35]

This shows that even though in Q methodology, quantitative measures and statistics help to structure our data, the main and major part of it is qualitative in nature (MOLENVELD, 2020, pp.334-335). Q methodology requires dedication and profound insights into the data. [36]

Adding even more complexity but also interpretative depth to our case, we were challenged by the interpretation of images. In contrast to conventional quantitative research, where fixed meanings and operational definitions are assumed for items, the Q sorting process is self-referential and the participants give meaning and significance to the items (RAMLO & NEWMAN, 2011, p.178), "rendering a posteriori interpretation inescapable" (BROWN, 2008, p.701). As mentioned above, we discussed the Q sample for a long time and intended to choose images with a clear message. However, during the interpretation we realized that as well as our participants interpreted the images differently, also in our team we suddenly had different perspectives on the images and different ideas on how to interpret the factors. One might think that the usage of statements instead of images would prevent multiple interpretations of Q items. However, in our project on dialogue in Colombia, we faced similar challenges. For example, with the statement "Dialogue is a tinto [Colombian term for a cup of coffee]" we intended to show a wider and indigenous-inspired perspective on dialogue. While some participants recognized having a cup of coffee as a dialogic situation, others could not make sense of this statement, what one participant expressed as follows: "A coffee does not speak." [37]

Coming back to the examples introduced above: A photograph of a chair may not be decoded as a chair by all viewers, and some may not relate the picture to the theme of the investigation, because they think of a functional object with a platform and four legs. Our Q item set included complex drawings that were easily decoded by the participants of our pretests (Figure 3) just as photographs and drawings allowed many possible interpretations. This demonstrates that Q methodology relies on nuanced, reflexive and collaborative interpretation. What if a factor includes a distinguishing item such as Figure 3—how can we be sure that our interpretation does not distort the views of the participants? This was a fundamental question that accompanied us throughout the entire interpretation process. In the end, we were convinced that we had found a sensible solution after many feedback loops, but we cannot be absolutely sure that it is like this and not otherwise. [38]

4.3 Recommendations for image-based Q methodological studies

The key point to take away from our image-based Q methodological study on reconciliation in Colombia is that in Q methodology the lines between qualitative and quantitative moments are artificial, i.e., there is a qualitative momentum in the quantitative and vice versa. Q items, and particularly Q images, do not represent predefined facts (VAN EXEL & GRAAF, 2005, p.4), but evoke subjective meanings (RAMLO, 2016, p.33). Researchers must rely on subjective views when choosing the images for the final Q item set. Subsequently, when the participants sort the images, they apply their subjective view and interpretation to them. Through the sorting process, the sorted sets of images (Q sorts) become quantitative data for the following factor analytical process. But due to the subjective views that play a central role in Q sorting, Q sorts as well as the factors are not merely quantitative data. They are inherently mixed data (RAMLO, 2016) and this must be considered during factor extraction and interpretation (see Section 4.2). [39]

A key insight distilled from our image-based Q methodological study on reconciliation in Colombia is that there are qualitative underpinnings of our collection and interpretation of quantitative data and vice versa. Mixed methods research is not limited to combining (or mixing or integrating) two distinct kinds of data. On a methodological level, mixed methods research is also about recognizing the intersectional nature of the quantitative and the qualitative. In this sense, we experienced that subjectivity can challenge but also—and even more importantly—enrich the decision-making processes in mixed method approaches. Therefore, we would like to present three recommendations we consider crucial for conducting an image-based Q methodological study: [40]

First, the broad scope for interpretation that surrounds images is a challenge, but at the same time it is what makes them so special. One should not underestimate the amount of time needed for obtaining the permissions for the use of copyrighted image, as well as the time needed for discussing the meaning of images. They leave room for interpretation, not only for the participants, but also for the researchers. Interpretations tend to constantly change. Second, intersubjectivity matters. We started with individual interpretations, then shared our impressions in the team, revised our first interpretations, which were afterwards reviewed again by our teammates. From time to time, we reassigned tasks and responsibilities. The different positionalities of the team members in terms of gender, age, discipline, nationality, etc. were a necessary, but not sufficient condition to achieve a satisfactory result. We consider this multi-loop approach key for engaging with "multiple ways of seeing" (GREENE, 2007, p.20). [41]

Third, there is a need to resort to supplementary comments and interviews to nurture and deepen the interpretation (BROWN, 1980; RAMLO, 2022a; RAMLO & NEWMAN, 2011; WATTS & STENNER, 2012). We were faced with a twofold challenge to interpretative breadth and depth. Although the online survey was an appropriate mode for collecting Q data, our findings were limited by the shortness of most answers. Furthermore, many comments referred to reasons for placing images at the positive and negative extremes, as well as to images that specifically called participants' attention or were hard to understand. Yet most images were left uncommented. We had 30 images, most studies have more. One cannot talk about every image in a semi-structured interview or focus group conversation. This remains a challenge but try to have as many items commented on as possible. [42]

Q methodology is a hybrid approach that by itself transcends the boundaries between quantitative and qualitative ingredients. HITCHCOCK and ONWUEGBUZIE (2020) would probably call it an equal status crossover mixed analysis. From our perspective, it is a boundary-spanning approach that can also be described as "crystallization" (DENZIN, 2010, p.423). For those situated in a social constructivist tradition of critical inquiry, Q methodology holds great potential for advancing systematic research on the social construction of meaning while acknowledging the principles of a free-flowing interpretative process (BURKE, 2015). [43]

In this paper, we refer to and build on RAMLO's (e.g., 2015, 2016, 2022b) work by adding another transparent account of how subjectivity plays a pivotal role, especially during the design of the study (image-based Q item set) and the interpretative process (factor analysis). We hope that our reflection helps in advancing the dialogic development of Q methodology as an approach that bridges the problematic quantitative-qualitative duality by highlighting simultaneity (RAMLO, 2016, p.31). Q methodology challenges another aspect of outdated dualistic thinking. Our reflection illustrates that Q goes beyond the split between the researcher and the researched, between subject (our research team) and research topic (participants' views). Q methodology was created as a means to measure subjectivity, but our choices and interpretations are highly influenced not only by context, but by ourselves. Therefore, Q researchers are encouraged to become familiar with their data and to employ subjective judgment (RAMLO, 2015, p.83, 2022b, p.205). Q calls for a new way in our methodological thinking, and as we opted for using images as Q items, the challenge of subjectivity became even more apparent. For this reason, the detailed disclosure of our research experience is highly relevant to both Q scholars and mixed-methods social researchers: the multiple ways of seeing that we, the researchers, and our participants experienced are an illustration of what is meant by subjectivity in an inherently mixed methods research process. [44]

We would like to thank the following people and institutions, who supported us during our research project. First of all, we are grateful for the generosity of the German Foundation for Peace Research (DSF), which enabled this research project "Reconciliation in Contexts of Chronic Violence: Shared Viewpoints and Controversial Issues in Colombia" (2021-2022) at Philipps-Universität Marburg (Germany). Our special thanks go to Angelika RETTBERG for her enthusiastic and inspiring collaboration. Thanks to our team members Shari KOHLMEYER, Juan Camilo PULIDO RIVEROS, and Madeleine RUBIANO LÓPEZ for their effort and dedication, and all those who shared their insights and thoughts. Our acknowledgments go to Steven BROWN for providing ideas and practical advice, to Christopher COHRS and to Antje RÖDER for their support and advice, as well as to Sharbel LUTFALLAH of Q Method Software for the valuable technical support. Our special thanks go to those who provided us with images for our study: the great team of FESCOL, GIZ's ProPaz, The Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Coexistence and Non-Repetition (CEV), Lorena CARILLO, Museo Q, Camila ACOSTA ALZATE, and CODHES, who provided us with the photo of the mural "Leader Life" by social leaders of Bajo Cauca under the coordination of the artist Tatiana SAAVEDRA.

Betancourt Macuase, Luisa; Fusser, Myriell; Oettler, Anika & Stahl, Ilona (2022). Sentidos compartidos, sentidos controversiales: un estudio Q sobre la reconciliación en Colombia [Shared and controversial meanings: a Q study on reconciliation in Colombia] Documento de Trabajo, 8, https://www.instituto-capaz.org/un-estudio-q-sobre-la-reconciliacion-en-colombia-nuevo-documento-trabajo-capaz/ [Accessed: August 21, 2023].

Birke Daniels, Kristina & Kurtenbach, Sabine (Eds.) (2021). Los enredos de la paz [The entanglements of peace]. Bogotá: FESCOL/GIGA/GIZ, https://www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikationen/buecher/los-enredos-paz-reflexiones-alrededor-del-largo-camino-transformacion-del-conflicto-armado-en-colombia [Accessed: May 4, 2023].

Bloomfield, David (2006). On good terms: Clarifying reconciliation. Berghof-Report, 14, https://berghof-foundation.org/library/on-good-terms-clarifying-reconciliation [Accessed: April 17, 2023].

Brown, Steven R. (1980). Political subjectivity: Applications of Q methodology in political science. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, https://qmethod.org/1980/01/08/brown-1980-political-subjectivity/ [Accessed: May 4, 2023].

Brown, Steven R. (1993). A primer on Q methodology. Operant Subjectivity, 16(3/4), 91-138.

Brown, Steven R. (2008). Q methodology. In Lisa M. Given (Ed.), The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (pp.699-702). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Burke, Lydia E. C.-A. (2015). Exploiting the qualitative potential of Q methodology in a post-colonial critical discourse analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(1), 65-79, https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691501400107 [Accessed: May 4, 2023].

Charmaz, Kathy (2006). Constructing grounded theory. London: Sage.

Creswell, John W. & Plano Clark, Vicki L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Denzin, Norman K. (2010). Moments, mixed methods, and paradigm dialogs. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(6), 419-427, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410364608 [Accessed: May 4, 2023].

Díaz Pabón, Fabio A. (2018). Conflict and peace in the making: Colombia from 1948-2010. In Fabio A. Díaz Pabon (Ed.), Truth, justice and reconciliation in Colombia. Transitioning from violence (pp.15-33). London: Routledge.

Dziopa, Fiona & Ahern, Kathy (2011). A systematic literature review of the applications of Q-technique and its methodology. Methodology, 7(2), 39-55.

Elias, Norbert (1984 [1970]). What is sociology?. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Eppinga, Maarten B.; Mijts, Eric N. & Santos, Maria J. (2022). Ranking the sustainable development goals: Perceived sustainability priorities in small island states. Sustainability Science, 17, 1537-1556, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01100-7 [Accessed: May 4, 2023].

Fielding, Nigel & Schreier, Margrit (2001). Introduction: On the compatibility between qualitative and quantitative research methods. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 2(1), Art. 4, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-2.1.965 [Accessed: May 13, 2023].

Gibson, James L. (2016). The contributions of truth to reconciliation: Lessons from South Africa. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 50(3), 409-432.

González González, Fernán (2020). Más allá de la coyuntura: Entre la paz territorial y "la paz con legalidad" [Beyond the current agenda: Between territorial peace and “peace with legality”]. Bogotá: CINEP, https://www.cinep.org.co/producto/mas-alla-de-la-coyuntura/ [Accessed: May 4, 2023].

Greene, Jennifer C. (2007). Mixing methods in social inquiry. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Hammami, Muhammad; Hammami, Rakad; Kawadry, Suraya & Alvi, Syed (2022). Modeling lay people's ethical views on abortion: A Q-methodology study. Developing World Bioethics, 22(2), 67-75.

Hitchcock, John H. & Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. (2020). Developing mixed methods crossover analysis approaches. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 14(1), 63-83, https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689819841782 [Accessed: May 4, 2023].

Karasu, Mehmet & Peker, Mehmet (2019). Q methodology: History, theory and application. Turkish Psychological Articles, 22(43), 40-42.

Knappertsbusch, Felix; Schreier, Margrit; Burzan, Nicole & Fielding, Nigel (Eds.) (2023a). Mixed methods and multimethod social research: Current applications and future directions. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/issue/view/76 [Accessed: October 12, 2023].

Knappertsbusch, Felix; Schreier, Margrit; Burzan, Nicole & Fielding, Nigel (2023b). Innovative applications and future directions in mixed method social research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 22, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.4013 [Accessed: May 13, 2023].

Lederach, John P. (1997). Building peace: Sustainable reconciliation in divided societies. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1987 [1950]). Introduction to the work of Marcel Mauss. London: Routledge.

Lundberg, Adrian; Fraschini, Nicola & Aliani, Renata (2022). What is subjectivity?: Scholarly perspectives on the elephant in the room. Quality & Quantity, 4509-4529, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01565-9 [Accessed: May 4, 2023].

Maddison, Sarah (2015). Conflict transformation and reconciliation: Multi-level challenges in deeply divided societies. London: Routledge.

McDaniel, Kris (2013). Heidegger's metaphysics of material beings. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 87(2), 332-357.

Molenveld, Astrid (2020). Using Q methodology in comparative analysis. In Brainard Guy Peters & Guillaume Fontaine (Eds.), Handbook of research methods and applications in comparative policy analysis (pp.333-347). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Morinière, Lezlie C.E. & Hamza, Mohammed (2012). Environment and mobility: A view from four discourses. Ambio, 41(8), 795-807.

Nadler, Arie (2012). Intergroup reconciliation: Definitions, processes, and future directions. In Linda R. Tropp (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of intergroup conflict (pp.291-308). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nordquist, Kjell-Åke (2017). Reconciliation as politics: A concept and its practice. Eugene, OR: Pickwick.

Oettler, Anika & Rettberg, Angelika (2019). Varieties of reconciliation in violent contexts: Lessons from Colombia. Peacebuilding, 7(3), 329-352.

Oettler, Anika; Ahrends, Lena; Arnold, Wiebke; Fusser, Myriell; Gessler, Ornella; Jalali, Sonja; Jordan, Antonia; Reiter, Julian; Reuchlein, Veronika & Schell, Leonie (2018). Imaginando la reconciliación: Estudiantes de Bogotá y los múltiples caminos de la historia colombiana [Imagining reconciliation: Students from Bogotá and the pultple ways of Colombian history]. Ideas Verdes, 9, Bogotá, https://co.boell.org/es/2018/09/17/imaginando-la-reconciliacion-estudiantes-de-bogota-y-los-multiples-caminos-de-la-historia [Accessed: May 6, 2022].

Olmos-Vega, Francisco M.; Stalmeijer, Renée E.; Varpio, Lara & Kahlke, Renate (2023). A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Medical Teacher, 45(3), 41-251, https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2022.2057287 [Accessed: August 19, 2023].

Pankhurst, Donna (1999). Issues of justice and reconciliation in complex political emergencies: Conceptualising reconciliation, justice and peace. Third World Quarterly, 20(1), 239-256.

Philpott, Daniel (2009). An ethic of political reconciliation. Ethics & International Affairs, 23(4), 389-407.

Ramlo, Susan (2015). Theoretical significance in Q methodology: A qualitative approach to a mixed method. Research in the Schools, 22(1), 73-87.

Ramlo, Susan (2016). Mixed method lessons learned from 80 years of Q methodology. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 10(1), 28-45.

Ramlo, Susan (2021). The coronavirus and higher education: Faculty viewpoints about universities moving online during a worldwide pandemic. Innovative Higher Education, 46(3), 241-259, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-020-09532-8 [Accessed: May 4, 2023].

Ramlo, Susan (2022a). Mixed methods research and quantum theory: Q methodology as an exemplar for complementarity. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 16(2), 226-241.

Ramlo, Susan (2022b). A science of subjectivity. In James C. Rhoads, Dan B. Thomas & Susan E. Ramlo (Eds.), Cultivating Q methodology. Essays honoring Steven R. Brown (pp.182-216). New Jersey: BookBaby.

Ramlo, Susan & Newman, Isadore (2011). Q methodology and its position in the mixed-methods continuum. Operant Subjectivity, 34(3), 172-191.

Rettberg, Angelika & Ugarriza, Juan E. (2016). Reconciliation: A comprehensive framework for empirical analysis. Security Dialogue, 47(6), 517-540.

Rettberg, Angelika; Ugarriza, Juan E.; Acosta, Yoikza & García, Catalina (2021). Informe de profundización: La reconciliación en Colombia tras los acuerdos de paz entre el Gobierno nacional y las FARC: Análisis del barómetro de la reconciliación ACDI/VOCA 2017-2019, fase II [In-depth report: Reconciliation in Colombia after the peace accords between the national government and the FARC: Analysis of the reconciliation barometer ACDI/VOCA 2017-2019, Phase II], https://cienciassociales.uniandes.edu.co/reconciliacion/publicaciones/ [Accessed: May 4, 2023].

Robbins, Paul & Krueger, Rob (2000). Beyond bias?: The promise and limits of Q method in human geography. Professional Geographer, 52(4), 636-648.

Schaap, Andrew (2005). Political reconciliation. London: Routledge.

Schaap, Andrew (2016). Political reconciliation through a struggle for recognition?. Social & Legal Studies, 13(4), 523-540.

Schoonenboom, Judith (2023). The fundamental difference between qualitative and quantitative data in mixed methods Research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 24(1), Art. 11, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-24.1.3986 [Accessed: August 19, 2023].

Stahl, Ilona; Betancourt Macuase, Luisa; Fusser, Myriell & Oettler, Anika (2022). Reconciliation in Colombia. Forschungsdatenrepositorium data_UMR, 207, November 4, https://doi.org/10.17192/fdr-147.3 [Accessed: May 4, 2023].

Stenner, Paul (2022). Q methodology and constructivism: Some reflections on sincerity and authenticity in honour of Steven Brown. In James C. Rhoads, Dan B. Thomas & Susan E. Ramlo (Eds.), Cultivating Q methodology. Essays honoring Steven R. Brown (pp.68-91). New Jersey: BookBaby.

Stephenson, William (1986). Protoconcursus: The concourse theory of communication. Operant Subjectivity, 9(2), 37-58.

van Exel, Job & Graaf, Gjalt de (2005). Q methodology: A sneak preview, https://www.betterevaluation.org/sites/default/files/vanExel.pdf [Accessed: November 11, 2023].

Verdeja, Ernesto (2012). The elements of political reconciliation. In Alexander Keller Hirsch (Ed.), Interventions. Theorizing post-conflict reconciliation. Agonism, restitution and repair (pp.166-181). London: Routledge.

Watts, Simon & Stenner, Paul (2005). Doing Q methodology: theory, method and interpretation. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2(1), 67-91.

Watts, Simon & Stenner, Paul (2012). Doing Q methodological research: Theory, method and interpretation. London: Sage.

Yang, Yang (2016). A brief introduction to Q methodology. International Journal of Adult Vocational Education and Technology, 7(2), 42-53.

1) To the extent legally possible, we make our data available to increase the transparency of our research. The data are available in the repository data_UMR (STAHL, BETANCOURT MACUASE, FUSSER & OETTLER, 2022). The datasets include 1. descriptions and possible interpretations of the images used for this study, 2. an instructional video we produced for potential participants, 3. the socio-demographic questionnaire and corresponding descriptive statistics, 4. an overview of results of statistical tests and correlations between factors, 5. our raw data, and 6. Ken Q output with 5 factors (centroid factor analysis and varimax rotation). <back>

2) Pope Francis (@pontifex_es), February 29, 2020, https://twitter.com/Pontifex_es/status/1233731142567653378 [Accessed: October 7, 2022]. <back>

3) All translations from non-English texts are ours. <back>

4) Joseph KOSUTH: "One and Three Chairs," 1965, https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81435 [Accessed: November 3, 2023]. <back>

5) The statistical criteria that are typically used are the Kaiser-Guttman criterion, Humphrey’s Rule, Significantly Loading Q sorts with significance levels of p<0.05 and p<0.01 level and the Scree Test (BROWN, 1980, pp.219-223; WATTS & STENNER, 2012, pp.105-109). <back>

6) The scree test indicated that only two factors should be extracted. <back>

7) Except the scree test, which was only fulfilled in the two-factor solution. <back>

8) Three pairs of factors showed no correlation (r<0.05), 16 weak correlation (0.05≤r<0.2), eight moderate correlation (0.2≤r<0.5) and only one pair of factors showed strong correlation (0.57). <back>

9) For explanation of the calculation see BROWN (1980, pp.244-247). <back>

Anika OETTLER is a professor of sociology at Philipps-University, Marburg and associate researcher at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg. She has widely published on peace, collective memory and transitional justice. She is particularly interested in exploring new research practices and ways of understanding the social world.

Contact:

Prof. Dr. Anika Oettler

Institute for Sociology, Philipps-University Marburg

Ketzerbach 11, D-35037 Marburg, Germany

E-mail: oettler@staff.uni-marburg.de

Ilona STAHL, at the time of this writing, is about to complete her M.A. in peace and conflict studies at Philipps-University Marburg. Her research interests include collective memory, transitional justice, forced migration, feminist and postcolonial theories.

Contact:

Ilona Stahl, B.A.

AG Oettler, Institute for Sociology, Philipps-University Marburg

Ketzerbach 11, D-35037 Marburg, Germany

E-mail: ilonastahl@posteo.de

Luisa BETANCOURT MACUASE obtained a double degree M.A. in peace and conflict studies from Kent University and Philipps-University Marburg. Her research interests are peacebuilding, social movements, diaspora, exile and victims. Currently, she is preparing her PhD project.

Contact:

Luisa Betancourt Macuase, M.A.

AG Oettler, Institute for Sociology, Philipps-University Marburg

Ketzerbach 11, D-35037 Marburg, Germany

E-mail: macualu@gmail.com

Myriell FUSSER is a researcher at the Institute of Sociology at Philipps-University Marburg. She obtained her M.A. degree in international development studies from Philipps-University Marburg. Her research interests include collective memory, transnational migration, post-development and postcolonial theories, and conflict transformation. In her PhD project, she examines the intergenerational and transnational memory of Cuban transformations.

Contact:

Myriell Fusser, M.A.

Institute for Sociology, Philipps-University Marburg

Ketzerbach 11, D-35037 Marburg, Germany

E-mail: fusserm@staff.uni-marburg.de

Oettler, Anika; Stahl, Ilona; Betancourt Macuase, Luisa & Fusser, Myriell (2024). Multiple ways of seeing. Reflections on

an image-based Q study on reconciliation in Colombia [44 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative

Social Research, 25(1), Art. 4, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-25.1.4092.