Volume 26, No. 1, Art. 2 – January 2025

Introducing the Staged Narrative Analysis: A Comprehensive Framework to Analyze Multi-Layered and Complex Narrative Data

Kristine Andra Avram

Abstract: Building on multi-perspectival research on narratives and responsibility ascriptions in the context of (past) collective violence and repression, I have developed the staged narrative analysis (SNA) to guide the systematic examination of complex and multi-layered narrative data in various research contexts. To introduce SNA in this article, I first discuss its development and then present its two components: 1., a flexible analytical framework to consider the content, structure, and context of storytelling by breaking down the analysis of narratives into the following dimensions: narrator, moment of telling, structure, and stories; and 2., a five-stage analytical procedure to enable an in-depth analysis of individual narratives from different data sources as well as a structured comparison between and across different perspectives. When presenting each of the five stages, i.e., orientation, setting the scene, zooming in, evaluation, and contrasting, I outline the techniques used applying my own empirical data as an example. Finally, I discuss the potential applications and adaptations of the SNA in other studies.

Key words: narrative analysis; analytical framework; research strategy; methodological guidance

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Developing the Staged Narrative Analysis

3. Framing the Analysis

3.1 Narrator

3.2 Moment of telling

3.3 Structure

3.4 Stories

3.5 Responsibility

4. Proceeding Through the Five Stages

4.1 Orientation

4.2 Setting the scene

4.3 Zooming in

4.4 Evaluation

4.5 Contrasting

5. Situating the Staged Narrative Analysis

Since the "narrative turn" (GOODSON & GILL, 2011), there has been a growing interest in understanding how individuals make sense of experiences and events in a storied form. The widespread adoption of a narrative approach in the humanities and social sciences (CZARNIAWSKA, 2004) is driven by its rich insights into the "complexities of human selves, lives and relations" (SQUIRE et al., 2014a, p.111) and the diverse meaning-making processes in social, cultural, and historical contexts (SOMERS, 1994). Their appeal further stems from their potential to link the personal to the social (RIESSMAN, 2008, p.10) and to connect individuals to groups or institutions (SANDBERG, 2022). Narrative approaches thus prove particularly apt for exploring individual and societal interpretations of violent or traumatic events (BRISON 2002; PRESSER, 2013) as is evident in the expanding literature on narratives about the past (e.g., AVRAM, 2022; BERMUDEZ, 2019; WERTSCH, 2021), conflict (e.g., BACHLEITNER, 2022; COBB, 2013), war (e.g., ADLER, ENSEL & WINTLE, 2019; DIXIT, 2020), political violence (e.g., BARDALL, BJARNEGÅRD & PISCOPO, 2020; DA SILVA, 2019) and terrorism (e.g., COPELAND, 2019; HOMOLAR & RODRÍGUEZ-MERINO, 2019), or the emergence of sub-disciplines such as narrative criminology (e.g., FLEETWOOD, PRESSER, SANDBERG & UGELVIK, 2019; MARUNA & LIEM, 2021; PRESSER & SANDBERG, 2015a) and victimology (e.g., HEARTY, 2023; PEMBERTON, MULDER & AARTEN, 2019; WALKLATE, MAHER, McCULLOCH, FITZ-GIBBON & BEAVIS, 2019). [1]

With the increasing use of narrative approaches in the study of conflict and violence, there are empirical contributions that provide valuable insights into how individual and official narratives about violence differ (e.g., MITROIU, 2015), how victims of political violence cope with their experience narratively (e.g., HACKETT & ROLSTON, 2009), or how perpetrators of violence narrate their actions retrospectively (e.g., DA SILVA, 2019). Despite this wealth of empirical findings, however, there is still a relative lack of clarity about "what concrete steps [researchers] take to analyze stories" (GRAEF, DA SILVA & LEMAY-HEBERT, 2020, p.437). In methodological considerations, data collection is usually discussed more than data analysis (ROLÓN-DOW & BAILEY, 2022), whereby analytical strategies and techniques remain generally described. This is often done against the background of RIESSMAN's (2008) distinction of four modes of analysis or a further development thereof (e.g., SANDBERG, 2022), whereby thematic analyses are most frequently used, increasingly also structural analyses or a combination of these modes.1) The relative lack of analytical transparency and practically useful guides in narrative studies of violence, conflict and terrorism (GRAEF et al., 2020, p.437) contrasts with the plethora of literature that discuss and develop narrative inquiry and analytical methods across disciplines and fields (see Sections 3 and 4), pointing to a diminished dialogue on methodological approaches between narrative theories and social sciences (e.g., COPELAND, 2019). On that matter, SCHIFF, McKIM and PATRON (2017, p.xiii) noted that "the interdisciplinary ethos of the early days quietly disappeared," as the need to legitimize narrative research diminished with its proliferation in social and psychological research. With the introduction of the staged narrative analysis in this article, I wish to contribute to addressing the lack of practical guidance for analysis in these research contexts, and to strengthening the conversation between narrative theories and social sciences. [2]

The staged narrative analysis (SNA), which provides both an analytical framework and a five-stage analytical procedure, emerged in the context of two research projects between 2016 and 2022 (e.g., AVRAM, 2022). Both projects were based on a multi-perspectival narrative study I conducted in Romania to reconstruct and contrast narratives about communist repression and the violent events of December 1989 from various actor groups, including national courts as well as survivors and descendants, former regime members and state agents, experts and public figures, and university students representing the younger generation. This study and the historical events underpinning it are presented in more detail in Section 2. While such multi-perspectival studies provide the opportunity to uncover a broader range of experiences and practices and to gain a deeper understanding of the meanings attributed to violence or related meaning-making processes (ELCHEROTH, PENIC, USOOF & REICHER, 2019), they are challenging and only gradually increasing due to the scale and complexity of the data collected (e.g., AVRAM, 2022; FOSTER, HAUPT & DE BEER, 2005; JESSEE, 2017; RÍOS, 2019). To analyze the extensive data set stemming from such studies—in my case, this included court documents from five criminal trials, transcripts of interviews with 59 people, and field notes—it is necessary to employ a rigorous approach and multiple techniques. To address these needs, I developed SNA as a comprehensive yet flexible framework that is adaptable to other study and research contexts. [3]

In line with a holistic approach to narrative analysis (e.g., LIEBLICH, TUVAL-MASHIACH & ZILBER, 1998), i.e., researchers focusing on the content, structure and context of storytelling, the framework is designed to guide an in-depth analysis of individual narratives and a structured comparison between perspectives. To achieve this, in SNA, concepts and frameworks from narrative theory and the social sciences are integrated, and narratives are broken down into several dimensions—narrator, moment of telling, structure, and stories—that serve as focal points for analysis. These analytical dimensions can be adapted or supplemented based on the research design and focus. For example, in one of the two projects SNA was developed—my dissertation project, which is the focus of this article—I added the dimension of responsibility to suit my specific research lens. While this dimension may be omitted in other studies, its inclusion demonstrates the framework's flexibility. SNA also comprises a five-stage analytical procedure in which thematic, structural, and dialogic-performative modes of analysis are combined, thereby broadening the range of methods available for reconstructing and comparing narratives derived from different data sources. Distinguishing five stages of the analysis—i.e., orientation, setting the scene, zooming in, evaluation, contrasting—and outlining the techniques used at each stage with examples from my own research, the introduction of the SNA in this article provides other researchers with a comprehensive toolkit and practical guidance.2) After discussing the development of SNA (Section 2) and detailing its two components (Sections 3 and 4), I situate SNA as a novel and flexible method for analyzing narratives from multiple perspectives and various data sources, highlighting its adaptability for other studies (Section 5). [4]

2. Developing the Staged Narrative Analysis

The SNA emerged from my work in two research projects on meaning-making processes in the context of past collective violence and state repression. In 2016, I began my dissertation project, which explored how societies emerging from conflict and/or dictatorships address the issue of responsibility as they make sense of past violence and repression. Underlying is my original conceptualization of responsibility as a narrative-driven practice that foregrounds narratives as a means both to make sense of the past and to ascribe and approach responsibility through storytelling (AVRAM, 2022). Shortly after, I was a co-applicant and, between 2017 and 2022, a researcher in an externally funded project that examined whether and to what extent court proceedings and judicial narratives influence societal interpretations of past violence and repression (AVRAM, 2023; AVRAM, 2024a). Although the focus of each project varied, both were based on an in-depth case study in Romania that examined and compared diverse perspectives on state repression during the communist regime and the violent December 1989 events. The parallel work on these projects required a systematic procedure to reconstruct and contrast narratives from different perspectives and data sources while remaining open to the specific analytical interest at hand (ROLÓN-DOW & BAILEY, 2022; SQUIRE et al., 2014a). These necessities oriented the development of the SNA, which is flexible in its design and suitable for applicability to other studies beyond these two projects or the Romanian context. [5]

Romania was selected as a case study in both projects due to the lack of international participation in transitional justice processes, which is important for understanding how members of the affected societies have addressed the issue of responsibility. This lack, together with language barriers, may explain why the country is still relatively under-researched, pointing to the significant empirical contribution of both projects. Moreover, I speak Romanian and am familiar with the context, which was conducive to data collection and analysis (AVRAM, 2024b). Before elaborating on the data set and the assumptions that guided research and thus the development of SNA, I would like to delineate the Romanian context briefly. [6]

After the Second World War, Gheorghe GHEORGHIU-DEJ became the first General Secretary of the Communist Party in Romania. He introduced "neo-Stalinism" and repressed perceived "class enemies," including former government officials, military officers and party leaders, clergymen, ethnic and religious minorities and peasants who resisted forced collectivization, as well as doctors, teachers and students (DELETANT, 2019). Between 1948 and 1964, around 600,000 people were imprisoned across the country and around 100,000 died in prison (RUSU, 2015). This widespread repression was aimed at suppressing opposition and transforming society into a socialist regime, and was coordinated by the Securitate—a shorthand term for the political police and secret service of the communist era. The Securitate was founded in 1948 and played a central role in enforcing and maintaining regime control through repression, surveillance and censorship (DELETANT, 2019). [7]

Following GHEORGHIU-DEJ's death in 1965, Nicolae CEAUȘESCU succeeded and expanded the dictatorship with a pronounced cult of personality (DELETANT, 2019). Although CEAUȘESCU denounced earlier abuses by the Securitate, serious human rights violations continued, and the population was subjected to more subtle psychological terror through mass surveillance (RUSU, 2015). CEAUȘESCU's rule lasted until the violent events of December 1989, when state authorities, including the Army, Militia (civilian police) and Securitate troops, violently suppressed protests that began on December 17 in Timișoara and later in other major cities. CEAUȘESCU and his wife attempted to flee the Central Committee building in Bucharest by helicopter on December 22 but were later arrested. The shootings only gradually subsided after December 25, when the couple had been convicted and executed. Romania was the only country to exit communism violently, with more than 1,100 dead and 3,300 injured. However, after this time, there was neither a decisive break with the past nor an exchange of elites (STAN, 2013; RUSU, 2015). [8]

To uncover the broad repertoire of stories (CZARNIAWSKA, 2004) prevailing in Romania, between 2016 and 2020, I spent seven months in the country. There, I conducted archival research to collect court documents on five criminal trials between 1989 and 2016 that adjudicated communist crimes and December events. In addition, I conducted semi-structured and narrative interviews (KIM, 2016; WENGRAF, 2001) with four different groups of actors following a combination of different purposeful sampling strategies (PATTON, 2002). In concrete terms, I conducted interviews with 17 survivors and descendants (e.g., survivors of communist prisons such as Aurelia and Elena (see Section 3.1, 4.2), descendants of political prisoners, participants in the revolution or relatives of victims); 12 former members of the regime and state agents (e.g., former members of the nomenclature, Army or Securitate officers such as Marian, see Section 3.2, 4.2, 4.3); 17 experts and public figures (e.g., journalists, politicians); and 13 university students as representatives of the younger generation.3) [9]

Interviews were conducted in Romanian, starting with a brief but detailed introduction of myself and a summary of my research. I also gave interviewees the opportunity to ask me questions to "create an atmosphere conducive to 'two-way and empowering interaction'" (COHN & LYONS, 2003, p.41).4) Throughout the interview, I actively listened to the interviewees and used their own language utterances to encourage them to elaborate in detail on their experiences and perspectives (CZARNIAWSKA, 2004; GUBRIUM & HOLSTEIN, 2012) and provided space for participants to add anything they wanted at the end of the interview (BALLANTINE, 2022). While I did have an interview guide for each actor group, I mainly used it to create a handwritten outline before each meeting to familiarize myself with the questions. [10]

Each interview differed in terms of content and topics covered, as well as length. On average, the interviews with university students lasted 30 minutes and those with experts and public figures 60 minutes. In contrast, the interviews with survivors and descendants or former members of the regime and state agents lasted about two, sometimes even three to four hours. Whenever possible, I conducted follow-up interviews with the latter two groups. In total, I recorded 110 hours of interviews with 59 people. In addition, I collected 800 pages of court documents and 70 pages of field notes that cover my general thoughts, assumptions, pressing questions, memos on the interviewees and interviews as well as observations made during visits to certain events and relevant locations. Acknowledging the co-construction of meaning (JOSSELSON & HAMMACK, 2021) and the situatedness of knowledge production (HARAWAY, 1988), I also kept this field diary to track my own positioning and its influence on data collection and analysis and to comprehend the impact of intersubjectivity (AVRAM, 2024b). [11]

Given the different data sources and consideration of multiple perspectives, my fieldwork has yielded "multifaceted and complex data" (VOGL, ZARTLER, SCHMIDT & RIEDER, 2018, p.188). To avoid losing focus or myself in the data (KIM, 2016), I developed the SNA for use in both projects with the overarching aim of identifying and relating a variety of narratives. For simplicity, the following presentation of the SNA refers only to my dissertation project, in which I examined how various actor groups discussed, negotiated, or omitted responsibility through storytelling in order to understand how societies address the issue of responsibility when they make sense of the past. [12]

The project was based on the premise that individuals, social and political actors or groups, and institutions, make sense of and/or communicate (traumatic) experiences and violent events in and through narratives (e.g., BRISON, 2002; PRESSER, 2013). Narratives thus "are not only a form of describing (and communicating), but also a form of constructing and understanding reality" (BRUNER, 1991, p.5). Storytelling then marks "the transition between making sense of a situation and expressing that in a structured way to the outside world" (AUKES, BONTJE & SLINGER, 2020, §26). In the context of violence, this encompasses creating a coherent and plausible story that renders the violent events or traumatic experience comprehensible and enables or produces certain responsibility ascriptions. How we ascribe responsibility, I argued, is essentially a function of the stories we tell about violence and repression, about others and ourselves. Narratives, accordingly, are a means of both making sense of the past and ascribing responsibility (AVRAM, 2022). Building on my understanding of responsibility ascriptions as a narrative-driven practice, I developed the SNA to align with my research goals, i.e., reconstructing narratives from empirical data such as court documents and interview transcripts, analyzing how responsibility is constructed and ascribed in the telling, and comparing these narratives and responsibility ascriptions across different perspectives. [13]

SNA is consistent with an interpretive epistemology (JOSSELSON & HAMMACK, 2021) and the principle of reconstruction (ROSENTHAL, 2018), aiming to facilitate the elicitation of both explicit and implicit meanings of texts while approaching each text anew. Reconstructing narratives from empirical data is guided not by pre-existing hypotheses or predefined variables but by analytical dimensions that organize the analytical process (Section 2). SNA also aligns with a holistic approach to analysis, considering narratives in their entirety and examining both their components and relational meanings (LIEBLICH et al., 1998; ROLÓN-DOW & BAILEY, 2022). This means that data from each participant is kept intact (BEAL, 2013, p.693) and that narratives are set against the broader context of the narrator, her/his life and the moment of telling (RODRÍGUEZ-DORANS & JACOBS, 2020). Acknowledging the dialogic and dynamic nature of storytelling (CLANDININ & CONNELLY, 2000), narratives retold and presented using SNA are co-constructed (MARUNA & LIEM, 2021) and ultimately form conceptual narratives (SOMERS, 1997). Ascriptions of responsibility are embedded in these conceptual narratives, which I have condensed into the "kaleidoscopic view on responsibility" (AVRAM, 2022, p.2). [14]

Against this background, SNA emerged through my engagement with literature and in dialogue with my material. During and after my fieldwork, I went back and forth "in an iterative-recursive fashion" (SCHWARTZ-SHEA & YANOW, 2012, p.27) between my data and the analytical tools and strategies. The result is a comprehensive framework that provides, first, a flexible analytical framework to enable a holistic engagement with narratives in their context by focusing the analysis on the narrator, the moment of telling, structure, and stories. Secondly, the SNA includes a five-stage analytical procedure (i.e., orientation, setting the scene, zooming in, evaluation, and contrasting) to guide the reconstruction and analysis of narratives from multiple perspectives and different data sources. In the following, I present both components in more detail before discussing the SNA's adaptability for other studies in the last section. [15]

Analytical frameworks assist in navigating the intricacies of data by "breaking down the issue at stake into subcomponents and creating a mental model" (VOGL et al., 2018, p.179) that serves as a foundation and roadmap for both data collection and analysis. To develop the analytical framework of SNA, I brought into dialogue concepts from disparate strands of literature on narrative theory (e.g., ABBOTT, 2020; COBB, 2013; LABOV, 1972), narrative analysis (e.g., DE FINA & GEORGAKOPOULOU, 2015; GUBRIUM & HOLSTEIN, 2012; MISHLER, 1995; RIESSMAN, 2008), narrative inquiry (e.g., CLANDININ & CONNELLY, 2000; CZARNIAWSKA, 2004; KIM, 2016), narrative psychology (e.g., BRUNER, 2003; CROSSLEY, 2000, 2008; MURRAY, 2003), narrative criminology (e.g., FLEETWOOD et al., 2019; PRESSER & SANDBERG, 2015a, 2015b), and law and literature (e.g., AMSTERDAM & BRUNER, 2000; BROOKS & GEWIRTZ, 1996; HENDERSON, 2015). In addition to this cross-fertilization, I adapted the framework based on my data and field observations, adding conceptualizations that were specific to my research or expanding on existing ones. [16]

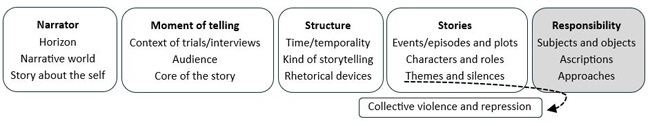

The analytical framework of SNA addresses the content, structure, and context of storytelling, focusing on the following dimensions: narrator, moment of telling, structure, and stories. These analytical dimensions, grouped around different elements (Figure 1), are located at different but interrelated levels of analysis, reflecting a comprehensive approach to analyzing narratives.5) They can serve as a basic framework for theoretical and empirical studies on both personal and public narratives in the context of violence and beyond, providing a starting point for those interested in using narrative approaches and ensuring a thorough analysis. The four analytical dimensions can also be adapted or supplemented in line with the research focus and phenomena of interest (RODRÍGUEZ-DORANS & JACOBS, 2020). For my dissertation project discussed in this article, I incorporated the dimension of responsibility into the analytical framework, as indicated in grey in the figure below. Although this dimension may be excluded from other studies, it illustrates the framework's adaptability and potential for further development. By aligning the analysis of judicial and personal narratives with these distinct but interrelated dimensions, it was possible for me to compare narratives and responsibility ascriptions from different perspectives, identifying similarities and differences between various groups of actors (AVRAM, 2022).

Figure 1: Analytical dimensions in the study of narratives (and responsibility ascriptions) [17]

The analytical framework of SNA is based on my assumptions outlined in Section 2 and is anchored in the distinction between narrative and story. Even though these two concepts are intertwined, their differentiation is essential in facilitating the analytical breakdown of empirical data (COPELAND, 2019). The structuralist division of early narratology proves advantageous in contrasting the "'what' of 'stories' (content) with the 'how and why' of 'narratives'" (SQUIRE et al., 2014b, p.25). Stories, then, are characterized by the sequence of events and the linear progression (of time), whereas narratives are characterized by the discursive organization of events (ABBOTT, 2020). In this light, I view "narratives" as the overarching structure that incorporates broader depictions of social life utilized in storytelling, while "story" refers to the speaker's account of events (WONG & BREHENY, 2018, p.246). Hence, I consider the narratives I reconstructed from interview transcripts and court documents as multi-layered, i.e., consisting of narrative threads and fragments, a multiplicity of small stories or storylines that can take different forms (BERNHARD, 2014), and several narrative accounts. [18]

Building on this, the analytical framework is intended to provide a structured approach to analyzing narratives in their entirety and in relation to the respective storytelling context as this "bounds and influences what is told—and how it is told" (JOSSELSON & HAMMACK, 2021, p.14). By dividing the analysis into key analytical dimensions to focus on both the "told" and the "telling," the analytical framework is designed to support an examination of the narrative as a whole and its constituent parts, as well as its contextualization in relation to the narrator's positioning and the moment of telling, including the co-construction of meaning between the interviewees and the interviewer (CROSSLEY, 2000). Accordingly, thematic and structural modes of analysis are integrated into SNA to help explore both the cognitive aspects ("what is said") and the linguistic structure ("how it is said") of a text. These modes of analysis are complemented with a dialogic-performative approach to consider the timing, purpose, and intended audience of a story or utterance (RIESSMAN, 2008). Such a combination of analytical approaches and modes is common in narrative research (LIEBLICH et al., 1998; RIESSMAN, 2008; SANDBERG, 2022), facilitating a nuanced understanding of narratives from different perspectives (BEAL, 2013, p.695). [19]

Before detailing the analytical framework, it is important to emphasize that each of its five dimensions has played an equally significant role in analyzing, understanding, and comparing narratives and responsibility ascriptions across different actor groups within my dissertation project. Using this framework, I reconstructed narratives from court judgments and interview transcripts, focusing on how and in which "layer" the issue of responsibility emerges, to whom it is attributed, and for what reasons. While there are overlaps between the dimensions and elements—for example, the core of the story is considered in the moment of telling but cannot be classified without the narrator, and rhetorical devices are analyzed as part of structure though they are fundamental to stories and responsibility—the focus on these dimensions was crucial to the organization of the analytical process. More specifically, prioritizing and linking at least two dimensions at each stage of the five-stage analytical procedure I outline in Section 4 was important to the analysis. [20]

While the diversity and complexity of experiences and behaviors in conflicts, dictatorships and transitions are increasingly recognized (FOSTER et al., 2005), the literature on narratives of (past) collective violence and repression tends to neglect the narrator as an analytical category. However, as my data show, interpretation and narratives about the violent past vary not only between but also within actor groups, as well as from the perspective of one and the same person at different points in time (DILLENBURGER, FARGAS & AKHONZADA, 2008; PEMBERTON et al., 2019, p.398). For example, the narratives of Aurelia and Elena, who both experienced repression as political prisoners at a young age, differ both in terms of content and structure. These differences can be understood in relation to their experiences in prison and lives after incarceration, i.e., by considering the narrator. Like GEORGAKAPOULOU (2015, p.258), I understand the narrators as a "complex entity," i.e., as "here-and-now communicators with specific roles of participation; as characters in their stories; as members of social and cultural groups; and, last but not least, as individuals with specific biographies, including habits, beliefs, hopes, desires, fears, etc." (ibid.). [21]

Taking the narrator into account makes it possible to recognize contextual nuances when reconstructing narratives and to emphasize the diversity and differences between stories. In the context of SNA, this dimension is considered by taking into account the horizon and the available narrative world. Following GADAMER (1960, p.275), who claimed that a horizon refers to "the range of vision that encompasses everything that can be seen from a particular point of view,"6) I understand it as the vantage point from which the narrator sees and narrates the world (ESIN, 2017; REICH, 2021). In narrating the world, we reveal a multiplicity of I-positions (DA SILVA, FERNÁNDEZ-NAVARRO, GONÇALVES, ROSA & SILVA, 2020), i.e., different (self) localizations in relation to the reported events, to the stories and the characters, or to the audience (BAMBERG, 1997; BAMBERG & GEORGAKOPOULOU, 2008; SCHIFFRIN, 1996). How we see, make sense of, and narrate the world, however, depends not only on who we are, what experiences we have had, and what social position we occupy, but also on the discourses and the "ultimately limited repertoire of available social, public, and cultural narratives" (SOMERS, 1994, p.614) to which we have access. Accordingly, we draw on meanings and interpretations in our personal and social environment (COPELAND, 2019; FLEETWOOD, 2015) or on what I call the available narrative world, including family stories, fictional narratives, documentary plots, (historical) figures or meta-narratives (AVRAM, 2024a). [22]

In examining the horizon of courts, I considered the political context, institutional framework, legal culture, practices, and procedures prevailing therein (SANDER, 2018) through extensive literature research and discussions with experts. When examining individuals as narrators, I primarily relied on my field notes and literature research. Additionally, the story about the self posed an analytically valuable complement to the examination of the narrator, though it should not be interpreted as an expression of narrative identity nor be confused with life stories (e.g., McADAMS, 2011).7) Instead, I understand it as a "smaller" story that reveals a sense of self (GEORGAKAPOULOU, 2015) and helps to capture contextual nuances of storytelling. The focus was on how the narrators present themselves through epistemic and agentive self-representations, anecdotes, and linguistic means in the moment of storytelling and how they are understood (or wish to be understood) (BAMBERG & GEORGAKOPOULOU, 2008).8) For example, Aurelia, a former political prisoner from the 1950s, presented herself as an accomplished intellectual who is ultimately content with her life. She framed her early imprisonment as a challenge she successfully overcame, viewing it as part of her journey toward a fulfilling life. This perspective is underscored at the end of the interview when she shared an anecdote from her high school years (see Section 4.2). In contrast, Elena, also a former political prisoner, portrayed herself as someone who has endured hardship and managed to survive, yet feels distinct from other women. This sense of difference is emphasized by her repeated use of a key phrase throughout the interview (PAMPHILION, 1999). For Elena, imprisonment is not a hurdle she overcame, but a profound rupture that continues to affect her life. [23]

Narratives are "dynamic entities; they change in subtle or radical ways as people experience and become exposed to new stories on a daily basis" (BAKER, 2006, p.3). When we tell stories, we do so at different times, to different audiences, to make different points. Narratives are not mere reflections of reality or straightforward recounts of experiences; instead, they (re)shape events and experiences as they are told and are themselves shaped "by the setting, the purpose of storytelling, and those with (or to) whom we communicate" (PRESSER & SANDBERG, 2015b, p.93). The moment of telling is thus constitutive for the content and structure of narratives and refers to the location and time of storytelling, i.e., to the context of the interview recording or the court proceedings. In analyzing judicial narratives, the context thus included the historical moment, the political power structure, and other relevant factors at the time of the trial. In examining personal narratives, I took into account the setting and progression of the interview, including political developments and current events (e.g., mass demonstrations against judicial reforms, elections). [24]

In view of the dynamic and dialogical nature of storytelling (e.g., CLANDININ & CONNELLY, 2000), using SNA implies to also consider the audience as part of the moment of telling during analysis. Regarding the criminal judgments, this referred to the public perception of the trials at the time they were held, which I traced through literature research and interviews with experts, civil parties involved in the trials, and victims' families. During the interviews, I, as a researcher, assumed the role of the audience, thereby co-constructing the participants' experiences and narratives during the interview and shaping the texts that emerged from the interview process (e.g., GUBRIUM & HOLSTEIN, 2012). For as WONG and BREHENY (2018, p.248) rightly noted, the "characteristics of the researcher and the relationship between participant and researcher also influence both the story and the way it is told." [25]

For example, during the interview, former Securitate officer Marian distinguished between two phases within the Securitate, according to which it only used repressive practices until 1968 and then—during his active time—acted in accordance with the law and professionally. He repeatedly linked this story about his former institution with references to Germany and the Stasi system in the GDR, which I attribute to my positionality. In a conversation with a researcher based in Romania, he might have used different contrast structures and thus set different frames of reference for his actions and storytelling (BISHOP, 2012). With former colleagues, on the other hand, he may never have spoken about the two phases, but only about their active period. This example illustrates the co-construction of meaning between interviewees and interviewer (CROSSLEY, 2000) and underlines the importance of researcher's reflexivity in narrative analyses (JOSSELSON & HAMMACK, 2021; KIM, 2016; ZILBER, TUVAL-MASHIACH & LIEBLICH, 2008) such as SNA. Hence, I continuously recorded my (perceived) position in relation to the interviewees in my field diary, considered references to myself in the interview transcripts and field notes, and reflected extensively on my multiple and shifting positionalities as part of my narrative research process (AVRAM, 2024b). [26]

While I was the immediate audience in interviews, the participants also had an awareness of the "'unknown' audience" (WONG & BREHENY, 2018, p.249). In this respect, the moment of telling refers to the core of the story, which can be summarized as the main message conveyed in a judgment or interview—the "how and why" of narratives (SQUIRE et al., 2014b, p.25). It is not about the "what" of stories, but about what the narrator's point is (PRESSER & SANDBERG, 2015b) or what function storytelling has for the narrator in that moment and for which purposes stories are used in social interaction (RIESMANN, 2008; SANDBERG, 2022, p.223). The core of the story is rarely explicitly stated (KIM, 2016) and instead depends on the audience's implicit understanding, underscoring the interpersonal aspect of narrative analysis (MURRAY, 2003). It is often conveyed through linguistic structures and rhetorical devices such as repetition, digressions, and interpolations, which are "introduced when details are deemed necessary for the audience to understand the message of the story" (WONG & BREHENY, 2018, p.247). Narrators may also highlight their main message using reported speech (PRESSER & SANDBERG, 2015b), as demonstrated in Section 4.2 with the example of Aurelia. [27]

Structural analysis of narratives often refers to stories and their organization and/or form with a focus on their correspondence to culturally significant "genres" (ABBOTT, 2020, p.55). While fictional or e.g., judicial narratives are often associated with a trouble that sets storytelling in motion and tend to correspond to such types (e.g., AVRAM, 2023; SARAT, 1993; UMPHREY, 1999), personal narratives do not follow a uniform structure and therefore do not lend themselves to being studied as a particular genre or narrative type (e.g., DE FINA, 2009). With SNA, the exploration of structure goes beyond identifying a genre or an overarching storyline (RIESSMAN, 2008, p.78) by focusing on how narrators use form and language, including time and temporality, storytelling mode and rhetorical devices. This type of structural analysis is in line with the distinction between narrative and story, according to which stories are set against the background of the narrative, its organization and temporal configuration (RICOEUR, 1984 [1983]). [28]

Time refers to the temporal frame of a given account of events (e.g., blurred, narrowly defined, concrete) and the temporal perspective adopted by the narrator (e.g., near vs. distant past). Temporality refers to the temporal configuration underlying or mediated by the narrative. It is a key element in narratives about political violence (COBB, 2013; COPELAND, 2019; GRAEF et al., 2020) and has recently been reflected upon more explicitly.9) Here, temporality refers both to the way in which past and present are attended to throughout storytelling (e.g., frequent alternation between past and present, focus on the present, evocation of the distant or recent past) and to the way past and present are assembled in the narrative with reference to continuities or to (social) changes (BURZAN, 2020), e.g., decline or transition. [29]

How narrators merge the past and present is linked to the storytelling mode, because when individuals or institutions narrate, storytelling does not follow the traditional (linear) pattern of a story from beginning to end, but is "staggered and fragmented" (CZARNIAWSKA, 2004, p.38). Rather than being chronologically organized, different kinds of storytelling emerge, i.e., different ways of how narrators orient their storytelling, including how they attend to the past and present or to certain characters. In my data, I identified functional (courts), polychronic (some former state agents), actor-oriented (survivors and descendants), and fragmented (university students) kinds of storytelling that serve different social functions (AVRAM, 2022). [30]

Regarding structure, I also paid attention to rhetorical devices and linguistic strategies (e.g., FOSTER et al., 2005; O'CONNOR, 2000; PRESSER & SANDBERG, 2015; WORTHAM & RHODES, 2015), including the use of active vs. passive constructions, the frequencies of nouns and verbs or the de-concretization of nouns. This enabled me, for example, to identify the narrative effects of attributing the role of the villain to the defendant(s) in judicial narratives (AVRAM, 2023). I also examined the use of metaphorical language (LAKOFF & JOHNSON, 1980), which can serve to naturalize and normalize behavior and actions (RAUSCHENBACH, STAERKLÉ & SCALIA, 2015). The example of Marian, a former Securitate officer active in the 1970s and 1980s, demonstrates how responsibility—whether personal or institutional—is managed or negotiated through such linguistic means (Section 4.3). Additionally, I examined the use of pronouns to establish or distance agency (O'CONNOR, 2000) and contrast structures to convey judgment (BISHOP, 2012). [31]

Each narrative consists of various narrative threads and stories, ranging from fragmented to fully articulated stories or something in-between (DE FINA, 2009). In my data, stories were abundant and diverse, with each narrator interweaving different stories during the storytelling. For example, the narrative of Marian included stories about Romania as a chess piece in global power politics, about the communist regime under CEAUȘESCU as a better past leading to a fatal dead end, or about patriotic professionals bearing the truth. In contrast, the narrative of Aurelia revealed stories e.g., about a personal odyssey to return home, about life under communism as "continuous nonsense," or about 21 December 1989 as a moment of hope and breaking through fear. These stories select, (re)construct, and sequence (violent) events and episodes, assign characters a function (i.e., a role), provide explanations and convey a 'moral', i.e., an account of "why things happened the way (the narrator) suggests (it to have) happened" (BAKER, 2006, p.9). [32]

In my analysis of stories, I concentrated on events, characters, plots, and themes, as detailed in the literature on the construction and analysis of narratives (e.g., ABBOTT, 2020; COBB, 2013; KIM, 2016) and illustrated in Section 4.3. regarding characters. These elements are similar in all standard stories and genres (PRESSER & SANDBERG, 2015b), including both judicial and personal narratives. Importantly, objects and abstract entities can also play active roles, drive the story forward, and serve as prototypical characters (PROPP, 1968). For example, Communism, which was publicly condemned by then President BĂSESCU in 2008 (RUSU, 2015), was portrayed in several stories as the villain responsible for the suffering of the Romanian population. To explore the overall plot, I linked events and characters with the narrative structure into a meaningful whole (BISHOP, 2012; CZARNIAWSKA, 2004; POLKINGHORNE, 1995). Here, I focused on various story forms, considering whether the story represents e.g., ascent or descent, suffering or redemption, or change or transformation (JOSSELSON & HAMMACK, 2021). [33]

Given my research interest, I engaged with violence and repression as a distinct narrative theme (SANDMAN, 2023). For this, I drew on the metaphorical representation of violence and pain as weapons and wounds as proposed by SCARRY (1985) and followed up by SARAT (1993) and COBB (2013). While judicial narratives focus on the weapon and its effect, i.e., the wound, understood as "the bodily damage that is pictured as accompanying pain" (SCARRY, 1985, p.15), violence and repression appear and function in many more ways in personal narratives. Here, I primarily looked at the portrayal of violence and repression and its explanations in terms of, for example, the (dis)connection of violence from/to context, the conflation of conflict and violence vs differentiation between these two, or the removal vs stress of human agency as a weapon. Going beyond this metaphorical representation of violence and pain as weapon and wound, narratives by survivors and descendants revealed what I call the transformative effect of the wound as a distinct narrative thread (AVRAM, 2022). [34]

When analyzing stories, the exploration of contradictions and silences—places where a text does not make sense or does not continue—proved to be a valuable endeavor (COPELAND, 2019; STANLEY & TEMPLE, 2008). For this purpose, I transcribed pauses and emotions and retained them throughout the entire analysis process, as they emphasize important passages, reinforce shifts of attention outwards or inwards and provide indications of the narrator's attitude (CZARNIAWSKA, 2004; KIM, 2016). In this regard, FUJI (2010, p.237) noted that the importance of narrative research in the context of violence lies not only in the stories, but also in the accompanying metadata, including deliberate omissions or silences, which can both conceal and reveal. Analyzing these silences was facilitated by comparing narratives from different perspectives, for example by contrasting the narratives of Marian and Aurelia in relation to their experiences under the communist regime. Turning to gaps or silences offers deep insights into the ambiguity of human experience (SANDBERG, TUTENGES & COPES, 2015) and the complex layers involved in meaning-making (LEHMANN, MURAKAMI & KLEMPE, 2019). [35]

The analytical dimension of responsibility, unique to my dissertation project, can be omitted in other studies, but demonstrates the framework's potential for expansion. Given its relevance to researchers exploring narratives of war, violence, or terrorism, I briefly include it here. Responsibility is closely intertwined with other analytical dimensions of SNA, particularly stories and structure. In my analysis, I concentrated not only on what the stories presented by criminal courts or interview participants conveyed about responsibility, but also on how responsibility was constructed and ascribed through storytelling (MANDELBAUM, 1993). This focused approach provided insights into responsibility as a narrative construct with "many faces" (AUHAGEN & BIERHOFF, 2001) and fluidly changing meanings (STRIBLEN, 2020). [36]

To elucidate the narrative construction and representation of responsibility, I assessed at what points the discussion or ascription of responsibility appears in the narrative, and in which form. These forms included descriptions of personal experiences of violence or the struggle for justice and truth; the inclusion of a prologue about human nature and freedom at the beginning of an interview; the exposition of a "little theory about society" during the interview; references to other countries and their ways of dealing with past collective violence and repression; the retelling of fragments from documentary films or books; or through the telling of jokes. From these examples follows that responsibility is conveyed both through the content of the storytelling and the linguistic and rhetorical devices employed by the narrator (MANDELBAUM, 1993; TELES FAZENDEIRO, 2019). [37]

The analysis of responsibility ascriptions included an examination of the specific types and objects of responsibility invoked (i.e., responsibility for (doing) what), and the nature and variety of subjects' responsibility is transferred to (i.e., locus of responsibility, who or what is responsible). Additionally, I explored the underlying notions and conceptualizations of guilt and responsibility, considering whether these concepts reflected individual or collective understandings, were viewed as private or public matters, and indicated agent-focused or relational accounts of responsibility (RAUSCHENBACH et al., 2015; SKJELSBÆK, 2015). Notably, narratively constructed responsible subjects often diverged from "the broadly Kantian and distinctly modern account of moral agency" (HOOVER, 2012, p.238), and sometimes took the form of things and ideas such as Communism or abstract entities such as God. In narratives by survivors and descendants, for instance, God frequently emerged as a central figure in stories of victimization. For example, God was depicted as a savior or a source of survival during periods of despair, such as imprisonment, or as a source of strength in adapting to life under a totalitarian regime and in coping with ongoing injustices in the present, sometimes acting as a judge. [38]

In examining approaches to responsibility, I explored how narrators engage with the issue of responsibility more broadly, which was found to be intricately linked to the narrative's structure (TELES FAZENDEIRO, 2019). The focus was not on the narrator's own responsibility, but on how responsibility was utilized within the narrative—what was "done" with it. I analyzed how responsibility was woven into a narrative, including its various stories, threads, and fragments, and how this connected to the narrator's perspective and the moment of telling. Six distinct approaches were identified, representing different ways narrators address responsibility. These were not ideal types but rather illustrate various narrative strategies for dealing with responsibility. Each approach was defined by the positioning of the subject and/or object of responsibility in relation to the context of past collective violence and repression, as well as the narrator's perspective. By reconstructing narratives about the past through the lens of responsibility ascriptions and approaches, I uncovered the manifold ways in which the invocation, discussion, and omission of responsibility shaped and sustained meanings surrounding (past) collective violence, the country's history, and the narrator's life (AVRAM, 2022). [39]

4. Proceeding Through the Five Stages

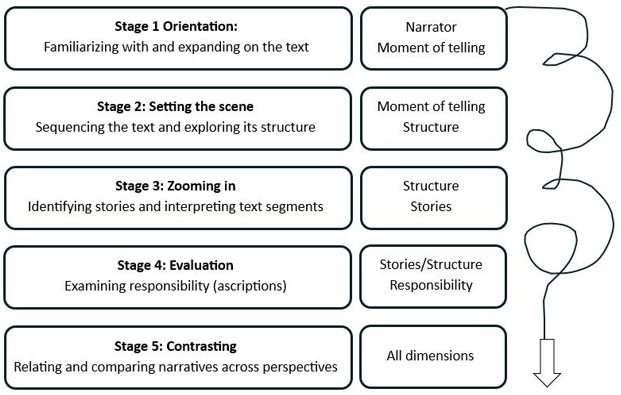

The second component of the SNA is a concrete five-stage analytical procedure to facilitate the systematic reconstruction and analysis of narratives derived from diverse data sources. In the procedure, the analytical framework is integrated into a sound research strategy by focusing each stage on at least two of the analytical dimensions, helping to organize the analysis process (Figure 2). The five-stage analytical procedure is designed to enable a structured yet flexible analysis, allowing "to consider each individual account within its own panorama" (PAMPHILION, 1999, p.393) and to relate them to each other and identify patterns and gain general insights. As such, SNA aligns with a holistic, interpretive approach to narrative analysis (JOSSELSON & HAMMACK, 2021; LIEBLICH et al., 1998; ROLÓN-DOW & BAILEY, 2022), focusing on the content, structure, and context of storytelling. It provides a systematic way to interpret individual parts through the overall text, while contextualizing understandings in relation to the narrator's positioning and the moment of telling [40]

In accordance with the analytical goals of my dissertation project, the first three stages—orientation, setting the scene, and zooming in—focus on the reconstruction of narratives about the past from court documents and interview transcripts. Following the principle of reconstruction, each text is interpreted without preconceived hypotheses, with the analytical dimensions guiding the analysis process. In the first two stages, the entire text is examined, while Stage 3 focuses on smaller text units, analyzing them in terms of content and structure. The fourth stage—evaluation—is centered on responsibility as a narrative construct in relation both to smaller text units and the entire text. Moving the analysis of responsibility to its own stage proved valuable in deepening my understanding of the variety and functions of responsibility ascriptions as a narrative-driven practice. Additionally, this separation enabled me to adapt SNA's analytical procedure for a concurrently conducted third-party funded research project. Depending on the research focus and the phenomena under investigation, this stage can be adjusted or omitted (Section 5). However, in projects dealing with complex narrative data, it is advisable to address the central research question in a dedicated stage, as this helps to organize the analytical process and offers clearer guidance. The fifth and final stage—contrasting— involves comparing narratives and responsibility ascriptions within and across actor groups, which supports theoretical generalizations based on individual cases and contrastive comparisons (ROSENTHAL, 2018, p.66).

Figure 2: Overview of the five-stage analytical procedure [41]

In practice, I conducted the analysis process through Stages 1 to 4 separately for each actor group, reconstructing each narrative "in silo" and analyzing how responsibility was ascribed and approached by each narrator without considering other perspectives (VOGL, SCHMIDT & ZARTLER, 2019). It was only in the final stage (contrasting) that the narratives were compared within and between actor groups to draw general conclusions. The analytical process was not linear; rather, it involved a constant alternation between individual interpretations and a more broader understanding of the text and the phenomenon under investigation—specifically, the ascription of responsibility (PAMPHILION, 1999). Although the division into five stages has proven useful for structuring the analytical process, it remains somewhat artificial, as it is difficult, if not impossible, to clearly separate, for example, the reconstruction of narratives from the analysis of responsibility as a narrative construct, since these elements are interdependent. The overlapping stages and the iterative process are represented in a spiral in Figure 2, illustrating the continuous back-and-forth movement during the analysis. [42]

The five-stage analytical procedure is designed to assist the reconstruction and comparison of narratives from different perspectives by focusing on the content and structure of the "told" as well as the "telling." In this way, the dialogical nature of storytelling and the significance of context in constraining and shaping the content and form of a narrative are taken into account. Methods of text and context interpretation (MISHLER, 1986; ZILBER et al., 2008) are linked, with the results of the analysis classified as relative to the positioning of the researcher during data collection and analysis (KIM, 2016). Accordingly, in SNA, thematic, structural, and dialogic-performative modes of narrative analysis (RIESSMAN, 2008) are integrated and different qualitative methods are linked in a "multimethod" approach (HENSE, 2023, §1). [43]

Reading texts in terms of content and structure and analyzing individual text segments, structures, or the storytelling context are not separate, sequential processes, but are interwoven and complementary throughout the five-stage analytical procedure (see for a similar argument e.g., BRIGHT & DU PREEZ, 2023). Researcher's reflexivity remains an essential element throughout the analytical process (JOSSELSON & HAMMACK, 2021; KIM, 2016). In this way, SNA incorporates a broad interpretative analytical toolkit that has proven useful for engaging with a multiplicity of perspectives and disparate types of data, such as court documents, interview transcripts, and field notes. This approach is in line with scholars who similarly opt to apply multiple methods "to elicit the most meaning from the data" (MERAZ, OSTEEN & McGEE, 2019, p.2). [44]

Fundamentally, the five-stage analytical procedure involved multiple readings of court documents and interview transcripts, considering my field notes, the drafting of different texts based on these original texts, and finally different interpretations, including translations. The multiple readings began during the fieldwork phase, when I transcribed the recorded interviews with the help of two research assistants according to a guide I had developed. Since transcription itself is already "deeply interpretive" (RIESSMAN, 2008, p.21), I opted for a verbatim transcription that captured the speaker's exact words, pauses, tone of voice and other non-verbal cues. I then conducted a new reading followed by several close readings throughout the analysis, adhering to the hermeneutic triad of explication, explanation, and exploration (CZARNIAWSKA, 2004, p.60). This recursive process, in which the whole sheds light on the parts and the parts, in turn, provide a richer and more intricate understanding of the whole, helped to identify and interpret text segments and units of meaning related to my research question. [45]

These multiple readings involved annotations of the text and memo writing. Memoing (KIM, 2016; OLLERENSHAW & CRESWELL, 2002) allowed me "to explore, contemplate, and question what is happening in the data" (ROLÓN-DOW & BAILEY, 2022, p.11). I used memoing to analyze and burrow into the narratives and stories of different actor groups (CLANDININ & CONNELLY, 2000) as well as to enhance my sensitivity to the data (ROLÓN-DOW & BAILEY, 2022) and to trace and reflect how my positioning to participants and/or their narratives and stories impacts my interpretation and findings (AVRAM, 2024b; JOSSELSON & HAMMACK, 2021). These notes and memos, along with entries from my field diary and literature review, were systematically incorporated into the "narrative log" I created for each narrative. This process helped focus the analysis, develop propositions from the data, and transition from data to conceptual assertions and generalizations. [46]

To thoroughly engage with the data, I analyzed the texts manually and created different versions by editing, rearranging, and adapting them (NASHEEDA, ABDULLAH, KRAUSS & AHMED, 2019; OLLERENSHAW & CRESWELL, 2002), as well as translating transcripts and court documents from Romanian into English. From the second stage onward, I used word-for-word translations of phrases or repetitive words, followed later by whole paragraphs. Functional translations were applied only when drafting the final research text. Writing was used as "a way of finding out, learning, knowing, discovering, and analyzing" (KARLSSON, 2008, p.45). It enabled me to explore both the content of what was told, how it was told and the reasons for these narrative choices, presenting the narratives coherently and recognizing the diversity of participants' experiences. [47]

As part of my doctoral research, I presented and elaborated on exemplary narrators and their narratives in greater detail for each actor group, supplemented with vignettes to introduce additional or contrasting perspectives from narrators within the same group (Section 4.5). In this way, the five-stage analytical procedure has similarities with the restorying approach, which involves transforming data into a coherent story that includes contextual information, interactions, events, characters, thoughts, and emotions (OLLERENSHAW & CRESWELL, 2002; ROLÓN-DOW & BAILEY, 2022). Through the process of writing, restructuring, and retelling individual narratives, I gained a deeper understanding of each participant's account (Stages 1-3), which facilitated the exploration of the ways in which responsibility is narratively constructed (Stage 4) and the extent to which narratives and responsibility ascriptions vary within and between groups (Stage 5). [48]

Guiding questions and the "process of posing and responding to questions" (SQUIRE et al., 2014a, p.98) were employed to navigate the various rounds of reading and writing. Like the biographical case reconstruction method (ROSENTHAL, 2018), which uses questions to develop hypotheses, I used questions to generate meaning from my data and reflect on my own positioning. The guiding questions varied depending on the group of actors and the level of analysis, but the overall aim was to develop a deeper understanding of the narrator in the moment of telling (see Section 4.1) and the narrative. Yet, I also posed overarching questions to every text—whether a court document or an interview transcript—such as: what is introduced and emphasized in the first part of a narrative; what comes up in the second part or through my inquiry? Which events and time periods are addressed and what is omitted? Where do these events take place and who is involved? How is the narrator positioned in relation to the events and/or actors involved? How is violence and repression addressed? Is responsibility a salient topic? What topics are addressed? In what detail are experiences or issues presented and why? Why is this topic, event, etc. introduced at this point, presented with this type of text? What linguistic devices does the narrator use at these points and why? These and other guiding questions, in sum, helped to disentangle and steer the analytical process (ROLÓN-DOW & BAILEY, 2022). [49]

Proceeding now through the five analytical stages, I outline the steps taken and techniques used to create meaning from court documents and transcribed interviews (see Table 1). Each stage begins with a general overview, followed by the analytical steps and strategies, illustrated with empirical examples from the dissertation project.

|

Stage 1: Orientation Familiarizing with and expanding on the text |

Narrator, moment of telling (context of storytelling) |

"Novel" reading (exploration) while listening to audio-recordings and memo-writing |

|

|

|

Contextualization through field notes and literature research oriented by guiding questions |

|

|

|

Second reading (explication) and writing of "narrative log" |

|

Stage 2: Setting the Scene Sequencing the text and exploring its structure |

Moment of telling, structure (structure of storytelling) |

Summarizing text and creating a "skeleton" document containing section and paragraph summaries |

|

|

|

Exploring the composition of the text and its temporal and linguistic structure through memo-writing |

|

|

|

Re-organizing the "skeleton" document according to temporal and thematic markers and supplementing the "narrative log" |

|

Stage 3: Zooming In Interpreting text segments and re-storying the text |

Stories, responsibility (content of storytelling) |

Distinguishing narrative threads and stories through analysis of events/episodes and actions, and their connection |

|

|

|

Analyzing characters, themes, including the portrayal of collective violence and repression, and silences/contradictions |

|

|

|

Restorying the results from this and previous stages in a written format |

|

Stage 4: Evaluation Examining responsibility (ascriptions) |

Responsibility (phenomenon of interest, adaptable) |

Analyzing responsibility ascriptions with connection to violence and repression |

|

|

|

Analyzing responsibility ascriptions beyond their connection to violence and repression |

|

|

|

Analyzing and categorizing approaches to responsibility |

|

Stage 5: Contrasting Relating and comparing narratives across perspectives |

All dimensions (cross-case analysis) |

Contrasting of narratives oriented by guiding questions and with the help of over-sized mind-maps (within actor groups) |

|

|

|

Writing and retelling a comprehensive text for each actor group including deviant perspectives |

|

|

|

Contrasting of narratives across groups and writing the final research text |

Table 1: Overview of the steps taken during the five-stage analytical procedure [50]

This first stage focused on familiarizing with the text—whether a court document or an interview transcript—and situating the courts and interviewees within their respective contexts. This involved two types of readings of the text, along with an expansion of the text by incorporating field notes and literature research. The analytical focus was on the narrator and the moment of telling, specifically addressing who is telling the story, in which context, and why. [51]

First, I applied a "novel reading" (CZARNIAWSKA, 2004, p.62) that allowed me to personally dwell on the stories without immediately analyzing them, as well as listening to the audio recordings (JOSSELSON & HAMMACK, 2021; NASHEEDA et al., 2019). As GEE (1991, p.17) noted, understanding how an utterance is spoken is decisive for the structure assigned to it. Due to the length and sensitive content of the texts, this process was time-consuming and involved frequent interruptions. During and after this initial reading, I wrote memos to document general observations, questions, and initial ideas about the structure and content of the narrative. These memos were compiled into the "narrative log" together with a reflexivity section on my thoughts and reactions toward the content, the narrator, and the listening process. [52]

Next, I considered "what else we know about the narrators and their local and general circumstances" (MISHLER, 1986, p.244) and expanded the text using my field notes and an extensive literature review, including biographical, historical and socio-political data (ROSENTHAL, 2018). The objective was to contextualize the trials and interview recordings within the moment of telling and to situate the courts and interviewees as narrators within their respective horizon. Managing the extensive information required careful selection. For instance, while classifying interviewees, literature and field notes were considered, and materials provided by the interviewees were excluded to ensure data parity and facilitate orientation. Additionally, guiding questions tailored to each actor group, assisted in expanding the text and selecting pertinent literature, as illustrated for judicial narratives (Box 1).10) These questions guided the reading and memo writing in Stages 1 and 2 and helped me to contextualize the courts and the text. Exploring the courts as narrators required a thorough examination of trial proceedings, historical and political contexts, and legal frameworks. Collaborating with a research assistant knowledgeable in Romanian criminal law, the analysis of the courts' perspectives and the interpretation of judgments took eight months. To streamline such analytical processes, consulting experts is recommended, especially when dealing with documents containing unfamiliar terminology.

|

What is the socio-political, historical and legal context of the initiation of the trial (indictment)? What kind of institutions were involved? What crimes were adjudicated, how were they qualified? What is the setting of the trial and how was its course? What kind of evidence is it based on? What kind of sentences were pronounced and served? Who was involved in the different trial stages and what was their positioning? What was the perception and presentation of the trial then and now? Is the judgment in a particular tradition? Is it readable (simplicity?) and what other (material) peculiarities are existent? Are there any peculiarities about the style? How is the judgment structured and what are its focus areas (in terms of length or font)? What is the relation between evidence (factual account) and reasoning (legal account)? What kind of accounts, threads and stories are included? |

Box 1: Excerpt of the guiding questions for judicial narratives in Stages 1 and 2 [53]

After expanding the text and considering the storytelling context, I conducted another reading to enhance comprehensibility, akin to explication (CZARNIAWSKA, 2004), by rendering the text in clearer language. Information was added in more accessible terms, leading to slightly altered transcripts or heavily modified court documents. For judgments, I outlined the structure and translated legal terms, while for interview transcripts, I focused on content-related questions concerning historical events, characters, or organizational units within the communist regime. Based on this reading, I recorded impressions and observations about the narrator, the moment of telling, and the structure in the "narrative log." This included notes on the narrator's biography and her/his self-presentation, including how they presented their agency (O'CONNOR, 2000; RAUSCHENBACH et al., 2015; SCHIFFRIN, 1996) as well as linguistic peculiarities such as repetitions or proverbs, and both implicit and explicit references to me (i.e., the audience). Additionally, a section with preliminary ideas on responsibility, its ascription, and significance for the narrator was included and continuously updated in subsequent stages. By the end of this stage, the "narrative log" comprised four to six pages, which helped me to set the focus of the analysis in the following stages. [54]

The second stage involved a deeper immersion in the text and its organization, focusing on the form and structure of the narrative. Attention shifted from the context to the structure of storytelling, though the analytical dimensions of the narrator and the moment of telling remained relevant. In addition to exploring the structure of the narrative, i.e., how is the narrator telling, the focus was also on consolidating ideas from the first stage, e.g., identifying and interpreting the story about the self and understanding the core of the story. Strategies such as summarizing, rewriting, and rearranging the text proved effective in navigating the text, recognizing its structure, and identifying key content, thus preparing for the in-depth analysis of individual text segments in the next stage. In total, I took three steps to divide the text into segments and examine the (linguistic) structure and forms of both judicial and personal narratives. [55]

First, I summarized parts of the entire court document or transcript in English, retaining the original text. The criteria for determining where a text section begins and ends included changes in speaker, text type, content, or topic, as well as entrance or exit talk (RIESSMAN, 2008; ROSENTHAL, 2018). In the summaries of the sections, I noted the most important points of the section, which episodes and events or actors were included, as well as when statements were made about the past, violence and repression, and responsibility. In Box 2, I illustrate this strategy using the example of Marian's transcript. In the excerpt, initial ideas (e.g., self-portrayal as Robin Hood) or questions (e.g., reference to me) are noted in brackets. Hence, Marian rarely addressed me directly during the interview, but his references to Germany could be due to my position as a researcher and doctoral student at a German university. Following this summarizing exercise, I created a "skeleton" document containing section and paragraph summaries, providing an overview of the text's structure and components, and on the salience of the issue of responsibility for the narrator in the moment of telling.

|

He does not answer my question about the number of informants, but talks about how and for what they have used the collected information, i.e., also to inform (whom) about the popular spirit (even though it wasn't their task). In a small insertion, he goes back to the belief that the Securitate was better off. [Interview transcript in Romanian, 8 lines] Retells a small episode (shortly after the revolution?) of how he acted in service (like a Robin Hood) and even defied the rules for the people, underlining that there was a huge difference of the Securitate in which he worked compared to before 68 (Pauker's times). [Interview transcript in Romanian, 20 lines] Then he comes back and gives references to other countries (Germany, indirect reference to me?) to make the point that Romania was no different/worse, the Russians are again the enemies. He also points to the Stasi system that was similar to Securitate practices in 1968 (which is opposite to O. and survivors) [Interview transcript in Romanian, 13 lines] |

Box 2: Example of summarizing parts and sections of Marian's transcript [56]

Using the "skeleton" as a kind of table of contents, in a second step, I explored the sequential order, i.e., the temporal and thematic organization, of the text by writing analytical memos. I paid particular attention to the beginning and end of the text, the frequency or length of the topics addressed, the repetition and form of the sections—e.g., argument, description, narrative, monologue, anecdote, joke, insertions (DE FINA & GEORGAKOPOULOU, 2015; ROSENTHAL, 2018; SANDBERG 2022)—as well as sections without connections and their order. For instance, in my "narrative log" of Marian, I noted that he began both interviews, which were a year apart, with almost the same wording: "We have to look into the past to go further in the present. And here we have to see that there were good and bad things." This introductory statement, I wrote, serves as an orientation for Marian's narrative about the past; it resembles a prologue. Engaging with the question of why the former Securitate officer began with this statement in both moments of telling, I examined the overall structure and focus of his storytelling. This analysis revealed that the passage foreshadowed his self-presentation as an objective analyst who knows the "truth" and anticipated his interpretation of the country's past that contextualizes the communist era. Marian related violations and abuses ("bad things") to the installation and first two decades of the Communist regime, but not to the 1970s and 1980s. Coinciding with his active time in the Securitate, the last two decades of the Communist regime were depicted as a secure era in which patriotism and professionalism ("good things") prevailed. [57]

In addition, I examined the temporal and linguistic structure of the text. To identify the referred or invoked time/temporality, for example, I marked episodes and events according to their temporal frame in different colors, including different pasts (e.g., distant and near), transitional phases, as well as the present and future, paying attention to their temporal or causal interconnectedness and sequence in the narrative. In this manner, I recognized that Marian's storytelling constantly alternated between the interwar period, the ANTONESCU regime, the installation of the Communist regime in the 1940s and 1950s, his own period of active employment with the Securitate, the democratic transition phase in the 1990s, and the present. With this polychronic mode of storytelling progressing towards the present, Marian's narrative about the past portrayed Romania as a chess piece in global power politics, its fate directed by obscure outside forces, invoking the idea of an alleged cyclicity or immutability of history. Consequently, the subjects of responsibility are positioned beyond the narrator's context and social life. [58]

Turning to the linguistic structure of the text, I explored repetitions of key phrases or refrains, as they emphasize the narrator's ideas and perspectives, provide evidence of their stance, and draw attention to their beliefs and point of view, revealing their understanding of the world and themselves and indicating the relationship of the self to society (PAMPHILION, 1999; TANNEN, 2007). For example, Marian used phrases such as "It's logical," "It's obvious," "Logical, isn't it?" extensively during both interviews. This "principle of logic" reflects the deterministic meaning he gives to the past and present, but also to his personal experiences as a former Securitate Officer. Furthermore, it posits that actions are governed by irrefutable logical laws, operating statically and according to rules, much like natural laws, thereby leaving little room for personal agency. [59]

I also investigated the use of reported speech, interpolations, and digressions (PRESSER & SANDBERG, 2015b; WORTHAM & RHODES, 2015). These elements signal important sections, help to construct role constellations, provide insights into the narrator's self-conception, and convey the story about the self. For example, Aurelia, who survived one of the notorious communist prisons at a young age (17-23), expressed a desire to share "something else she has been thinking about these days" at the end of our conversation. The 83-year-old interviewee then recounted an episode from her school days involving a note from a former French teacher that read: "Ad augusta per angusta." This Latin phrase, meaning "through difficulties to greatness," illustrates how Aurelia perceived and presented her life as a journey marked by obstacles, including imprisonment and the challenges she faced after her release, yet ultimately leading to a fulfilling conclusion. This self-presentation is also reflected in the structure of her storytelling. While her experiences in prison took on a relatively marginal role during the interview, Aurelia discussed the fate of people close to her or details about her education and later success as a translator at length. Her story of transformation is also reflected in the main message conveyed in the interview (i.e., the core of the story), namely "that you can overcome many hard situations, and that things do change" (for a more detailed consideration of Aurelia's message, see AVRAM, 2024b). [60]

In a final step, I organized the summarized and modified version of the text ("skeleton") according to temporal and thematic markers (KIM, 2016, p.203), as can be seen in the following example from Marian (Table 2). This document lists narrative threads or stories that are roughly categorized according to their subject or theme (e.g., story about the self, its institution, the past), as well as story elements (episodes, characters, themes), ascriptions and approaches to responsibility, and (linguistic) peculiarities. The individual sections contain subtitles that emphasize the descriptive and analytical focus of the narrative (NASHEEDA et al., 2019). This document formed the starting point for zooming in on the stories, their elements, and how these relate to one another (BEAL, 2013) in the next stages.

|

Story About the Self Family background and education Recruitment into Securitate and career path until now Self-presentation Episodes of personal agency |

Story About the Securitate |

Story About the Past (History) General remarks Presentation of communism, former regime CEAUȘESCU A Better Past |

|

Story About the December Events of 1989 |

Story About the Transition/Present Reasons for the shift Continuities (but also differences) A fatal dead end |

Episodes/Actions |

|

Actors/Characters Romanian population Russians Intelligence services Individuals |

Themes Linking past and present Patriotism Violence and human rights violations About truth Silences |

Criminal Justice/Trials VIȘINESCU URSU case

|

|

Responsibility Collective responsibility, defect Transcended responsibility for past violence Responsibility regarding Revolution, CEAUȘESCU's execution Other individuals Responsibility for the present |

Peculiarities (Language) References to other countries (Germany) as a legitimizing strategy to his account, sense-making References to books (underlining his self-presentation as an objective analyst) Polychronic storytelling Principal of logic metaphors |

|

Table 2: Headings of Marian's modified and re-organized transcript [61]

In this stage, the analytical focus shifted from the structure to the content of storytelling, and more specifically to the analytical dimension of stories and responsibility. Based on the previously rearranged and modified text, narrative threads, fragments, and stories were further differentiated and interpreted, and individual text segments were analyzed in more detail. The focus was on the question of which (kind of) stories the narrator presents and interweaves during the telling and why, and which ascriptions of responsibility are present in these stories. [62]