Volume 25, No. 2, Art. 4 – May 2024

A Recipe for Successful Collaboration: Shared Creative Work Experiences (SCrWE) Among Co-Researchers

Crystal D. Howell & Libba Willcox

Abstract: In this article, we discuss our home cooking school as one example of a strategy we call "Shared Creative Work Experience" (SCrWE, pronounced "screwy"): Planned, playful extra-research activity during which collaborators engage in and reflect on creative work (e.g., cooking, sewing, painting, building, writing, performing, designing, gardening) that yields a product of some sort (e.g., a meal, a quilt, a painting, a shelf, a poem, a play, a game, a communal garden). Through SCrWE, we argue, collaborators playfully but deliberately create disequilibrium, shift perspectives, and unsettle power dynamics, ultimately preparing for productive, meaningful research partnerships. By creating a space for co-researchers to experience shared creative work, we aim to disrupt taken-for-granted assumptions and invite co-researchers to embrace ambiguity together. Grounded conceptually in aesthetic experiential play and the notion of the social imagination, SCrWE helps research teams identify potential sources of substantive, procedural, and affective conflict and then explore these conflicts in productive ways. Using techniques of collaborative autoethnography, we weave together recipes, photos, and scholarly writing to illuminate our experiences. We conclude by describing the steps for developing a SCrWE and include reflective questions to help research team members uncover their ontological, epistemological, and axiological commitments, ultimately leading to more meaningful research partnerships.

Key words: research collaboration; imagination; aesthetic experiential play; collaborative autoethnography; creativity; extra-research strategy; embodied knowledge; somatic knowledge

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1 Common collaborative challenges

2.2 Strategies for successful collaboration

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1 Aesthetic experiential play

3.2 Sociology of imagination

4. Mode of Inquiry

5. SCrWE Outcomes

5.1 Unearthing unconscious beliefs

5.2 Developing intersubjective understandings

5.3 Engaging ethically and aesthetically

6. A Recipe for SCrWE

"Cooking school" was born in the last years of our doctoral programs at a large U.S. university. When our coursework ended and we began to work in earnest on our dissertations and, eventually, job searches, we found ourselves isolated and stressed. We needed nourishment: The friendship sort as well as the actual food sort. Graduate school too often means a coffee-and-junk-food subsistence for reasons of convenience and finances, but we wanted real food. Like humans across the world for the last 14,000 years (D'COSTA, 2018), we wanted bread. We wanted pasta. We wanted salads and stews and delicate, almost creamy salmon en papillote with the briefest drizzle of olive oil and black pepper. [1]

Ever good curriculum scholars, we decided a cooking school would help meet our needs. Crystal is a skilled home cook. Libba wanted to learn more. We considered the organized bodies of knowledge we wanted to dig into and the experiences that could lead us there (EISNER, 1994); specifically, we discussed the broad categories of foods we wanted to cook and some of the skills we wanted to master. We met weekly in Crystal's kitchen. Each week, we decided on a menu and negotiated the work of shopping, prepping ingredients, cooking a meal, and cleaning up the kitchen together. And each week we enjoyed a meal together. We put our loneliness and dissertations away and engaged in playful explorations of life outside of academia. [2]

Cooking school was labor, certainly, and in practical terms fed us for the evening (and often the next day, in the form of leftovers), but we shared that labor. Cooking school was also creative, playful, and pleasurable. As the year continued, we began to connect our cooking school experiences with our experiences as researchers, often comparing and contrasting collaboration in these two domains. Ultimately, we found that cooking school enriched our academic work and specifically prepared us well to conduct research together. Cooking school is just one example of a strategy we call "Shared Creative Work Experience" (SCrWE, pronounced "screwy"): Planned, playful extra-research activity during which collaborators (in-person or virtually) engage in and reflect on creative work (e.g., cooking, sewing, painting, building, writing, performing, designing, gardening) that yields a product of some sort (e.g., a meal, a quilt, a painting, a shelf, a poem or piece of prose, a play, an analog or virtual game, a communal garden). Although we recognize that it is impossible to fully capture an aesthetic experience for someone else, in this article we have intentionally included recipes and photographs of cooking school to provide readers with a glimpse of the ineffable elements of our experience. As we will describe in greater detail in our conceptual framework, the intersection of aesthetic experience, play, and imagination yields messy but meaningful outcomes. Providing only guidance for creating one's own SCrWE would make the process seem too straightforward, we feared; we include these glimpses of cooking school not to prescribe a single way forward but to share one iteration of what we imagine SCrWE might be. Through SCrWE, we argue, collaborators playfully but deliberately create disequilibrium, invite vulnerability, shift perspectives, and unsettle power dynamics, ultimately preparing for productive, meaningful research partnerships. [3]

Although we discuss aspects of play as it relates to aesthetic experience in the conceptual framework section of this article, it is essential for readers to begin with some understanding of how we understand play and regard its role in our experiences during cooking school and other SCrWEs. We regard play as an essential element of human life, not a luxury. Evolutionary psychologist GRAY (2009) defined play as "activity that is (1) self-chosen and self-directed; (2) intrinsically motivated; (3) structured by mental rules; (4) imaginative; and (5) produced in an active, alert, but nonstressed frame of mind" (p.480). GRAY hypothesized that for hunter-gatherer societies, social play is "an exercise in governance" requiring "voluntary participation, autonomy, equality, sharing, and consensual decision making" (p.485). Children across cultures and times engage in play, pretending to be "powerful, competent adults, doing beautifully and skillfully what they see the adults around them doing" (p.511). Although their "conscious motivation is fun, not education" (ibid.), children learn to cooperate with others through play, preparing them for adult life. BROWN and VAUGHAN (2009) articulated seven similar properties of play, three of which we see as particularly relevant: Play's "inherent attraction," "diminished consciousness of self" among players, and "improvisational potential" during play (pp.17-18). Play ought to be appealing, in other words, and engrossing enough that players lose some inhibitions while playing. [4]

SUTTON-SMITH (2001) described seven rhetorics of play rather than defining it. Like SUTTON-SMITH, we find these discourses of play helpful to consider as sites for critique. Pertinent to our work are the rhetorics of play as progress and play as frivolous. As SUTTON-SMITH explained, play as progress refers to the assumption that animals and children (but, importantly, not adults) "adapt and develop through their play" (p.9). Play as frivolity is related, referring to the idea that play is naught but "idle" or "foolish" (p.11). He later expanded on the rhetoric of play as frivolity, asserting that "each rhetoric involves an internal polarity between good play and bad play and uses the term frivolous for whatever kind is chosen as bad play" (p.204). GRAY (2009) and SUTTON-SMITH (2001) both clearly pushed back on these rhetorics, instead arguing that play is vital for the development and maintenance of community across the lifespan. We agree: Many of the activities we describe as part of cooking school may seem superficial or frivolous—like "bad play"—at first glance because baking bread can simply be fun (Table 1 and Figure 1). But we argue that these seemingly unserious moments provide a space to nurture the discovery and articulation of latent beliefs, creativity, and theoretical and practical negotiation skills necessary for successful collaboration within research teams. We recognize that other scholars have used play as a metaphor to describe disruption (RICHARDSON, 1997) or different ways of approaching work (RUSSELL, 2006) within the academy. We, however, embrace play not as a metaphor but as an important and enacted component of research teams' work.

|

Ingredients 2.25 teaspoons instant yeast (SAF Red Instant brand recommended) 1 cup plus 2 tablespoons warm water (about 105°F/40°C; if it feels hot to make you say "Ouch!" or pull back your hand, that's too hot for your yeast friends) A pinch of brown sugar or spoonful of honey (optional) 4 heaping cups plain flour plus more for dusting 1.5 tablespoons kosher salt (Diamond Crystal brand recommended) A few tablespoons of olive oil (other neutral or lightly flavored oils are also fine; this ingredient is optional) Work time: 30 minutes Total time: 3 hours plus several hours for cooling Bread requires three ingredients: Flour, water, and yeast. For bread that is good as well as nourishing, a generous pinch of salt is also required. A little sugar can be helpful but isn't essential. To make a basic loaf of bread, you will need a large bowl, a small bowl, plain flour, a measuring cup and spoons, and flaky kosher salt. Turn on the hot water tap, and while you wait for it to warm up, measure two and a quarter teaspoons of instant yeast into your small bowl. If the yeast has been living in your freezer for a while, add a pinch of brown sugar or a spoonful of honey, laying out a sugary feast for the yeast as it activates and awakens. Add a couple of tablespoons of water when it's warm but not too hot and stir. In short order, the yeast should come alive, frothy and fragrant. Scoop four heaping cups of plain flour into your big bowl and a tablespoon and a half of salt. Give it a quick stir and then add your yeast mixture, which should now be topped by a pungent, foamy head. Then add a cup of warm water while stirring, stirring, stirring. It doesn't seem like enough water at first, but be patient. If it's humid—and it often is here in Virginia—you may need to add another spoonful or two of flour. The mixture will come together suddenly as a shaggy mass in your bowl. (When we first made bread, we didn't understand what recipe authors meant when they described dough as shaggy, but now we do: The dough should be rough, with bits and strands sticking out from its surface. It is bedraggled, like a sheepdog after a rainy day.) If your bowl is wide and shallow enough, start to knead it right in the bowl; if not, turn it out onto a lightly floured surface. Then use the heel of your hand to press the dough down and away. Rotate the bowl as you knead, giving it half turns as you continue to press down and away, down and away. After a few minutes, your shoulder will be tired, but your dough will be a lovely, smooth ball. Return the dough to the bowl if you removed it, and drizzle some oil on top. Give the dough a few turns around the bowl, making sure the dough and the interior surface of the bowl are coated lightly with the oil. (You don't have to do this step, but it makes it easier to get the dough out of the bowl later.) Cover it with an airtight lid or some plastic wrap and set it in the warmest spot you can find; sometimes this means stopping a load of laundry in the dryer and nestling it amongst the hot towels and socks. While you wait for the dough to do its work, tidy up any floury mess. Call a friend. Sit on the porch. Have a drink and read a book or grade some papers. After an hour and a half or so, get out a big Dutch oven. Appreciate the enameled cast iron, the interior ivory and the outside colorful. Heave the whole thing, lid and all, in the oven, and turn the temperature to 415°F/210°C. Listen to the gas flame whoosh to life, and wait for the Dutch oven to slowly heat up and the bread to slowly rise. About a half hour later, the oven should be radiant with warmth and the bread twice its original size. Take out a thin, smooth tea towel and spread it on the counter. Dust it with flour and then flop the springy dough on it. Gather two corners of the towel in each hand and twist them together, like the wrapper on a peppermint. Roll the dough around in the flour, using the motion to form the dough into an even oval loaf. This is fast, easy bread, so don't worry about a second rise. Instead, retrieve the fully heated Dutch oven from the big oven and sit in on the stovetop. Take off the lid and, using the tea towel, gently slide the loaf into the Dutch oven. With your sharpest knife, cut a quick design on top: Maybe just some slashes, maybe a leaf, maybe a swirl. Put the lid back on and quickly slide the Dutch oven back into the big oven. Set a timer for 30 minutes. When it dings, remove the lid from the Dutch oven. The loaf should be steaming and blonde, its rough surface already enticing. Set the timer for 15 more minutes. When it dings, remove the Dutch oven from the big oven. The bread should now be deep brown. Carefully—carefully!—tip over the Dutch oven to let the bread flop onto the counter. Pick it up and tap the bottom, listening for the satisfyingly hollow thump. Quickly move the bread to a cooling rack. Your kitchen will now smell like heaven—the aroma alone the first time Crystal baked a loaf of bread explained to her why so many early Christian writers use bread as a metaphor for life. Try to let the bread fully cool. If you do, the texture will be better, but we can seldom manage that many hours of patience, so instead, feel free to cut yourself a slice while it's still warm (see Figure 1). |

Table 1: Crystal's basic bread recipe

Figure 1: Loaf of bread [5]

We begin with a short review of the literature (Section 2) related to common collaborative challenges and strategies for successful collaboration. We continue by describing our conceptual framework (Section 3), interweaving HOFSESS's (2013, 2015) aesthetic experiential play with FUIST's (2021) sociology of imagination. We then describe our mode of inquiry (Section 4) followed by the outcomes of our ScrWE, cooking school (Section 5). We conclude the article by suggesting a "recipe"—that is, guidelines for readers to plan their own SCrWE (Section 6). [6]

Our first few cooking school sessions focused on foundational recipes and skills we could then use when making other dishes. Poaching chicken breasts came early in the curriculum as we imagined the many soups, salads, and sandwiches in which we might use them. Libba prides herself on being flexible and open to new things, but the week we planned to poach and use chicken to make a summery chicken salad, that flexibility was tested.

Libba: I hate mayonnaise. I don't just kind of dislike it: I hate it. Even writing the word now triggers a swell of nausea and makes me recoil a little from my keyboard. Before our chicken salad evening, I was nervous. Would I be able to contribute to this collaboration? Would my vetoing specific ingredients for no reason other than not liking them seem like a lack of desire, motivation, or willingness to engage? Would I vomit in Crystal's kitchen? [7]

Libba's mayo fears seemed like a distillation of her many self-doubts, in the kitchen and as a scholar. So she began our session with avoidance. At first, Libba hedged with questions like, "Can we make the chicken salad with healthy ingredients?" and "Can we make this cleaner, with fewer preservatives?" but Crystal's suggestions of healthier, homemade mayo were still mayo. The situation required vulnerability: Libba knew she needed to come clean. Actual negotiations could only take place if Libba were transparent about her needs and desires. This situation, full of low-stakes conflict, taught us to share and discuss individual challenges pertinent to our shared goals and brainstorm solutions; it also taught us to use Greek yogurt to make chicken salad (Table 2 and Figure 2). [8]

As researchers, we recognized that experiences like this—moments of friction followed by negotiation—had been part of the academic work we had done with others. Sometimes these frustrating experiences still led to positive outcomes; sometimes they did not. We also knew that we were not alone in this regard (see, for instance, McGINN, ACKER, VANDER KLOET & WAGNER's [2019] description of the complex, often illogical use of researchers' time and resources in grant-funded projects with large research teams). Many research teams experience unproductive conflict or avoid conflict and leave challenges unresolved, resulting in uneven distributions of labor, disagreements about project ethics and goals, and hurt feelings, at times so severe that research projects are abandoned (McGINN, SHIELDS, MANLEY-CASIMIR, GRUNDY & FENTON, 2005). Conflicts are bound to arise: Like CORNISH, ZITTOUN and GILLESPIE (2007), we believe conflict, in fact, should arise and be used purposefully by research teams. However, conflict must be acknowledged, managed, and reflected on together in order for it to be productive. Like GUBA and LINCOLN (2005), we understand that explorations of paradigms (including ontological, epistemological, axiological, and methodological questions) are essential among research team members. Many research teams who express nominal paradigmatic agreement do not examine that agreement (BLUMER, GREEN, MURPHY & PALMANTEER, 2007). Collaborators may work under the same named paradigm, but fail to fully understand the nuance of their beliefs and practical commitments. It is necessary to critically examine the foundational axioms guiding research teams, before research begins, to maximize productivity, efficiency, and pleasure.

|

Ingredients 1½-2 pounds boneless, skinless chicken breasts (3-4 large breasts) 8 cups cold water (enough to generously cover the chicken breasts) A very generous pinch plus 1 teaspoon kosher salt 1 cup Greek yogurt1) 1 teaspoon lemon juice 2-3 tablespoons buttermilk 2-3 tablespoons white vinegar 2 teaspoons Worcestershire sauce 1 clove garlic, minced ½ teaspoon black pepper Zest of half a lemon 2 ribs celery, minced 1 cup pecans, roughly chopped2) 3 shoots green onion, diced ½ cup fresh basil, cut chiffonade 2 tablespoons local honey Work time: 20 minutes Total time: 1 hour Trim your chicken breasts of any excess fat or gristle. Place chicken in a single layer in a sauce pot and cover with cold water. Add a very generous pinch of kosher salt. Cook over medium heat until water starts to boil gently. As soon as the water starts to boil, flip the chicken breasts over, turn off the heat, and cover with a tightly fitting lid. Allow the chicken breasts to rest and continue cooking in the hot water for 5-10 minutes or until the breasts register 150F°/65°C on an instant-read thermometer. As Zoe DENENBERG and the editors of Bon Appétit (2024) reminded readers, the exact amount of time depends on the size of your chicken breasts, so "always check sooner rather than later if you're not sure—you can always cook them longer, but you can't uncook them" (§7). Once your chicken has come to temperature, remove it from the water and let it rest on a plate. If you're prepping the breasts ahead of time, cover and refrigerate them. If you're ready to use them now, let them rest for at least 5-10 minutes so you don't lose any juiciness. While the chicken rests, whisk together Greek yogurt, lemon juice, white vinegar, Worcestershire sauce, buttermilk, and black pepper until smooth and creamy. Mince garlic, and cover with remaining salt. Use the back of a fork to mash the salt into the garlic, rocking the fork back and forth until it creates a paste. Whisk garlic paste into yogurt dressing. Taste the dressing, and don't be afraid to adjust the seasoning to your liking: Add a little more salt, some freshly cracked pepper, or other herbs. (We like parsley and dill.) When chicken breasts are cool enough to handle, shred using two forks. Alternatively, chop your chicken into uniform chunks the size you desire; bigger works better for eating like a salad, smaller if you're planning to make sandwiches. Stir chicken, lemon zest, celery, pecans, and basil into the Greek yogurt mixture. Taste, and add salt, pepper, and lemon zest as desired. Drizzle honey on top. Enjoy over butter, Bibb, or Boston lettuce or as a sandwich; this salad is also great in the summer when tossed with a hearty, whole-wheat pasta or barley and served chilled (see Figure 2). |

Table 2: Libba's favorite no-mayo chicken salad recipe

Figure 2: Chicken salad [9]

2.1 Common collaborative challenges

BURNETT and EWALD (1994) described three domains in which collaborative challenges occur: The substantive, the procedural, and the affective. The substantive domain includes "content, context, and concepts" (p.22), the foundational elements of the research endeavor. Challenges in the substantive domain are not unwelcome, particularly at the beginning of a partnership. Collaborators, however, must address these challenges. "Stalemates among collaborators about ways to formulate research questions, choose methodologies, or shape articles generally stem from theoretical positions; exploring the issues that define these differences is productive and, we believe, necessary" (ibid.). [10]

The procedural domain "deals with how things should be done" (ibid.). Often this domain concerns management and logistical concerns for the research. The procedural domain covers time, project, and resource management. It speaks to clarity about leadership roles (including authorship responsibilities), and communication format, expectations and norms. Other components of this domain include understanding of institutional processes like Institutional Review Board submissions, grant applications, university requirements and institutional goals, as an essential part of successful collaborations (GAZIULUSOY, RYAN, McGRAIL, CHANDLER & TWOMEY, 2016). [11]

The affective domain "deals with interpersonal and emotional reactions" among research team members (BURNETT & EWALD, 1994, p.22). CHERUVELIL et al. (2014) likewise regarded interpersonal skills as important components of research collaborations and break these skills into two subcategories: Social sensitivity ("the capacity to navigate a full range of social relationships or interactions") and emotional engagement ("the presence and depth of feelings, both personal and professional, toward other team members and the project as a whole") (p.32). These feelings are important: BENNETT and KIDWELL (2001) noted that "the affective bonding perspective"—that is, an individual's connection to other group members and the group overall—"suggests that individuals provide or withhold effort based on their emotional attachments" (p.731). [12]

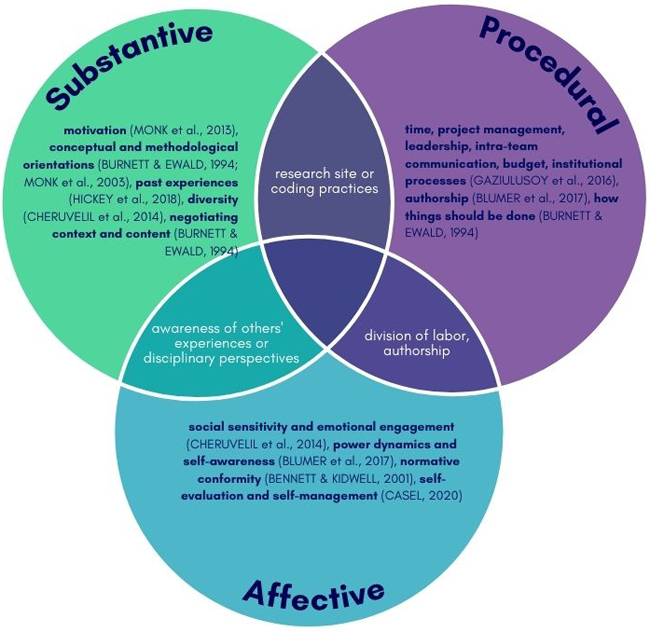

Finally, BURNETT and EWALD (1994) argued that "various kinds of conflict may spill over into each other" (p.22). In Figure 3, we identify potential sources of conflict as indicated by the existing research and our personal experiences, including conflicts that might arise in the overlapping areas. In the procedural/substantive overlap might be disagreements about the research site or coding practices. In the substantive/affective overlap might be stumbling blocks related to a team member's lack of self-awareness regarding their responses to or understanding of other members' past experiences or specific disciplinary perspectives. In the procedural/affective overlap might be frustration related to the division of labor (including emotional labor) and how that labor is represented by authorship. Moreover, these intertwined challenges point toward the need for more significant conversations among research team members: About their individual and shared relationships to knowledge, about understandings of their own and participants' subjectivities, and about the practical incorporation of research processes given these relationships and understandings (CORNEJO, BESOAIN & MENDOZA, 2011).

Figure 3: Common collaborative challenges [13]

2.2 Strategies for successful collaboration

People around the world have made pasta and other noodles for millennia. FRANCHETTI (2018 [2017]) noted that the ancient Greeks first mentioned laganon (a flat, irregularly shaped pasta) between 1,000 and 800 Before the Common Era. LU et al. (2005) found even earlier archeological evidence of millet-flour noodles at a 4,000-year-old archaeological site in northwestern China. In an interview with Singaporean newspaper Today, Anna Maria PELLEGRINO, a food historian and a member of the Italian Academy of Cuisine, described the parallel but distinct development of pasta (typically distinguished by its reliance on durum flour) and noodles (made from regular wheat flour or rice flour), noting that "the way they are cooked, the pots, the types of cereals used, the preparation, ingredients and toppings are completely different and specific to each civilization," but highlighting "the need for nourishment and, above all, to share around the same table feelings and everyday life events."3) Similarly, researchers working in teams have independently developed and documented collaborative strategies. While these strategies address their particular research contexts, available resources, and specific points of contention, all lead toward the same overarching need for functional and equitable partnerships. In this section, we describe some of these strategies, focusing on research teams' theoretical or conceptual tasks (such as defining collaboration and clarifying values and assumptions) as well as pragmatic tasks (such as negotiating responsibilities and establishing clear communication channels). [14]

Successful research teams begin with a shared understanding of collaboration and its limits. As MATTESSICH, MURRAY-CLOSE and MONSEY (2001) described, research teams (particularly those with members from multiple organizations or disciplines) may come together with varying levels of shared mission and autonomy. McGINN et al. (2005) recommended soliciting how each team member defines collaboration and working by consensus to define the terms of their current collaboration. In doing so, research teams begin to create two important things: 1. a sense of inclusion and belonging and 2. mutual expectations for clear communication. Particularly for diverse research teams, developing this sense of belonging is essential. CHERUVELIL et al. (2014) sussed out several ways research teams may be diverse, such as ethnicity, gender, culture, career stage, past collaborations with other team members, mode (e.g., specialist, generalist), disciplines (and number of individuals in each), and points of view. Acknowledging that diversity can enrich but also complicate experience, HICKEY, RICHARDS, and SHEEHY (2018) stressed the importance of ensuring voices from all relevant groups are "respected and valued" and included "around the table" (p.30). CHERUVELIL et al. (2014) recommended "informal team outings" and "formal teamwork exercises, especially when they occur outside the workplace (e.g., [sic] in the field or in 'inspiring' venues)" (p.34) to foster belonging, noting that "these exercises can be a useful starting point for developing the policies for data collection, metadata creation, quality assurance/quality control protocols, data sharing, and co-authorship essential for proper team functioning and high productivity" (p.34). (We add here the suggestion of online activities for geographically distant research teams.) In a similar vein, LINABARY, CORPLE and COOKY (2020) discussed how planned individual and collaborative reflexive activity such as formal individual or shared journals and informal conversations can support research collaborations. They advocated for collaborative feminist reflexivity as a methodological approach and practice for collaborative research teams to coproduce situated knowledge, negotiate power dynamics, and foster caring relationships. [15]

Research teams must partner nurturing belongingness and inclusion with other pragmatic, "nuts and bolts" tasks. GAZIULUSOY et al. (2016), for example, asserted the need for effective communication about project aims, roles, and disciplinary assumptions. They emphasized how communication establishes trust and helps teams navigate inherent, institutional, and teamwork challenges. Establishing trust among team members requires transparency and agreement about responsibilities and concerns. In their survey of 241 successful journal article coauthors, BENNETT and KIDWELL (2001) found that "about half of the respondents reported that they had negotiated an informal contract deciding authorship order before the project began" (p.739). Clarifying disciplinary assumptions and values is also vital, especially for transdisciplinary teams. CHERUVELIL et al. (2014) called this kind of work brokering, highlighting with their choice of term the practical or business-like nature of the work as well as its high value. When tension remains even after team members clarify and negotiate significant assumptions and boundaries, CHERUVELIL et al. recommended explicit instruction on interpersonal skills. [16]

It is clear from this review of the literature that many scholars recognize how essential clear communication and belonging are for developing successful research teams. But previous strategies or approaches are missing a truly transformative component and an element of play. We argue that aesthetic experiential play provides this missing component. In short, unscripted and spontaneous events will occur in research, and these unexpected events cannot be solved alone with planned strategies. Research teams need aesthetic, playful encounters that require them to think and experience together in the moment, pushing them toward collective reflection and improvisation. [17]

SCrWE is situated in our ontological, epistemological, and axiological commitments to collaboration, creativity, imagination, play, and aesthetic experience. Conceptually, with SCrWE we rely on HOFSESS's (2013, 2015) aesthetic experiential play and FUIST's (2021) sociological understanding of imagination. In this section, we define and describe aesthetic experiential play in order to situate SCrWE within curious, aesthetic, and playful ways of engaging collaboratively and to contrast aesthetic experiential play's (and SCrWE's) intentionality with DEWEY's (2005 [1934]) understanding of aesthetic experience. We then use FUIST's (2021) sociology of imagination and GREENE's (1995a) social imagination to suggest how SCrWE enables co-researchers to unearth unconscious, subconscious, subjective, and intersubjective beliefs about knowledge, reality, and ethics—essential aspects of successful collaborative research. [18]

3.1 Aesthetic experiential play

We designed SCrWe to transform the relationships among co-researchers, allowing them to better understand their ontological, epistemological, and axiological commitments. By creating a space for co-researchers to experience shared creative work, we aim to disrupt taken-for-granted assumptions and invite co-researchers to embrace ambiguity and uncertainty together. Our aims mirror those of HOFSESS (2013, 2015) writing about aesthetic experiential play. According to HOFSESS (2013), aesthetic experiential play is

"a playful, curious, questioning, artful engagement with the world; an engagement that sparks an aesthetic swell, which moves us in surprising, unanticipated ways from play to its afterglow. In this sense, afterglow may be the unfolding answer to an open question, and the open question may be a place to play" (p.1). [19]

Aesthetic experiential play is the generative intersection between aesthetic experience and play. This intersection is fluid and fertile; it reverberates with possibility and opportunity. Embracing aesthetic experiential play, then, requires an ontological commitment and intention to linger in the unknown, embrace disruptive experiences, and imagine what could be. HOFSESS (2013) built on DEWEY's (1997 [1938], 2005 [1934], 2015 [1916]), GADAMER's (1986, 2004 [1975]), and GREENE's (1978, 1988, 1995a, 2001) theories of play and artistic-aesthetic experience. [20]

HOFSESS's (2013, 2015) ambiguity in conceptualizing aesthetic experiential play echoes the ambiguity she encouraged participants to embrace as a means of education and transformation. Aesthetic experiential play lives in an individualized liminal space; while HOFSESS found commonalities in her interactions with participants, it was the unique playfulness each person brought to the experiences she designed that yielded uncertainty or unpredictability—creating the very challenges that catalyze transformation and wide-awakeness (GREENE, 1978). [21]

According to HOFSESS (2013, 2015), aesthetic experiential play invites two related but distinct aesthetic elements: Aesthetic swell and afterglow. As with other aspects of aesthetic experiential play, HOFSESS carefully avoided defining these terms and instead described their effects while preserving their ineffability. HOFSESS (2015) "theorize[d] the swell as a movement that unmoors, and sets one adrift toward unanticipated, surprising possibilities" (p.4). The aesthetic swell occurs during play and disrupts taken-for-granted assumptions, generating opportunities to see things—especially familiar things—differently. The afterglow is the active, continuing moment when this seeing differently occurs. Like a postcoital interlude, the afterglow conjures reflection, play, and, at times, tension. [22]

SCrWE is a form of collaborative aesthetic experiential play intended to elicit an aesthetic swell and afterglow. Ideally, SCrWE—whether researchers cook, garden, quilt, or do something else—embodies DEWEY's (2005 [1934]) description of an experience. SCrWe is unified but not uniform; during SCrWE, intellectual, emotional, and practical elements emulsify. DEWEY's conception of aesthetic experience included varying degrees of intentionality, but in SCrWE—a planned and recurring series of events in which participants commit to play and possibility—aesthetic experiences are always overtly intentional. In order to better understand how aesthetic experiential play invites individual and collective understanding, we borrow from FUIST's (2021) description of the sociology of imagination. [23]

Imagination enables groups of people to collectively envision responses to specific problems. This collective vision is the essential foundation for all collaborative research. FUIST described imagination as a mental process that enables people to see beyond the real, past and present. According to FUIST,

"(1) imagination is a creative, higher-order mental process that draws on a variety of material for its enactment; (2) imagination is powerful; (3) imagination facilitates intersubjectivity; (4) imagination is socially constructive, and (5) imagination concerns itself with what may not exist, has not been experienced, transcends what is knowable, or is yet-to-be" (p.360). [24]

While philosophers and psychologists typically view imagination as an individual process, FUIST argued that sociologists think about it as both individual and collective. Imagination, FUIST insisted, is "essential for intersubjectivity" (p.364). Citing LIAO and GENDLER (2020), FUIST asserted that "how people communicate and act together relies on their ability to share images of the world and predict or creatively 'mindread' ... the behavior of others" (2020, p.364). Like FUIST, we see imagination as both a solitary and collective endeavor, and we offer SCrWE as a means to nurture it in both capacities, but particularly in its collective form. FUIST and other sociologists often discussed "social imaginaries" (p.363) as a macro phenomenon: For example, FUIST mentioned ANDERSON's (2006 [1983]) argument that mass media help to create a national imagined community. Via SCrWE, however, co-researchers can focus on how they fit together with one another in particular. For instance, when making salmon with lemony peas and rice (Table 3 and Figure 4), we developed a shared, nuanced understanding of "done" for the salmon. To be sure, this understanding relied in part on technical knowledge (e.g., that salmon would continue to cook even after we removed it from the oven, making overcooking a common error) but also on our ability to carefully and expressively describe the desired color and texture of the fish at various points during cooking. In other words, we had to come to share a complex aesthetic understanding—and had to be able to communicate that intangible understanding with one another, often transmediating sensory experiences (sight, smell, feel, and taste) with language and gesture.

|

This recipe by Gabrielle HAMILTON (2012) is all about the unexpected: How do such simple techniques and so few ingredients yield such a sophisticated dish? We chose to make this dish (like many others we made early in the cooking school curriculum) because we wanted to develop a technique that we might use in many other applications. HAMILTON relied on cooking the salmon en papillote [in paper]. This technique gently steams ingredients in wine, stock, or moisture from the ingredients themselves. In French cuisine, cooks often prepare delicate fish filets flavored with vegetables and herbs this way, but cooks in other regions of the world use similar techniques. In Mexican tamales, for example, corn husks envelope masa dough filled with cheese, vegetables, or meat as its steams, and in Indonesia's otak-otak, banana leaves encase a spiced ground fish filling. Like many of the other dishes we chose, this recipe requires ingredients we both often have on hand: Eggs, stock, frozen peas, lemons, and rice. (Leftover takeout rice, by the way, works great.) When making this dish for the first time, prepare to exercise your senses. As HAMILTON noted, the gently cooked salmon has a cucumber-like, fresh aroma, and the brightness of the lemon juice alongside the pop as we bite into each just-warmed pea transports us to a sunny early April day each time we eat this dish, even if it's actually a rainy day in November. Nearly any variation of avgolemono (the lemon juice, egg yolk, and broth-based soups found in Greece and throughout the Levant) evokes similarly springy sensations for us, but we like HAMILTON's version because it's easy-peasy and delightfully creamy. Ingredients for the salmon, serves 2-4 1 pound whole salmon fillet, pin bones removed, neatly trimmed, and skin intact 1 tablespoon extra-virgin olive oil 3 generous pinches coarse kosher salt 6 full grinds of a pepper mill 1 sheet parchment paper (brown is not recommended) Directions for the salmon 1. Preheat the oven to 375°F/190°C. 2. Lay a sheet of parchment on a baking sheet and place the salmon fillet skin-side down in the center. 3. Thoroughly coat the fillet and an inch or so of the surrounding parchment with the olive oil, creating a slick and glossy surface. 4. Generously and evenly season the fillet with salt and pepper. Hold your hands about eight inches above the fish when seasoning for more even distribution, thus avoiding salty or peppery patches. 5. Gather the parchment by both long sides and bring them together, folding over two or three small folds with a sharp crease, until you have a neat packet. Then fold the open ends two or three times in the same way, tucking them under the fish, thus creating a tightly sealed packet from which no steam can escape during cooking. 6. Place the packet on the baking sheet on the middle rack of the preheated oven and cook for exactly 10 minutes. Remove and, in good light, check the fish's color by peeking inside the parchment without fully opening it. It should be pale pink and opaque at the edges with a broad swath of still-translucent orange flesh down the center. 7. Return to the oven for about five more minutes, or until the rare-looking swath has narrowed to a half-inch stripe. Don't overcook it! 8. Remove the salmon from the oven. Very carefully, open the packet and release the steam to prevent further cooking. Ingredients for the creamy lemon rice 2 cups excellent, rich chicken broth 4 large egg yolks ½ cup fresh-squeezed lemon juice ½ cup frozen peas 1 bunch of scallions, sliced to yield a scant ½ cup of rings 2½ cups cooked rice (day-old is more than fine) 2 generous pinches coarse kosher salt, or to taste Directions for the creamy lemon rice 1. Bring the chicken broth to a simmer on the stove top in a stainless-steel pot and keep it simmering as you gather the rest of the ingredients. It will slightly reduce and intensify in these few minutes. 2. In a stainless-steel or glass heatproof bowl, whisk the egg yolks, then add the lemon juice and whisk until blended. 3. Add a ladleful of hot stock to the egg-lemon mixture and whisk thoroughly. 4. While whisking, slowly add the hot egg-lemon mixture into the pot. Stir or whisk gently over medium-low heat while the liquid ever so slightly thickens and changes color from bright to pale yellow, about two minutes. Add the peas and the scallions, which will turn bright green in the first few seconds as they blanch in the hot liquid. Stir gently until the peas are warmed through, then add the cooked rice. Stir thoroughly, then turn off the heat and let rest, covered for a minute or two. Season with salt and pepper as needed. 5. To serve, spoon the soupy rice onto a platter with a rim. Place the salmon on top and gently pull it apart into large chunks. Leave the skin stuck in the parchment. 6. Taking care not to spill, lift the parchment and pour the accumulated juices over the salmon on the rice. |

Table 3: Gabrielle HAMILTON's salmon with creamy lemon rice recipe4)

Figure 4: Lemony peas and rice with salmon [25]

GREENE's (1995a, 1995b) work complements FUIST's (2021) insistence on the necessity of imagination for intersubjectivity, going further to connect imagination and community with aesthetic encounters. GREENE argued that imagination enables empathy and the potential to see things that are otherwise invisible. She described aesthetic encounters as catalysts for seeing things in a new way:

"Participatory involvement with the many forms of art does enable us, at the very least, to see more in our experience, to hear more on normally unheard frequencies, to become conscious of what daily routines, habits, and conversations obscured ... To see more, to hear more. By such experiences we are not only lurched out of the familiar and the taken-for-granted, but we may also discover new avenues for action. We may experience a sudden sense of new possibilities and thus new beginnings" (1995b, p.379). [26]

Such experiences enable collective envisioning of "what should be and what might be" (1995a, p.5). GREENE's injection of ethics ("what should be," emphasis added) reflects what PERRIN (2006) called the democratic imagination: "What is possible, important, right, and feasible" (p.2). FUIST (2021) explained further that the democratic imagination is not a set of "society-wide, shared representations, but how people envision politics within groups, ultimately shaping how they understand their ability to take action" (p.363). SCrWE, we argue, is one means by which research teams may do that imaginative work. [27]

When we realized cooking school was more than just cooking school—when we realized it was helping us understand ourselves better as co-researchers—we sought to formalize our investigation of our experiences. We were inspired by CHANG, NGUNJIRI and HERNANDEZ's (2016) description of collaborative autoethnography. CHANG et al. defined collaborative autoethnography as "a qualitative research method in which researchers work in community to collect their autobiographical materials and to analyze and interpret their data collectively to gain a meaningful understanding of sociocultural phenomena reflected in their autobiographical data" (pp.23-24). Collaborative autoethnography's emphasis on collaboration, flattening hierarchies, and questioning individual and collective experiences resonates with our own research goals. Collaborative autoethnography also invited us to consider carefully the dual roles we occupied as participants and researchers in cooking school, leading to a nuanced understanding of our experiences and how they enabled us to better understand collaborative inquiry. [28]

Cooking school occurred during the 2016-2017 academic year. As we noted in the introduction, at that time, we were both doctoral candidates at a large research university in the United States; we had both completed the coursework portions of our programs and were writing our dissertations. In addition to cooking school, we were members of the same writing group. As members of that critical friendship group (COSTANTINO, 2010), we had (along with three other colleagues) conducted a study about collaboration and hedging in critical friendship groups like ours. When we began to examine and write about cooking school, we collected archival materials (i.e., menus, social media posts, photographs, text messages, calendars, emails) from the 2016-2017 year, and using these artifacts, we generated imperfect but evocative personal memory data (i.e., reflections and short writings from memory about our experiences). Simultaneously, we also generated self-observation data, including memos and writings about our own activities during the research process. These self-observation data, CHANG et al. (2016) pointed out, are distinct from "past-oriented data" in that they "capture your present actions and thoughts as they unfold before your eyes at the present time"; there is value, they write, in "jotting down your fleeting thoughts and actions in the present" despite the impossibility of recording "unadulterated" data about the present (p.77). We noted our individual responses to our collected data and how they merged and diverged from each other. Our data collection and data generation processes were iterative and ongoing. We shared our individual reflections with one another, probing for deeper meaning and then revisiting our initial understandings. Through multiple cycles of collaboratively examining the data, co-constructing meaning, and documenting our thoughts, we began to better understand the complexity of cooking school, a specific example of what we have come to know as SCrWE. Some readers may question the long period between cooking school and the publication of this article. This period was lengthened by our struggle to turn our findings into a text that captured the creative and playful aspects of cooking school specifically and SCrWE broadly. We wrote two nearly complete versions of this article before we realized that we needed to incorporate our recipes and photos, elements that we find necessary to indicate the ineffability of the creative, aesthetic experiences we shared, as we describe earlier in this article. In the following section, we share the outcomes of our SCrWE, but we welcome the expansion and refinement of this strategy by other researchers as they design, engage in, and study their own SCrWEs. [29]

|

Country captain—even the name of this dish conjures excitement and the possibility of adventure. Country captain is "a staple of Southeastern Junior League cookbooks"5) and common in the Low Country of Georgia and South Carolina. The dish first appeared in Eliza LESLIE's (1857) "Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book." She described it as an "East India dish" (p.300) and speculated that it was first introduced to English sailors (and their tables) by locally recruited members of the East India Company's army on the Indian subcontinent. The dish is essentially a mild and somewhat sweet chicken curry. Our favorite recipe (included here in its entirety) comes from Alex HITZ (2013) writing for House Beautiful and includes plump golden raisins and slivered almonds. As HITZ noted, there are many ingredients, and you should measure each one. We undertook this recipe as a challenge and loved it immediately. It is a bit of a project. It takes at least a couple of hours to prepare, and we recommend letting it simmer on the stove at the end for another 45 minutes or an hour. Other important advice: Prepare it the day before you intend to serve it, as the flavors benefit from more time to meld. Additionally, we encourage you to add the rice to individual dishes when serving; keeping the rice separate makes the leftovers more freezer friendly (and there will almost certainly be leftovers—this recipe makes a dozen or so servings). Ingredients 1 pound bulk pork sausage, mild 3 pounds boneless, skinless chicken breasts 2 pounds boneless, skinless chicken thighs 2 teaspoons plus 1 tablespoon salt, divided 2 teaspoons ground black pepper, divided 1½ sticks (12 tablespoons) salted butter, divided 3 cups medium-diced white or yellow onions 1 cup medium-diced red bell pepper 1 cup medium-diced celery 2 tablespoons minced garlic 1½ tablespoons dark brown sugar 1 tablespoon curry powder 1½ teaspoons dried thyme ¾ teaspoon ground cumin 2 teaspoons minced fresh ginger ¾ cup flour 2½ cups tomatoes, peeled (use good-quality canned ones) 5½ cups chicken stock 2½ cups white wine ½ cup lemon juice 1 tablespoon apple cider vinegar 2 cups golden raisins 4 cups cooked rice ¾ cup snipped chives 1½ cups toasted slivered almonds ½ cup chopped parsley 1. In a large, heavy skillet over medium-high heat, brown the sausage, fully breaking it up, and then drain off the excess fat. Reserve. 2. Wash the chicken breasts and thighs and pat them dry. Place them in a mixing bowl and toss with 2 teaspoons of the salt and 1 teaspoon of the black pepper. 3. In another large, heavy skillet over medium heat, melt 4 tablespoons of the butter. When the foaming has subsided, add the chicken and sear it in batches on both sides until it is brown on the surface but still raw inside, about three minutes per side. Remove chicken from the heat, let it rest for at least five minutes, and then cut it into approximately 1½-inch chunks and reserve it in a bowl. Do not worry that the chicken is still raw on the inside, as it will finish cooking later. 4. In a large, heavy stockpot over medium heat, melt the remaining 8 tablespoons butter. When the foaming has subsided, add the onions and sauté for three minutes, until they start to get soft. Then add the peppers and celery, and sauté for another three minutes. Add the garlic, the remaining tablespoon of salt, the remaining teaspoon of pepper, the dark brown sugar, and the curry, thyme, cumin, and ginger and continue to sauté these ingredients until the onions are translucent, approximately four to eight more minutes.Add the cooked sausage, then the flour, and stir the mixture thoroughly. It will become very thick. 5. Add the tomatoes, chicken stock, wine, lemon juice, vinegar, and raisins and bring the mixture to a boil. Reduce the heat to a simmer and continue to simmer for five more minutes. 6. Add the chicken and simmer the mixture for five more minutes, until the chicken is completely cooked through, and then turn off the heat. Stir in the cooked rice, chives, almonds, and parsley and serve it with buttered crusty French bread. |

Table 4: Alex HITZ's chicken country captain6) [30]

As we describe in our conceptual framework, our SCrWE (cooking school) helped us uncover and deepen ways of engaging collaboratively. When cooking—particularly when cooking complex recipes with many ingredients, such as a pot of chicken country captain—the concept of mise en place is vital: Before we light the fire beneath our saute pan, we take care to assemble and prepare our ingredients, review our recipe, and anticipate moments of hurry. We chop vegetables, arrange our spices and measuring spoons, and make sure we have ample clean bowls. Once cooking begins, we remain attentive to our recipe and notes; we taste, discuss, and make adjustments. Was the pepper we included a little hot or a little sweet? How dry was the wine? As we carry out this work and engage with one another, we deepen our understanding of one another's processes, palettes, and preferences, enriching not only our present experience but also future experiences. In other words, we engage in aesthetic experiential play, lingering in unanticipated possibilities, and, in their afterglow, imagine—perhaps even create—something new. In this section, we describe some of the specific outcomes of our SCrWE, including unearthing unconscious beliefs, developing intersubjective understandings, and engaging aesthetically and ethically, citing specific examples from cooking school. [31]

5.1 Unearthing unconscious beliefs

Research teams cannot reconcile unknown differences; in order to solve unanticipated problems (which will, certainly, arise), research teams require time, negotiation, and deep, nuanced understandings of themselves as individuals and team members. It is essential, then, that research teams create moments where latent preconceived notions, previous experiences, and taken-for-granted assumptions can surface. These experiences need not be designed like therapy sessions but can be similarly surprising and cathartic. For example, when we began planning cooking school, we did so pragmatically, thinking about elements such as the dishes we wanted to learn to make, where it would happen, and who would buy what each week. We did not anticipate, however, how differently we experienced the pedestrian activity of cooking.

Crystal: I began cooking school after several years of progressively expanding my repertoire of skills and knowledge about food and food preparation. The kitchen was a safe, happy space in my home where I exercised creativity as well as control. Although I knew Libba was less confident in the kitchen, I did not expect—nor did I understand until we had had several weeks of cooking school—the depth of her apprehension about cooking. [32]

When she was 18, Libba had accidentally started a grease fire, damaging not only her kitchen but her dominant hand. In the immediate aftermath of the fire, her care providers were not sure how much hand function she would regain, a terrifying prospect for anyone but especially an artist. While we were already good friends at the start of cooking school, we had had no opportunities for this significant kitchen-centered experience to come up.

Crystal: Once Libba shared this experience, I experienced a significant shift in how I understood Libba's reluctance to depart from a recipe as written and her hesitation about many kitchen tasks I regarded as perfunctory. Libba's hesitation was not simply a matter of feeling uncertain about trying something new: Her previous kitchen experiences had led directly to threats to her livelihood and most important means of personal expression. [33]

This realization fundamentally changed how Crystal planned activities for us and how she introduced new skills during our time together; it shifted the lens through which Crystal saw our work and her colleague and friend. This sort of realization is directly tied to our previous experiences as researchers. When working with research teams (and when working with participants), team members similarly bring to their work their own prior knowledge and latent assumptions about a variety of people, places, things, and ideas. Participation in SCrWE gives team members the opportunity to look through "new eyes" (GREENE, 1973, p.268). GREENE wrote that this kind of seeing is

"like returning home from a long stay in some other place. The homecomer notices details and patterns in his environment he never saw before. He finds that he has to think about local rituals and customs to make sense of them once more. For a time he feels quite separate from the person who is wholly at home in his ingroup and takes the familiar world for granted ... Now looking through new eyes, he cannot take the cultural pattern for granted. It may seem arbitrary to him or incoherent or deficient in some way. To make it meaningful again, he must interpret and reorder what he sees in the light of his changed experience. He must consciously engage in inquiry" (pp.267-268). [34]

Through SCrWE, researchers intentionally create moments where they may face one another's strangeness. Research partners are colleagues and frequently friends; in our experience, conceptual and practical elision is easy and common. SCrWE challenges participants to recognize one another as strangers, as described by AHMED (2000): "Somebody we know as not knowing, rather than somebody we simply do not know" (p.49). The stranger, AHMED continued, does not "[come] into being in an absence of knowledge" but is "produced as an object of knowledge" (ibid.). The stranger, in other words, is not represented by a gap or nothingness. Rather, the stranger is a particular subjectivity each human forms and assigns to one whose customs and culture are yet unknown. By implementing SCrWE, research team members—who may feel they already know each other well—create an opportunity to consider how they might also occupy the subjectivity of the stranger. What is unknown about thier partners? What is yet to be revealed? What is unknown or unrevealed to others about oneself? Researchers can begin to answer these questions through SCrWE. [35]

5.2 Developing intersubjective understandings

Beginning to see one another as strangers (i.e., as possessing as-yet secret or unrevealed qualities, experiences, and knowledge) precedes researchers' "co-construct[ing] realities of unconscious relational narratives" (CHILTON, GERBER & SCOTTI, 2015, p.5)—that is, the building of intersubjective understandings. These intersubjective understandings include superficial but necessary aspects of collaboration, such as finding a pace that works for all members of the research team, learning to share physical and digital spaces, and establishing a working shorthand when communicating about concepts and plans. For example, during cooking school, we gradually aligned our understandings of time (e.g., if Libba's session at the gym ran long, did she need to text Crystal to say she would be 10 minutes later than planned, or if it ended early, should she kill 15 minutes at the grocery store until cooking school's scheduled time?) and space (e.g., how many times was it necessary to say "excuse me" to one another in Crystal's tiny kitchen with limited counter space?). Over time, the answers to such concerns became obvious (and to the specific questions above: No, no, and not at all unless one of us was carrying a hot pan in which case the appropriate warning was "look out, hot pan!").

|

Ingredients 3 cups all-purpose flour plus more for dusting (durum wheat flour is great but not required) 6 large eggs 3 tablespoons olive oil Several generous pinches of kosher salt (Diamond Crystal brand recommended) 1 medium butternut squash, peeled, seeded, and cut into ½" cubes 1 pound sweet Italian sausage, ground (if your favorite Italian sausage comes only in links, simply remove it from the casings) 8 tablespoons (1 stick) unsalted butter, brought to room temperature Handful of fresh rosemary, removed from stem and roughly chopped 4-ounce log of goat cheese Work time: 1-2 hours Total time: 1.5-2.5 hours Start with a large, clear, uncluttered workspace. You will need plenty of room to knead and roll out your pasta dough. To make the dough, sift flour and a big pinch of salt onto your work surface. Make a well or bowl in the center of the flour. Crack the eggs into the bowl. Add a tablespoon of olive oil to the eggs. Use a fork to break up the eggs and begin to mix the wet and dry ingredients, taking care not to break the sides of your bowl until the mixture is thick enough not to cause an egg flood. When just combined, begin to knead the dough by hand. Dust your work surface with additional flour as needed. Kneading pasta dough is like kneading bread dough: Using the heel of your hand, push the dough away from yourself. Fold the dough in half, give it a quarter turn, and push again. Daydream. Fret a little if you must. Just keep pushing, folding, and turning until the dough is smooth and no longer sticky, about five minutes. Divide the dough into 2-4 equal balls, depending on the size of your work surface. If you have a larger work surface, you can divide the dough into fewer balls. Smaller work surfaces require working with the dough in smaller batches. Wrap each ball in plastic. Let the dough rest for 30 minutes. Don't worry: You have other work to do. Preheat the oven to 425°F/215°C. Peel, seed, and cube butternut squash (Figure 7). On a large sheet pan, toss squash with the remaining olive oil. Bake for about 45 minutes, shaking the pan halfway through to allow the squash to brown more evenly. While the squash roasts, brown the Italian sausage over medium heat in a large skillet, being sure to break it up into small pieces. I find it easier to drop the sausage into the skillet in small pinches rather than try to break it up with my wooden spoon after it begins cooking. When sausage is done, remove it from the skillet using a slotted spoon. Now is the time to enlist a friend. Unwrap your first ball of dough, and place it on a lightly floured surface. Lightly dust the top of your dough with flour as well. Dust your hands with flour, and use them to lightly flour a rolling pin. We like a long French rolling pin, but we can say from personal experience that a floured wine bottle can also work in a pinch. Using the rolling pin, push the dough away from you, making sure to turn the dough so that you roll it into a sheet of more-or-less uniform thickness.7) Patience is required, which is why we recommend a friend to roll next to you. Music, wine, and conversation are optional but strongly encouraged. Continue rolling until the dough is thin enough to see through. The dough should be supple and dry to the touch, like very fine, soft leather, not stretchy and prone to holes like pizza dough. You can use a pasta rolling machine or pasta attachment for your mixer for this step, too, but we recommend giving it a try by hand at least once. Once it's thin enough, let it dry on your work surface for about ten minutes. While the pasta dries, fill your biggest pot with water. Add several generous pinches of salt. Set over high heat. Remove your squash from the oven, and set it aside. Remove your goat cheese from the refrigerator. Now it's time to brown the butter. Cut your room temperature butter into tablespoons and add to a small (6" or 8") skillet with a light-colored interior so you can monitor the color of the butter as it cooks. Cook over medium heat, stirring as it melts. Once melted, the butter will foam and sizzle. Keep stirring, and soon the milk solids will separate from the liquid, settling at the bottom of your pan. These solids will toast into nutty, rich deliciousness; just be sure not to let them get too dark or they will taste burned. The whole process will take seven or eight minutes. When the solids are the color of walnuts, sprinkle the chopped rosemary in the pan, give it one final stir, and remove from the heat (McKENNEY, 2019, has excellent pictures to help you gauge when your butter is just right). Dust your pasta sheets lightly with a little more flour. Roll each sheet into a cylinder, like wrapping paper, and using a very sharp knife, cut into 1" pieces. Go even wider if you want—we love double-wide pappardelle! Gently unroll. You should have a big pile of pasta now. (And if you made more pasta than you planned, you can refrigerate or freeze some of it now.) Drop into the boiling water, stir gently to separate, and cook for one minute. Using a spider or large slotted spoon, transfer cooked pasta to a large bowl. Toss with squash and sausage. Drizzle with browned butter, and use your fingers to drop the goat cheese on top in small dollops. Toss everything together one last time, and enjoy with friends. |

Table 5: Pappardelle with butternut squash, sausage, and goat cheese recipe

Figure 5: Pappardelle with butternut squash, sausage, and goat cheese [36]

Ideally, research teams will come to share understandings of how power operates in the context of their common work and how to honor one another's contributions. These understandings are grounded in intersubjectivity. CHILTON et al. explained, "people co-create or construct meaning—what they consider to be significant, real or true—through dialectical and dynamic processes which involve these multiple interactive realities" (2015, p.7). In other words, research teams must do more than simply develop shared procedural knowledge. Our deeper intersubjective understandings became evident when we invited outside guests to cooking school. When working on this section of this article, we recalled specifically the evening we made pappardelle with roasted butternut squash, sausage, and goat cheese. Homemade pasta felt like a true event, so we invited our program colleagues, good friends, and occasional-cooking school guests Kate and Allie to join us that evening. The decision to invite them was shared. Over the course of cooking school, Crystal's kitchen had become—at least on Thursday evenings at 5pm—cooking school's kitchen. It was our space to negotiate and share as we desired. And when Kate and Allie arrived, we acted as cohosts, explaining and modeling cooking school norms and both taking on typical host tasks such as taking coats, offering drinks, and accepting the gifts of wine and dessert they had brought. While cooking, we engaged in our now-typical easy collaboration, dealing with the problem of not enough rolling pins by improvising with wine bottles and then reusing those wine bottles (some empty at this point) and our longest wooden spoons to create space to hang the long strips of pasta while we rolled and cut out more (Figure 6). We invited Kate and Allie to join these activities with little obvious negotiation about how to proceed, the intersubjective understandings of cooking school—including the necessary role of playful improvisation without shame—by then well established. While writing this article, we discussed the development of intersubjectivity with Kate and Allie, and they both immediately and independently mentioned pasta night as an example. Research teams likewise need time and opportunity to co-construct shared understandings in low-stakes contexts before negotiating and carrying out higher-stakes research activities such as designing a research project, interacting with participants, and writing for publication. In other words, if Kate and Allie had been participants in a research study rather than dinner guests, our ability to seamlessly invite them into our space and put them at ease would have been essential to the outcomes of our project. Research collaborators' intersubjective understandings—though they may be developed via seemingly superficial processes—are transferable to higher-stakes contexts.

Figure 6: Pasta night [37]

5.3 Engaging ethically and aesthetically

Cooking school afforded more than just a low-stakes collaborative environment: Within this context, we had to engage aesthetically and ethically, attributes we consider critical for SCrWE. Research teams must explore their values—that is, their axiological commitments—in order to affirm shared points and reconcile potential differences. According to WHITE, this activity must happen in the moment and with an object. "Valuation," WHITE (2009) wrote, refers to "the act of valuing, which is spontaneous and involuntary; not to be confused with evaluation, which is reflective" (p.47). He continued:

"there is a difference between value and experiencing that value in the form/content fusion of a gestalt. For example, we cannot point to courage, sadness or even beauty. Values need an object or situation from which to emerge. They are, in that sense, parasitic. That is why we say that sadness is in the story or beauty is in the sunset" (pp.47-48). [38]

Cooking school offered many such situations from which aesthetic and ethical values emerged. When reflecting on our experiences, one of our essential dishes—a dish that both of us can still recall with great detail and that we both made outside of cooking school many times and continue to make—was Martha STEWART's (2017a) chocolate pavlova (Table 6 and Figure 7). Pavlova is a dessert that is more common in Australia and New Zealand than in the United States. It is made of sugar and egg whites, like a meringue; STEWART's version also includes cocoa powder. A pavlova bakes low and slow in a large, single dollop, yielding a uniquely complex texture to the finished product: The center of a properly baked pavlova is gooey and marshmallowy while the edges become crisp and airy, like a meringue cookie. Topped with whipped cream, fruit, chocolate shavings, or Nutella, pavlova is simply divine. Making a pavlova requires careful attention at several points. The eggs must be beaten just to the point of stiffness; the oven must be just hot enough; the pavlova must remain undisturbed during baking but then come out at just the right time; and, perhaps most difficult, the pavlova must sit and cool before eating. While a well-written recipe is useful, making a pavlova requires that the bakers rely on their senses. As EISNER (2002) wrote,

"the kind of thinking required to create ... cannot be conducted by appeals to algorithms, formulas, or recipes. Even when the schema for the creation of forms is familiar, there is always significant uniqueness in the particular configuration, so that the formulaic use of such a schema is unlikely to achieve a satisfying aesthetic resolution. Somatic knowledge must be employed" (p.19). [39]

During cooking school, making pavlova required us to exercise our aesthetic sense in new, exciting ways; pavlova invited us to reconsider what we thought of when we imagined dessert. But making a pavlova also had ethical implications. Core to cooking school was our commitment to reduce waste and embrace frugality; to nourish our minds and bodies on a graduate-student budget. Our decision to try a pavlova was driven in part by the cache of egg whites in the freezer, left from yolk-heavy recipes such as pasta and pudding. It required no ingredients that were not already in our cupboard and after the initial steps, could be left on its own to bake and then cool while we worked on our main dish.

|

Ingredients For the Meringue 4 large egg whites, room temperature ¼ cup dark-brown sugar ¾ cup superfine sugar Pinch of salt ½ teaspoon pure vanilla extract 2 tablespoons Dutch-process unsweetened cocoa powder To Assemble Dark-chocolate cream (STEWART, 2017b) 1 ¼ cups heavy cream, whipped to soft peaks Milk-Chocolate Curls, for garnish Directions Make the meringue: Preheat oven to 300°F/150°C. Line a rimmed baking sheet with parchment. Draw an 8-inch circle on parchment, then flip. Mix whites, sugars, and salt in a mixer bowl set over a pan of simmering water. Whisk constantly until sugars dissolve and mixture is warm, about 3 minutes. Remove from heat, and whisk on medium-high speed until stiff peaks form, about 8 minutes. Beat in vanilla. Sift cocoa powder over meringue, and fold until barely any streaks remain. Using an offset spatula or a large spoon, spread meringue into a round, using circle as a guide. (Be careful not to spread out too much; meringue will spread more during baking.) Form a well in center, being careful not to spread meringue too thin. Bake meringue until dry to the touch, about 1 hour. Let cool on sheet on wire rack. Meringue will keep, covered, for up to 1 day. To assemble pavlova: Spread dark-chocolate cream evenly in center of meringue, leaving a 1/2-inch border from edge. Spread whipped cream over chocolate cream. Garnish with chocolate curls, and serve immediately. |

Table 6: Martha STEWART's chocolate pavlova recipe8)

Figure 7: Chocolate pavlova with chocolate ganache [40]

Research teams need similar opportunities to think together with embodied or somatic knowledge and to make axiological judgments beyond prescribed, predictable situations. According to EISNER (2002), "somatic knowledge, what is sometimes called embodied knowledge, is experienced in different locations. Some images resonate with our gut, others with our eyes, still others with our fantasies; artists play with our imagination" (p.19). Somatic knowledge enables people to "be tuned in and to make adjustments" (p.76). This way of engaging is essential in the arts because it enables humans to perceive subtleties, paying special attention to nuanced qualities and differences, and heighten their awareness of relationships. We argue here that this way of engaging is just as essential in social science research for the same reasons. EISNER (1998) wrote primarily about schools and argued that little of the curriculum allows students to make these judgments. The overworked space of academe similarly limits researchers' opportunities to do this axiological work, especially together. [41]

SCrWE is not unique in its inclusion of aesthetic knowledge: In addition to CHILTON et al. (2015), EISNER (1998) and HOFSESS (2013) have advocated for the role of the senses in participant-researcher relationships in the contexts of art therapy and art education research. SCrWE is unique, however, in its explicit focus on developing intersubjective aesthetic knowledge with the goal of improving research outcomes in all disciplines. In SCrWE, sustained, shared aesthetic experiences are essential. SCrWE invites participants to engage with one another with intentionality and attentiveness in order to develop shared understandings of the ontological, epistemological, axiological, and practical components of their work. [42]

As we wrote in the previous section, pavlova is a dessert with near endless possibilities: It can be flavored and topped in numerous ways, yielding a final product that can be straightforward or complex, bright and fruity or warm and chocolatey, refreshing or indulgent. Likewise, we envision SCrWE as a process that may happen in many ways and include novice and veteran scholars alike. We do not, that is, expect that every team will engage in cooking school as their SCrWE. We suggest the following principles when designing a SCrWE:

Team members should mutually agree to engage in SCrWE. Cooking school simply could not have happened if only one of us had decided to do it; agreeing to undertake this activity together was the foundation for the vulnerability and trust that developed.

SCrWE should incorporate one or more creative work activities with opportunities for somatic and aesthetic experiences. Even the best recipes require refining to accommodate for availability of specific brands or tools, humidity, elevation, and appliances as well as personal dietary needs and preferences; approaching such refinements requires participants to engage their minds and bodies.

Team members should consider geographic and temporal constraints, planning activities in which all members can engage (virtually or in person, as members' needs dictate). From the outset of cooking school, we had to agree not only to prioritize cooking school each week but also negotiate nuts and bolts like purchasing ingredients and scheduling start times.

Teams should allow ample time for the creative work experience itself as well as for individual and collective reflection before, during, and after the experience. As we note in Tables 1, 3, and 6, many recipes require time and patience: Many SCrWEs do, too.

Team members should share the intention of becoming better co-researchers via SCrWE. Although we did not set out to improve our research partnership through cooking school, we encourage researchers for whom this is a goal to make that goal plain to one another. [43]

SCrWE intentionally creates instability and uncertainty in a way that yields play, creativity, and collaboration. But these positive outcomes cannot emerge without an initial, consensual willingness among team members to risk vulnerability. Team members must remain committed to these principles throughout the SCrWE process in order to nurture exploration of their ontological, epistemological, and axiological understandings, which we noted earlier is essential for well-functioning collaborations. These domains align with the outcomes of our experiences during cooking school: Unearthing unconscious beliefs reflects the ontological domain, developing intersubjective understandings the epistemological, and engaging ethically and aesthetically the axiological. In Table 7, we include a more nuanced list of the commitments and questions SCrWE requires and elicits, organized around these domains. Again, we imagine that research teams will use these commitments and questions differently but encourage planning explicit opportunities and means for individual and shared reflection.

|

Domain |

Commitments |

Questions |

|

Ontology |

I will: Engage in activities that might not immediately seem relevant to my research. Be in the moment. Consider how this experience might be different from another perspective or role. |

I ask myself: Am I having fun? What did I anticipate about this experience? What didn't I predict? Is there room for spontaneity in this experience? Did I lose track of time? Is there something new here? Am I different as a result of this experience? How? Why? |

|

Epistemology |

I will: Pay attention to my own feelings, thoughts, and actions. Pay attention to others' actions and expressions of their thoughts and feelings. Investigate the underlying beliefs or experiences motivating my feelings, thoughts, and actions. Ask questions when my own and my colleagues' experiences seem different or when we disagree |

I ask myself: What am I feeling? Thinking? How did I come to feel/think this way? What actions am I taking as a result? What do my colleagues seem to be feeling and thinking? How did they come to feel/think this way? What are they doing as a result? Could I imagine experiencing this situation differently? How? How could I come to know better the perspectives of my colleagues? |

|

Axiology |

I will: Examine what I believe is important and right. Examine what I believe is beautiful or brings me joy and pleasure. Focus on my own and my colleagues' ethical and aesthetic experiences. Reflect on disagreements. |