Volume 25, No. 3, Art. 1 – September 2024

Relational Dynamics of Conducting Field Research During a (Global) Pandemic

Miriam Tekath

Abstract: In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, projects involving field research were largely restricted or modified due to the increasing complexity of their methodological and ethical realization. Despite the slowly increasing debates on the (im)possibility of field research during that time, the relational dynamics of field research activities during the pandemic have not yet been discussed in detail. I address this gap by using CLARKE's (2005) situational analysis to reflect on a seven-month field research stay in Senegal during the Covid-19 pandemic. By conceiving of the pandemic and myself as the researcher to be an integral part of the research situation, I analyze how the research situation was characterized by relational dynamics which were shaped by different lived realities of the pandemic (politics). Building on this, I show how the encounter of different pandemic-related experiences was accompanied by irritations, uncertainties and joking practices, but also politicized as conflictual dynamics in the research situation. These insights are crucial for understanding the relational dynamics of conducting field research during a global pandemic that was experienced locally. Furthermore, I provide insights into the analytical potential of using situational analysis for a reflexive engagement with field research.

Key words: field research; situational analysis; Covid-19 pandemic; research relations; Senegal

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Field Research and Different Lived Realities in the Covid-19 Pandemic

3. A Relational Approach to Field Research

4. Using Situational Analysis for Analyzing Research Situations

5. The Covid-19 Pandemic in the Research Situation

5.1 Face masks in the research situation

5.2 "Pandemic" politics in the research situation

5.3 Contesting vaccines in the research situation

6. Relational Dynamics of Field Research During the Covid-19 Pandemic

7. Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic shaped social and political dynamics on a global scale. While the pandemic is undoubtedly primarily a health-related concern, its socio-political impact is overarching as it "has affected virtually every aspect of life, for individuals, communities, nations, regions, and the international system" (AGOSTINIS, 2021, p.302). In numerous social arenas, new forms of interaction had to be found and continuously adapted to minimize the risk of spreading a disease that posed a major health concern in a rapidly changing environment (ANDREWS, CROOKS, PEARCE & MESSINA, 2021, pp.1-2). This social experience of the pandemic was significantly shaped by evolving political approaches, ranging from a populist and "cruel" indifference to Covid-19 related deaths (FARIAS, CASARÕES & MAGALHÃES, 2022) to the instauration and severe policing of lockdowns which globally restricted domestic and international possibilities of moving and interacting with others (ONYEAKA, ANUMUDU, AL-SHARIFY, EGELE-GODSWILL & MBAEGBU, 2021). Despite this variety of measures, the pandemic policies exacerbated the difficult situation of already marginalized groups on a global scale (AGOSTINIS, 2021; AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL, 2022; PAPAGARYFALLOU, 2021). The Covid-19 pandemic as a global phenomenon thus manifests in multiple political and social experiences (ANDREWS et al., 2021, p.2), and these different socio-political realities of the pandemic co-exist from a local to a global scale. While I personally had, for example, the privilege of continuing to teach my university classes online and receiving my salary, a university student revealed to me in an interview that only few study programs in Senegal were able to uphold virtual learning opportunities in the initial phase of the pandemic (I2406212).1) The university closures in Senegal resulted instead in the interruption of most students' studies (I280121; N3003212). The students' scholarships were even withheld afterwards in order to revoke the financial support which they had wrongly received for these months of university closure (N020221; N070221; I090221). [1]

These pandemic-related repercussions on socio-political realities also impacted academia in multiple ways. Next to the temporary closure of university campuses, the shift to digital teaching and the cancellation or virtual organization of conferences, entire research projects had to be readapted to the changing circumstances of the Covid-19 pandemic (LEE, 2020). In particular, research projects involving field research2) were strongly affected, as research travels, the immersion in a specific social field or simply closer contact to other human beings were often limited or even prohibited (IRGIL, KREFT, LEE, WILLIS & ZVOBGO, 2021, p.1499; SALIBA, 2021). Consequently, the methodological approaches of many research projects had to be adapted (JUNG, KOLI, MAVROS, SMITH & STEPANIAN, 2021, pp.154-155; SCHAD-SPINDLER, FRIDRIK & LANDAU-DONNELLY, 2023, §17-21). In addition, irrespective of a pandemic, conducting field research always requires profound preparation as well as ethical reflections on possible harmful effects. In the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, these ethical assessments reached a new level of complexity as new variables suddenly became pertinent to the reflection of adequate research methods and settings. This significantly reduced the already limited number of possible research activities (FITZGIBBON, 2023; IRGIL et al., 2021, pp.1511-1512; NEWMAN, GUTA & BLACK, 2021). In addition, patterns of social (inter)action were heavily impacted by the danger of disease transmission and the concomitant pandemic politics. This led to social encounters being characterized by insecurities, conflicts and (re-)negotiations of what kind of interaction was deemed appropriate (FITZGIBBON, 2023, p.17). Given that developing social relations (DENZIN, 2017, p.23) and engaging in personal interactions are considered to be crucial for "doing fieldwork" (LUPTON, 2021), field research methods had to be completely reconsidered during the pandemic (KHOO & KARA, 2023, p.4). [2]

Next to these ethical and methodological repercussions on the planning and realization of field research, research situations themselves were also impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic. Drawing on the theoretical foundations of symbolic interactionism and situational analysis, social interactions in situations can never be conceived independently from political dynamics or personal socialization processes (CLARKE, WASHBURN & FRIESE, 2022, p.10; DENZIN, 2017, p.7). They are rather highly interdependent and embedded in dynamic relations with "situated aspects" such as behavioral norms and rules (DENZIN, 2017, p.10) or political discourses, regulations and technologies (CLARKE et al., 2022, pp.6-7). Research situations are not exempted from these dynamics, as "it is evident that social research becomes a type of symbolic interaction. Role-taking must occur, meaningful symbols must be present, situations have to be available, and time has to be allocated for research" (DENZIN, 2017, p.23). From this methodological position, research practices do not only have a selective effect on the perspectives they reveal but also, as a form of social interaction, they have a co-constitutive effect on creating, changing and affecting the researched reality (FRIESE, CLARKE & WASHBURN, 2022, pp.100-101; DENZIN, 2017, p.23). In the Covid-19 pandemic, this relational dimension of research situations means that possibly different and situated experiences, socio-political positions or frames of interpretation related to the pandemic coalesce. This can strongly influence the relational dynamic in which research situations are performed and experienced (FUJII, 2018, p.3). The co-constitution of research situations thus presents an inherently relational and dynamic process and is highly dependent on the research methods involved (DENZIN, 2017, p.23; DÉPELTEAU, 2018). [3]

Building on a seven-month field research stay in Senegal in 2020 and 2021, I address here the relational dynamics of field research in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic. Which relational dynamics evolve in the situation of conducting field research during a (global) pandemic and how do these relate to different lived experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic? The situational and relational dynamics of research as such are rarely openly discussed and comprehensive accounts of research experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic are even more scarce.3) I will thus add to this discussion by employing a situational analysis (CLARKE, 2005) for the reflection of my ethnographic research in Senegalese Higher Education institutions. This mainly involved participatory observation and episodic interviews with university students. By using the theory/methods package of situational analysis, grounded theory methodology (GTM) was adapted to the interpretive turn in order to provide a methodological grounding for the inclusion of reflexivity, complexities and heterogeneous perspectives in the analysis of situations (CLARKE, FRIESE & WASHBURN, 2018, p.12). It was thus particularly well suited for analyzing the relational dynamics in research situations during the Covid-19 pandemic. On the basis of the empirical insights derived from the situational analysis, I argue that conducting field research during the pandemic confronts different lived experiences and leads to irritations, uncertainties, joking, as well as politicized and conflictual relational dynamics in research situations. The relational dynamics of field research are thus shaped by the Covid-19 pandemic in a way that a new relational reality emerges in research situations that is worth paying closer attention to. In addition, I will provide insights into the analytical potential of situational analysis for reflecting on research situations. [4]

In the following, I first give an overview of the repercussions of the Covid-19 pandemic on research practices with a focus on field research activities (Section 2). In a second step, I describe the specificities of a relational research approach, how it strengthens the focus on the relational dynamics in research situations, and why it is crucial for conducting research during the Covid-19 pandemic (Section 3). This will be complemented by an introduction to situational analysis as a well-suited methodology for reflecting on these relational dynamics in research situations (Section 4). Subsequently, I will provide a short methodical introduction into the mapping process of situational analysis and present a thick description of my field research in Senegal (Section 5). Building on this, I use situational analysis for analyzing how the Covid-19 pandemic entered the research situation and shaped its relational dynamics on the basis of differently lived experiences (Section 6). These results will be discussed in the conclusion in order to link the relational dynamics of conducting field research to the Covid-19 pandemic (Section 7). [5]

2. Field Research and Different Lived Realities in the Covid-19 Pandemic

The repercussions of the Covid-19 pandemic on research practices are manifold and highly dependent on the research discipline. Especially in social sciences, however, the pandemic can be conceived as a "turning point for methods and ethics" (KHOO & KARA, 2023, p.2). While the design of research projects and especially field research always requires careful preparation, their realization often goes along with shifts and adaptations which become necessary in the research process (JUNG et al., 2021, p.153). Shifts in research designs thus occur also independently of the Covid-19 pandemic, but are in both cases, unfortunately, rarely openly discussed. However, the few existing reflections of the repercussions of Covid-19 on research designs show that often the intended methods, sometimes even the entire methodological approach or research question, had to be adapted (SCHAD-SPINDLER et al., 2023; JUNG et al., 2021). In this section, I discuss the organizational, methodological, but also ethical implications of conducting field research during the Covid-19 pandemic against the background of different lived realities in the pandemic. I will also exemplify how these aspects concerned my own research. [6]

For research projects involving field research, the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic have been particularly strong, as contact and travel restrictions rendered a research stay and the process of getting personally embedded in a specific social field extremely difficult. SALIBA (2021) even expressed the fear that specific restrictions concerning field research, either from overcautious university administrations or politically concerned border authorities, will stay in place and hinder field research beyond the pandemic. The restrictions in organizing field research led to a particularly strong increase in digital research methods which attempted to enable "remote fieldwork" (IRGIL et al., 2021, p.1499). This shift in research methods was accompanied by different challenges and opportunities. [7]

The challenge of technically organizing digital research methods, sometimes even in different time zones, goes along with the hope that new empirical insights can be gained by employing such digital methodological approaches (JUNG et al., 2021). While the shift to remote fieldwork (IRGIL et al., 2021, pp.1513-1514), netnography or other digital research approaches (NEWMAN et al., 2021) might have been feasible for some, many research projects simply could not be carried out virtually due to their research focus or limited possibilities of virtual access to the field (SALIBA, 2021). In addition, access to internet and computers or other technical devices, and the knowledge and ability to use them is highly dependent on the socio-economic circumstances and individual capacities of participants (JANSEN-VAN VUUREN & N'JAI, 2021; SHIVE, DOORENBOS, SCHMIEGE & COATS, 2022, pp.59-60), making digital research impossible in many contexts. These inequalities are also relevant for research projects carried out within the framework of North-South collaborations, as equal access to technical infrastructure is crucial for the collaborations' success (SOWE, SCHOENFELD, SAMIMI, STEINER & SCHÜRER-RIES, 2022). [8]

Given this importance of equal access to and knowledge of technical infrastructure, the Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated already existing inequalities. This is also relevant with regard to the inclusion or exclusion of experiences and perspectives by these "new" forms of academic knowledge production (IROULO & TAPPE ORTIZ 2022, p.3; NEWMAN et al., 2021, pp.7-8). It leads to the ethical dilemma that using digital methods might worsen exclusionary dynamics in research processes but can also prevent research participants and researchers themselves from being exposed to a possible health risk or contributing to the spread of disease during the research process (KHOO & KARA, 2023, p.2). The dilemma becomes even more complex when considering that the benefit of both in-person and digital research during the Covid-19 pandemic needs to outweigh the possibly harmful costs of exposing participants in personal research settings to health risks (IRGIL et al., 2021, p.1512) and of overburdening research participants who already find themselves in a period of crisis (KHOO & KARA, 2023, pp.2-3). [9]

The complex ethical dilemmas related to the Covid-19 pandemic hence derive not only from epistemological dimensions of knowledge production, but also from the adaptability of research methods to the situational necessities of the research field (SHIVE et al., 2022, p.60). "Whether personal, local, or global, crisis disrupts our understanding of how to respond. Our tools no longer fit the task," FITZGIBBON (2023, p.18) argued in relation to this necessity of flexibly reassessing and adapting research methods to the changing pandemic situation. While digital methods are undoubtedly largely beneficial for conducting research during the Covid-19 pandemic, FRIESE (2023, §26-27) stressed that these might not be able to grasp the situational dynamic of embodied and affective experiences in the same way ethnographic research can. This criticism is, however, challenged since VON BOSE (2023) showed the extent to which affective atmospheres of virtual and in-person research situations during the pandemic were similar. [10]

Beyond the reassessment and adaptation of research travels, field access and methods, entire social fields changed in the course of the Covid-19 pandemic as new habits and rituals of interacting, working, or studying together emerged. This change of social fields was also pertinent in the case of universities since the basic capacity of teaching, learning and doing research on university campuses was affected (LEE, 2020). That was also the case for the Senegalese universities where I conducted my research. In February and March 2020, I was in Senegal for a first short field research stay, during which I established initial contacts and conducted interviews with university staff as well as political and civil society actors in order to gain a better understanding of the socio-political and conflict-related dimensions of the universities, and to facilitate my research access for a second, longer stay. While I was able to gain a first impression of the Casamance region, its conflict heritage and the Université Assane Seck de Ziguinchor (UASZ) during this first stay, I was not able to carry out my planned research at the Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar (UCAD) anymore. Two days before my first planned visit to the UCAD, Senegal's President announced the immediate closure of university campuses, which eventually persisted for six months. I left Senegal two days later, wondering how university life might change until I would be able to come back. [11]

During the following months that I waited before I could return for a second research stay in December 2020, my personal lived realities as well as the lived realities of the Senegalese university members were simultaneously affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, but in very different ways. Back in Germany, I encountered the new reality of close social interactions being discouraged by different measures such as physical distancing, working from home, limiting the number of people one was allowed to meet and later, wearing face-covering masks (BUNDESGESUNDHEITSMINISTERIUM, 2022). As universities rapidly shifted to online teaching and encouraging work from home, campuses and university towns were increasingly abandoned. However, in this phase of the pandemic, neither a real "lock-down," in the sense of restricting the possibilities of leaving one's home, nor a curfew existed. This stood in sharp contrast to the lived realities in Senegal, where during the first months of the pandemic, a curfew was introduced and people were fined when leaving their homes late at night. In addition, the universities, but also many informal sites of social meetings and exchanges such as market areas, were closed (CHAKAMBA, 2020). Most of the university students left for their home towns, to stay with close relatives or friends, waiting for the universities to reopen (I120621, N280221). The uncertainty of how and when the universities would reopen left the students in a prolonged state of "waithood" (HONWANA, 2012, p.4)4). While most of the university students were not able to continue their studies during the university closure (I280121), in a few study programs such as medicine, some virtual learning components were introduced (I2406212, N3003212). This brief summary demonstrates that the Covid-19 pandemic (politics) affected the lived realities in Germany and in Senegal in 2020, and especially in the universities, in very different ways. After outlining the relational dimension of field research in the next chapter, I will discuss in the following situational analysis how these different lived experiences of the pandemic shaped me as a researcher, the university students and especially the research situation in its relational dynamics during my subsequent research stay. [12]

3. A Relational Approach to Field Research

Following core assumptions of relational sociology (DÉPELTEAU, 2018, pp.18-19), research can be conceived as relational on the basis of its dynamic and interactive co-production as a social phenomenon. In this understanding, the relational dynamics of a research situation are constitutive for the research situation itself. While the relational dynamics of field research are conceptually discussed in their relevance for methodological and ethical dimensions, as will be shown in this section, this is not yet the case for empirical experiences of conducting field research during the Covid-19 pandemic. In the following, I therefore first demonstrate the value of a relational approach for ethnographic research in general as well as for the practice of interviewing in particular, and combine this with a methodical reflection of how I attempted to realize such a relational approach in my own research during the Covid-19 pandemic. [13]

By stating that "[w]e bring to research sites skills and talents associated with the research process, but that does not prepare us for the task of developing relationships with those at the research site," CEGLOWSKI (2002, p.21) reflected that conducting ethnographic research necessitates methodological knowledge as much as the ability to create social relationships. In this sense, the practice of ethnographic research can be conceived of as inherently relational (p.7). In contrast to the outdated perception of the ethnographic researcher as an objective external observer, without any stance in the research itself, researchers are personally embedded in the relational dynamics of a research situation. Taking into account and reflecting on a researcher's positionality renders ethnographic practice truly reflexive (DENZIN, 2017, p.11; DENZIN & LINCOLN, 2002, pp.1-3). Although this relational dimension is crucial to an ethical engagement with a research field and a key aspect of a feminist research practice (EDWARDS & MAUTHNER, 2002, pp.22-24), it may equally prove to be dangerous. When relationships are exclusively developed for the purpose of extracting data, the practice of "doing rapport" can rapidly turn into "faking friendship" (DUNCOMBE & JESSOP, 2002). While different methodological tools are used to facilitate the relationship-building in research processes, these can similarly become a detached or even abusive form of imitating a close relationship in order to facilitate field access or the personal disclosure of research participants (pp.110-112). The relational dimension of research situations thus contains different challenges and ethical dilemmas and strongly depends on the situational elements and methods used. Unsurprisingly, ethnographic research can hence also be conflictual (CHANDLER, 2006) and field research is deeply intertwined with global politics (LOTTHOLZ, 2017) as well as different forms of social discrimination, such as racialization (AHMED, 2023). [14]

The relational dimensions of research situations depend on the concrete methods employed and the durability of a research relationship (DENZIN, 2017, p.23). My research is based on an interpretive methodology in order to understand the experiences of and engagements with dynamics of peace and conflict within Senegalese universities by university members and especially students. I was aware of the importance of gaining in-depth insights into the socio-political dimensions shaping Senegal, the Southern Casamance region, the regional conflict over territorial self-determination and specifically the micro-cosmos of Senegalese universities, in order to analyze the meanings that are ascribed to conflict-induced and politicized social differences in universities. But due to the Covid-19 pandemic, I perceived as too risky my initial plan of conducting group discussions5) with university students (BOHNSACK, PRZYBORSKI & SCHÄFFER, 2009). In my ethnographic research, I therefore opted for combining the methods of participatory observation with episodic interviews, a form of narrative interviews which focus on a specific life-period (FLICK, 2011), in my case the episode of going to university. [15]

For the interviews, I employed a relational approach. This was especially suitable because it explicitly allows for respecting research participants and their social life worlds and facilitates an ongoing reflection of my own positionality in the research process (FUJII, 2018, p.1). Given that the concept of positionality not only encompasses diverse layers of social categorization but also the situational perception of its social, political or economic dimensions (p.17), it is always present in the research situation and continuously shapes the research relationship between researcher and research participants. Reflecting on positionality thus requires considering the research questions we ask, the research assumptions we have, as well as the research situation itself in its socio-political dynamics. This relational approach also allowed for considering the dynamics evolving between me as the researcher and the research participants, not only during the interviews, but during the whole process of creating and maintaining a research relationship, something FUJII conceptualized as working relationship: "Working relationships are negotiated between the interviewer and interviewee and are shaped by the interests, values, backgrounds, and beliefs that each brings to the exchange" (p.3). The different lived experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic are hence highly impactful for the creation of research relationships as well as the entire research process. On the basis of this relational approach to interviewing (ibid.), I also attempted to grasp the manifestation of the Covid-19 pandemic in the research situation and how it shaped the relational dynamics in the research and interview process in the ongoing reflection of my research. [16]

I implemented this relational research approach by different means. Most importantly, I tried to establish long-term research relationships. Spending a total of approximatively 11 months during several research stays between February 2020 and March 2022 in Senegal was key to forming lasting relations. However, even beyond my personal presence in Senegal, I still maintain contact to several of my interlocutors, sometimes on topics completely unrelated to my research, but sometimes also on current socio-political dynamics in Senegal and in the universities. These long-term research relationships allowed me to establish a good basis for a respectful and reciprocal exchange which provided me with the possibility of learning about my interlocutors' relevance systems and life-episodes over a prolonged period of time. With several of the university students, I only conducted interviews after months of having a research relationship, also because some were initially reluctant to participate in my research. This is not surprising, given that talking about conflict dynamics is characterized by secrecy and mistrust (N020320). In order to facilitate a good understanding of my role, and to enable my interlocutors to give informed consent to my research, I was as transparent as possible about my research, including an open discussion of the complexities of my positionality and professional status. This role complexity was enhanced by conducting research within the somehow familiar but also unknown environment of universities (SCHWEITZER, 2022). While being fluent in French, my outsider position also manifested itself in my accent and the fact that I only learned Wolof, the lingua franca within Senegalese universities, during my second, longer research stay. [17]

Discussing my positionality also entailed being open about the diverse privileges associated with it, which I particularly addressed with regard to my university experience of studying in a somewhat constant, predictable and secured environment as well as having the possibility of financially supported international mobility—in contrast to the experiences of my interlocutors. While being equally transparent about my personal financial struggles, the navigation of several jobs in addition to my studies and the insecurity of being able to secure student grants and scholarships to continue studying, I gained an increasing awareness over time of the extent to which these experiences were still different from Senegalese students' experience of social precarity, despite a complex system of scholarships. In addition, I often discussed with the university students my double position as university employee and PhD student: On the one hand being a university employee provided me with a certain financial security, which gained pertinence especially in the highly uncertain context of the pandemic. This positional difference was increased by my role as a university teacher, which sometimes moved me into a more authoritative and knowledgeable position in personal interactions. On the other hand, we discussed that as a PhD student, I was still in a learning position, similar to the position of the university students, especially as some of the university students were starting their PhDs later in the research process. Last but not least, I openly shared my personal experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic—of having to leave Senegal in spring 2020, the insecurity of my PhD research, as well as the experience of social distancing and virtual teaching—and, in this way, exchanged with my interlocutors about their very different experiences of the pandemic. [18]

This relational approach with the ongoing reflection of my researcher positionality was of particular importance against the background of the Covid-19 pandemic since the pandemic "presented a novel opportunity for every researcher to be both subject and object in the research process, and to question their own methods and ethics" (KHOO & KARA, 2023, p.3). My relational research approach during the Covid-19 pandemic therefore combined the creation of long-term and respectful research relations with a continuous reflection of the relational dynamics evolving between me and the research participants against the background of different lived experiences of the pandemic (politics). Next to this research reflection, the relational approach also allowed me to maintain a high sensitivity with regard to the conflictual heritage as well as to the diverse difficulties resulting from the social, political and economic dimensions of my research field, which is of particular importance for conducting research in conflict-affected fields (MILLAR, 2021) and vulnerable communities (MORGAN, 2021). Furthermore, I was able to remain aware of the diverse ethical considerations through this relational approach which are considered to be particularly important for field research on the African continent (ADJIRAKOR et al., 2021; THOMSON, ANSOMS & MURISON, 2013, pp.1-3). Given the colonial legacy of research and knowledge production, these ethical considerations as well as a continuous reflection of my positionality and the diverse privileges associated with it were of utmost importance to the research process. On the basis of this relational approach, I was hence able to reflect on the meaning of my personal emplacement in the social field (BRIGG, 2020). Besides, the relevance attributed to reflexivity in this relational research approach (FUJII, 2018, p.1) strongly relates to methodological discussions of subjectivity and (self-)reflexivity in qualitative research on how reflexivity can be used for academic knowledge production (BREUER, MEY & MRUCK, 2011, p.436). In this regard, the specific dimension of relational reflexivity refers to "the opening up to the Other's point of view, and thus to reflexivity in regard to the relationship with the Other" (DONATI, 2020, p.185). How this relational reflexivity can be addressed methodologically will be discussed in the following chapter on using situational analysis for analyzing research situations. Empirically, this will be further exemplified by the ensuing reflection of the relational dynamics in the research situation on the basis of different lived realities of the Covid-19 pandemic. [19]

4. Using Situational Analysis for Analyzing Research Situations

Research reflexivity played a crucial role for the differentiation of GTM and especially for the development of situational analysis (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.12). While GLASER and STRAUSS (1967) jointly laid the foundation for GTM, they developed respective methodological strands which differ, amongst other things, in their conceptualization of the researcher's position and previous knowledge in the research process (MEY & MRUCK, 2011, pp.17-19). GLASER put forward the positivist ideal of an invisible researcher who must avoid forcing theory development out of previous knowledge (2002, pp.6-7). In contrast to this, STRAUSS (1987, pp.11-12) in his approach to GTM, which was further developed by STRAUSS and CORBIN (1990, 1997), considered scholarly and experiential knowledge as being able to foster theoretical sensitivity. They thus took into consideration the interpretive role of a researcher in the iterative analytical process (CLARKE et al., 2018, pp.4, 27) and thereby pursued a stronger constructivist research focus which also built on STRAUSS' formation in symbolic interactionism (MEY & MRUCK, 2011, pp.13-14). Being STRAUSS' student herself, CLARKE's (2005) theory/methods package of situational analysis, which she further developed in recent years together with FRIESE and WASHBURN (2018), strongly built on Straussian GTM and its ontological and epistemological roots in pragmatism and symbolic interactionism (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.24). Central ontological claims put forward by the Chicago school and symbolic interactionism (e.g., BLUMER, 1969; MEAD, 1962 [1934]), such as the social construction and situatedness of perspectives as well as the contingency of interactions, are thus key to situational analysis (CLARKE et al., 2018, pp.25-26). This concerns equally the perspectivity of the researcher in the research situation:

"we all come to our research with some prior ideas about it based on a range of experiences [...]. To us such prior knowledge, perspective, and experiences should not be denied but instead examined through the lenses of abduction and reflexivity" (p.31). [20]

The tendency in (mostly Glaserian) GTM to negate the researcher's active role and thereby also the concomitant accountability in the research process is therefore clearly rejected in situational analysis. Instead, the researcher is considered to be an integral part of the research situation, which indispensably requires a strong research reflexivity (BREUER et al., 2011, pp.436-444). In situational analysis, research reflexivity is thus of utmost importance for taking power dynamics into consideration and rendering the researcher accountable for what happens in the research process (CLARKE et al., 2018, pp.34-35). [21]

This emphasis on research reflexivity is one important dimension of adapting GTM to the interpretive turn which presents the central motivation for developing situational analysis (p.25). The interpretive turn is a description for the multiple methodological reactions to substantial crises and paradigm shifts in qualitative research, such as the crisis of representation or postmodern theories, for which a reflexive research practice is essential (DENZIN & LINCOLN, 2017, pp.9-12). In situational analysis, the methodological adaptation to the interpretive turn builds on key insights from feminist and power-critical theories (CLARKE et al., 2018, pp.10-11): For example, inspired by HARAWAY's (1988) important feminist contribution on "situated knowledges," the researcher's knowledges in a research process are always considered to be partial. Furthermore, (academic) knowledge production is considered to be strongly intertwined with power relations and thereby to bear the danger of reinforcing simplifying discourses (FOUCAULT, 1972 [1969]). In situational analysis, this danger should be overcome by taking "difference(s), power, contingency, and multiplicity very seriously" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.33). The tendency of oversimplification is thus addressed by studying the meaning of differences situationally and explicitly highlighting complexities and contradictions (pp.38, 51-54). As already outlined above, this can be achieved, for example, by employing a strong research reflexivity from the initial elaboration of a research project to the final analysis as well as by taking marginalized or silenced positions in the situation of inquiry into account (pp.34-38). [22]

Next to these important theoretical adaptations, situational analysis has been developed with the intention of overcoming the last "remaining positivist recalcitrancies" in GTM (p.23) by shifting its analytical focus from human action, the "basic social process" (p.4), to the situation (p.27). This analytical shift stands in contrast to the conditional matrices with which STRAUSS and CORBIN (1990) attempted to visualize and analyze how social structures influence social action. Given that social structures were still conceived to be external to social action in the conceptualization of conditional matrices, this hierarchization of social action over social structure is criticized in situational analysis (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.43). Instead of differentiating between a research unit and its context (p.17; see also CLARKE & KELLER, 2014, §75), the relational co-constitution of a phenomenon by all entities involved is a key assumption in situational analysis. In this understanding, "the conditions of the situation are in the situation" and if distinctions between elements are made, these should derive empirically from the perspectives of the actors and discourses in a situation (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.46). Taking situations as the principal unit of inquiry can hence not be equated with a temporal understanding of a short time period or a spatial limitation to one locality. Instead, a situation presents an "enduring arrangement of relations among many different kinds and categories of elements" (p.17). This emphasis on the relational character of situations also includes the research practice (CLARKE et al., 2022, pp.6-7, 10): "Research itself is a form of action in a situation" (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.42). Taking inspiration from science and technology studies, situational analysis simultaneously conceives non-human actants or technologies as potentially important elements in a situation (p.76). Similarly, building on the conceptualization of discursive formations in poststructural theories (FOUCAULT, 1972 [1969]), situations have agency beyond the knowing subject and the inclusion of discourses as a situational element presents an important addendum for analyzing power relations (CLARKE et al., 2018, pp.70, 80-81). Given this strong emphasis on the situatedness of social phenomena, situational analysis thus allows for conceiving the Covid-19 pandemic as well as the researcher as an integral part of the research situation itself. [23]

The conceptualization of the situation of inquiry in situational analysis is hence inherently relational. However, against the background of the multiplicity of possibly relevant elements, the situation of inquiry requires a delineation by "meaningful boundaries" during the analytical process (p.118). This can be achieved through the different analytical mapping strategies of situational analysis and their ongoing reflection in memos: First, all elements present in a situation are collected in situational maps. While in early conceptualizations of situational analysis, relational mappings were integrated into this step, more recent accounts of situational analysis present the creation of relational maps as a second mapping strategy on its own terms, as it analyzes the complex relations between the elements (CLARKE et al., 2022, pp.12-13). These two mapping strategies are complemented by the third strategy of social worlds/arenas mappings, which show the negotiations between and discursive construction of collective actors, and the fourth strategy of positional maps illustrating the main discursive positions taken and not taken in a situation (CLARKE et al., 2018, pp.17-18). In all of these four mapping processes, multiple maps are created, continuously adapted and reflected upon throughout the analytical process. On the basis of these mapping exercises and reflections, the "meaningful boundaries" of a situation can be identified by narrowing down which elements make a difference in the situation (pp.116-117). [24]

This conceptualization of the situation results out of the claim that situational analysis strengthens the methodological roots of Straussian GTM in pragmatism and symbolic interactionism and further includes postmodern theories in order to refine it for research after the interpretive turn (pp.50-51). Situational analysis is thereby an important methodological endeavor for including reflexivity, complexities and heterogeneous perspectives into qualitative research (p.12). For the purpose of analyzing the relational dynamics emerging from the co-constitution of a research situation during the global Covid-19 pandemic, this methodological emphasis on research reflexivity, a power-critical research approach and relationality appears to be particularly fruitful. Situational analysis is thus an important addition to the relational research approach outlined above and provides a methodology for how these relational dynamics can be analyzed. The following analysis will be based on a relational mapping which is best suited for illustrating the relational dynamics of conducting field research during the Covid-19 pandemic and thereby for providing an answer to the research question. Furthermore, by conceiving of myself, the researcher, as an integral part in the situation (CLARKE et al., 2022, pp.6-7, 10), the relational mapping was key for reflecting upon the relational dynamics in the research situation. Next to illustrating the complexity of the relational dynamics in the research situation, the relational mapping was thus also an important technique for enhancing my personal research reflexivity (BREUER et al., 2011, pp.437, 444). [25]

5. The Covid-19 Pandemic in the Research Situation

In the following, I will analyze the process of conducting research in Senegalese universities during the Covid-19 pandemic and the relational dynamics emerging in this research situation on the basis of field diary notes, notes from informal conversations, interviews and interview reflections. I collected this empirical material during my second research stay in Senegal from December 2020 to July 2021, during which I was mostly conducting research at the UASZ and later, after I received my first vaccination shot, also at the UCAD and the Université Gaston Berger (UGB). For the analysis of this research experience, I employed a situational analysis for which I initially collected all relevant elements in a messy situational map in order to subsequently analyze their relations in a relational mapping process (CLARKE et al., 2022, pp.12-13). Both steps were accompanied by an ongoing reflection of the elements' relevance in the situation and their relational dynamics, which I documented in memos. In Section 5 below, I will provide detailed insights into conducting field research during the Covid-19 pandemic in the form of a thick description. The thick description serves as a means for making the empirical foundation of the mapping presented in Section 6 understandable. While all relevant elements in the research situation are going to be contextualized and emphasized in italics, in the following Sections 5.1 to 5.3 I will particularly focus on face masks, "pandemic" politics and the Covid-19 vaccination. In a second step, the relational dynamics of the research situation will be analyzed in detail along the relational mapping in Section 6. [26]

The decision to continue my field research despite the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic was definitely not easy and entangled with several ambivalent relational reflections. While my personal financial situation and the time-pressure due to an expiring research bursary and limited contract terms were of course important factors in my decision to continue my research, I would not have made the same decision without the experience of my first research stay before the pandemic. The on-site insights and interlocutors I met during my first research stay in February and March 2020 helped me greatly in navigating the dilemma of deciding to go on field research during the pandemic. Being aware of the need for situated ethics when conducting research in conflict and crisis-affected educational institutions (CREMIN, ARYOUBI, HAJIR, KURIAN & SALEM, 2021), I reflected on what kind of situation I could and should expect to encounter in the Senegalese universities. From my previous research stay I knew, for example, that within the UASZ I could have access to a well-aired personal office and that the campus provides many shadowy and well-aired sites for meetings outside the buildings, which would allow me to maintain a physical distance during research interactions. In addition, my interlocutors within the university assured me that since the reopening of universities in Senegal in September and October 2020, university life on campus had returned to pre-Covid-19 times. As the pandemic had been attenuated in the Southern Casamance region in Senegal, I learned that there would be no barriers from the university administration for carrying out my field research. At the same time, I became aware of YouTube-videos showing how well the universities adapted to the pandemic by installing hand washing utilities and requiring face-masks on campus. [27]

This fostered my impression that there could be relatively "safe" ways of conducting field research despite the health-risks of the pandemic. In addition, I became increasingly aware that my interlocutors' lived experiences of the pandemic in the Casamance were not necessarily health-related, but rather shaped on an economic and political level. The political regulations (curfew, closure of university campuses, etc.) within the country were exclusively seen as an opportunity for corrupt police officers to enrich themselves, whereas international travel restrictions were understood as harming the domestic economy, which is highly dependent on tourism (N261220). Several of my early interlocutors, including university members, lost their formal or informal employments, which motivated me even more to spend my research bursary in the region. As my scholarship provider simultaneously obliged me to leave on field research before the end of 2020 in order to keep the bursary, I had to convince the German university administration that the research stay was actually possible and that there might be ways to "safely" conduct field research. Due to the pandemic situation worsening in Germany, the reality of Senegalese universities differed strongly from the conditions at my home university. This made it quite challenging to convince the university administration to authorize my research stay in Senegal. It was the first, but certainly not the last, moment during which I was confronted with and had to translate different lived realities during the pandemic. However, my on-site insights into the situation at Senegalese universities helped me to decide to leave for field research when I eventually received the permission to do so. [28]

After my arrival in Senegal, my understanding of the pandemic reality improved, as I could recalibrate many assumptions by engaging more closely with the experiences and perspectives of my social networks and the difficulties they experienced during the curfew. Simultaneously, I was constantly confronted with the ways in which the pandemic had affected me and my research performance, as I had to transition from months of physical distancing to suddenly actively seeking contact and creating research relations, while at the same time trying to keep myself and my interlocutors safe from any kind of disease propagation. The various protective measures that I had learned and applied, sometimes even unconsciously while experiencing the pandemic in Germany, like keeping physical distances to other people, putting on my face mask in crowded areas or avoiding closed spaces, suddenly took on a different meaning. This was the case within, but also beyond the university campus of the UASZ. [29]

One striking example occurred to me on one of my first days of the research stay in a side-street of the market area, where I put my mask on due to the narrow space. I was immediately called out by an elderly woman stating "We don't have corona here, it only exists in the North" (N201220)6), leaving it to my own interpretation whether she referred to the Northern part of Senegal (as the capital region around Dakar officially had the highest infection rates), to the divide of Northern and Southern territorial identities (which have been enforced during the 40 years of the Casamance conflict), or my positionality as a White person from Europe and the Global North (where the official infection rates outnumbered the rates in Senegal by far). In fact, during the whole research stay, I was confronted over and over again with these three frames of interpretation, according to which the disease was located elsewhere and the pandemic was interpreted in political terms. [30]

Once I arrived at the university, I quickly gained a better impression of the complexity of handling the pandemic within the UASZ. While being overwhelmed by joy and excitement to see a lively campus, close social interactions and even crowded lecture halls, I also understood that the formal and informal practices of physical distancing and mask wearing differed a lot (N040121). The nostalgic joy about a "normal" campus life was thus quickly mixed with worries about the pandemic dynamics within the university, and I was questioning if I would feel safe when engaging in closer interactions. These uncertainties did not just disappear after the first few days, but accompanied me constantly throughout the research process, in varying intensities. Below, I will analyze in more detail three elements which highlight how the Covid-19 pandemic became salient in the research situation. [31]

5.1 Face masks in the research situation

In my first interview during the Covid-19 pandemic, I decided to wear a face mask, while the interviewed student did not. In the beginning, I did not think wearing a face mask would matter much, considering I had been used to wearing one for months in Germany. In addition, I gave specific attention to discussing with my interlocutors beforehand how to best create an interview environment so that everybody felt comfortable. I thought that this co-determination of the interview setting was the best option ethically. However, the covering of my face and thereby the invisibility of my facial expressions, led to numerous irritations during the interview. My hopes of facilitating an initial narration of the experience of going to university diminished when seeing my interview partner becoming increasingly irritated, despite my previous attempt to explain how the episodic interview works. Diverse non-verbal signs or facial expressions which could have signaled my attention or showed my emotional response during the interview were not visible to my interview partner. I could therefore not perform as an active listener, which led to several interruptions and moments of uncertainty during which my interlocutor did not seem to be sure how I received the responses (NI280121). [32]

Luckily, as we established a long-term research relation after the interview, I was able to ask the student several weeks later how it felt to be interviewed by me wearing a mask. I learned that he was unfamiliar with having entire conversations while wearing face masks, as he usually wore a mask only for the guardians' controls at the entrance to the university campus to comply with the university's regulations. Following the student's interpretation, the pandemic was not really a relevant health issue in Senegal, since other diseases had higher mortality rates but were not a political priority. To him, all Senegalese measures to prevent the spread of the pandemic, such as closing the university campuses, imposing a night-time curfew, using hand sanitizers or face masks, were simply copied from France, as the Senegalese President Macky SALL wanted to impress the former colonial power with a strong and rapid political control of the pandemic. Many Senegalese made fun of this post-colonial dependency on France by calling their President "Mackycron"7). In this sense, my "measure" of wearing a mask during the interview appeared to be inappropriate as well, as "there is no corona at the university" (I280121). Our interaction during the interview was therefore marked by uncertainties and irritations which luckily did not lastingly shape our research relation. Instead, the long-term research relation helped to openly address these relational dynamics at a later time. [33]

5.2 "Pandemic" politics in the research situation

While I was able to adapt my initial interview practice by conducting interviews outdoors without a face mask whenever possible or by openly addressing the conversational impact of me wearing a face mask during interviews in the office, I still had to decide situationally how to perform my research in a safe and ethically justifiable manner. When I was invited to cook dinner with a group of students, I was unsure if and how I could navigate the invitation because I dreaded being in a small, closed room with several people, but wanted to use the opportunity of meeting the students in an informal setting. I feared that they would not necessarily be open to my pandemic-related concerns, as they had been joking about or commented on my face-covering or distancing behavior before. I eventually decided to simply gain a first impression of the place and to then decide if I would find it ethical to stay. I was relieved to see that the cooking area was well-aired and that only a few students participated in the dinner preparation. I thus took part regularly in cooking dinner with the students in this comparatively safe environment and felt even more comfortable doing so after having received my first vaccination shot. [34]

These dinner meetings took place almost every Sunday and allowed me to discuss a huge variety of topics casually with a rather constant group of students. In contrast to my interviews, the students determined the topics they wanted to discuss and from time to time, they also addressed their experiences and perspectives regarding the Covid-19 pandemic. They shared that in most of their study programs, many fellow students were still missing because they did not return to campus after the reopening of the university (N180321; N260321; N290521) and that events and meetings organized by the student associations, which strongly shape the socio-political university life, were still forbidden, supposedly due to the pandemic (N210221). Even after the reopening of the university, the pandemic situation was therefore still shaping the students' campus life. But instead of understanding it as a health-related matter, the impact of the pandemic was experienced in mainly political terms: The reduction of student numbers in the already overcrowded study programs was considered to be both an advantage for the university administration, as well as a restriction of the students' political power. This was perceived as highly problematic, especially as student protests had just occurred in relation to the reduction of students' scholarship payments. Many students received reduced or no scholarships at all because the university failed to clearly communicate that the amounts received during the pandemic-related university closure would be deducted from subsequent scholarships (N020221; N070221; I090221). This contributed to the students experiencing the pandemic even more in political instead of health-related terms—a perception which was additionally fostered by the experience of global pandemic politics, which I will further explicate in the thick description of a third element. [35]

5.3 Contesting vaccines in the research situation

When vaccination shots against Covid-19 slowly became accessible, I at first rejected the idea of getting vaccinated in Senegal to avoid taking advantage of the few vaccines available. But when Senegal's President Macky SALL reacted to the low vaccination rates by threatening to transmit the vaccines to "other African countries in need" (NAR GUÈYE, 2021), I thought that I might feel relieved to get vaccinated, because I would then at least be able to better protect myself and my interlocutors. I eventually received my first shot of a Covid-19 vaccine in Senegal in May 2021, and it affected my research process significantly in several ways. After suffering from strong side-effects of the vaccination for two weeks, the topic of the vaccination itself but also of the global politics surrounding it became directly relevant for my research process. Most of my research relations had already been well established for months, so I shared my experiences of getting vaccinated and falling sick due to the side-effects and received different reactions to it. One of the most striking subsequent interactions was a student challenging me a few weeks later in a joking but still concerned way that he just recovered from a few days of illness which he contracted after he visited me in my office the week before. Since he knew that I had fallen sick after my vaccination, he confronted me with the accusation of having propagated my vaccination to him against his will when he came to my office, which then caused him to fall sick as well (N290521). We subsequently had a long discussion about how vaccines and disease propagation work, but also about my own insecurities of performing my research in a "safe" manner and how this related to the pandemic. While joking about my face masks and physical distancing beforehand, the student suddenly uttered the accusation that I put him and other students at risk because of the vaccination. [36]

Even if I was surprised by this contestation and especially the fact that concerns arose only after I got vaccinated, I already knew the student and Senegalese joking relationships (DE JONG, 2005) quite well. This helped me to understand the interaction when I reflected on it afterwards, rather as a way of testing our research relation instead of a severe ethical concern or accusation. The same student had already tested my reactions to new or challenging circumstances beforehand, and my interpretation of this specific research interaction is that he wanted to see how I would react when being confronted with this criticism of my research ethics. In this specific situation, my positional difference as a White female and European PhD researcher with very different lived experiences but also political positionings related to the pandemic was actively stressed and my practice of conducting research during a pandemic challenged. For the student, this did not necessarily serve the purpose of preventing me from getting further vaccinations, but rather to see how the contestation would affect our research relation. [37]

6. Relational Dynamics of Field Research During the Covid-19 Pandemic

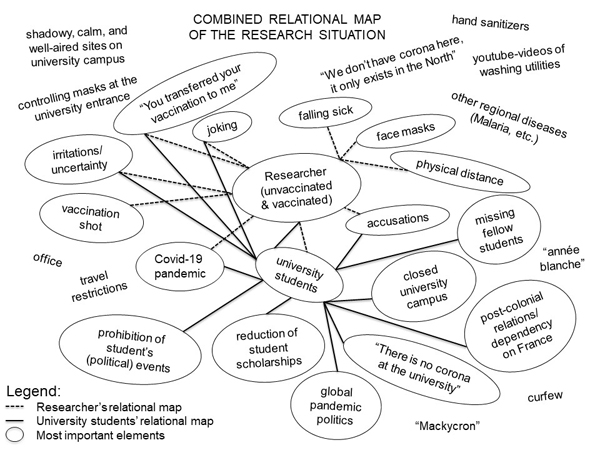

With the previous thick description of conducting field research during the Covid-19 pandemic, I attempt to stress the situationally relevant elements and thereby to reveal how the pandemic was an integral part of the research situation itself. In the following, the relational dynamics evolving out of this research situation will be analyzed in detail on the basis of a relational mapping which builds on reflecting upon and drawing out the relational embeddedness of singular elements (CLARKE et al., 2022, pp.12-13). While a relational map allows for understanding the elements' static relational configuration in the research situation, it cannot visualize the concomitant relational dynamics, which will be explicated in this section. For the purpose of this article, I decided to limit the present analysis to two particularly important relational mapping processes, i.e., the mapping centering the university students as main interlocutors and the mapping centering myself as the researcher. In Figure 1 I present a combined map of these two relational mappings, in which the students' relations are shown by straight lines and my personal relations by dotted lines. I combined the two relational mappings into one in order to better illustrate the extent to which the relational embeddedness in the research situation varies from different positional perspectives. In addition, the elements which mattered most in the research situation are encircled (CLARKE et al., 2018, p.141), but all of the elements emphasized in italics in Section 5 are part of the visualization.

Figure 1: Combined relational map of the research situation [38]

As outlined in Section 5, the Covid-19 pandemic manifested in the research situation in multiple ways and shaped its relational dynamics accordingly. For myself, the experience of the pandemic in the research situation was mostly related to the continuous adaptation of my research methods and the new complexity of ethical considerations. Both evolved with the different phases of the pandemic, new knowledge about the disease propagation as well as the development of vaccines. This strongly shaped my use of face masks, physical distancing and the choice of receiving my first vaccination shot. In my situational position as the researcher, these elements were on the one hand important for my self-identification and outside presentation as an academic committed to ethical standards and awareness for the various criticisms concerning field research during the pandemic. On the other hand, these considerations made me highly dependent on face masks and physical distancing practices and my relation to these elements evolved when I increasingly perceived them as an impediment to creating confidential research relations: While wearing a face mask and having face-to-face meetings inside my office assured a higher confidentiality, they also created a higher risk of disease transmission and limited non-verbal communication. At the same time, outdoor meetings were less confidential and could be easily interrupted by external events or persons. Next to these dynamics, my relation to the vaccination similarly shifted from perceiving it as a facilitator for conducting research to fearing it might cause (political) conflicts in the research situation. [39]

This strong focus on the methodical and ethical implications of my research during the pandemic, especially my practice of mask-wearing and physical distancing, initially blurred my awareness for my interlocutors' relational embeddedness in the research situation. While I was aware that the pandemic in Senegal was experienced in socio-economic and political rather than health-related dimensions, I underestimated what this would mean for my interlocutors' experience of the relational dynamics in the research situation. With my ongoing research reflection as part of the situational analysis, I increasingly became aware of how strongly their crisis experiences differed from my personal lived experiences. For the university students, the pandemic manifested first in closed university campuses, and after their reopening, in the prohibition of organizing political events on campus and reduced scholarships. These elements stand in a restricting and suppressive relation to the students as they limit their possibility of studying, their freedom of political expression as well as their financial security. Furthermore, the relation to their missing fellow students after the reopening is simultaneously characterized by dynamics of care and insecurity, because the university students had been trying to reach their former classmates but also experienced how quickly the pandemic could put an end to their studies. Finally, the students perceived the pandemic to not be directly relevant to their life at university, but rather as being related to Senegal's dependency on France and global pandemic politics. This resulted in their rejection of local and global pandemic politics, interpreting them as a form of post-colonial dependency and oppression. [40]

This reflection exemplifies that the relational embeddedness in the research situation differs visibly when being analyzed from different positional perspectives. The strong difference between the university students' and my personal relations as the researcher is visualized in Figure 1 and becomes evident in the combination of both relational mappings and the fact that most of the dotted and straight lines relate to different elements. While these different forms of relational embeddedness in the research situation go hand in hand with the relational dynamics analyzed above, they create a shared research relation which is characterized by three important dynamics: First, as outlined in Section 5.1, the research relation was continuously characterized by irritations and uncertainties with regard to my pandemic-related safety practices and their meanings in the research situation. After these uncertainties had slowly gained my attention, I was confronted with the fact that I had erroneously assumed that the student and I had co-determined the interview setting together. I slowly realized that I had underestimated the impact of my power position on the research relation and that this practice strongly emphasized my outsider position in the research field. Given my insufficient reflection on the implications of wearing a face mask, the irritations and uncertainties were fostered by unequal power relations in the determination of the research situation. [41]

Second, the research situation was also characterized by joking dynamics, which unfolded around the different pandemic-related experiences and practices. These joking dynamics can be understood as a way of coping with uncertainties and irritations. As a "practice predicated upon difference [which is embedded] into a discourse predicated upon sameness" (DE JONG, 2005, p.406), joking relationships present an important social practice for engaging with the different experiences of the pandemic while upholding the research relation in the commonly shared research situation. [42]

Third, the research relation is also strongly characterized by dynamics of politicization and conflict. In all three of the detailed descriptions of pandemic-related elements in Section 5.1 to 5.3, an entanglement with the political dimension of the different lived experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic became apparent, as it was continuously used as a point of reference: In Section 5.1, I described how by interviewing a student while wearing a mask, this was directly related to the post-colonial influence on Senegalese politics and the dominance of European lived realities which were conceived to be completely detached from local realities. In Section 5.2, I exemplified that the pandemic management within the universities was mainly perceived in political terms on the basis of missing students, reduced scholarship payments and restricted student events which lower the costs and the risk of further strikes. In Section 5.3, I underlined how by getting vaccinated during the pandemic, global pandemic politics and conspiracy theories gained presence in the research situation in the form of an openly conflictual accusation. This last example is particularly interesting in its relational dynamics, as I interpret it not only as an open contestation of my research practice and ethics but also as a way of testing the research relation itself in order to see if it can be upheld beyond the background of the different lived experiences and interpretations of the pandemic (politics). [43]

The research situation and the concomitant relational dynamics were thus significantly shaped by the different pandemic-related experiences. On the basis of the relational situational analysis in this section I revealed the extent to which the relational embeddedness of the university students and myself as the researcher in the research situation differed. This was also illustrated by the combined relational map in Figure 1. Furthermore, the situational analysis provided a suitable methodology for discerning how the research relation itself was characterized by irritations and uncertainty, joking practices, but also politicization and conflictual accusations. This showed how research situations during the pandemic were constituted by a specific relational reality, in which diverse forms of pandemic politics gained pertinence. [44]

I started this article by laying out how the global dimensions of the Covid-19 pandemic manifested in different spatial, social and political experiences. While the methodological and ethical repercussions of the pandemic on academia in general and field research in particular are increasingly discussed in the literature, the relational dynamics in research situations have not yet been comprehensively addressed. Against this background, I asked which relational dynamics evolve in the situation of conducting field research during a (global) pandemic and how these relate to different lived experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic. Building on a discussion of the pandemic's repercussions on field research, I summarized how my own lived experiences of the pandemic differed from the experiences of my interlocutors in Senegal. This was followed by a section on the theoretical and methodological implications of a relational research approach. By conceiving ethnographic research as inherently relational, I described how I attempted to employ a relational research practice, for which a comprehensive reflection of my research ethics and positionality is of crucial importance. In order to reflect upon and analyze the research situation evolving out of this relational approach to field research during the Covid-19 pandemic, I argued that a situational analysis is particularly fruitful. By conceiving of the pandemic and myself as the researcher as integral parts of the research situation, situational analysis provides a methodological basis for a reflexive analysis of the relational dynamics evolving in a research situation. [45]

The ensuing situational analysis built on a thick description of the research situation and its relevant elements, amongst which face masks, (global) pandemic politics and contesting vaccines in the research situation were addressed as specific examples. The relational dynamics between the elements were then analyzed and presented on the basis of two relational mappings combined into one map, in order to compare and reflect upon the relational embeddedness of myself and the university students in the research situation and the dynamics of the research relation. In this way, I showed how the Covid-19 pandemic did not only impact methodological and ethical decisions in the research process, but also how it entered the research situation itself and became relevant for its relational dynamics. On the basis of a situational analysis, I revealed how conducting field research during the Covid-19 pandemic involved relational dynamics of irritations, uncertainties, joking practices but also politicization and conflict dynamics on the basis of different lived experiences of the pandemic (politics). [46]

The relational dynamics of conducting field research during the Covid-19 pandemic underline that field research processes can never be considered independently of socio-political dynamics. Seemingly small decisions in the research situation are always deeply intertwined with global, national and local dimensions of (pandemic) politics, social inequalities and discourses. The relational research approach was particularly fruitful for becoming aware of how these dimensions are interwoven with different lived experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic. [47]

The establishment of long-term research relations and a strong reflexivity with regard to the methodical and ethical implications and socio-political dynamics within a research situation are hence crucial for better understanding research under exceptional circumstances, such as a pandemic. Building on this relational approach, I could better understand what the "crisis" of the pandemic exactly meant for the research participants and the research field (KHOO & KARA, 2023, p.3), and create a constant and careful risk assessment of my research (IRGIL et al., 2021, p.1512). Reflecting specifically on what it means to conduct field research during the Covid-19 pandemic also revealed how the dynamics of research relations address different lived experiences and political positionings. This reflection was facilitated by a situational analysis which shifted the research relation from an implicit situational factor to an explicit topic of discussion. A relational approach to research hence significantly improves our understanding of the Covid-19 pandemic as an allegedly global phenomenon in its complex and contradictory socio-political manifestations in research situations. Furthermore, by taking seriously the relevance of lived experiences in the Global South, these research reflections contribute to overcoming the analytic divide between domestic and international politics during the Covid-19 pandemic (PAPAGARYFALLOU, 2021, p.314). Finally, these reflections on the relational dynamics of conducting field research during the Covid-19 pandemic provide the possibility for informing future ethical considerations of conducting field research. [48]

Methodologically, I showed in this article that the increasingly popular theory/methods-package of situational analysis offers an important potential for reflexively analyzing research situations (OFFENBERGER et al., 2023, §19). Building on a situational analysis, I was able to reveal how the Covid-19 pandemic manifests in and shapes relational dynamics in research situations. Combining two relational maps in Figure 1 allowed me to illustrate the extent to which the relational embeddedness of myself and the university students in the research situation differed with regard to the pandemic-related experiences. The comparative use of the innovative analytical tool of relational maps (SCHWERTEL, 2023, §2) hence highlighted the complexity of relational dynamics in field research situations during the Covid-19 pandemic from the standpoint of different actors. This methodological potential is all the more important against the background of an allegedly global Covid-19 pandemic which is, however, experienced very differently spatially, socially and politically. I showed how these different lived experiences of the Covid-19 pandemic characterize the research situation and simultaneously relate to local manifestations as well as global politics of the pandemic. Consequently, the Covid-19 pandemic was always deeply interwoven with my research practice and positionality in the field. This sheds light on the difficulties of separating field research as a form of academic knowledge production from global inequalities, politics and post-colonial dependencies. These relational dynamics emerging during field research thus need to be interpreted against the background of conducting field research during an allegedly global pandemic with very different social and political manifestations locally. [49]

I would like to thank my colleagues at the Center for Conflict Studies at Marburg University for supporting me throughout my research process. I am particularly grateful for the fruitful and detailed feedback on this article by Eva FRONEBERG, Pia and Sophie FALSCHEBNER, Philipp LOTTHOLZ, Thorsten BONACKER, as well as by the anonymous reviewers. Most importantly, I would like to express my gratitude to the many great researchers and students at the UASZ, UCAD and UGB for all the support and trust during the research process. Finally, I would also like to thank the German Academic Exchange Service for financing my research with a short-term doctoral scholarship.

Interviews

I280121: Interview with a student at the UASZ

I090221: Interview with a student at the UASZ

I120621: Interview with a student at the UCAD

I2406212: Interview with a student at the UASZ

Interview notes

NI280121

Field diary notes

N201220

N261220

N020320

N040121

N070221

N020221

N210221

N280221

N180321

N260321

N290521

N3003212

1) In the following, references to empirical data will be abbreviated with an "I" for "interview," "NI" for notes d’interview [interview notes], and "N" for "note." These references are listed in the Appendix and numerically codified in order to guarantee anonymization. <back>

2) While being aware of the problematic of "fields" being predominantly conceived by an othered perspective on research in the Global South (ADJIRAKOR, AJAYI, DIMAN & YUAN, 2021, pp.vi-viii), I use the term in the broad sense of a social field (LORENZEN & ZIFONUN, 2012). Following this understanding, "doing fieldwork" is characterized by its embeddedness in different social research "fields," for which a variety of data collection methods can be used (IRGIL et al., 2021, p.1500). <back>

3) Some interesting examples of pandemic-related research reflections are for example provided by JUNG et al. (2021) or SCHAD-SPINDLER et al. (2023). <back>

4) This state of waithood even continued after the reopening of the university due to the uncertainty of whether an année blanche [blank year] should be created or whether the students should rapidly catch up the missed courses. <back>

5) One planned and one spontaneous group discussion took place at a later stage of the research process. However, these will not be part of this article's reflection. <back>

6) All translations from non-English texts are mine. <back>

7) This neologism is a merger of Macky SALL and Emmanuel MACRON. <back>

Adjirakor, Nikitta Dede; Ajayi, Oladapo Opeyemi; Diman, Hanza & Yuan, Mingqing (2021). Fieldwork experiences and practices in Africa. University of Bayreuth African Studies Working Papers, 27, https://epub.uni-bayreuth.de/id/eprint/5680/1/BIGSASworks%2810%29%20-%20Adjirakor%20et%20al-2021.pdf [Accessed: February 10, 2022].

Agostinis, Giovanni (2021). FORUM: COVID-19 and IR scholarship: One profession, many voices. International Studies Review, 23(2), 302-345.