Volume 9, No. 2, Art. 61 – May 2008

The Proof of the Pudding is in the Eating—but What was the Pudding in the First Place? A Proven Unconferencing Approach in Search of Its Theoretical Foundations

Patricia Wolf & Peter Troxler

Abstract: This article outlines how unconferencing contributes to the vision of a performative social science that aims at stimulating social change. The authors argue that conference participation is an integral part of research and has the potential to support social change by enabling learning processes. They then develop an unconferencing model from the theoretical reflection of different theories from social science which reveals that unconferences support individual and social learning processes through enabling knowledge transformation as well as through creating structural links between societal sub systems. Using the example of an elaborated unconferencing concept called UnBla (i.e., to remove the blah-blah) which has proven to work well, the authors explain how the theoretical principles of unconferencing are applied in reality and what the outcomes of unconferences can be.

Key words: conference, knowledge transformation, creation of structural links, perspective taking

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The Proof of the Pudding is in the Eating

3. What was the Pudding in the First Place?—Ingredients

3.1 General assumptions and aims behind the unBla concept

3.2 System level

3.3 Individual level

4. What was the Pudding In the First Place?—Method

4.1 unBla principles

4.2 A first attempt at a general model for unBla unconferencing

4.3 The unBla.07 conference

5. Summary and Outlook

In May 2007, Business Week published an article on unconferencing, a phenomenon that has been around, at least in some circles, for a while but has obviously reached business mainstream now. Unconferences are "(…) a hybrid of a teach-in and a jam session, with a little show-and-tell mixed in" (KIRSNER, 2007, n.p.). They promise participants "a lot of bang for the buck" (a participant)—or as David TAME puts it: "I don't see why I should pay hundreds of dollars for the privilege of being sold to" (KIRSNER, 2007, n.p.)—, although or rather just because they are completely unstructured, there is no detailed agenda set, no list of speakers. Instead, everyone who turns up co-authors the meeting—be it as a speaker, a reporter, a blogger, or a contributor in many other ways. Unconference formats prove to be hugely popular and successful as they seem to hit the zeitgeist. But could it be more than that? [1]

In this article we are trying to glimpse behind the hip façade of unconferencing. We are basing our work on a concrete instance of a specific unconference format. The format is called unBla (for "removing the blah-blah from meetings", see UNBLA TEAM, 2007a) and the conference was held in Central Switzerland (UNBLA TEAM, 2007b). First we briefly illustrate this example and its outcomes. Second, we take a step back to discuss a selection of theories and approaches from social science. These, we believe, are in fact some of the essential ingredients of unconferencing, explicitly or implicitly. Third, we establish the explicit links between these theories and the practical methods of unconferencing—or in our case of unBla. [2]

2. The Proof of the Pudding is in the Eating

The host of unBla.07 was Lucerne School of Business. They were, at the time, involved in a project to develop a regional innovation strategy for Central Switzerland, the so called RIS-project. Prof. Dr. Simone SCHWEIKERT, project coordinator, summarises their expectations and experiences:

"We aimed at generating an event where people from Central Switzerland can meet a truly international community and engage in both meaningful conversation and real work related to questions about regional innovation. (...) We had outcomes related to different dimensions of learning. One important thing we wanted to look at and experiment with was how to organise an innovative event with a very special regional and international group. (...) Now we know! unBla was a great opportunity to explore innovative methods to engage a heterogeneous group in meaningful conversation and at times even in generative dialogue. Content wise, we gained a lot of new insights during all sessions and we developed concrete ideas that will be used within the RIS project and beyond. We learned a lot from the experience of the travellers, but we also learned a lot about ourselves, about implicit unspoken assumptions we were carrying around. unBla helped us to make them explicit and to discuss them. (...) One of our participants told me, that he was excited about the speed in which the unBla team managed to build up trust in the group. I can only agree onto that. In my opinion, unBla has been an important step stone for the RIS project towards becoming an active and appreciated member of the European Research Area. (...) unBla is a prototype of events that provide the environment and atmosphere where people appreciate working together, storming each others brains and not only their own ones and exploring different perspectives. Participants at unBla events use diversity as a source for mutual learning and therefore for innovation" (quoted from UNBLA TEAM, 2007c, pp.79-80). [3]

Hosts of an unBla conference typically look for a way in which local people, the locals, can meet and interact with a truly international community, the travellers. The aim is to facilitate knowledge transformation among the participants, both for the benefit of the host organisation and of the individual participants themselves. unBla applies particular methods to specifically engage such a heterogeneous group in meaningful conversation and generative dialogue. Thus, an unBla conference becomes productive, instead of reproductive and participants not only listen, but also start talking to each other beyond small-talk: "Thanks for an awesome event—this gives the word conference a completely new meaning" (A. KIPOUROS, quoted from UNBLA TEAM, 2007c, p.81). [4]

Participants are excited about the speed in which unBla manages to build up trust in the group. unBla provides the environment and atmosphere where people appreciate working together, storming each others brains, not just their own, and exploring different perspectives:

"So what did it do for me (one word answer please!!!!!). Re-invigoration. With batteries recharged, motivation re-stimulated, I am back in London feeling intellectually and physically re-invigorated.

Did I learn anything? Well, it served to remind me of a very important ‘rule of engagement' when working in a multi-cultural environment. Meaningful dialogue, genuine cooperation and effective action only occur when we listen to what others have to SAY without our personal cultural values getting in the way of our understanding and/or acceptance of what THEY are saying. Communication on different wavelengths creates a ‘Babel Tower' (M.'s very concise expression). We really do need to be reminded of that from time to time, especially consultants like me" (J. DICK, quoted from UNBLA TEAM, 2007c, pp.82). [5]

unBla is centered around learning, primarily from the experience of locals and travellers, but it allows for learning about oneself and about ones own implicit unspoken assumptions. unBla uses diversity as a source for mutual learning and, therefore, for innovation. Hosts of unBla events gain new insights and concrete ideas that they are able to realise in their projects. [6]

Some examples from unBla.07 might illustrate how unBla achieves these results. To enable quality interaction, unBla pairs up participants in multiple constellations, randomly as well as purposefully, and uses different ways to document relevant connections between participants. For unBla.07, participants were asked to bring one small present or souvenir which would represent their home country. These presents were then collected and randomly distributed among locals and travellers respectively. These random connections lead to relevant dialogue over the participants' respective cultural backgrounds. In another assignment, participants had to match their professional profiles with similar profiles of other participants. These links were documented visually. For the introduction into the context of the conference topic, developing a regional innovation strategy for Central Switzerland, a storyteller told a local myth that illustrated both the traditional values and the innovation culture of the region. Further, to unleash the creative potential of the participants, we used non-textual approaches such as doodling or crafting. A last example—to link the three days of the conference, a video blogger captured some of a day's action and produced, overnight, an audiovisual summary that was played back the next morning as a trailer to start the day and to reconnect to the day before. [7]

In terms of methodological sources the unBla conference concept builds on methods from action learning (REVANS, 1998; WEINSTEIN, 1998), action research, weblogs and blogging, Delphi studies and includes elements of traditional journalism, event design and management. The main approach is to involve professionals from these methodological disciplines (such as researchers, bloggers or event designers) in the planning of an unBla event while the hosts of the event remain the owners of the content, i.e., the problems or questions to be worked on. [8]

3. What was the Pudding in the First Place?—Ingredients

From the above examples and testimonials, it is evident that unBla.07 was a highly valued experience for participants. In this section, we try to reflect on theories that support the concept and explain its success. In a first step, we make the general assumptions and aims explicit that are behind the concept of unBla. Thereafter, we are going to investigate basic problems concerning knowledge transformation amongst conference participants with which normal conference formats do not cope very well. [9]

3.1 General assumptions and aims behind the unBla concept

Performative Social Science is, in general, aiming at transformation in research: DENZIN (2003) envisions a social science that resembles a performance to become a sociopolitical act, or in other words: "(…) performance is transformative—it creates social change" (MARKULA, 2006, p.354). If social science aims at creating social change, then it should be innovative, and innovation is one major outcome of learning processes. Agreeing with DENZIN (2003), we argue here that conference participation is an integral part of research and has the potential to support social change by enabling learning processes. From our point of view, learning is what happens when the knowledge1) of an individual is transformed or changes (which, of course, needs to be stimulated by some sort of social interaction). Thus, conferencing concepts should aim at supporting knowledge transformation. This is the general aim of unBla conferences. [10]

For several years, different disciplines in social sciences which study collaboration processes have more or less independently developed the insight that there cannot be such a process as knowledge transfer that is linear, purposeful and predictable but that it is knowledge transformation that constitutes successful communication and interaction processes. TIETGENS (1988, p.5, in DEWE, 2005, p.370), for example, refers to the reciprocal aspiration of the partners of a communication process to integrate perspectives: "Attention needs to be drawn to the reciprocity of a transformation processes". DEWE (2005, p.368, our translation) points out that knowledge transformation is a process of relating knowledge and that such a process is necessary for ensuring the relevance of scientific knowledge for practitioners and vice versa. He highlights that one of the effects that cause the deficits in the so called knowledge transfer processes between scientists and practitioners results from the fact that the difference between declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge has not been taken into account. Such attempts are based on a feedback and discourse concept aiming at the communication of knowledge that has been constructed ex ante and validated according to criteria of scientific logic. However, these attempts have their origin outside practical discourse. In a discourse between scientists and practitioners, the validity of scientific knowledge for solving practical problems is not reviewed. To the contrary, scientists are rather convinced that they themselves are able to integrate scientific knowledge into the frame of reference of the addressees (i.e., the practitioners) in a communicative-persuading manner (DEWE, 2005, p.369). It is this process of knowledge transfer that we usually see not only in scientific, but also in practitioner conferences. For a long time, the scientific community has been stressing the importance of establishing a dialogue between the scientific community and other communities within society (see e.g., REBEL, 1989, p.141). However, when it comes to conferences, attempts to realise this dialogue do not go further than inviting policy makers and entrepreneurs to participate and present their problems and respective practical solutions in the format of keynote speeches or paper presentations. At the same conferences, scientific knowledge is presented next to or parallel to presentations from practitioners, mostly even in locally separated sessions. Scientists and practitioners do not work on the same problems; they just present their different perspectives without getting into real dialogue. Apart from short coffee breaks and conference dinners that do not allow deep discussions, there is no space foreseen for and dedicated to knowledge transformation between practitioners and scientists. Even worse, the same problem applies to scientists representing different schools of thought. [11]

The unBla concept tries to overcome this problem by stimulating the empowerment of a community—comprising practitioners and academics alike—to interact around a dedicated topic while providing a value proposition to all involved stakeholders equally, namely to gain practical knowledge (solutions) from interaction and to generate theoretical knowledge (concepts and findings) from the analysis of the interaction. Therefore, unBla uses methods and tools from Performative Social Science like performance, video, audio, graphic art, crafting, etc. It thereby aims at

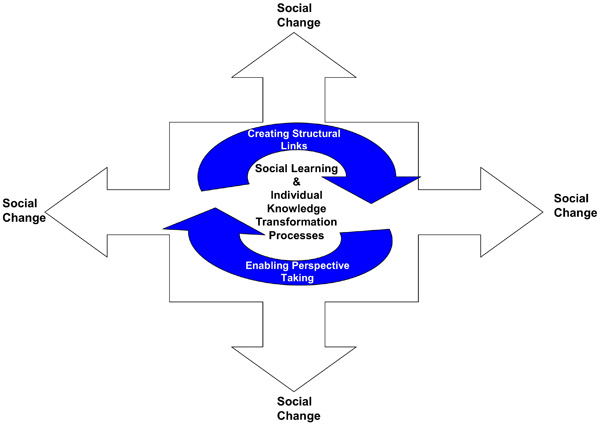

"(…) creating new spaces in which (…) meaningful dialogue with a wider audience is possible, and so feedback that is constructive and dialogical in its nature becomes feasible, and dissemination of social science data transforms into something not convivial, but also even playful" (JONES, 2006, p.67). [12]

unBla conferences trigger social change through supporting social learning processes that are based on and result in individual knowledge transformation. [13]

In order to understand the complexity of the issues unBla is addressing, a deeper look into the challenges to knowledge transformation at system and individual levels is needed. This has been pointed out by several theories that form the basis of Performative Social Science like Symbolic Interactionism (BLUMER, 1973) and Social Constructionism (GERGEN, 1985). At system level, a further theoretical perspective that is very close to Social Constructionism, but so far has not been used for explaining the challenges of Performative Social Science, will be added—the perspective of LUHMANN's Social System Theory (LUHMANN, 1984). In the next two sub sections we shall briefly outline these theories and their relevance to the unBla approach, first on a system level, then on an individual level. [14]

Connectivity (Anschlussfähigkeit) of communication is one of the major requirements for effective communication between different societal subsystems. According to LUHMANN's Social System Theory (LUHMANN, 1984), a society differentiates into several subsystems that act within their own communication and decision structures. This in general leads to problems in connectivity of communication between subsystems (e.g., science and economy). LUHMANN defines knowledge as a structure that supports the autopoiesis of communication—in other words, the emergence of communication from previous communication—through limiting the variety of possible connections for follow up communication (LUHMANN, 1996; p.42). The mechanisms a system builds for selecting information are called expectations. Expectations are applied to every communication. If expectations are not met, the system has two options: it can either keep the expectations and thus sustain existing knowledge (still acting based on its existing communication and decision structures) or it can give up the expectations and change existing knowledge (learn). Conferences can be seen as opportunities for communication that offer the possibility for building structural links between subsystems. Once these structural links are established, there is a realistic chance that existing expectations of the systems (like science and economy or different schools of thoughts) will be not met in communication and thus that system knowledge will be changed. This is how conferences can potentially contribute to social change. Normal conferences do usually not take the problem of connectivity into account. They do not work with methods that would result in establishing structural links; rather, they prevent them through creating separated spaces like specific sessions where communication happens within the same subsystem. Thereby, they enable connectivity within the same subsystem whose knowledge will then be sustained, but they do not support connectivity between different subsystems, thus they do not instil learning of the subsystems which could possibly result in societal change. [15]

LUHMANN's Social System Theory defines individuals only as communication addresses. However, systems are not able to learn without the help of individuals as they are not able to observe (BAECKER, 1998). It is individuals who observe their environment and then (potentially) translate their observations into communication relevant to the system. Thus, while LUHMANN's Social System Theory explains the general problem of connectivity between subsystems very well, it is not able to explain how learning processes among individuals can result in learning of systems. [16]

A theoretical perspective on society that sheds more light on this particular issue is the theory of Symbolic Interactionism. BLUMER (1973) outlines that groups and societies exist only in actions (not in communications between systems, as postulated by LUHMANN's Social System Theory). The Theory of Symbolic Interactionism also highlights the symbolic-interpretative character of human actions. According to BLUMER (1973, p.81), Symbolic Interactionism is based on three assumptions:

human beings behave in front of objects based on the meaning those objects have for them. Objects are everything that can be perceived: physical objects, other people, categories of classifications like friend or enemy, institutions, cultural values and norms, actions of other individuals, experienced or anticipated situations;

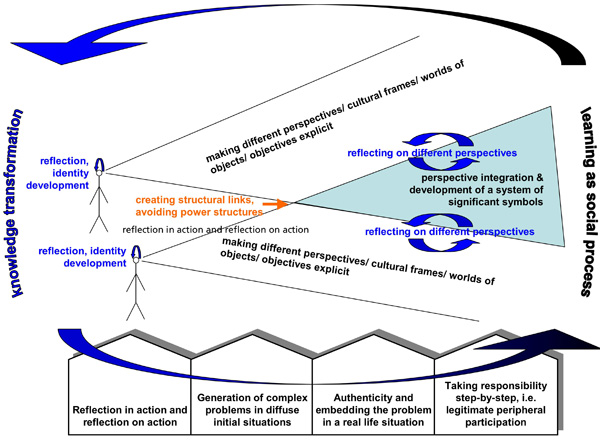

the meaning of these objects emerges or derives from social interaction with other human beings. Meanings (symbols) don't have their origin in an objective characteristic of an objective but neither in isolated subjective perceptions, which are said to structure perception and interpretation of the world of objectives. Rather, meanings emerge from the interaction process between several people; they are "(…) social products (…) that are created during and through the defined activities of people interacting" (BLUMER 1973, p.83, our translation); and

these meanings are applied and modified in an interpretative process by individuals when examining objects they come across. [17]

The meaning of objects is, therefore, socially created in a process of definition and interpretation, resulting from interactions between members of a subsystem. Individuals have, indeed, to deal with and to develop their actions towards this world of objectives. Thus, we can conclude that if we are to understand the actions of individuals, we have to get to know their worlds of objects. Normal conferences do not support the explication of the worlds of objects of individuals. Even if individuals are enabled to present the theoretical assumptions of their research, this does not tell much about how they perceive the world, it just gives a weak indication. As normal conferences provide only very short time frames for discussions, the opportunity for dialogue that would help to uncover the world of objects is limited. Participants are labelled by the theoretical background theory they present, and their world of objects remains hidden behind that label as no real dialogue is stimulated. [18]

Social Constructionism sees knowledge as constructed through social discourse (GERGEN, 1985). Pedagogic approaches and methods provided by the Learning Theory of Constructionism (for a summary see e.g., DUFFY & JONASSEN, 1992) further developed the theory of Symbolic Interactionism through considering learning as a social process and not as a behaviourist reproduction and combination of existing factual knowledge; the perceived reality can be seen as constructed by acts of subjective sense-making. Social reality is socially constructed. Consequently, there is no objective institution such as "the eye of God" outside human perception that allows classifying insights, ideas or knowledge as true or false (BAUMGARTNER & PAYR, 1997), and external reality becomes important for a single researcher by gaining his/her perception and bearing on the own life. Normal conferences do not stimulate explicit reflection on that issue amongst the participants. Sessions are defined rather by defending the own position than by integrating different perspectives and elaborating what can be learned from them. As a result, different points of view are shortly presented, but similarities and differences are not reflected; integration of views does not happen. [19]

Situation is another important element that Symbolic Interactionism focuses on. The theory explains that acts of interpretation happen in the frame of specific situations. Social situations are, on the one hand, objectively given (time, place, number of people etc.), and, on the other hand, their reality depends from subjective interpretation. In other words, what individuals expect from a situation and what they anticipate to be or not to be happening, is not the same for different individuals with different objectives. "'Situation' is something ambiguous: structured by common, but also by discrepant or 'subliminal' meanings" (ABELS & LINK, 1991, p.7). The situation of normal conferences is set according to principles that are familiar to most of the participants—they take place at conference hotels, open with a keynote, thereafter several parallel sessions take place, networking happens during lunches and dinners etc. On the one hand, this creates a certainty amongst the participants of what will happen. On the other hand, it is assumed that all participants will be happy with that situation, in that it does meet not only the expectations, but also the objectives, of each and every participant. Anybody who has ever been to a conference where ninety percent of participants disappear after their own presentation and only reappear for the conference dinner, knows that this assumption can hardly be true. [20]

Power in discourses is a further element that potentially limits the learning of individuals (and thus systemic learning) in social systems. HABERMAS (1968) outlines in his philosophical theory of communicative actions that discourse is a process of negotiating individual claims. In the FOUCAULTian conception, discourse is seen as a complex network of relationships between texts, ideas, individuals and institution, with each node impacting, to varying degrees, on other nodes, and on the dynamics of the discourse as a whole. FOUCAULT (1972, 1980) emphasised that members of a discourse community have a set of "discursive rules" (connections) that shape the form that a valid truth statement can take and, more fundamentally, they dictate what can be said in the context of that discourse. FOUCAULT constructs the relationship between knowledge and power as central to his conceptual framework: "Power and knowledge directly imply one another; that there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge, nor any knowledge that does not presuppose and constitute at the same time power relations" (FOUCAULT, 1972, p.27). Power seems thus to be a phenomenon that on the one hand structures communication (see e.g., LUHMANNs' decision structures in organisations, LUHMANN, 2000), on the other hand, it limits what statements can be made in a certain community. At usual conferences, we often see that the power of (pre-)existing communities that attend the conference is used to deconstruct other participants' arguments and make them to stay quiet. In line with that, HABERMAS (1968) argues that only communication that is free of distortion by power and hierarchies is rational and enables real insights, right norms, and authentic feelings. Here again, normal conferences do not aim at breaking away from existing power structures in discourses but rather support them by turning sessions into defence exercises of research ideas and results rather than by supporting power free discourse. [21]

As the constitution of meaning of objectives happens in social interaction, as explained above, and as meaning is derived by individuals from this interaction, the use of meaning by individuals is more than just an automatic application and actualisation of existing symbols; individuals enter a process of conversation with themselves during the interaction with others. Interpretation thus is a "(…) formative process, during which meanings are applied and changed in order to steer and build up actions" (BLUMER, 1973, p.84, our translation). As meanings of objects are not stable, but formed and transformed in a continuous social process of interpretation, this is where we can see knowledge transformation happen at an individual level. In order to understand how this process works, we need to go a bit deeper into the theory of Symbolic Interactionism and review the basic concepts of identity development and role taking. [22]

Identity results from a process of internalisation of social norms and roles. During this process, an individual does not relate to concrete psychological parents—as it does in early childhood—but to attitudes, expectations and values of a number of significant others. "This implies the gradual extension and generalisation of subjectively valid norms as well as their revision" (ABELS, 1999, p.34, our translation). MEAD (1968) calls the sum of those abstractions that represent general valid attitudes, values and expectations "the generalised other", the representative of society inside the individual. GOFFMAN (1977) refers to the generalised other as "cultural frame". Following his argument, experiences an individual makes are steered by "frames", specific perspectives. "Perspectives" are nothing more than "(…) the organised structure of experiences of individuals" (GOFFMAN, 1977, p.19, our translation). Perspectives create the framework for the definition of a situation. In every society there is a certain inventory of "framing conversations" in terms of commonly used interpretation schemata that help the individual to understand specific situations "in the correct sense" (ABELS & LINK, 1991, p.10, our translation). When MEAD (1968) states in his Sociology of Knowledge that the perspective of an individual is limited by his or her knowledge, this does not mean that this individual perspective is something that is not related to those of others. BLUMER (1973) outlines that each individual develops his or her own identity, and that it is this identity that enables a person to react to other individuals not just on a non-symbolic level (as animals do). MEAD (1968) explains that an individual needs to see himself/herself from the outside in order to develop a self-object. As other objects, the self-object emerges from the process of social interaction. This is only possible within a process of perspective or role taking: The individual puts himself/herself in the position of others and acts in relation to himself/herself. Identity thus always emerges from this process of perspective or role taking. [23]

Perspective or role taking is a central process not only to the development of identity, but also to communication and interaction processes between individuals. Here, perspective taking is achieved with the help of significant symbols. Significant symbols are symbolic gestures that evoke the same association of a meaning for the interacting individuals (MEAD, 1968, p.188). As these symbols evoke not random but very specific reactions, the latter can be anticipated. Social interaction is thus characterised by reciprocal efforts of actors to reconstruct and anticipate the subjective meaning of acts of others. The process of perception and reaction comprises continuous interpretation by both partners. It is this constant process of investigating testing roles of both others and oneself that influences the structure of the interaction process. This also means that roles and meanings can be defined only for provisionally as they are constantly re-interpreted (ABELS & LINK, 1991, p.3). [24]

We arrive at the heart of the problem that individuals face in situations where they meet others who they do not know: for perspective/role taking to be successful, significant symbols need to be compatible between the two parties. This is typically not given when people from different cultures or countries meet at a conference. To make matters worse, language plays an important role in this process:

"The availability of a system of significant symbols in terms of shared linguistic terms and patterns for interpretation enables individuals to understand the expectations of others faster and clearer. Also, the own validations, claims and wishes can be formulated more unambiguously" (ABELS, 1999, p.27). [25]

Empirical studies by KRAUSS and FUSSELL (1991) uncovered that "(…) messages addressed to a friend are communicated more effectively to that friend than to some other person" (p.20). Normal conferences do not pay much attention to these problems in the process of perspective taking. Instead they assume that communication processes are linear, i.e., that everything that is said would have the same meaning for all participants that hear it. Moreover, they ignore the problem of different languages of the participants. [26]

GOFFMAN (1969) explains that when an individual meets others, these others try to gather information about him (character, aims, status, values etc.) or to apply the information they already have. If they know the other, they assume that personal characteristics are stable; and based onto these assumption they are able to anticipate his further reactions. If they do not know the other, they try to gain information from his/her appearance and allocate the individual to a category of persons, a type. In line with that, empirical studies by KRAUSS and FUSSELL prove "(…) that speakers attempt to adapt their messages to the background knowledge and perspectives of their addressees and that these efforts have consequences for the clarity of the messages" (1991, p.9). At normal conferences, people classify others based on first level generalisations, categorising them based on their first appearance. This again furthers communication and even power structures that are based on very limited and superficial information such as the same age or the same style of dressing etc. and possibly prevents communication between people from very different subsystems. [27]

ABELS and LINK outline that "(…) common interpretation patterns that are shared between individuals constitute a "we-feeling" that generates the certainty of a common social reality" (1991, p.12, our translation). Normal conferences assume that, as all participants are interested in the same topic, this we-feeling exists. An interest in the same topic, however, doesn't indicate similar or even common interpretation patterns. These patterns need to be developed through meaningful dialogues among the participants; they require creating a common world of objects and a common language on the topic. Or, in other words, knowledge transformation would pave the way for the development of common interpretation patterns amongst conference participants. [28]

In the next section, we explain how unBla addresses these problems of knowledge transformation by applying methods and instruments from Performative Social Science, and we make an attempt at a first generic theoretical framework for unconferencing. Using the example of unBla.07 we give evidence on how the unBla concept could be put into practice. [29]

4. What was the Pudding In the First Place?—Method

From the theoretical discussion above it became obvious that conventional conference formats are not able (or only to a very limited extent) to contribute to the vision of a social science that stimulates social change. Social change starts with knowledge transformation at an individual level: knowledge transformation is the result of learning processes, and conferences should provide environments and occasions where learning actually can happen. Conference participants themselves hold these expectations. When talking about reasons for going to conferences, participants usually underline their aim to learn; beyond presenting and disseminating their own research findings, they want to receive feedback, gather new ideas and share lessons learned and best practices (RULEY, 2006; WEST, 2004). However, normal conferencing formats usually do not satisfy these needs. JONES (2006) expresses the feeling that Performative Social Science could provide methods and tools to overcome this problem:

"Exploring the possibilities of a Performative Social Science, for me, grew directly out of dissatisfaction with limitations in publication and presentation of my own biographic narrative data. For instance, my reciting papers or, worse, reading text from PowerPoint presentations directly to them (audiences who were certainly capable of reading slides for themselves) contributed to my self-inflicted discontent" (p.67). [30]

First attempts to unconferencing concepts can be seen in Robert JUNGK's method of "Future Workshops" he developed in the 1960s (JUNGK & MÜLLERT, 1981; TROXLER & KUHNT, 2007) as an answer to developments in a predominantly techno-scientific society. The aim of Future Workshops is "(…) giving the people concerned the possibility to meet, to unleash their hidden potentials and to mentally prepare for social change" (Robert JUNGK in an interview with Wolfgang WEIHRAUCH, 2002, n.p., our translation). [31]

Later developments include the Open Space Technology. Open Space Technology was created in the mid-1980s by the organisational consultant Harrison OWEN (1997) when he discovered that people attending his conferences loved the coffee breaks better than the formal presentations and plenary sessions. Combining that insight with his experience of life in an African village, OWEN (1997) created a totally new form of conferencing. Open Space conferences have no keynote speakers, no pre-announced schedules of workshops, no panel discussions, no organisational booths. Instead, sitting in a large circle, participants learn in the first hour how they are going to create their own conference. Almost before they realise it, they become each other's teachers and leaders. [32]

Starting from there, the unBla unconferencing concept builds on the idea of Open Space Technology and developed it further. Concept wise, unBla also wishes to empower participants of a conference to take over ownership on the conference topic. However, the topic is given and unBla supports the process of perspective taking and build up of structural links through further moderation elements. Thus, open space sessions are elements of unBla conferences, but they are not seen as the only means of facilitating dialogue among participants. Although very good in supporting perspective taking, one of the major problems of open space technology is that it is not as effective as unBla conferences in dealing with systemic processes: it does not necessarily break away existing power structures or avoid the build up of new ones. Single participants are in fact provided with the opportunity to speak up in open space sessions, but power and hierarchy might force them to step back again and stay silent. The unBla conference concept takes a serious effort to make individual perspectives explicit through individual exercises like crafting and drawing, and enables participants more effectively to bring in their point of view. [33]

The aim of the unBla concept (and of other unconferencing approaches) is to make use of Performative Social Science methods and tools for creating social change. In other words, the idea is to exploit the potential that conferences provide as communication environments instead of ignoring that potential systematically. So, conferences need to stimulate social learning processes (resulting in individual knowledge transformation). From the theoretical discussion above it follows that learning as a social change process using the means of Performative Social Science can only be successful if two basic sub processes are supported:

To enable the creation of structural links between societal subsystems (structural condition).

To support and facilitate perspective taking (socio-cognitive condition). [34]

Figure 1 illustrates this:

Figure 1: Learning and knowledge transformation processes [35]

The unBla concept has been designed to support exactly these two sub processes and thereby to stimulate social learning and individual knowledge transformation processes that are likely to result in social change. To this end, methods from Performative Social Science are used "(…) which are counter-intuitive, unexpected and polyvocal" (JONES, 2006, p.68). Regarding their content, unBla conferences are designed around the topic of the conference and the objectives of the conference hosts. Methodically, however, they build on general principles to support the creation of structural links and to enable perspective taking. In the next subsection, we outline these principles. Thereafter, we suggest a tentative general model for unconferencing. Finally, we demonstrate how these principles have been put into practice in the above example, the unBla.07 conference on regional innovation. [36]

unBla supports the creation of structural links between societal subsystems through fostering communication between participants from these different subsystems—be it from academia and industry, be it from different countries and/or cultures. unBla offers unusual communication channels and facilitates the use of these channels by the participants. Once these structural links are created, they will lead to a stronger connectivity of communications between the subsystems and enforce systemic learning. [37]

With the help of a networking exercise at the beginning of the conference and other open facilitation methods, unBla aims to enable constructive discourse among participants in a power free environment. By continuously changing communication partners and teams, unBla tries to avoid classifications of others based on first level generalisations (decisions who to talk to based on the first appearance of the other) and to stay away of establishing power structures. Additionally, existing power structures are broken up by assigning communication partners at random. This helps the process of getting to know each other and stimulates negotiating and defining shared significant symbols. [38]

unBla supports perspective taking by stimulating the processes of identity development, self reflection and social interaction at the same time. During unBla conferences a lot of time is dedicated to identifying the world of objects of individuals by trying to make the meanings of objectives explicit. This potentially enables learning in terms of the conversion of the meanings of objects. unBla doesn't assume that a "we-feeling" already exists amongst participants. Rather, unBla creates situations for interaction and communication so the participants have to make their perspectives on the conference topic explicit, and they have to develop shared significant symbols. The latter process is not only triggered by "verbal" discussion (communication) but also through drawing, crafting, telling stories etc. At the same time, unBla also helps the participants to experience that there are already commonly shared interpretation patterns and meanings concerning a certain area of topics. [39]

The unBla concept aims to provide the participants with the perfect situation for perspective taking. It works, therefore, with ambiguity. It does not presume that there is a consensus among participants on what should be reached by the conference, but it tries to make explicit different expectations. Furthermore, the conference situation itself is ambiguous: participants don't know what they have to expect in detail, yet they know that the conference program will not follow the usual conference formats, be it in terms of content or methods. This expectation allows them to actively engage in an uncertain situation, to feel certain in uncertainty. In addition, by using unconventional facilitation methods, unBla creates a situation where individuals are likely to go off-beat, and this holds the opportunity of alienation. Alienation draws the attention of individuals on their usual techniques of self-confirmation and thereby enables reflection. All situational components are based on the architectural principles for constructivist learning environments. [40]

The principles unBla conferences are based on are reflection in action and reflection on action, generation of complex problems in diffuse initial situations, authenticity and embedding the problem in a real life situation, and enabling to take responsibility step-by-step, i.e., legitimate peripheral participation (see also e.g. BAUMGARTNER, LASKE & WELTE, 2000).

Articulation and reflection (MANDL, GRUBER & RENKL, 1997) focus on reflection in action and on reflection on action. The major difference to abstract theoretical knowledge is the fact that the knowledge extracted in the process of reflection and articulation remains on the one hand in the context of the concrete situation, while on the other hand it represents or creates general knowledge that can be adapted and shared.

Generation of complex problems in diffuse initial situations (SCHÖN, 1987) is expected to produce an emphatic relation of the participants to the problem or question discussed because it requires participation in the detailed definition of the problem.

Authenticity and embedding the problem in a real life situation (CHAIKLIN & LAVE, 1998) supports the recognition of the problem or question discussed as important for the participants or their organisation.

Taking responsibility step-by-step, i.e., legitimate peripheral participation (LAVE & WENGER, 1991) allows the definition of a self dependent role within a community of practice. Consequently this leads to learning by reflection, which is not achievable if people do not take responsibility. [41]

4.2 A first attempt at a general model for unBla unconferencing

unBla unconferencing needs to support the challenges of role taking on an individual level, such as self reflection and identity development and making the objectives, perspectives, cultural frames and worlds of individual participants explicit. This also includes keeping the differences in participants' worlds of objects present during the whole conference, reflecting on them, and integrating different points of view. [42]

On a system level, unconferencing sensu unBla aims to create structural links between subsystems, to avoid the emergence or dominance of power in discourses, to prevent first level generalisations in perceptions of people and to eliminate of (pre-)existing power structures. [43]

Eventually, unconferencing à la unBla will have to support, on an individual level again, the development of a system of shared significant symbols and common interpretation patterns, which additionally requires overcoming language problems as well. [44]

Achieving these requirements by applying the four principles of reflection in action and reflection on action, generation of complex problems in diffuse initial situations, authenticity and embedding of the problem into a real life situation, and enabling to take responsibility step-by-step, i.e., authorised peripheral participation, unBla enables learning as a social process which in turn leads to or is the basis of knowledge transformation and vice versa. Figure 2 visualises this general model for unconferencing.

Figure 2: unBla conferencing model [45]

We will demonstrate below how unBla.07 has been designed around this model. [46]

In this section, we use the unBla.07 conference as a showcase to explain in detail how the unBla principles could be put into practice. A brief summary should familiarise readers with the outline of the conference. [47]

After the usual arrival of the delegates, check-in, and registration delegates were treated first to a half-hour relaxation session, before launching into opening, networking part of the conference. Delegates brought souvenirs from their home country, which were anonymously distributed as presents to other delegates—the travellers' presents to the locals and vice-versa. Thus a first set of pairs of delegates emerged. In pairs they had to interview each other on their professional background and draw up a quick profile of their partners. The relationships between all the profiles were then visually constructed on the floor. The next sequence included a walk through picturesque Lucerne in larger groups, trying to avoid the usual tourist traps. The walks all ended at one place where a storyteller told a modern variation of an ancient saga from Central Switzerland, illustrating both local customs and the local way of dealing with innovation. To wrap-up the work, delegates had to summarise their impressions both in an icon depicting one ingredient of an innovative region and a verbal statement of what they learnt that day. After a reception at the city hall—which included, again, stories from innovative regions, this time presented by travellers—the delegates were encouraged to join some of the locals at their favourite restaurants to dine and discuss local issues of relevance to the conference. [48]

The next day's session was held just outside Lucerne at a furniture design studio and factory. After a video clip with the statements from the first evening, the day started with a non-verbal task: delegates had to model an innovative region with cardboard and other crafting material. Participants then used these models as a basis to develop a story of what successful regional innovation would comprise, based some five models clustered randomly. Just before lunch the syntheses of these stories were told to the plenary. After lunch, an open-space-like session addressed particular issues of regional innovation. A tour to the furniture studio concluded the working sessions, and participants had to summarise the whole day in one word. After dinner, on the coach back into town some of the participants staged a knowledge exploration tour. [49]

The last day was dedicated to innovation processes. After a video clip with the "one word" statements, delegates were divided into four groups. Two local companies volunteered to present their innovation processes, just to have them destroyed—the delegates were asked to come up with as many possible irritations, disturbances and disruptions of these processes. These interventions were then used to identify potential further improvements of the companies' innovative potential. The other two groups worked on their own recent experiences of "unexpected" events in innovation settings analysing the potential reasons using the 5-whys-technique. All teams thus dealt with the issue of un-planning innovation. The conference closed at lunchtime, but participants could attend a proposal-planning meeting for the upcoming calls from the seventh European funding programme for research and technological development. [50]

Table 1 describes Performative Social Science methods and tools used at the unBla.07 conference in response to challenges posed by the requirement to support perspective taking processes:

|

Support self reflection / identity development |

|

Registration: Participants had to relate the topic of the conference to their professional biography. Individual exercises stimulating self reflection, e.g., crafting of regions,

|

|

Make different objectives of participants explicit |

|

Registration: As part of the registration process, participants had to state how they would like to contribute to the conference. Initiatives proposed by participants were integrated into the conference programme, e.g., presentations of stories from innovative regions in the city hall, complexity workshop, project poster exhibition, knowledge exploration tour in the bus etc. For customising the event, the unBla team together with the host organisation had thorough discussions at a conference preparation workshop. Online forum for conference preparation: Participants had the opportunity to participate in a pre event discussion forum where they could discuss "hot" issues concerning the conference topic with other prospective participants. |

|

Make different perspectives, cultural frames and worlds of objects explicit |

|

Perspectives of locals were made explicit at the first day through a storyteller a visit to city (locals had to guide travellers to their favourite non- tourist places), and a reception by local government at Lucerne city hall. Topical dinners on the first evening served as a means to start discussions on hot local topics: Locals did not only propose their favourite restaurant but also a topic for discussion over dinner, and they invited travellers to join them. Participants were asked to draw icons that would represent ingredients and spices of regional innovation and to craft a region that would be able to continuously renew itself. During the networking session on the first day, participants had to interview a partner and find out about her/his professional background. Deconstruction exercise: CEOs of innovative companies from Central Switzerland had to describe their innovation process while participants had the task to identify potential occasions and means to disrupt this process.

In the reflection exercise at the end of each day participants had to make explicit what they had learnt that day.

A visit to an innovative (furniture) company showed how innovation happens in Central Switzerland.

|

|

Keep differences in participants' worlds of objects present during the whole conference, reflect on them |

|

The icons representing ingredients and spices of regional innovation and the crafted models of innovative regions were kept in the room. The network visualising the different backgrounds of the participants was kept in the room. During the deconstruction exercise, selected participants were playing "devils advocates": They were systematically questioning the ideas and conclusions groups came up with, thereby making explicit the assumptions that supported these conclusions. |

|

Support integration of different points of view, support the development of a system of significant symbols & common interpretation patterns (incl. dealing with language problems) |

|

After individually crafting models of innovative regions, participants had to search for common patterns between their own and their neighbours' models and to develop a common story linking these models.

One group developed a common influence map indicating and visualising the group's understanding of what were the biggest influences on regional development and how they were related to each other. Cross-regional consulting and mentoring:

Deconstruction exercise: CEOs of innovative companies and conference participants developed a common understanding and shared ideas on how potential disruptions of the companies' innovation processes could help the company to make the most out of the company's innovative potential. Drawing, crafting and interaction helped to overcome language problems.

Some of the crafted models of innovative regions were printed on postcards and sent out to the participants. They are now symbols of innovative regions for the whole group. |

Table 1: Methods and tools used at the unBla.07 conference for supporting perspective taking processes [51]

Table 2 presents Performative Social Science methods and tools used at the unBla.07 conference in response to challenges posed by the requirement to support systemic processes:

|

Create structural links between subsystems |

|

Participants had been pre selected: 50% came from academia, 50% from industry or consultancy. In addition, 50% of the participants were Swiss (locals), 50% foreigners (travellers). The visual network, an outcome of the networking session, did serve as a continuous visualisation of thematic and professional links between participants.

The whole conference format did stimulate expert discussions between members of different social subsystems and engaged participants into meaningful dialogue instead of defending slide presentations. The afternoon after the conference was dedicated to an FP7 proposal workshop (restricted to conference participants): The objective was that participants from academia and industry would define common topics and issues to work on in applied research projects. |

|

Avoid power in discourses |

|

Alteration of behaviour linked with power: A whistle was used for signalling the start of sessions and driving participants into sessions. The conference started with a 30 minutes relaxation session where participants were allowed (and gently coerced) to make themselves comfortable and to relax).

Signs of power were avoided as far as possible, e.g. name badges indicated just names but no affiliations, titles etc. Communication of conference concept: |

|

Prevent first level generalisations in perceptions of people and break away (pre-)existing power structures |

|

Continuous random selection of communication partners: In the networking session, participants selected their partners randomly by picking up presents that were distributed anonymously, so participants had to find out who their present came from.

In the crafting session, the physical proximity of crafted models was used to form groups. In the deconstruction sessions the organisers had groups prearranged to be as diverse as possible. For the city visit participants standing in the same queue formed a group. |

Table 2: Methods and tools used at the unBla.07 conference for supporting systemic processes. [52]

In this paper we discussed the foundations and practice of unBla, an unconferencing approach, in the light of Performative Social Science. The paper addressed unconferencing on three levels. First, on a theoretical level, we investigated the foundations of unBla in social science, thus establishing its foundations. Second, we described the methods used in this specific form of unconferencing, explaining how unBla changes the way we address the dissemination of research results. Third, using the example of unBla.07, we illustrated how these theories and methods have actually been put into practice. [53]

unBla and other unconferencing approaches in general are performative approaches to research dissemination that, as valid alternatives to ordinary PowerPoint conference presentations, actually turn dissemination into a co-productive or co-creative process with the audience. They not only release the communicative powers of research, but they also promise to achieve knowledge transformation for both parties—"the researchers" and "the audience", the academics and the practitioners. [54]

From the theoretical discussion, as well as from linking theoretical insights to the manifestations of the unBla.07 conference in Central Switzerland, it has been possible to develop an unconferencing model drawing on both theoretical insights and practical experience. From this, it is now possible to explain the advantage of unconferencing when it comes to knowledge transformation and learning as social process. We hope that in doing so this paper might become a contribution to the foundational references for the performative turn in social science. [55]

One question still remains open: Did unBla.07 stimulate social change? To be brief: It did. unBla.07 tried to reject predetermined views; rather than giving "the right answer" unBla.07 encouraged participants to continually look for innovative ways to try new structures, ask new questions, develop new views, and to adopt a common perspective. While indicators for social changes are hard to find—as social change would not happen in the conference itself but afterwards—a number of short statements by participants might explain how unBla.07 did trigger change and has the potential to induce social change.

New contacts: unBla did trigger new contacts that resulted in relationships that are sustainable. Participants still communicate with each other, locals visit travellers, they recommend each other for jobs etc. The conference even created new job opportunities for some of the participants.

New initiatives: unBla did stimulate further common initiatives amongst the participants. At least three initiatives for applied research projects resulted directly from the unBla.07 conference, foreigners travel regularly to Central Switzerland for seminars and lectures at Lucerne School of business, and there is even an initiative of a Swiss company to create an idea hotel together with people experienced in establishing future centres.

Methods: unBla did change the ideas of people on how learning can be supported in conferences. Participants still refer to unBla.07 as landmark in their conference experience. Some actively engage in integrating methods and tools from Performative Social Science into other events.

Application: Participants did get many ideas on methodologies and on processes they might want to try out in their own environments. One of the CEOs of the companies participating in the deconstruction sessions did put it like this:

"It is important to have people looking at the innovation process. I know now from your feedback that we are on the right track but could do better in some areas, and you told me how to proceed. It is great to know some alternatives. I liked the idea to send people out and give them more freedom to develop ideas—you confirmed that this is a good idea. We already had something similar in mind, but were not sure. I will go back and try the method we have experienced today internally with our people in the next meeting" (Dr. M. PEETZ quoted from UNBLA TEAM. 2007c, p.57)

So, in conclusion, we find that the theories underpinning Performative Social Science as well as its methods, tools and instruments seem to be appropriate for unconferencing. Moreover, those new, performative-based dissemination techniques help to reach wider audiences more sustainably. This is good news, for the researchers whose studies reach a wider audience more easily and for that larger audience itself who gets easier access to the findings and becomes more directly involved in exploiting the results. [56]

We would like to thank: Dr. Abdul Samad (Sami) KAZI who helped to develop the concept presented above; the host organisation of unBla.07: the Institute of Management and Regional Economics at Lucerne School of Business, especially Prof. Dr. Simone SCHWEIKERT; all UnBla.07 participants for that we are allowed to use the video material from the conference; Roger LÈVY for recording and editing the videos at and for unBla.07.

1) Knowledge as we understand it here is a structure or a repertoire of strategies for dealing with information that has been built from data by systems or individuals. Knowledge enables and enforces handling information selectively (WOLF, 2003, p.46). <back>

Abels, Heinz (1999). Interaktion und Identität im Medium symbolischer Kommunikation. G. H. Mead. Hagen: Fern Universität in Hagen.

Abels, Heinz & Link, Ulrich (1991). Interaktion und Identität im Medium symbolischer Interaktion. G. H. Mead. Kurseinheit 2: Symbolischer Interaktionismus I. Hagen: Fern Universität in Hagen.

Baecker, Dirk (1998). Zum Problem des Wissens in Organisationen. Zeitschrift OrganisationsEntwicklung, 3, 5-21.

Baumgartner, Peter & Payr, Sabine (1997). Erfinden lernen. In Albert Müller, Karl Müller & Friedrich Stadler (Eds.), Konstruktivismus und Kognitionswissenschaft. Kulturelle Wurzeln und Ergebnisse. Zu Ehren Heinz von Foersters (pp.89-106). Wien: Springer Verlag.

Baumgartner, Peter; Laske, Stephan & Welte, Heike (2000). Handlungsstrategien von LehrerInnen—ein heuristisches Modell. In von Christoph Metzger, Hans Seitz & Franz Eberle (Eds.), Impulse für die Wirtschaftspädagogik. Festschrift zum 65. Geburtstag von Prof. Dr. Rolf Dubs (pp.247-266). St. Gallen: Verlag des schweizerischen kaufmännischen Verbandes (SKV).

Blumer, Herbert (1973). Der methodologische Standort des symbolischen Interaktionismus. In Arbeitsgruppe Bielefelder Soziologen (Eds.), Alltagswissen, Interaktion und gesellschaftliche Wirklichkeit. Vol. 1 (pp.80-101). Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt.

Chaiklin, Seth & Lave, Jean (1998). Understanding practice: Perspectives on activity and context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Denzin, Norman K. (2003). Performance ethnography: Critical pedagogy and the politics of culture. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Dewe, Bernd (2005). Von der Wissenstransferforschung zur Wissenstransformation: Vermittlungsprozesse—Bedeutungsänderungen. In Gerd Antos & Sigurd Wichter (Eds.), Wissenstransfer durch Sprache als gesellschaftliches Problem (pp.365-379). Frankfurt/Main: Peter Lang Verlag.

Duffy, Thomas & Jonassen, David (1992). Constructivism and the technology of instruction: A conversation. Hillsdale NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Foucault, Michel (1972). The archeology of knowledge. London: Tavistock.

Foucault, Michel (1980). Knowledge/power: Selected interviews and other writings 1972-1977. London: Harvester Press.

Gergen, Kenneth (1985). The social constructivist movement in modern psychology. American Psychologist, 40, 266-275.

Goffman, Erving (1969). Wir alle spielen Theater. Die Selbstdarstellung im Alltag. München: Piper.

Goffman, Erving (1977/1974). Rahmen-Analyse: ein Versuch über die Organisation von Alltagserfahrungen. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Habermas, Jürgen (1968). Technik und Wissenschaft als "Ideologie". Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Jones, Kip (2006). A biographic researcher in pursuit of an aesthetic: The use of arts-based (re)presentations in "performative" dissemination of life stories. Qualitative Sociology Review, 2(1), 66-85.

Jungk, Robert & Müllert, Norbert (1981). Zukunftswerkstätten. Wege zur Wiederbelebung der Demokratie. Hamburg: Hoffmann & Campe.

Kirsner, Scott (2007). Take your power point and … Business Week, May 14, 2007, http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/07_20/b4034080.htm?chan=top+news_top+news+index_technology [Date of access: May 02, 2008].

Krauss, Robert & Fussell, Susan (1991). Perspective taking in communication: Representations of others' knowledge in reference. Social Cognition, 9, 2-24.

Lave, Jean & Wenger, Etienne (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Luhmann, Niklas (1984). Soziale Systeme. Grundriß einer allgemeinen Theorie. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Luhmann, Niklas (1996). Wissenschaft als soziales System. Hagen: FernUniversität in Hagen.

Luhmann, Niklas (2000). Organisation und Entscheidung. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Mandl, Heinz; Gruber, Hans & Renkl, Alexander (1997). Situiertes Lernen in multimedialen Lernumgebungen. In Ludwig Issing & Paul Klimsa (Eds.), Information und Lernen mit Multimedia (2nd edition, pp.167-178). Weinheim: Psychologie-Verlags-Union.

Markula, Pirkko (2006). Body-movement-change. Dance as performative qualitative research. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 30(4), 353-363.

Mead, George Herbert (1968). Geist, Identität und Gesellschaft. Aus der Sicht des Sozialbehaviorismus. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Owen, Harris (1997). Open space technology: A user's guide. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Rebel, Karlheinz (1989). Wissenschaftstransfer in der Weiterbildung. Der Beitrag der Wissenssoziologie. Weinheim: Beltz-Verlag.

Revans, Reginald (1998). ABC of action learning: Empowering managers to act und to learn from action. London: Lemos & Crane.

Ruley, Jeff (2006). 3 reasons to attend a conference, http://jeffruley.typepad.com/online_marketing/2006/08/3_reasons_to_at.html [Date of access: May 02, 2007].

Schön, Donald Alan (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. Towards a new design for teaching and learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Troxler, Peter & Kuhnt, Beate (2007). Future workshops. The unthinkable and how to make it happen. In Abdul S. Kazi, Liza Wohlfart & Particia Wolf (Eds.), Hands-on knowledge co-creation and sharing: Practical methods & techniques (pp.483-495). Helsinki: VTT.

unBla Team (2007a). UnBla.org, http://www.unbla.org/ [Date of access: May 02, 2008].

unBla Team (2007b). UnBla.07: Conference on regional innovation—Central Switzerland, http://www.2007.unbla.org/ [Date of access: May 02, 2008].

unBla Team (2007c). UnBla.07 Conference documentation, http://www.2007.unbla.org/UnBla.07.pdf [Date of access: October 24, 2007].

Weinstein, Krystyna (1998). Action learning: A practical guide. Aldershot: Gower Publishing Limited.

Weirauch, Wolfgang (2002). Ich glaube an die Kraft der menschlichen Verbindung. Interview mit Robert Jungk. Münster: Mehr Demokratie, http://www.muenster.org/mehr-demokratie/archiv/l_12.htm [Date of access: May 02, 2008].

West, Casey (2004). Why you should attend a conference, http://www.oreillynet.com/onlamp/blog/2004/07/why_you_should_attend_a_confer.html [Date of access: May 02, 2008].

Wolf, Patricia (2003). Erfolgsmessung der Einführung von Wissensmanagement. Eine Evaluationsstudie im Projekt "Knowledge Management" der Mercedes-Benz Pkw-Entwicklung der DaimlerChrysler AG. Münster: Verlagshaus Monsenstein und Vannerdat.

Videos

Video_1: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_01_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_2: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_02_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_3: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_03_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_4: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_04_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_5: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_05_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_6: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_06_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_7: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_07_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_8: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_08_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_9: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_09_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_10: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_10_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_11: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_11_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_12: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_12_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_13: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_13_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_14: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_14_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_15: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_15_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_16: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_16_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_17: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_17_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Video_18: https://archive.org/embed/Unbla07-Clip14/Clip_18_s.mp4 (640 x 480)

Patricia WOLF, Prof. Dr. rer. pol., is Professor of General Management and Research Director of the Institute of Management and Regional Economics at Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts (Switzerland). At the same time, she is Assistant Professor at the Institute of Psychology of Work at ETH Zurich (Switzerland) and Visiting Professor of Knowledge and Innovation Management at University of Caxias dos Sul (Brazil). Patricia holds a doctor degree in Business Administration from University Witten Herdecke, Germany and is actually finishing her studies on Sociology, Philosophy, and Literature at FernUniversität Hagen, Germany. Her main research interests cover knowledge transformation and innovation management in social systems (regions, organisations, groups).Patricia WOLF is a founding member of unBla.

Contact:

Prof. Dr. Patricia Wolf

Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts

Institute of Management and Regional Economics

Zentralstr. 9

6002 Lucerne

Switzerland

Tel.: +41 41 228 41 62

E-mail: patricia.wolf@hslu.ch

Peter TROXLER, Dr. sc. techn., MSc ETH , works as a senior project manager for the Waag Society in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, the Dutch media lab and avant-garde think-tank in the fields of networked art in healthcare, culture, society and education. Peter has worked in academia as a researcher at ETH Zurich, Switzerland and as a research manager at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland. As a consultant, he supports organisations in the private and public sector building management systems for the knowledge economy. His main interests are cross-disciplinary issues at the interface of psychology, IT and engineering, management science, and civil society, and he is said to be a passionate facilitator.

Contact:

Dr. Peter Troxler

unBla

Beukelsdijk 74 B

3022 DJ Rotterdam

The Netherlands

Tel.: +31 625 444 606

E-mail: peter@unbla.org

URL: http://www.unBla.org/

Wolf, Patricia & Troxler, Peter (2008). The Proof of the Pudding is in the Eating—but What was the Pudding in the First Place?

A Proven Un-Conferencing Approach in Search of Its Theoretical Foundations [56 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 9(2), Art. 61,

http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0802614.

Revised: 1/2015