Volume 25, No. 2, Art. 12 – May 2024

Linking the Study of Social and Spatial Mobility. Reflections From Research on Subjective Social Positions in the Context of Migration to Germany

Lisa Bonfert

Abstract: To gain a more nuanced understanding of social mobility in a globalized world, in this article I suggest studying the link between social and spatial mobility by exploring social positions in relation to international migration. While migration is often portrayed as a gateway to social mobility, migration scholars have highlighted that transnational spaces and intersecting inequalities may shape social mobility in complex ways. However, little is known about the subjective experiences of spatial and social mobility. Therefore, based on a study of subjective social positions among people who have relocated to Germany, I discuss the implications for a research design that enables social scientists to assess social mobility in contexts of international migration and to explore the spatial dimension in shaping social mobility trajectories. Specifically, I will argue for linking empirical findings from narrative interviews with concepts of space, capitals, and social comparison as well as transnational and intersectional theories. As I will show, this way of inquiring into the social-spatial mobility nexus allows for investigating the complex ways in which spaces affect social mobility, and thus provides a promising gateway to better understand social mobility as a process shaped by both time and space.

Key words: migration; social mobility; transnationality, grounded theory methodology, social comparison; reference groups, capitals

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Linking Assessments of Social and Spatial Mobility

3. Capturing Social Mobility in Relation to Migration

4. Toward a Methodology for Assessing Social Mobility in Contexts of Migration

4.1 Theoretical sampling

4.2 Data collection: Assessing social positions in contexts of migration

4.2.1 Use and limitations of the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status

4.2.2 Toward a narrative approach

4.2.3 Researching experiences of migration and Blackness as a white non-migrant

4.3 Analyzing data: Linking social and spatial mobility

5. Conclusion

Understanding social mobility has been a key pursuit in the social sciences as researchers seek to shed light on the dynamics of social structures and social inequality (HEATH & LI, 2024). Generally, social mobility describes the changes that occur in a person's position in the social structures of society that arise from unequal distributions of resources and opportunities, thus indicating a change in that person's ability to access and manage resources within that structure (ibid.). However, a key aspect that is often overlooked in the study of social mobility is the role of international migration in shaping social structures and people's positions within them (FAIST, FRÖHLICH, STOCK & TUCCI, 2021). Hence, despite growing levels of international movement and a range of research on the global dimension of societies and social structures, assessments of social mobility continue to be placed predominantly in the context of countries—a practice that has been increasingly criticized as methodological nationalism (AMELINA, BOATCǍ, BONGAERTS & WEISS, 2021; MILANOVIC, 2016). Outside of migration research, the study of social structures and people's movements within them thus largely lacks consideration of the spatial dimension of social mobility. Against this background, I consider that linking the study of spatial and social mobility would be a promising starting point for gaining a better understanding of the contemporary dynamics of social inequalities in an increasingly globalized world (MILANOVIC, 2016). Therefore, based on my research on the subjective social positions of people who have relocated to Germany, in this article I discuss implications for a methodology that allows for inquiry into social mobility in relation to international migration. [1]

Against the background of contemporary phenomena such as globalization and postcolonial critique, numerous researchers from various disciplines have emphasized that social inequalities are a multidimensional, complex, and inherently global issue (AMELINA et al., 2021; CHAKRABARTY, 2000; WALBY, 2021). In this vein, migration researchers have argued for transnational approaches to conceptualizing societies and social structures with which they seek to account for the individual experiences and agency of people in an interconnected world (WEISS, 2021). Besides highlighting that social structures and mobility are by no means limited by country borders, migration researchers have also called into question the dominant notion of social positions as being determined by specific sets of socioeconomic variables (MANDERSCHEID, 2021; MAU & MEWES, 2008; RECCHI & FAVELL, 2011). Instead, they have shown that assessments of migratory movements and people's experiences bring to light the complex ways in which individuals interpret and experience social inequalities in different contexts (ANTHIAS, 2012; EVANS, KELLEY & KOLOSI, 1992). Therefore, cases of international migration provide a promising entry point for developing a more nuanced understanding of social mobility in times of growing international connectivity and intersecting inequalities (AMELINA, 2017). However, the links between social and spatial mobility continue to be a challenging topic of investigation (FAIST et al., 2021). [2]

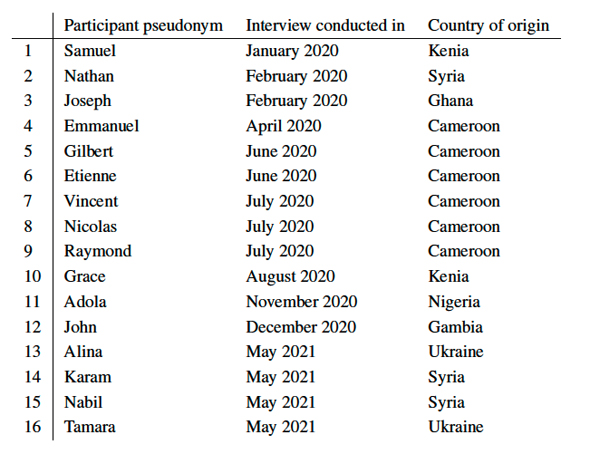

Against this backdrop, I engage in this article with the implications for a research design that enables social scientists to assess social mobility in connection with international migration and to explore the spatial dimension in shaping social mobility trajectories. Drawing on previous research and specifically my own study on social positioning as the process through which individuals evaluate their subjective social positions, I will highlight the potential of a grounded theory approach to investigating the perceptions of people who have experienced international migration using narrative interviews and coding techniques (CHARMAZ, 2006). As social mobility is an inherently quantitative field of research (NICO, 2021), I will therefore argue for qualitative methods that allow researchers to capture individual perspectives and experiences of social and spatial mobility. [3]

Following a brief account of the ways in which qualitative assessments in international settings have been shown to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of social mobility (Section 2), I will explain the use of space and capital as theoretical frameworks for conceptualizing social mobility in contexts of international migration (Section 3). Based on my study of 16 people who moved to Germany from various parts of the world, I will then discuss and reflect on my own process of sampling, data collection, and analysis to derive concrete implications for a study of social mobility that is sensitive to the role of space in shaping social positions (Section 4). In doing so, I will also show how theoretical concepts of social comparison (HYMAN & SINGER, 1968; MERTON, 1968), space, and capital (BOURDIEU, 1984 [1979], 1986 [1983]) can serve to incorporate spatial aspects into the study of social mobility, before concluding the article (Section 5). [4]

2. Linking Assessments of Social and Spatial Mobility

In the social sciences, social mobility is usually understood as the movement between social positions in the social structure of society (HEATH & LI, 2024). As such, it refers mainly to the changes that occur in people's positions in the social structure over time. To examine social mobility, researchers usually start from the premise that social structures and people's positions within them are determined by the distribution of socio-economic variables. Consequently, people's movements between social positions are attributed to a change in these variables, often with reference to developments across generations (HEATH & LI, 2024; MILANOVIC, 2016). [5]

However, as researchers have increasingly asked more open-ended questions in qualitative studies and begun to conduct cross-country comparisons, they have found that perceptions of social structures and the drivers of social mobility are not universal (EVANS et al., 1992; LINDEMANN & SAAR, 2014). In view of people's subjective social positions, scholars have thus highlighted that social mobility is importantly shaped by social norms and values (GOLDMAN, CORNMAN & CHANG, 2006; LINDEMANN, 2007; LINDEMANN & SAAR, 2014). As people position themselves by means of social comparison, their approaches to evaluating social mobility are strongly governed by the views and expectations associated with selected reference groups (HYMAN & SINGER, 1968; MERTON, 1968). Depending on the social context in which social comparison takes place, perceptions of social mobility can thus greatly vary (GOLDMAN et al., 2006; LINDEMANN & SAAR, 2014). In this sense, spatiality plays a key role in assessments of social mobility, as spaces may convey varying notions of social structure and positions within them (BOURDIEU, 1985). This raises important questions as to how social mobility unfolds as people move between spaces, and about the links between social and spatial mobility (FAIST et al., 2021). [6]

In the social sciences, social spaces as a framework for situating social structural analysis are often equalized with the geographical spaces of countries (NICO, 2021). While this suggests that social mobility is bound by country borders, migration and transnational researchers have shown that social positions develop not necessarily just within countries (JONSSON, 2020; STOCK & FRÖHLICH, 2021; WEISS, 2017). When individuals establish and maintain social relations with people in more than one country, these relationships can simultaneously serve as reference groups (ANTHIAS, 2016; BONFERT, BARGLOWSKI & FAIST, 2023). Against this background, transnational scholars have explored the transnational social spaces that emerge from these cross-border relations as an alternative unit of analysis to countries (GLICK SCHILLER, BASCH & BLANC-SZANTON, 1992; LEVITT, 2004). In the context of social mobility, these spaces have been argued to shape perceptions of social positions in complex ways (NIESWAND, 2011; RYE, 2019; WITTE & SCHMITZ, 2021). GOLDRING (1999, p.164), for example, suggested that,

"[...] the transnational social space, and the locality of origin, in particular, provide a special context in which people can improve their social position, make claims about their changing status and have it appropriately valorized, and participate in changing their place of origin so that it becomes more consistent with their changing expectations and statuses." [7]

However, scholars have also argued that social comparison with people in different countries promotes a "status paradox" with simultaneous and potentially conflicting social positions in different countries (NIESWAND, 2011; RYE, 2019). In the study of Central and Eastern European labor migrants in Coastland, Norway, for example, RYE (2019, p.38) found that a "dual frame of reference" promotes both "a downward social trajectory [...] and an upward social trajectory" in relation to the countries of origin and destination, respectively. [8]

In these works, researchers have especially emphasized the shift in reference group dynamics that occurs as individuals establish close relationships with people in more than one country simultaneously (LINDEMANN & SAAR, 2014). Because of the different values attached to the possible drivers of social mobility among different people, variations in reference groups thus also promote variations in social mobility not just within, but also across the geographical spaces of countries (GOLDMAN et al., 2006). It is precisely this change in the ways in which individuals engage in evaluating their own social position as they build and maintain relationships with people across spaces that has not received much attention (FAIST et al., 2021). Instead, assessments of social positions and mobility continue to be largely associated with societies in terms of countries (NICO, 2021). Therefore, important insights can be gained by exploring the experiences of people who establish connections internationally as they move and resettle from one country to another. This way of linking assessments of both social and spatial mobility experiences provides a promising starting point for a better understanding of how spatial changes contribute to social mobility as a process that unfolds not only over time but also across spaces (JONSSON, 2020; LINDEMANN & SAAR, 2014; WEISS, 2017). [9]

3. Capturing Social Mobility in Relation to Migration

To assess social mobility as the movement between social positions across time and space, I suggest drawing on theoretical considerations from BOURDIEU ([1979], 1985, 1986 [1983]). Based on empirical research, BOURDIEU proposed conceptualizing social structures in terms of social spaces that are structured along the distribution of capital. According to BOURDIEU (1986 [1983]), capital can take different forms, including economic, social, cultural, and symbolic capital. Social capital refers to the social relations through which individuals can access other forms of capital, while cultural capital includes incorporated knowledge and education, objectified goods such as books, and institutionalized forms such as degrees. Symbolic capital refers to the social recognition required for the conversion of cultural and social capitals into more tangible resources (ibid.). [10]

With this theory of capitals, BOURDIEU suggested that people's social position within a social space is determined by their abilities to use and transfer capitals into other forms that they consider relevant for achieving their life goals. Therefore, it allows for inquiring about subjective views towards the drivers of a person's own social mobility, as well as the potential changes to these views in relation to spatial movements. Accordingly, it also enables assessment of the social spaces in which individuals make their evaluations as they change their place of residence to a different country. Although social spaces are frequently equated with countries, BOURDIEU (1985, pp.723f.) proposed that social spaces be thought of as being "constructed on the basis of principles of differentiation or distribution." This constructivist perspective allows researchers to openly explore the spatial contexts in which people situate their own social position without presupposing the nature of the spaces involved. [11]

In migration and transnational research, scholars have commonly used national and transnational conceptions of space to show how they interact in shaping both access and evaluations of capitals in complex ways (FAIST et al., 2021; STOCK, 2023; WANG & SHEN, 2023). Cultural forms of capital, for example, can be difficult to transfer and valorize across countries, as their value is strongly determined by social norms, expectations, and institutions (EREL, 2010; SANTOS, 2020). While this may cause people to obtain employment that is perceived as "low-status" in their country of settlement, the ability to live and work in that country can be associated with capital attainment in the country of origin (KELLY & LUSIS, 2006, p.844). Consequently, people who move between countries are faced with varying logics of capital valuation, which also affects their own "socialised evaluation of capital" (p.845). [12]

Against this backdrop, researchers have emphasized people's involvement in transnational spaces as an important dimension in shaping capacities to validate capitals within and between countries (NOWICKA, 2013; RYE, 2019). NOWICKA (2013), for example, emphasized that degrees of transnational engagement are closely related to the convertibility of capitals between countries. Additionally, researchers underscored the impact of the structural conditions prevailing in people's countries of origin and destination and their embeddedness therein in determining opportunities for capital transfers (STOCK & FRÖHLICH, 2021). Furthermore, migration and transnationality have also been termed distinct forms of capital, which points to the value of being able to (not) move and maintaining transnational ties in accordance with a person's individual life goals (GERHARDS & HANS, 2013; TENEY & DEUTSCHMANN, 2018). [13]

Consequently, space has been shown to play a key role in shaping people's abilities to access and valorize capitals, while also affecting and possibly challenging the value attached to different forms of capital as determinants of social positions. However, these complexities are often overlooked in favor of a simplified portrayal of migration as a gateway for people to enhance and diversify their capital in a world of global inequalities (CHRISTIANSEN & JENSEN, 2019). Moreover, researchers have failed to explore how spaces are constructed and used for evaluating social mobility beyond the common focus on (trans)national spaces. Against this background, experiences of international migration provide an important contribution to a more nuanced understanding of the spatial dimension of social mobility (DE HAAS, CASTLES & MILLER, 2019). [14]

Therefore, I propose taking a bottom-up and agency-centered approach to investigating perceptions of social structures and social mobility based on the subjective interpretations and evaluations of people who have experienced migration (BASCH, GLICK SCHILLER & SZANTON BLANC, 2020; FAUSER et al., 2012; JONSSON, 2020). For this purpose, I consider BOURDIEU's (1984 [1979], 1985, 1986 [1983]) concepts of capitals and space a useful starting point for conceptualizing the drivers and situatedness of social mobility, as well as their relationship with each other (REED-DANAHAY, 2020). While a transnational perspective will serve to capture the case of international migration to scrutinize the role of countries in determining social mobility, I will also argue for an intersectional perspective toward social mobility (COLLINS, 2000; CRENSHAW, 1991; YUVAL-DAVIS, 2015). Rooted in feminist scholarship, the concept of intersectionality has been described as a standpoint theoretical approach to stratification theory. As such, scholars have argued for its value in assessing people's "positionings along socioeconomic grids of power; [...] people's experiential and identificatory perspectives of where they belong; and [...] their normative value systems" (YUVAL-DAVIS, 2015, p.94). Linking transnational and intersectional theories thus allows us to explore the individual ways in which people position themselves within and across spaces and in relation to the power dynamics inherent in these spaces in the context of global inequalities (AMELINA, 2017). [15]

4. Toward a Methodology for Assessing Social Mobility in Contexts of Migration

To gather new theoretical insights based on the standpoints of the people who participate in the research, grounded theory methodology provides a useful starting point (CHARMAZ, 2006; STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1998; TIMMERMANS & TAVORY, 2012). Taking a grounded theory approach means taking the narratives of the research participants as a point of departure to construct theoretical considerations through a circular process of collecting, analyzing and interpreting data (CHARMAZ, 2008). During this process, early findings serve to adapt and specify the research according to emerging themes and categories, allowing the researcher to select emerging points of interest for further exploration (EQUIT & HOHAGE, 2016; MEY & MRUCK, 2011). In the following pages, I will discuss and reflect on my study, in which I explored the links between social and spatial mobility using grounded theory methodology to derive implications and suggestions for future research on social mobility. After outlining the sampling strategy, I will reflect on the process of developing and adapting the methods for data collection. Finally, I will discuss the process of coding and analyzing the data in relation to the theoretical considerations of capitals and space, reference groups, transnationality, and intersectionality as outlined above. [16]

To develop a better understanding of the links between social and spatial mobility, I started from the premise that international migration is often associated with opportunities for an improved social position, especially when people move to more affluent countries. Therefore, I chose to explore the experiences of people whose migration might be similarly associated with an improvement in their social position. Being located in Germany at the time, I decided for practical reasons to focus on migration to Germany as an important destination country of international migration, especially for people who are seeking better opportunities and quality of life (OECD, 2023; STATISTISCHES BUNDESAMT, 2024). To narrow down the initial sample further without employing predefined variables, I used the Human Development Index (HDI)1) as a heuristic. Thus, I selected research participants based on their origins in countries with a relatively lower HDI score compared to Germany as their country of settlement. [17]

In the spirit of grounded theory methodology, I engaged in theoretical sampling techniques. This approach to identifying and selecting research participants suggests starting rather broadly with a range of different people and an open mind (GLASER & STRAUSS, 1967; MEY & MRUCK, 2011). Depending on the insights gained from coding and categorizing the data collected at this early stage of the research, the researcher selects the subsequent research participants with the goal of maximizing opportunities to establish concepts and identify differences and similarities between them (STRAUSS & CORBIN, 1998). Following four exploratory interviews with people I recruited through convenience sampling in early 2020, I decided to concentrate on the experiences of individuals from my own generation, who were still in the process of building their adult lives as students and apprentices or recent graduates. At this point, snowball sampling (PARKER, SCOTT & GEDDES, 2019) provided a useful approach to participant recruitment, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Having focused on people with origins in African countries, I recruited four more participants from Syria and Ukraine as contrasting cases through a German scholarship network. [18]

According to STRAUSS and CORBIN (1998), the circular process of collecting and analyzing data comes to an end when the researcher reaches the point of theoretical saturation, i.e., when additional data collection is not expected to contribute new insights on already developed categories and theoretical considerations. Having narrowed down the study as outlined above, I now considered this point to be reached. These 16 participants' experiences provided the basis for exploring the complex ways in which spatial movements can shape social mobility trajectories (for an overview of the sample, see Table 1).

Table 1: Overview of research participants [19]

In view of the sample, it is important to note that all research participants were currently embedded in the German education system or labor market and, therefore, were in possession of a (temporary) residence permit. Moreover, given the information that they provided regarding their families' living and working situations in their countries of origin, their backgrounds could be largely described as middle-class. The decision to migrate was often made by family members or by the participants themselves in the hope of a better future. These specifics importantly shape the results, as insecurities related to residency and poverty were currently not an issue. Therefore, I consider further exploration of subjective social positions among people with different trajectories and at different points in their lives an important contribution to the future study of social mobility. Additionally, including immobile people in the sample could provide a useful approach to gaining more nuanced insights on the roles of migration and transnationality and the spatial dimension of social mobility. [20]

4.2 Data collection: Assessing social positions in contexts of migration

To collect data on the development of subjective social positions in relation to migration, I chose interviews as a method to stimulate narrations about the understandings of my research participants and their evaluations of their social positions. Following the premises of grounded theory methodology, I thus sought to construct theoretical insights based on the ways in which my research participants evaluated their own social positions in an interview. Depending on their preferences, I conducted the interviews in either German or English. Although I had initially planned to engage more closely and longer-term with my research participants using ethnographic methods, the restrictions imposed because of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 required a change to digital interviewing using video calls. In the process of collecting and analyzing data, I therefore gradually adapted my strategy of asking questions and stimulating narrations both to the context of digital interviews and to the limitations that I encountered. [21]

4.2.1 Use and limitations of the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status

At first, I was faced with the general challenge of finding a suitable approach to assessing subjective social positions in connection with migration without predetermining the meaning and determinants of social positions or emphasizing the person's migration experience. In search of inspiration, I found that researchers who previously inquired about subjective social positions had often presented their research participants with a visual image of a social structure and asked them to depict and evaluate their own location in this image (EVANS et al., 1992; GOLDMAN et al., 2006). According to various scholars, a particularly useful image for qualitative research is the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status, which resembles a ladder with ten numbered rungs (ADLER, EPEL, CASTELLAZZO & ICKOVICS, 2000; SINGH-MANOUX, ADLER & MARMOT, 2003). As it does not contain any references to the specifics of social categories or space, I decided to try using this image in my interviews. [22]

To capture the development of social positions over time, I prepared a set of guiding questions as a basis for semi-structured interviews. Specifically, I included questions on 1. the social positions of my participants at present; 2. their social positions before moving to Germany; 3. their transnational involvement; and 4. their evaluation of the changes they had experienced regarding their social position. In this way, I hoped to gain insight into both the spaces in which they situated their assessment and the determinants that they considered relevant in shaping their social positions. Moreover, I aimed to ask more specifically about my participants' transnational engagement to gain insights on the possible role of transnational social spaces and transnationality (NOWICKA, 2013; STOCK & FRÖHLICH, 2021). [23]

With these questions and an image of a ladder with ten numbered rungs, I conducted the first four interviews. After an introductory conversation, I used the MacArthur Scale as an entry point to the interview, which I introduced as one possible way of depicting society where people may occupy various locations, before asking participants to indicate and evaluate their own position. As I conducted and analyzed these first interviews, however, I realized that the image and my introduction of it as a visual depiction of society was immediately associated with countries, as they asked whether I was referring to their countries of origin or to Germany. Although I returned the question and asked them where they would position themselves, I found that I was unable to capture the spaces of social mobility beyond their geographical connotation. [24]

4.2.2 Toward a narrative approach

To avoid predefining spaces in this way, I therefore decided to explore my participants' social spaces in the context of their own social realities. To this end, I excluded the MacArthur Scale from the following interviews and developed an interview guideline with which I could pursue a more narrative approach to interviewing (SCHÜTZE, 1982). Moreover, I avoided references to countries or to the term "society," unless my participants made these associations themselves. Instead, I phrased my questions about social positions in relation to the terms that they used in their interviews. In this way, I aimed to create a dialogue that "may help us understand how a phenomenon or particular life situation can be discussed, analyzed, and interpreted by the interview participants" (TANGGAARD, 2009, p.1511). [25]

Against the background of the first interviews, I decided to start the subsequent ones by asking my participants about their last big success. "Success" had emerged as a major category related to understandings of social mobility in previous interviews. This introductory question now served as a starting point for getting my participants to talk about their personal lives and the things they considered important. Second, I asked them whom they had first talked to about this success, before asking further questions about the people in their lives. As I tried to depict my participants' social environments in this way, I sought to gain an understanding of the social spaces at play (HYMAN & SINGER, 1968; KIESLINGER, KORDEL & WEIDINGER, 2020). Third, I decided to ask my participants directly what they personally associated with the term "social position." Based on their explanations, I then asked them to elaborate on their own position and paid attention to both what they considered to determine their social position and the people and places they referred to. [26]

As I analyzed these interviews, I found the narrative approach to interviewing a useful basis for exploring the frameworks and determinants involved in social positioning within and across spaces, which were rooted in the subjective understandings and estimations of every research participant with whom I was able to speak (PRZYBORSKI & WOHLRAB-SAHR, 2014). As I will show in Section 4.3, this way of engaging with each participant's individual perspective allows for a nuanced analysis of social mobility, which I consider a promising avenue for further research in this field (CEDERBERG, 2017). [27]

4.2.3 Researching experiences of migration and Blackness as a white non-migrant

The different interviews I conducted between early 2020 and 2021 each lasted one to two hours. Despite the obstacles that researchers have raised in relation to data collection from a distance (DEAKIN & WAKEFIELD, 2014; WELLER, 2017), I was able to facilitate a relaxed and friendly atmosphere in which my participants were open to share their experiences with me. This is probably due to their personal acquaintance and familiarity with digital technologies and our similarities in terms of age, education, and life stage, as I was also enrolled at university when I conducted the study. However, the ways in which my research participants presented themselves and expressed their experiences was also importantly shaped by our differences, especially in terms of origin and skin color. In the spirit of a constructivist approach to grounded theory methodology, I aimed to take a reflexive position and continuously questioned my own position and perspectives as influencing factors on the research (CHARMAZ, 2006, 2011). Overall, it is important to note that global power hierarchies significantly contribute to the ways in which my research participants presented themselves to me, a white female researcher with no migration experience (NOWICKA & RYAN, 2015). Consequently, their positioning during the interviews was shaped by the expectations and assumptions they associated with me. [28]

To critically reflect on this and to ensure that the perspectives of my participants were considered as much as possible in the research process, I initiated post-interview conversations with Emmanuel and Gilbert.2) They both offered to discuss their interview experiences with me, which enabled me to ask them for their thoughts both on the interview and possible alternative approaches to asking questions and on the ways in which they would interpret their own responses. It was Emmanuel's reflection on his interview that initiated my decision to abandon the MacArthur Scale to better capture the spatial dimension of social mobility from my research participants' perspectives, and it was Gilbert who suggested asking directly about my participants' understandings of social position. This way of involving research participants in the research process allows for a critical reflection on researchers' assumptions and their role in shaping the research (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012). While the following depiction of my approach to conducting data analysis is thus naturally driven by my personal views, experiences, and prejudices, I made a conscious effort to continuously build on the interpretations and concepts used by my participants (CHARMAZ, 2011). [29]

4.3 Analyzing data: Linking social and spatial mobility

In line with grounded theory methodology, I transcribed and coded each audio-recorded interview before conducting the next. Using the computer program f4analyse, I started with initial line-by-line coding and gradually sorted and merged codes into categories by means of focused and axial coding (CHARMAZ, 2006; GLASER & STRAUSS, 1967). Using abduction as a guiding principle, this data analysis process was inspired by the literature and theoretical ideas outlined earlier in this article (CHARMAZ, 2006; DUNNE, 2011). By linking the analysis of my participants' points of reference and their choice of capitals as social position criteria, I identified four main ways in which these aspects interact in shaping social mobility. In the following pages, I will demonstrate how analyzing the interplay between reference groups and capitals sheds light on this multilayered role that spaces can play in processes of social mobility. [30]

In view of the references that my participants made, I found that most of them used geographical spaces to situate their social mobility assessments. Thus, when describing the development of their social position, they often compared their position with reference to their countries of origin and settlement, respectively. However, looking at the capitals they used to describe their position, I found that these comparisons took different forms which illuminates different facets of the spatial dimension of social mobility. On the one hand, some participants evaluated their position by comparing their changed access and control over capitals before and after they moved to Germany. These participants identified certain capitals as determinants of their social position and pondered how their abilities to access and use them had changed since they left their countries of origin. This way of comparing geographically defined spaces in terms of countries resonates with the conventional notion of social mobility in terms of changed access to resources over time, where spatial movements to a different country may provide access to different resources (CHRISTIANSEN & JENSEN, 2019; MILANOVIC, 2016). [31]

On the other hand, countries also served as points of reference for comparing different logics of capital valorization (EREL & RYAN, 2019; GOLDMAN et al., 2006). In my study, this form of spatial comparison was linked to perceptions of varying social positions in different spaces at the same time, which is reminiscent of what NIESWAND (2011) termed the "status paradox." For example, Emmanuel, who had moved to Germany from Cameroon to pursue a Ph.D. in German philology, emphasized the unprecedented ways in which his skin color and gender became key interrelated factors determining his abilities to valorize his capital in Germany.

"I would say, the ways in which people perceive of me, is firstly as a Black person, a Black man, an African man, too. And then if you add things like being a doctoral student and so on, it becomes a bit more nuanced, I would say." [32]

From Emmanuel's perspective, the linkage between his ascribed ethnicity and his gender plays a major role in determining his social position in Germany. As he argued, this link frequently caused people to think of him as a refugee and a criminal. Specifically, he considered this image as a "Black man" to limit his opportunities both to valorize and to accumulate new capital in Germany. In this sense, the combination of ethnicity and gender is essentially perceived as "blocking" the potential for social mobility in Germany. He also emphasized the amount of energy it took to unblock this potential, and the constant exertion from trying to valorize his capital by making people see beyond his outward appearance. In the face of these difficulties, he considered his social position to have diminished since moving to Germany. However, when comparing this experience in Germany with Cameroon, it becomes apparent that Emmanuel considered social mobility to unfold differently in different spaces.

"In Germany, skin color is a difference—something that really makes a difference. And at home, skin color does not come into play. But other things, entirely. [...] I think people [in Cameroon] actually perceived me as a person, as an individual and not as a member of an ethnic group. [...] And you could even imagine that, especially because someone is from Europe, that you can also improve your position in society a little. [...] So, when a Cameroonian came back home, I would imagine that their position, I mean other people's perspectives towards him, would change, in the sense of improve." [33]

On the one hand, Emmanuel emphasized that his social position in Cameroon was subject to the same achievements that he found so difficult to demonstrate in Germany, later referring specifically to his educational attainments and professional experience. On the other hand, he pointed to the ways in which moving to a different part of the world can become a distinct form of capital, where the ability to migrate may also affect social mobility (EREL, 2010). This points to the simultaneity of different forms of social mobility in different geographically defined spaces, commonly referred to as the "status paradox," which is shaped by the different ways in which capitals can be valorized and accessed within these spaces (NIESWAND, 2011; RYE, 2019). Similarly, various participants in my study described how accumulating cultural capital, including migration-specific capital, promoted an improved social position in relation to their countries of origin, while failing to do the same in Germany—a phenomenon also previously articulated in research, especially on skilled migration (EREL, 2010; KOFMANN & RAGHURAM, 2006). This highlights how intersecting inequalities play out differently in different geographical spaces and thus affect social mobility in diverse ways. Consequently, to better understand processes of social mobility, it is important to consider the countries at play within the global power dynamics that unfold in the face of international migration. As Emmanuel's example shows, in contexts of international migration, the ability to valorize and accumulate capital can be significantly altered by intersecting inequalities such as ethnicity and gender (YUVAL-DAVIS, 2015). In this way, the geographical spaces involved in migration play a relevant role in the emergence of a "status paradox" (NIESWAND, 2011). [34]

Yet another spatially comparative approach to social positioning was evident among those participants who used their countries of origin and destination as points of reference for (re)evaluating their own views towards capitals. As they compared their perceptions now to when they had lived in their countries of origin a few years back, they identified more fundamental changes in how they defined their goals and the capitals they considered necessary for achieving them. Although these participants also placed their social position within their countries of origin and destination, they evaluated their social mobility in direct relation to their spatial mobility and how it had impacted their views. Here, social mobility is driven by changing considerations of what constitutes capital as a driver of social mobility more generally, rather than changes in access or abilities to valorize capital. This was evident, for example, in Gilbert's narrative, as he described how his initial goal of having a family of his own lost importance as he began to focus on professional goals when moving to Germany.

"If I had stayed in Cameroon, then I would probably have fulfilled 80 percent of the expectations that I used to have as a child. That means, if I had stayed in Cameroon, I would probably already have a child, at least, or maybe a wife. And, in my head, I would be older than I feel right now." [35]

This highlights how migration can challenge a person's views and subsequent approach to evaluating their social position. Despite the lack of a family, Gilbert considered his social position to have improved based on educational and professional criteria that had gained relevance to him. Similarly, various participants pondered how their personal views and goals in life had changed since they moved to Germany. This was largely attributed to their exposure to a different way of thinking associated with another country, with international migration representing a distinct resource that allowed them to consciously reflect on the meaning and value of capitals for them personally. Therefore, they found that they now also evaluated their social position differently, with their social mobility being largely subject to their changed views. [36]

These different ways of comparing countries of origin and settlement as distinct points of reference and spaces for situating evaluations of social mobility are importantly characterized by varying degrees of transnationality in the context of different experiences of intersecting inequalities (AMELINA, 2017; BARGLOWSKI, 2019; FAUSER et al., 2012). While the geographical spaces of countries serve as a basis for comparison and evaluation, the linkages that emerged between these geographical spaces as my participants moved from one to the other and the relational spaces that they produced play a key role in shaping the forms of social mobility outlined above (REED-DANAHAY, 2020). According to my findings, the "status paradox" based on varying logics of capital valorization in different geographical spaces in terms of countries is linked to comparatively high degrees of transnationality. Here, strong attachments to the country of origin stand in contrast to the inequalities experienced in the country of settlement. Thus, the emergence of the transnational social space in which these participants simultaneously experience conflicting abilities of capital valorization promotes perceptions of multiple social positions in relation to the geographical spaces at play. In the other two cases, comparatively lower degrees of transnationality were linked to stronger attachments to the country of settlement and more coherent experiences of social mobility. The transnational space that emerged from these participants' simultaneous connections to their countries of origin and destination became a venue for the experienced changes regarding abilities to valorize capital, on the one hand, and perceptions towards the meaning and value of capitals, on the other. In this sense, transnationality may be both a cause and an effect of the ways in which people experience inequalities and subsequent difficulties within the geographical spaces of countries. [37]

Although the comparative approach to social positioning, with social positions associated directly with countries, was the most prominent in my study, I also found evidence for a form of social mobility that can be attributed more directly to transnational social spaces. This was the case among participants who evaluated their social position in relation to people rather than places, thus situating their evaluation in relationally defined social spaces (KIESLINGER et al., 2020; REED-DANAHAY, 2020). Here, the choice of capitals for evaluating social positions did not follow any comparative logic, as was the case in the other interviews. Instead, participants who positioned themselves in this way identified a range of capitals, especially social and cultural forms, and evaluated their position based on their changed abilities to access and use these capitals over time. While the relational space was used for situating social mobility, space was here not argued to influence social positions in any specific way. In contrast to the comparative approaches to social mobility outlined above, this perspective is characterized by high levels of spatial mobility and transnationality. Consequently, transnational involvement can shape social mobility in numerous ways, which highlights the importance of future research on the role of both geographical and relational spaces in affecting social mobility trajectories (STOCK, 2023; STOCK & FRÖHLICH, 2021). [38]

While studies on social mobility continue to focus primarily on the changes that occur in people's social positions within countries (NICO, 2021), in this article, I have proposed a methodology for investigating social mobility in the context of international migration. Specifically, I have shown how studying subjective social positions by inquiring into reference group dynamics in relation to the selection and evaluation of capitals as the drivers of social mobility provides an opportunity to dive deeper into the complex links between spatial and social movements. Therefore, I highlighted that the experiences of people who have relocated to a different country provide relevant insights into the complexity of social mobility in a globalized world (FAIST et al., 2021). Based on a critical discussion of my research on the subjective social positions of people who had relocated to Germany, I discussed the methodological challenges and implications for the contemporary study of social mobility. To incorporate the spatial dimension and better understand how it affects processes of social mobility, I proposed conducting narrative interviews, which would help researchers to explore the spaces in which people encounter and situate social mobility and to identify which aspects they consider to be shaping their social position. Specifically, I suggested stimulating narratives that would allow research participants to describe their social surroundings, as well as their own understandings and evaluation of their social position. To conceptualize the empirical findings, I proposed linking them with BOURDIEU's (1984 [1979], 1985, 1986 [1983]) theories of space and capitals, theories of social comparison and reference groups, as well as transnational and intersectional theories (GLICK SCHILLER et al., 1992; HYMAN & SINGER, 1968; YUVAL-DAVIS, 2015). [39]

This way of exploring social mobility allows examination of the complex ways in which social positions evolve, not just over time but also in relation to space. On the one hand, I have shown how spatial comparisons induced by international migration reveal a variety of ways in which both geographical and relational spaces shape social mobility by affecting not only access and control, but also perceptions toward capitals (EREL, 2010; GOLDMAN et al., 2006). While international movements may therefore initiate changes in these aspects and thus contribute to social mobility over time, they can also promote a "status paradox" with experiences of multiple social positions in different geographical spaces (NIESWAND, 2011). In light of reference group dynamics and capital valuations in comparative approaches to social positioning, this is especially the case when ascribed markers of social position gain relevance in shaping the experienced potential for accessing and valorizing capitals in the country of settlement (LINDEMANN, 2007; RYE, 2019; SANTOS, 2020). This points to the complex ways in which the power structures inherent in national spaces shape opportunities and reinforce inequalities (DE HAAS, 2021). Therefore, studying international migration contexts contributes significantly to highlighting the role of global power dynamics in affecting social mobility and experiences of intersecting inequalities (YUVAL-DAVIS, 2015). While fostering a positive image of affluent receiving countries such as Germany and subsequent portrayals of international migration as a pathway for improvement, global power structures also promote experiences of social exclusion by emphasizing various intersecting social divisions (ibid.). In my findings, experiences of a "status paradox" are closely linked to relatively high levels of transnationality coupled with strong notions of social exclusion in the country of destination. This points to the important links between transnationality and intersectionality in social mobility trajectories, which need further exploration in future research (AMELINA & BARGLOWSKI, 2018; ANTHIAS, 2012). [40]

On the other hand, I have also shown how the proposed methodology for studying the links between social and spatial mobility sheds light on another transnational dimension of social mobility in which social mobility is situated in relation to people rather than geographical spaces (SKLAIR, 2001; STOCK, 2023). Thus, I also found that social positioning can take place without references to countries. In the absence of spatial comparisons, the choice and evaluation of capitals is directly related to people, thus emphasizing the relational element of space (KIESLINGER et al., 2020; REED-DANAHAY, 2020). Here, high degrees of transnationality are accompanied by high attachments to the transnational social space in which social mobility is assessed. [41]

In the context of these findings, I consider qualitative assessments of the social-spatial mobility nexus to offer a useful gateway to better understand social mobility as a process shaped by both time and space. To better discern the potential role of international migration and transnationality in social mobility trajectories, studying a range of experiences of people with and without histories of migration provides a promising venture for future research. While my study was importantly limited by restrictions to personal encounters, I would further argue for ethnographic research methods that enable greater and longer-term engagement with research participants to develop more in-depth insights into their lifeworlds (BEHRENDS, 2024). This way of investigating social mobility by inquiring into people's personal perspectives and realities can contribute relevant insights to the study of social mobility beyond predefined categories. [42]

I would like to thank all participants who took part in my research, as well as two anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

1) The HDI is a measure of human development initiated by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) based on assessments of people's abilities to live a long and healthy life, to access education and to obtain a decent standard of living (HERRE & ARRIAGADA, 2023). <back>

2) All names used with reference to my research participants are pseudonyms. <back>

Adler, Nancy; Epel, Elissa S.; Castellazzo, Grace & Ickovics, Jeannette R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology, 19(6), 586-592.

Amelina, Anna (2017). Transnationalizing inequalities in Europe: Sociocultural boundaries, assemblages and regimes of intersection. New York, NY: Routledge.

Amelina, Anna & Barglowski, Karolina (2018). Key methodological tools for diaspora studies: Combining the transnational and intersectional approaches. In Robin Cohen & Carolin Fischer (Eds.), Routledge handbook of diaspora studies (pp.31-39). London: Routledge.

Amelina, Anna; Boatcǎ, Manuela; Bongaerts, Gregor & Weiß, Anja (2021). Theorizing societalization across borders: Globality, transnationality, postcoloniality. Current Sociology, 69(3), 303-314, https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120952119 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Anthias, Floya (2012). Transnational mobilities, migration research and intersectionality. Nordic Journal of Migration Research, 2(2), 102-110, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/48711216 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Anthias, Floya (2016). Interconnecting boundaries of identity and belonging and hierarchy-making within transnational mobility studies: Framing inequalities. Current Sociology, 64(2), 172-190.

Barglowski, Karolina (2019). Cultures of transnationality in European migration: Subjectivity, family and inequality. London: Routledge.

Basch, Linda; Glick Schiller, Nina & Szanton Blanc, Christina (2020). Nations unbound: Transnational projects, postcolonial predicaments and deterritorialized nation-states. London: Routledge.

Behrends, Andrea (2024). Lifeworlds in crisis: Making refugees in the Chad-Sudan borderlands. London: Hurst & Company.

Bergold, Jarg & Thomas, Stefan (2012). Participatory research methods: A methodological approach in motion. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), Art. 30, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-13.1.1801 [Accessed: May 16, 2024].

Bonfert, Lisa; Barglowski, Karolina & Faist, Thomas (2023). Transnational social positioning through a family lens: How cross‐border family relations shape subjective social positions in migration contexts. Global Networks, e12468, http://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12468 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Bourdieu, Pierre (1984 [1979]). Distinction. A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1985). The social space and the genesis of groups. Theory and Society, 14(6), 723-744.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1986 [1983]). The forms of capital. In John Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp.241-258). New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

Cederberg, Maja (2017). Social class and international migration: Female migrants' narratives of social mobility and social status. Migration Studies, 5(2), 149-167.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh (2000). Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial thought and historical difference. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Charmaz, Kathy C. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Charmaz, Kathy C. (2008). Grounded theory as an emergent method. In Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber & Patricia Leavy (Eds.), The handbook of emergent methods (pp.155-172). New York, NY: Guilford.

Charmaz, Kathy C. (2011). Den Standpunkt verändern: Methoden der konstruktivistischen Grounded Theory. In Günter Mey & Katja Mruck (Eds.), Grounded Theory Reader (pp.181-205). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften

Christiansen, Christian Olaf & Jensen, Steven L.B. (2019). Introduction. In Christian Olaf Christiansen & Steven L.B. Jensen (Eds.), Histories of global inequality (pp.1-32). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Collins, Patricia Hill (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness and the politics of empowerment (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299.

de Haas, Hein (2021). A theory of migration: The aspirations-capabilities framework. Comparative Migration Studies, 9(1), 1-35, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-020-00210-4 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

de Haas, Hein; Castles, Stephen & Miller, Mark J. (2019). The age of migration: International population movements in the modern world (6th ed.). London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Deakin, Hannah & Wakefield, Kelly (2014). Skype interviewing: Reflections of two PhD researchers. Qualitative Research, 14(5), 603-616.

Dunne, Carian (2011). The place of the literature review in grounded research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 14(2), 111-124.

Equit, Claudia & Hohage, Christoph (Eds.) (2016). Handbuch Grounded Theory. Von der Methodologie zur Forschungspraxis. Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Erel, Umut (2010). Migrating cultural capital: Bourdieu in migration studies. Sociology, 44(4), 642-660.

Erel, Umut & Ryan, Louise (2019). Migrant capitals: Proposing a multi-level spatio-temporal analytical framework. Sociology, 53(2), 246-263, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518785298 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Evans, Mariah D.R.; Kelley, Jonathan & Kolosi, Tamas (1992). Images of class: Public perceptions in Hungary and Australia. American Sociological Review, 57(4), 461-482.

Faist, Thomas; Fröhlich, Joanna J.; Stock, Inka & Tucci, Ingrid (2021). Introduction: Migration and unequal positions in a transnational perspective. Social Inclusion, 9(1), 85-90, https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v9i1.4031 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Fauser, Margit; Voigtländer, Sven; Tuncer, Hidayet; Liebau, Elisabeth; Faist, Thomas & Razum, Oliver (2012). Transnationality and social inequalities of migrants in Germany. SFB 882 Working Paper Series, 11.

Gerhards, Jürgen & Hans, Silke (2013). Transnational human capital, education, and social inequality. Analyses of international student exchange. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 42(2), 99-117, https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2013-0203 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Glaser, Barney G. & Strauss, Anselm L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Glick Schiller, Nina; Basch, Linda & Blanc-Szanton, Cristina (1992). Transnationalism: A new analytic framework for understanding migration. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 645(1), 1-24.

Goldman, Noreen; Cornman, Jennifer C. & Chang, Ming-Cheng (2006). Measuring subjective social status: A case study of older Taiwanese. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 21, 71-89.

Goldring, Luin (1999). The power of status in transnational social fields. In Ludger Pries (Ed.), Migration and transnational social spaces (pp.162-186). Hampshire: Ashgate.

Heath, Anthony & Li, Yaojun (2024). Social mobility. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Herre, Bastian & Arriagada, Pablo (2023). The Human Development Index and related indices: What they are and what we can learn from them, https://ourworldindata.org/human-development-index [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Hyman, Herbert H. & Singer, Eleanor (Eds.) (1968). Readings in reference group theory and research. New York, NY: Free Press.

Jonsson, Stefan (2020). A society which is not: Political emergence and migrant agency. Current Sociology, 68(2), 204-222.

Kelly, Phillip & Lusis, Tom (2006). Migration and the transnational habitus: Evidence from Canada and the Philippines. Environment and Planning, 38(5), 831-847.

Kieslinger, Julia; Kordel, Stefan & Weidinger, Tobias (2020). Capturing meanings of place, time and social interaction when analyzing human (im)mobilities: Strengths and challenges of the application of (im)mobility biography. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 21(2), Art. 7, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-21.2.3347 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Kofmann, Eleonore & Raghuram, Parvati (2006). Gender and global labour migrants: Incorporating skilled workers. Antipode, 38(2), 282-303.

Levitt, Peggy (2004). Transnational migrants: When "home" means more than one country. Migration Information Source, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/transnational-migrants-when-home-means-more-one-country [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Lindemann, Kristina (2007). The impact of objective characteristics on subjective social position. Trames, 11(1), 54-68.

Lindemann, Kristina & Saar, Ellu (2014). Contextual effects on subjective social position: Evidence from European countries. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 55(1), 3-23.

Manderscheid, Katharina (2021). Concepts of society in official statistics. Perspectives from mobilities research and migration studies on the re-figuration of space and cross-cultural comparison. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 22(2), Art. 15, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.2.3719 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Mau, Steffen & Mewes, Jan (2008). Ungleiche Transnationalisierung? Zur gruppenspezifischen Einbindung in transnationale Interaktionen. In Peter A. Berger & Anja Weiß (Eds.), Transnationalisierung sozialer Ungleichheit (pp.259-282). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Merton, Robert K. (1968). Social theory and social structure. New York, NY: Free Press.

Mey, Günter & Mruck, Katja (Eds.) (2011). Grounded Theory Reader (2nd ed.). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Milanovic, Branko (2016). Global inequality: A new approach for the age of globalization. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nico, Magda (2021). Identity and change of a field: A literature analysis of the concept of social mobility. Social Science Information, 60(3), 457-478.

Nieswand, Boris (2011). Theorising transnational migration: The status paradox of migration. New York, NY: Routledge.

Nowicka, Magdalena (2013). Positioning strategies of Polish entrepreneurs in Germany: Transnationalizing Bourdieu's notion of capital. International Sociology, 28(1), 29-47.

Nowicka, Magdalena & Ryan, Louise (2015). Beyond insiders and outsiders in migration research: Rejecting a priori commonalities. Introduction to the FQS thematic section on "researcher, migrant, woman: Methodological implications of multiple positionalities in migration studies.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(2), Art. 18, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-16.2.2342 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

OECD (2023). Migration data brief (No. 9), https://www.oecd.org/migration/mig/Who-is-interested-and-plans-to-migrate-to-Germany-to-work-Migration-Data-Brief-July-2023.pdf [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Parker, Charlie; Scott, Sam & Geddes, Alistair (2019). Snowball sampling. In Paul Atkinson; Sara Delamont, Alexandru Cernat, Joseph W. Sakshaug & Richard A. Williams (Eds.), Sage research methods: Foundations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, https://eprints.glos.ac.uk/id/eprint/6781 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Przyborski, Aglaja & Wohlrab-Sahr, Monika (2014). Qualitative Sozialforschung. Ein Arbeitsbuch (4th ed.). München: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH.

Recchi, Ettore & Favell, Adrian (2011). Social mobility and spatial mobility. In Adrian Favell & Virginie Guiraudon (Eds.), Sociology of the European Union (pp.50-75). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Reed-Danahay, Deborah (2020). Bourdieu and social space. Mobilities, trajectories, emplacements. New York, NY: Berghahn Books.

Rye, Johan Frederik (2019). Transnational spaces of class: International migrants' multilocal, inconsistent and instable class positions. Current Sociology, 67(1), 27-46, https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392118793676 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Santos, Fabio (2020). Von Zentralafrika nach Brasilien und Französisch-Guyana: Transnationale Migration, globale Ungleichheit und das Streben nach Hoffnung. In Eva Bahl & Johannes Becker (Eds.), Global processes of flight and migration. The explanatory power of case studies / Globale Flucht- und Migrationsprozesse. Die Erklärungskraft von Fallstudien (pp.63-82). Göttingen: Göttingen University Press, https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/42940/1/GBSB4_becker.pdf#page=65 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Schütze, Fritz (1982). Narrative Repräsentation kollektiver Schicksalsbetroffenheit. In Eberhardt Lämmert (Ed.), Erzählforschung – Ein Symposium (pp.568-590). Stuttgart: Metzler.

Singh-Manoux, Archana; Adler, Nancy & Marmot, Michael (2003). Subjective social status: Its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Social Sciences and Medicine, 56(6), 1321-1333.

Sklair, Leslie (2001). The transnational capitalist class (Vol. 17). Oxford: Blackwell.

Statistisches Bundesamt (2024). Overview of external and internal migration, https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Society-Environment/Population/Migration/_node.html#sprg416794 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Stock, Inka (2023). Migrants' transnational social positioning strategies in the middle classes. Global Networks, e12444, https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12444 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Stock, Inka & Fröhlich, Joanna J. (2021). Migrants' social positioning strategies in transnational social spaces. Social Inclusion, 9(1), 91-103, https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v9i1.3584 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Strauss, Anselm L. & Corbin, Juliet M. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tanggaard, Lene (2009). The research interview as a dialogical context for the production of social life and personal narratives. Qualitative Inquiry, 15(19), 1498-1515.

Teney, Céline & Deutschmann, Emanuel (2018). Transnational social practices: A quantitative perspective. In Robert A. Scott, Stephen M. Kosslyn & Marlis C.B. Buchmann (Eds.), Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences (pp.1-15). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Timmermans, Stefan & Tavory, Iddo (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological Theory, 30(3), 167-186.

Walby, Sylvia (2021). Developing the concept of society: Institutional domains, regimes of inequalities and complex systems in a global era. Current Sociology, 69(3), 315-332, https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120932940 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Wang, Chenglong & Shen, Jianfa (2023). How subjective economic status matters: the reference-group effect on migrants' settlement intention in urban China. Asian Population Studies, 19(1), 105-123.

Weiß, Anja (2017). Soziologie Globaler Ungleichheiten. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Weiß, Anja (2021). Re-thinking society: How can sociological theories help us understand global and crossborder social contexts?. Current Sociology, 69(3), 333-351, https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120936314 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Weller, Susie (2017). Using internet video calls in qualitative (longitudinal) interviews: Some implications for rapport. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(6), 613-625.

Witte, Daniel & Schmitz, Andreas (2021). Relational sociology on a global scale: Field-theoretical perspectives on cross-cultural comparison and the re-figuration of space(s). Forum: Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 22(3), Art. 5, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-22.3.3772 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

Yuval-Davis, Nira (2015). Situated intersectionality and social inequality. Raisons Politiques, 2(58), 91-100, https://doi.org/10.3917/rai.058.0091 [Accessed: May 18, 2024].

|

Dr Lisa BONFERT is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Education and Social Work at the University of Luxembourg. In her research, she focuses on processes of migration and transnationalization, social inequalities, social protection, and transnational family dynamics. |

Contact: Dr Lisa Bonfert Université du Luxembourg, Belval Campus E-mail: lisa.bonfert@uni.lu |

Bonfert, Lisa (2024). Linking the study of social and spatial mobility. Reflections from research on subjective social positions in the context of migration to Germany [42 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 25(2), Art. 12, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-25.2.4155.