Volume 25, No. 3, Art. 12 – September 2024

Methodology and Empirics of Subject-Science Labor Research

Stefan Paulus

Abstract: A challenge in the research and assessment of psychosocial risks is to subjectively reflect on perceived work stresses as dynamic, i.e., changing and transactional risk constellations over time. In this article, I identify disciplinary challenges and research desiderata within the framework of subject-science labor research in order to subsequently present connections, problem-solving strategies, and approaches to take action. I conclude with insights into two research projects and a focus on the methodology of a model of subject-science labor research.

Key words: subject-science; labor research; psychosocial risk assessments; research programs

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The Status of Methodological Research Challenges

2.1 Challenge: The analysis of objective workloads and subjective work stresses

2.2 Challenge: Identification of interrelated stress factors in everyday life

2.3 Challenge: Capturing the time-dynamic evolution of psychosocial risks

3. Research Program of a Subject-Scientific Labor Research

3.1 Research interest

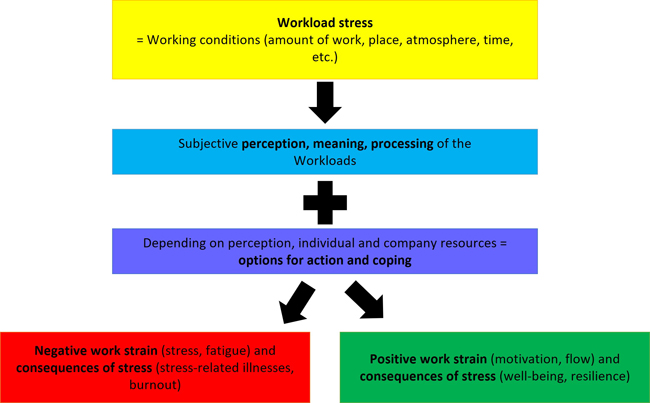

3.2 Premises

3.3 Research strategy

3.4 Heuristics

3.5 Auxiliary hypotheses

3.6 Methodological decisions

4. Model and Process of a Subject-Scientific Labor Research

4.1 Explicit modeling

4.2 Design of policies, measures and target agreements

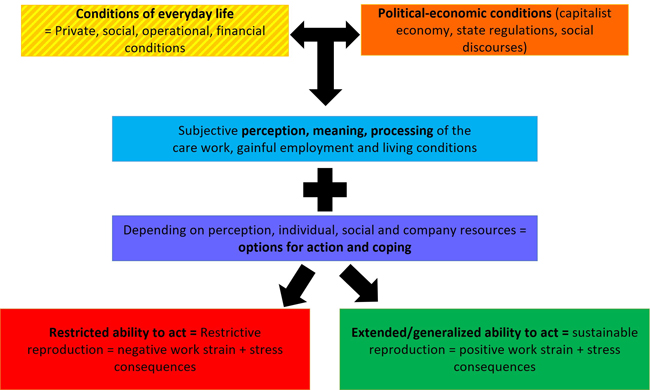

4.3 Self-exploration through problem identification and updating

5. Methodology and Empiricism of the Model and Process of Subject-Scientific Labor Research

5.1 Compatibility simulator

5.2 SELBA (Selbst Arbeitsbelastungen und Arbeitsbeanspruchungen erkennen, verstehen, verändern und monitoren) [I recognize, understand, change and monitor my own work stress and strains])

5.2.1 Step 1: Explicit modeling

5.2.2 Step 2: Policy design

5.2.3 Step 3: (Self-)Research and updating the risk constellation

6. Conclusion

The methodological problems in the interaction with "research subjects" or interviewees have already been addressed in an article published in FQS (PAULUS, 2015). In this context, it was concluded that the gap between researchers and interviewees led to vague evaluations of the interviewees' statements, such as their resistance to demanding working conditions due to differing concepts of resistance. As a result, the breakdown as well as analysis of reaction and coping strategies to power and domination relations could not be clearly clarified, because the risk of over-interpretation was too great. The interviewees had little interest in continuing to participate in the evaluation or even in socially transformative measures after the interviews (PAULUS, 2012). The conclusion I drew from this experience was to avoid paternalistic approaches or suggestions for action (e.g., how "oppressed" people should resist working conditions) in subsequent research projects and to focus on Forschung vom Subjektstandpunkt [research from the subject's point of view] as a method (HOLZKAMP, 1985; MARKARD, 1993). [1]

In the future, this should mean choosing a different research design—so that the framework conditions are already developed in such a way that they include strategies for expanding options for action. This has been investigated in various research projects in the context of the identification and assessment of psychosocial risks, including the workload of waste workers (FROSCH, MARTINY & PAULUS, 2014) and farmers (PAULUS, POHL, CHRIST, LOREZ-MEULI & RAVAGLI, 2021), work-life-balance problems of commercial vehicle mechanics (PAULUS, 2018a), and people with fatigue depression (PAULUS 2023). These frameworks were specified in the basic research project on psychosocial risks and subsequently tested as a formative risk assessment (PAULUS, SCHEIDEGGER, RABENSTEINER & EGGER, 2023). In the following Section 2, I focus on the methodology and methodological implementation of subject-science labor research. A key element here is, on the one hand, access to the recognition of workload and subjectively perceived job strain. On the other hand, the ability of project participants to take on a formative role as co-researchers in all steps of risk assessment plays an important role (MARKARD, 2000; PAULUS, 2022). [2]

Approaches and starting points for such intervening social research can already be found in various research traditions, such as the social science studies on the situation of the working class in England (ENGELS, 1952 [1845]), the questionnaire for workers (MARX, 1938), the instruments of co-investigation developed by Italian operaists, a movement of communists and anarchists (QUADERNI ROSSI, 1972 [1970]). Participants have also been assigned formative roles in action research approaches (LEWIN, 1948), community organizing (ALINSKY, 2010), community-based system dynamics (FORRESTER, 1961; HOVMAND, 2014), and participatory social research (BERGOLD & THOMAS, 2012; GRASSHOFF, 2018; VON UNGER, 2014). The history of social work has been influenced by such research perspectives (EICHINGER & WEBER, 2012; GRASSHOFF, RENKER & SCHRÖER, 2018). A common feature of these approaches is the promotion of the potential of the addressees through participatory cooperation models and the simultaneous examination of the role of the researchers through self-reflection. The strengthening of a collective capacity to act determines the principle of the methodological approach. This principle also describes social reasons and not individual deficits as the cause of the need for help or the limited ability to act (ANHORN, 2012; ARCIPRETE, 2015; KÖNGETER & SCHRÖER, 2013; PAULUS & GRUBENMANN, 2020). These principles have been obstructed at least since the early 1980s: Pedagogization, activation, therapeutic interventions, and individualization of problem situations, along with methodological institutionalism, have also contributed to a division between institutions, professions, and their target audiences (GRASSHOFF, 2015; SCHRÖER, 2013). In this regard, it seems more appropriate to assess research methods or the scope of social services based on their value to users, rather than their benefit to the labor market (HIRSCHFELD, 2012). This is where subject-science can make an important contribution, at least according to my first hypothesis. [3]

Based on the current state of knowledge in labor research and the disciplines involved (such as occupational science, occupational psychology, occupational sociology, occupational medicine, gender research, organizational pedagogy, etc.), another problem arises. Individual stress, strain factors, and coping with work stress are well documented for labor research (PAULUS, 2018b, 2022). At the same time, in the context of the (post-)Taylorist organization of production, labor science is described as a science of manipulation, since the aim is to discipline workers and optimize their work performance by means of mechanical or digital control mechanisms (FOUCAULT, 1977 [1975]; GROSKURTH & VOLPERT, 1975; PAULUS, 2017): The primary concerns in researching work capacity hazards and implementing risk assessments are that, despite the availability of a wide range of methods, many established procedures fail to fully address the specific requirements and needs of stressed individuals. Specifically, the quality of the current findings on risk assessment does not adequately reflect the importance of this information for effectively promoting occupational health and safety (BDP, 2023; BECK & LENHARDT, 2009). For this reason, the German Kommission Arbeit der Zukunft [Commission Labor of the Future], a commission of experts from the scientific community, from work councils of large companies, from trade unions and ministries, proposed not only higher implementation rates for risk assessments but above all the specification of standards and the development of models for the collection of risk assessments: Since forms of stress are diverse, situation-dependent and cannot be described and quantified uniformly, standards must be specified for specific industries and activities (JÜRGENS, HOFFMANN & SCHILDMANN, 2017). In this article I also focus on this model development. [4]

Combining approaches from labor and subject sciences to develop a unified model or methodology for assessing individual work hazards is essential. This is because labor sciences often overlook subjective experiences and lifestyle-specific aspects (PAULUS, 2018b, 2022), while subject sciences critique the dominance of economic motives in workforce optimization (OHM & VAN TREECK, 1990). [5]

There are further approaches to labor studies that focus on the Humanisierung der Arbeit (HdA) [humanization of work] and the critique of commodity-producing wage labor; they provide impetus for critical labor studies (BÖHLE & SENGHAAS-KNOBLOCH, 2020). Procedures in labor science for workforce optimization were critically evaluated in a number of publications, with a focus on everyday life as a crucial reference point for assessing workloads (e.g., BECK & BECK-GERNSHEIM, 2011; GOTTSCHALL & VOSS, 2003; HAUG, 2003; HOLZKAMP, 1995a; JÜRGENS, 2003, 2022; VOSS, 1991; VOSS & PONGRATZ, 1998; VOSS & WEISS, 2005; WINKER, 2011; WINKER & CARSTENSEN, 2007). In this context, I explore how labor research methods can be developed to examine everyday life problems, such as the burdens of gainful employment and care work1), alongside coping skills and strategies. The aim is to deduce how health-endangering constellations arise. Furthermore, it shall be examined how an assessment of risk constellations is possible through subject orientation. According to the second hypothesis of this article, the methodological and conceptual combination of labor research as well as subject-science can make an important contribution. [6]

In the following section, I first describe methodological approaches and challenges in relation to the desiderata of labor research and subject-science (Section 2). A particular focus is on the method of risk assessment as a procedure for identifying psychosocial risks in activities and for developing measures for risk reduction. In addition to clarifying the differences and connections between labor science and subject-science, a research program framework (Section 3) and a model of subject-scientific labor research (Section 4) are necessary for further action. I conclude with insights into the methodology and empiricism of subject-oriented labor research (Section 5). Accordingly, not only aspects of subject-oriented labor research are presented, but also conceptual, methodological, and empirical consequences in relation to research on the problems of everyday life. [7]

2. The Status of Methodological Research Challenges

The disciplines involved in the study of labor share a common focus: They assess the hazards of human work, including operational, physical, psychological, and sometimes private workloads. They also examine factors such as cooperation, operational resources, and the social, physical, as well as psychological management of these stresses and their effects. In the following context, it is particularly important to consider the conditions under which work is performed—both gainful employment and care work—as well as the Bedingungs-Bedeutungs-Begründungszusammenhänge [structural conditions, personal meanings, and justifications for action] that develop for the individual. The following section will first describe current methodological approaches and the challenges in order to formulate a framework for a subject-science labor research in the Section 3. [8]

2.1 Challenge: The analysis of objective workloads and subjective work stresses

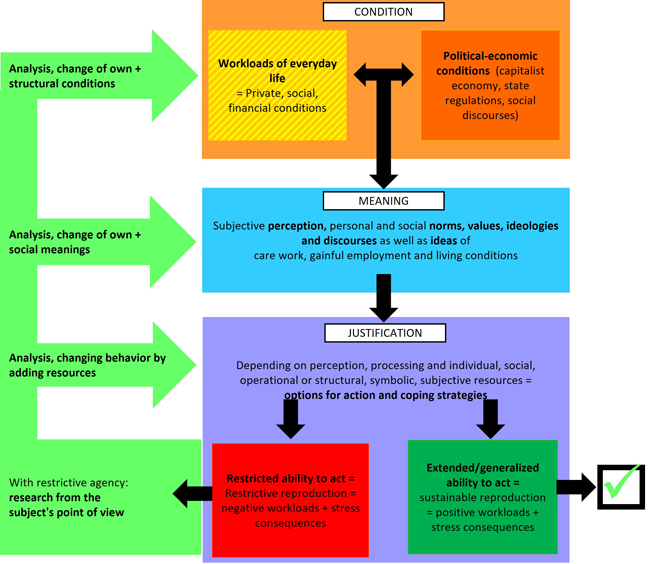

An example of the challenges of researching subjective perceptions is the risk assessment of noise as a workload: Hazard is understood as a source of work-related health impairment. The purpose of ergonomic risk assessments is to minimize health-threatening workloads. At the same time, risk assessments act as a stress monitor or an operational early warning system (HAHNZOG, 2015; JÜRGENS et al. 2017, p.156). There are a number of methods and guidelines for risk assessment, including for the psychosocial domain (EN ISO 12100, see also METZ & ROTHE, 2017). Mental stress is assessed using various questionnaires and measurement methods that have been tried and tested in labor science: Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ), European Workplace Assessment [EWOPLASS], Instrument zur stressbezogenen Tätigkeitsanalyse (ISTA) [Instrument for Stress-Related Activity Analysis], Kurzverfahren Psychische Belastung (KPB) [Brief Procedure for Mental Stress], Verfahren zur Ermittlung von Regulationserfordernissen und -hindernissen in der Arbeitstätigkeit (VERA/RHIA) [Procedure for determining regulatory requirements and obstacles in work activities]. The international standard EN ISO 10075, which describes guidelines for work design with regard to mental workload, formulates methodological requirements for measurement procedures, in particular their reliability and validity (BAUA, 2014). [9]

In labor science methods, noise is described as a mechanical force that depends on the duration and intensity of sound energy emitted from a source, rather than on the sensory processing by the listener: Average levels indicate a health risk and Deutsche Industrienorm (DIN) [German Industry Norm] standards regulate working conditions accordingly. For tolerable sound levels below the official exposure limit of 85 dB(A) (see DIN EN ISO 9612, Determination of the Noise Exposure Level in the Workplace), e.g., from keyboard clicks, telephone conversations, children's games, loud but not too loud beeps, etc., additional recording and assessment methods are required. Additional recording and assessment methods are needed to identify subjectively annoying and stress-inducing sounds, since noise exposure is difficult to control individually (i.e., it is generally not possible to turn off the sound) and also depends on individual disposition (whether the person is paying attention or not). Accordingly, qualitative experience and the subjective description of inadequate (acoustic) actual conditions are lacking in the recording and assessment of noise (PAULUS, 2019). [10]

In summary, a comprehensive range of risk assessment methods exists. There is still a deficit regarding the implementation of risk assessments, as many of the established methods do not meet the specific requirements of individual perceptions (BECK & LENHARDT, 2009; BECK, RICHTER, ERTEL & MORSCHHÄUSER, 2012; HÄGELE, ENGELS & FERTIG, 2019; JANETZKE & ERTEL, 2016; JÜRGENS et al., 2017). Conversely, this means that workloads, e.g., due to noise, have to be contextualized by the individual in order to enable comparisons, conclusions, or deductions based on descriptions or measurement data. In addition to psychoacoustic effects, subjectivity, socio-spatial perceptions, and interpretations (HOLZKAMP, 1973; MASCHEWSKY, 1983) become central to such a sensory analysis of auditory sensations. [11]

The subject-sciences assume that subjects exist in the plural, but not on average (MARKARD, 2000). Additionally, reality can be perceived, felt, and interpreted differently under the same social or economic conditions. Thus, the representation of social realities should be based on the perceptions and cognitive activities of individuals (HOLZKAMP, 1973). The perception of social reality is determined by individual life situations, learned strategies of action, mental models of reality, prejudices, and cultural coding. The partial controllability of the conditions of perception is pre-structured by social meanings and individual experiences. However, recognizing the partial controllability also opens the door to recognizing the constructed nature of perceptions and their social integration: Since workloads can produce different perceptions in different people, depending on the subjective way in which they are processed, they must be qualified as transactional (LAZARUS, 1999). Therefore, on a methodological level, it should be noted that objectively identical working conditions can evoke individually different feelings of stress or even diametrically opposed feelings of dis-stress or eustress (ROHMERT & RUTENFRANZ, 1975). From this, it can be concluded that the challenge in risk assessment is to reflect on perceptions and their social integration (PAULUS, 2016, 2018b). [12]

This challenge has been addressed in the Arbeitsbelastungs-/Arbeitsbeanspruchungskonzept [stress-strain concept of labor] science (ROHMERT, 1984; ROHMERT & RUTENFRANZ, 1975). ROHMERT and RUTENFRANZ (1975) defined correlations or chains of effects of stress/strain by stating that 1. general stress is caused by Arbeitsbelastungen [work stress] (e.g., work places, work processes, or the handling of work equipment); 2. positive and negative personal work stress develops as a result of subjective Wahrnehmung [individual perceptions and meanings]; 3. these depend on Handlungs- und Bewältigungsstrategien [coping strategies] (see also BÖHLE, 2010). Arbeitsbeanspruchung [work strain] is thus only the consequence of stress and its more or less successful processing. The same stress can lead to different levels of strains in different people. Depending on the type of stress and how well one subjectively copes with it, there may be short- or long-term negative as well as positive consequences.

Fig. 1: Stress-strain concept according to ROHMERT (1984), own illustration [13]

In summary, it can be said that the stress-strain concept cannot be used to derive health impairments directly: Stress can also produce stimulating factors (eustress), but individual stress factors can be identified. [14]

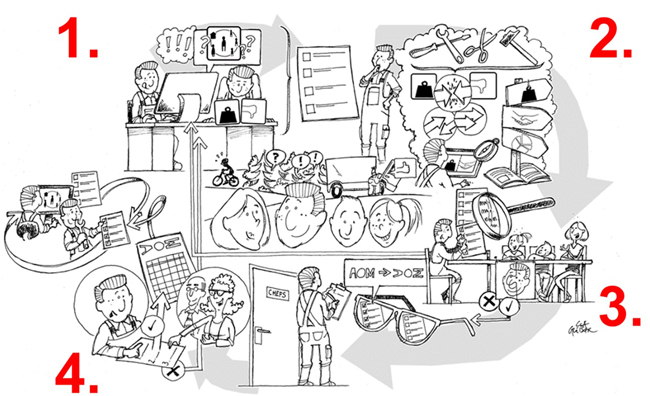

2.2 Challenge: Identification of interrelated stress factors in everyday life

On the basis of the subject-scientific theory of Prämissen-Gründe-Zusammenhänge [premise-justification connections] (HOLZKAMP, 1995b, p.24)2) and its concretization as Bedingungs-Bedeutungs-Begründungsanalyse [condition-meaning-justification analysis] (MARKARD, 2000, §11ff), further difficulties in the assessment of stress are described as follows. HOLZKAMP (1983) emphasized three central points in the empirical reconstruction of subjectivity as the overall social mediation of individual existence:

The capitalist social formation is not addressed to individuals in its totality but in the sections that concern them. However, the significance of individual elements cannot be understood directly, but only in terms of the overall social Bedingungen [conditions] and their reproduction.

For individuals, social conditions are understood as the meanings they attribute to these conditions. Bedeutungen [meanings] can be understood as socially produced possibilities and restrictions for action, which are experienced differently depending on life situations, individual resources, and biographical experiences. Subjects implement their own interests according to these principles: Conditions do not determine human action but are to be understood as 'meanings' that represent possibilities for action to which people can and must relate (MARKARD, 2000).

Actions are not arbitrary or solely determined by conditions; individuals always have reasons and justifications from their own perspective—Handlungsbegründungen [reasons and justifications for action]—that explain why they choose to pursue certain actions or not. An action is justified if it is stringent for me that I must (or should) act according to this intention in view of the given premise situation in order to safeguard my life interests (as I see them) (HOLZKAMP, 1995b). [15]

This figure of thought within the framework of the condition-meaning-justification analysis essentially offers the possibility of understanding how and why people who live under similar social material conditions interpret them in diverse ways and behave differently towards them. The primary task of subject-science is to analyze how social structures mediate the interaction between individuals and their living conditions. This involves examining how people, as creators of their own circumstances, relate to, suffer from, or benefit from these conditions, and how these interactions impact their ability to act (ibid.). This approach allows scholars to distinguish between two forms of agency within the framework of capitalist social formation: Restriktive/verallgemeinerte Handlungsfähigkeit [restrictive and generalized agency]:

Restrictive agency means settling down, coming to terms with the existing social conditions and, under these conditions, attempting to maintain a residual power of disposition and to participate at least partially in the existing power relations (HOLZKAMP, 1983, pp.376ff., 1997, p.397). Overcoming the restrictive capacity to act presupposes the ability to behave consciously towards (HOLZKAMP, 1997, p.394) social structures or the overcoming of the postulate of immediacy through categorical reconstruction of the connection between social and individual reproduction (p.390). Overcoming restrictive agency leads to extended and generalized agency.

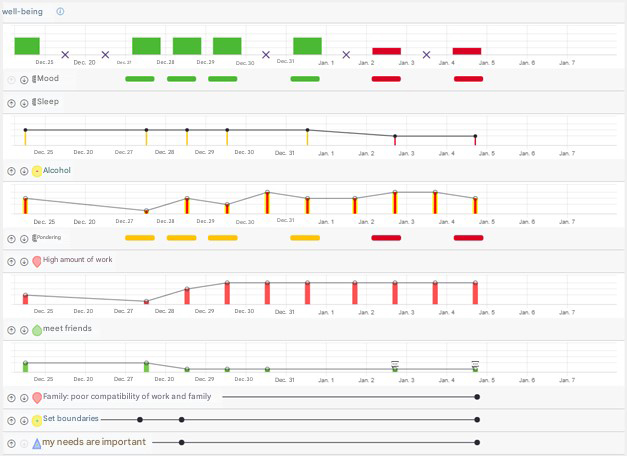

Extended or generalized agency involves transcending individuality in association with others with the general goal of conscious, self-controlled participation in and precautionary disposal of social-individual living conditions (HOLZKAMP, 1984a). [16]

For HOLZKAMP (1997), however, the terms restricted/restrictive and extended/generalized capacity to act/agency served not to typologize people, or to classify and exclude them—some people are generally capable of acting, others only restrictively—but they have the function of analyzing the concrete situation in each case to determine whether and in what way it enables us to expand our capacity to act and to overcome the conditions that stand in the way of agency, or whether we are thrown back or regress under the pressure of the current situation to attempts to secure our capacity to act within the framework of the prevailing conditions (p.396). [17]

If restrictions on stress- and anxiety-free participation in living conditions are subjectively perceived as such, and if opportunities for change are unavailable, this can impair both well-being and stress management strategies. Over time, it may also lead to negative long-term stress consequences: Subjective reasons for action play a substantial role in coping with everyday life. In the context of subject-science, the specific and determining factor of individual well-being is the establishment of individual participation in conscious and sustainable self-determination over social living conditions. Individual livelihood security can be equated with individual participation in social processes. This central development hypothesis leads to the conclusion that individuals can only co-determine their own living conditions in association with others. Conversely, individual living conditions are also relevant social living conditions. If individuals have no power to self-determine social living conditions, they remain at the mercy of the circumstances of existence. The lack of co-determination thus leads to restrictions on the ability to act, which in turn can be accompanied by self-harm (HOLZKAMP, 1983, p.372, 1984a, p.8). [18]

As an interim conclusion, both the subject-scientific approach and the stress-strain concept suggest that while the conditions and meanings of employment affect well-being, it is particularly the individual's methods of processing these factors that play a crucial role. Building on this insight, subject-scientific approaches highlight that the specific types and methods of everyday life—such as both paid work and care activities (self-care and caregiving)—have a decisive impact on whether stress outcomes are negative or positive (HOLZKAMP, 1995a). The analysis of potential hazards of the respective work force is thus directly linked to the reproduction of labor. The challenge for the specific organization of gainful employment is therefore to identify the resources of the working capacity and to promote those patterns of action that enable its sustainable reproduction. [19]

From a subject-scientific perspective, the reproduction of working capacity is therefore a target variable and the basis for a risk assessment. One challenge regarding this assessment lies in the fact that working capacity must be described as an existential and finite quantity. It is the epitome of the physical and mental abilities that exist in the body, the living personality of a person which they set in motion as often as they produce use values of any kind (MARX, 1975 [1867], p.181). The (re)production of the Arbeitskraft [labor power] is directed towards one's own labor power (self-care) and the labor power of relatives (care). Sustainable reproductive action therefore also requires trust in one's own ability to act. Additionally, the ability to self-regulate is necessary to effectively manage operational, temporal, financial conditions, and social relationships in ways that support the realization of one's own interests. This happens through the disposal of the sources of satisfaction, i.e., disposal over the conditions on which my life and development possibilities depend (HOLZKAMP, 1985, p.2). If individual reproductive action is not sustainable, it can impair the quality of work and life and jeopardize social status. Reproductive action therefore encompasses all skills and strategies that enable people to cope with demands that arise from the inherent logic of other forms of work, from social ties, from inner needs or from interactions between areas of life. This ability is thus conducive to employment as a worker in working life, and is influenced by logics of action that are not exhausted by an (explicit or implicit) employment orientation (JÜRGENS, 2006). [20]

Stressors arise in gainful employment and care work. These influence each other and have a negative or positive impact on the ability to act with regard to the reproduction of labor power. The concepts of restricted and generalized agency thus serve as analytical criteria for investigating agency. They also extend the criteria in the context of labor research with regard to the possibilities of overcoming constraints on agency in specific work situations:

Fig. 2: Condition-meaning-justification analysis of the reproduction of labor power (own illustration) [21]

For analyzing agency within the framework of condition-meaning-justification analysis, it is crucial to evaluate workloads to determine whether they lead to self-damaging coping strategies or if alternative actions can be implemented to proactively manage living conditions. Subjective reasons for action related to the reproduction of labor capital stem from the given set of premises and align with subjects' life interests. These reasons also arise from how subjects interpret and repeatedly justify their premises and life interests. The condition-meaning-justification analysis can be used to differentiate and analyze structural and symbolic obstacles to development as well as their subjective aspects of meaning, coping strategies, and justifications for action in the form of the ability to act. Simultaneously, the resources of agency are decisive in determining whether ideas of a good life can be implemented with regard to the reproduction of productive assets (PAULUS et al., 2023). Recognizing the causes of stress and the necessary cooperative prerequisites for the reproduction of labor power is crucial. In this context, subjects play a central role in regulating their own reproduction, which is essential for the sustainable reproduction of labor assets. [22]

2.3 Challenge: Capturing the time-dynamic evolution of psychosocial risks

If we consider the task of identifying the stresses of gainful employment in conjunction with life-situation-specific stress factors and their impacts, it follows that a risk constellation can be viewed as a complex, dynamic process. There are certain underlying structures and processes in work systems that influence each other and produce recurring, intensifying, weakening, or balancing life situations or hazard constellations over time. Once we look at the temporal-dynamic development of burnout illnesses in particular, those affected describe their own state of health as a downward trend over a longer period of time (in some cases many years). Those affected often speak of a self-reinforcing dynamic that leads to significant tipping points or moments of decompensation, which are difficult to stop without outside help (PAULUS, 2023; SCHIEPEK, 2020). In a psychotherapeutic setting, this temporal trend is summarized as a depression spiral (COYNE, 1986). [23]

The challenge in recording the temporal-dynamic development of psychosocial hazards lies in monitoring them subjectively over a longer period of time. Even time-sensitive labor science methods, such as the Düsseldorf model of the health circle3), offer regular and time-limited discussion groups on work-related stresses. Still, they only allow snapshots of the work sphere. Only regular monitoring of the dynamic interactions within everyday life can adequately depict the problem of the activity-impact relationships of the temporal-dynamic development of psychosocial hazards: The formation of social lifestyles is not based on a one-off stimulus-response mechanism of stress/strain. It must be characterized as activity-cause-effect relations: Intervening-operative activities change reality in the creation of living conditions in such a way that health-preserving or health-endangering lifestyles can arise (HOLZKAMP, 1983, p.166). Depending on the activity or ability to act, dynamic interdependencies of risk or health constellations arise over time. [24]

If the restrictive capacity to act can be understood as a coping behavior that is centered on getting through in everyday and critical life situations (SCHRÖER, 2013; see also BÖHNISCH & SCHRÖER, 2008), it is necessary to design an iterative, repetitive, and improvement-oriented process in accordance with the challenge of recording the temporal-dynamic development of psychosocial hazards over time. This process should make it possible to examine the temporal-dynamic development of the restrictive capacity to act, with the aim of designing a consciously precautionary disposition of social-individual living conditions. [25]

In conclusion: Current methodological challenges involve understanding how occupational and personal workloads are integrated into an individual's life situation and position. This includes examining how these workloads correspond to subjective perceptions and coping strategies, and how this understanding can be used to assess and change risk constellations over time. It requires a further development of analytical procedures in labor science towards subject-oriented and time-sensitive participation procedures. In the following section, these challenges are framed as a research program. [26]

3. Research Program of a Subject-Scientific Labor Research

The following outline of subject-scientific labor research is the consequence of the epistemological challenges outlined above. My framing is based on the criteria for research programs of LAKATOS (1974) and KLEINING (1982). I do not claim to postulate the subject-scientific program of labor science. Still, I am concerned with the interdisciplinary urgency of combining subject-scientific and labor-scientific approaches to overcome disciplinary epistemological hurdles. [27]

According to LAKATOS (1974), epistemological paradigms or theoretical theses can only be developed within the framework of broader systems and methodological rules, and should be organized as research programs. The latter are thus upstream of theories and contain rules for verification as to how an investigation can be structured and immunized against falsification. General elements of an epistemological research program are the methodological decisions (p.130), which are irrefutably defined in relation to the respective scientific premises. [28]

With reference to a research program of subject-scientific labor research, the following subsections must first clarify the research interest (Section 3.1). Furthermore, the basic assumptions and rough guidelines (Section 3.2) as well as research strategies (Section 3.3) must be determined in order to conceptualize social conditions regarding the interaction with the individual's respective ability to act. According to LAKATOS, the hard core of a research program requires additional assumptions that support the theoretical and methodological decisions. This is determined by positive and negative heuristics (Section 3.4), i.e., by guidelines on how research can be conducted (positive) or what should be avoided (negative). The heuristics include strategies for correcting and expanding refutable versions of a research program. These strategies aim to adapt and improve the program according to epistemological premises through the use of auxiliary hypotheses (Section 3.5) (p.131; see also KLEINING, 1982, 1995). With regard to the modeling of subject-scientific labor research, the relevant elements shall be derived in the following subsections on the basis of the criteria established by LAKATOS (1974). This serves to sharpen the program of subject-scientific labor research and to formulate methodological consequences (Section 3.6). [29]

In the context of subject-scientific labor research, an interest in knowledge lies in collaboration with all stakeholders. This entails:

Finding out what structural conditions exist, i.e., for both paid employment and unpaid care work;

Understanding the meaning individuals attach to their conditions, the opportunities for action these social conditions represent, and the extent to which employment and caregiving conditions enable or hinder their ability to act;

Determining which conditional and meaningful characteristics are particularly significant for the individuals, so that they can justify their actions in order to derive the respective psychosocial risk potentials and ensure the sustainable reproduction of work assets. [30]

The core of such a research program lies in understanding the conditions and burdens of gainful employment and care work, how people perceive/interpret them, and what reasons for action or restrictions arise from conditions and interpretations. [31]

When actions are justified by social conditions and their personal significance in line with individual interests (i.e., premise-reason contexts), the evaluation of restrictive reasons for action is similarly focused on how, why, and by what means these issues arise and how they can be resolved. Accordingly, the short- and long-term research strategy should be oriented towards the following points: [32]

In the short term, the aim of this subject-scientific labor research is to make statements together with all participants as to which conditions, meanings, and subject relationships justify restrictive and generalized agency. A further goal is to create the ability to evaluate restrictive options for action. In the long term, the aim is to work with subjects to expand restrictive capacities for action for the purpose of collective self-empowerment in order to develop alternative contexts of conditions, meanings, and justifications. [33]

I derived the research rules of subject-scientific labor research from qualitative heuristics (KLEINING, 1982, 1995). Accordingly, the research paths must be designed in such a way that the premises can be changed and further developed by the sample or by the subjects themselves. These principles are determined by positive and negative heuristics. Accordingly, it is important to exclude procedures that make participation in the research process impossible or to develop procedures that create it. The rules thus include the premises of the core of the research program:

Subjects are not researched but qualified as co-researchers by means of participatory, intervening research methods.

It is not the characteristics of subjects (e.g., depressive) that are researched. Instead, scrutiny lies on the respective conditions under which they suffer (e.g., exhausting time resources) as well as concepts that favor the exploitation of work assets. [34]

Auxiliary hypotheses are an element of heuristics as the "development and application of discovery procedures in a rule-guided form" (KLEINING, 1995, p.225). These support the gain in knowledge, which is inevitably connected to limited knowledge and incomplete information at the beginning. Auxiliary hypotheses are based on probable statements:

Strategies in the capitalist economy result in an extensification and intensification of workloads. This leads to health problems and encourages the (self-)exploitation of labor power.

Under the conditions and meanings of capitalistically organized gainful employment and care work, there are often only possibilities for action that are self-damaging (competition, exhaustion of labor resources, etc.). [35]

The subject-scientific approach is based on the assumption that a dialog between researcher and researched must be developed during the qualitative research process. If subjectivity is assumed, and the co-researcher principle is the goal, intersubjectivity necessarily follows. This in turn must be checked by quality criteria (such as reliability and validity) (KLEINING, 1995, pp.318ff.). The empirical question is not whether condition-meaning-justification relationships are falsifiable in the nomothetic sense. Rather, the inquiry focuses on whether explanations of reasons enable generalizations (HOLZKAMP, 1995b, pp.27ff.; MARKARD, 2020, p.171). In the context of subject-scientific labor research, the following questions are central:

How does the subject experience work conditions (of gainful employment and care work activities)?

How does the subject understand, represent, or interpret these conditions?

What subjective reasons for action can be derived from this? [36]

It should be added that generalized statements can provide insights into how the everyday lives of individuals in specific historical constellations may be described as a generalization of possibilities of structures that objectively restrict or enable action (HOLZKAMP, 1983, p.545). In Section 4, these methodological decisions and questions are deepened with regard to the modeling of subject-scientific labor research in order to derive the method. [37]

4. Model and Process of a Subject-Scientific Labor Research

The following model essentially describes a process and the possibility of understanding how and why people who live under similar social material conditions interpret them differently and behave subjectively towards them. The modeling is intended to provide a basis for methods when researchers and co-researchers work on their questions together by means of a "sequencing of the research process" (HOLZKAMP, 1990, p.9). Sequencing involves four steps:

Investigation of conditions: The recording of the problems of those affected, the overcoming of which is of existential interest on the one hand, but on the other hand cannot be achieved under the current conditions or with the available ways of thinking and acting.

Theorizing and expanding existing ways of thinking and acting: The scientific breakdown of their problems in collaboration with those affected. The research task is to develop meanings and alternative ways of thinking about figures of reasoning and practice in order to expand existing ways of thinking/acting.

Developing reasons for alternative courses of action: The justification of courses of action for a changed life practice, insofar as those affected want to adopt new perspectives for overcoming the problem/dilemma, and the abolition of old ways of thinking and practicing through the insight that they are no longer unintentionally acting against their own interests.

Iterative process for shaping a changed lifestyle: In a time-sensitive and repetitive process, attempting the shaping of a changed lifestyle in order to find out whether the initial problem can be overcome in the long term. The process should be repeated until the problem has changed. [38]

In terms of subject-scientific labor research, the following model would be structured as follows within the framework of a sequencing of the research process:

Fig. 3: Model of subject-scientific labor research (own illustration) [39]

This model of subject-scientific labor research includes the challenges derived above (see Section 2, Fig. 2). The concept of agency is central: Its characteristics and functional aspects are equivalent to an analytical determination and temporal framing (Steps 1-3). It becomes possible to examine class-specific disabilities in bourgeois society and the associated subjective levels of mediation, processing methods, and defense processes in individual development processes (HOLZKAMP, 1984a, p.9). By analyzing the lack of resources in the fourth step, or adding them, a social form of gaining life can emerge in which no longer merely existing natural resources are used individually or socially, but human living conditions are socially produced in communal, conscious, precautionary planning (HOLZKAMP, 1984b, p.18). In this context, resources mean individual capabilities (health, etc.), abilities (competence, compassion, etc.), social opportunities (supportive networks, etc.), material means (money, goods, income, living space, etc.), and immaterial means (education, social participation, recognition, etc.) that individuals can use to cope with everyday or specific work and life demands as well as psychosocial risks and ultimately to fulfill their own wishes. By having resources at their disposal, subjects are less at the mercy of life circumstances. Participation in social production, which mediates the individual reproduction of life, can be co-determined in an improved manner. This becomes clear in the context of everyday life, as different areas of life (gainful employment, family, friends, hobbies, etc.) sometimes contain contradictory demands. The temporal organization of everyday life as a coordination and negotiation effort with regard to individual options and the distribution of tasks and resources (HOLZKAMP, 1995a, p.822) is particularly challenging due to the limited nature of these material goods, care, and attention capacities. If these can be activated as aids for coping with developmental challenges, for the cyclical coping with everyday life (going to school, going to work or going home) or for critical life events, they have an important function in shaping the sustainable reproduction of working capacity. However, if they are limited or unavailable, self-damaging patterns of action can result. The better that resources can be activated, the more likely it is to compensate for restrictions on action and expand the scope for action. Resources therefore support coping strategies. They have a direct influence on maintaining health and quality of life. They can push back existential fears and make the everyday hardship of always having the same bearable (HOLZKAMP 1995a, p.845). For the consciousness-fulfilling breadth of actual life, further steps must be added in relation to the analysis of conditions and meanings. The focus is more on the function of cyclical life patterns, such as attending school or going to work, and understanding the reasons for continuously engaging in these repetitive structures. It also seeks to clarify to what extent these intentions and actions truly serve one's personal interests (p.843). Basically, this is the task for all steps, to work out specifically each time in what way the reduced and 'inverted' ways of thinking, crippled, isolated emotions that appear to each of us in bourgeois society as a private inner life, social relationships that appear as merely individual private relationships. Nevertheless, by taking into account the respective limited social conditions of development and their subjective processing by the individuals, we can understand them as special forms of expression of our orientation towards consciously disposing of our own living conditions, i.e., our ability to act (HOLZKAMP, 1984a, p.10). [40]

This model of subject-scientific labor research is based on the hypothesis that psychosocial risks stem from individual interactions, which can be dynamically represented in subjective models over extended periods of time (PAULUS, 2023). To this end, it is necessary to subjectively reconstruct the complex interdependencies over time. In this respect, the model includes a time-sensitive framework (see Section 2.3 in particular), which completes the sequencing described so far with the following methodological steps: [41]

Mental models are a basic concept for researching and changing complex dynamic problems in which human decisions play an essential role (FORRESTER, 1961). These represent an internal image, such as a hazard constellation, which is externally reflected in the actions and motivations of the actors involved. In order for them to change, space must be created for a discourse in which subjective meanings of risk constellations can be made explicit, discussed, explored and changed. These models can be individually appropriated and changed so that processes of empowerment are also promoted. [42]

4.2 Design of policies, measures and target agreements

When joint models are developed, researched and changed with several people on the basis of their subjective mental models, this can be described as the creation of policies, measures and target agreements or as a process of policy design (MEADOWS, 1999). Policy design processes start at different levels. They can therefore have different leverage effects. If, for example, individual modes of meaning or behavior or individual objectives are addressed, this corresponds to a change in individual parameters at a superordinate system level. From the Subjektstandpunkt [subject's point of view], these changes may have considerable consequences. Community processes in particular can be seen as important levers for promoting collective meanings and reasons for action and, in turn, for giving policy design processes a greater impact. [43]

4.3 Self-exploration through problem identification and updating

With a time-sensitive framework, the dynamic problems can be addressed. In a time-sensitive framework, the problems, i.e. descriptions of hazard constellations, are cyclically monitored and updated as they change. Such self-monitoring or assessment for learning (BLACK & WILIAM, 1998) serves to practice new measures (ways of meaning and acting) but also to validate the model (STERMAN, 2002) in order to reconstruct and understand complex dynamic hazard constellations. Assessment for learning is geared towards expansive learning (HOLZKAMP, 1995b, p.183). By means of self-exploration, those affected can recognize the causes of their situation. They may further comprehend how they can expand their ability to act in order to live a more self-determined life. However, this also means that the professional users (labor scientists, psychotherapists, coaches, members of companies and communities, etc.) must be aware of the interests of people affected by stress in order to be able to help shape learning processes in a participatory manner. Risk assessments from the point of view of those affected by stress are therefore not intrapsychic-cognitive activities. They are, instead, a specific form of social action in which the learning action develops as a learning loop, compared to the everyday action (p.188). In the following section, the methodology described is illustrated using research projects that have already been carried out. [44]

5. Methodology and Empiricism of the Model and Process of Subject-Scientific Labor Research

In several interdisciplinary research projects, the model of subject-scientific labor research was operationalized, developed, and implemented in different work contexts. The following section focuses specifically on the utilized methodology. In the projects on reconciliation problems (Section 5.1), the focus was on sequencing the research process (Section 4). Regarding the projects on work integration after exhaustion depression and on the SELBA formative risk assessment, a process and software to Selbst Arbeitsbelastungen und Arbeitsbeanspruchungen erkennen, verstehen, verändern und monitoren [I recognize, understand, change and monitor my own work stress and strains) (Section 5.2), the focus was also on time-sensitive implementation (Sections 4.1-4.3).4) [45]

In the reconciliation projects, software was developed for a simulator that allows employees, in consultation with their families and employers, to create tailored strategies. This is done by first recording their daily lives, including current life situations, sources of dissatisfaction, and desires for future models of employment and caregiving (explicit modeling). The results serve as a basis for decision-making and implementation aids for employees, families and employers in order to agree on appropriate measures (policy design). The compatibility parameters can be changed accordingly in the simulator. Alternative planning ideas can also be discussed and tried out with family members as well as contact persons in the company (self-exploration through problem identification and updating). An ideal-typical process was developed for the sake of the project as an implementation aid for these steps and presented in a video:

Fig. 4: Process for using the compatibility simulator. Please click here or on the image to start the video on YouTube (German language). [46]

The simulator is based on the sequencing of the research process described above: Employees must consult the compatibility simulator before an employee interview. In the first step, it is used to record the current situation (examination of the conditions: Time management, time required for gainful employment and care work, income levels, variations in the scope of care, social and personal resources, health, change in working model) and discovery of which working conditions trigger stress. In the second step, the subjective meanings attributed to the conditions are surveyed. If damaging patterns of action are identified, the question is asked how these should change. The focus is on individual meanings (wishes, conflicts, dissatisfaction, resources). The software reacts to the previous input so that, for example, the future work model can be adapted to specific life situations. After creating such a compatibility plan as an extension of existing ways of thinking and acting, it is possible to enter into an exchange with relatives. In the third step, the individual opportunities and (existing or missing) resources for shaping their own life situation can be recognized and ideas for improvement developed, i.e., alternative courses of action can be justified. If the family members agree to the chosen work-life-balance model, the alternative lifestyle concept can be negotiated with superiors in a fourth step. The compatibility simulator is designed to enable expansive learning. This is achieved by allowing users to determine the relationship between themselves and their environment. Users may further establish this relationship on the basis of their own interests and reasons for learning and implementing their acquired knowledge. As the compatibility simulator is used periodically in an iterative process, and results can be accessed, users may create a learning loop. Those involved can recognize how life situations change. Furthermore, it becomes possible to understand which measures work to shape a changed lifestyle. [47]

In summary, it can be said that the work-life balance simulator creates additional options for employees: Previously individually available meanings for understanding a work-life balance situation experienced as problematic are expanded by alternative options for action. They experience a shift from the knowledge they previously had and learn to navigate operational or socially available contexts of meaning. Ideally, this enables them to achieve personal self-determination, better manage their own living conditions, and actively participate in social development. However, there is a risk that justifications can be produced defensively, i.e., on the basis of other people's interests, e.g., to avoid conflicts: To address the legitimate defense of one's own lifestyle and ultimately act in the interest of others, the reconciliation process was designed to foster mutual understanding between participants regarding their respective personal goals. [48]

5.2 SELBA (Selbst Arbeitsbelastungen und Arbeitsbeanspruchungen erkennen, verstehen, verändern und monitoren) [I recognize, understand, change and monitor my own work stress and strains])

In these projects, a formative process and an app were developed for burnout patients in order to explore health-threatening interactions between workloads, stresses, and coping strategies in the course of reintegration after a hospital stay, as part of self-monitoring. The individually configurable app allows users to create scenarios based on the information they enter regarding their life situation. They can set goals that are based not only on behavioral but also on relational prevention. Further, they may determine the resources they require in order to achieve a specific scenario. At an individually defined interval, they compare actual as well as target values and repeat the self-monitoring process. The implementation (1. explicit modeling, 2. policy design, 3. self-exploration and updating of risk constellations) is presented below. [49]

5.2.1 Step 1: Explicit modeling

The explicit modeling of one's own risk constellations takes place on the basis of objective stressors, subjective meanings, functional and dysfunctional coping strategies, as well as resources (see the tools in Fig. 5). This step serves to examine conditions and expand existing ways of thinking and acting. It is substantially oriented towards the condition-meaning-justification analysis (MARKARD, 2000). The software contains a free area for recording. Users can utilize it to relate elements that are important to them by positioning them spatially and to visualize a premise situation. A list is available for selecting stressors, meanings, coping strategies, and resources (for a detailed description, see PAULUS et al., 2023; RABENSTEINER et al., 2023).

Fig. 5: Exemplary explanatory model (screenshot software) [50]

The modeling of the explanatory model takes place in dialog with confidants (peers, coaches, psychotherapists, social workers, etc.). One aim is to identify negative interpretations and dysfunctional coping strategies (elements with a minus sign) with the help of confidants. A further goal is to develop alternative conditions, meanings, and possible courses of action (elements with a plus sign) in order to improve life and work situations. The conditions of the elements in red brackets in Fig. 5 are the most urgent to change. [51]

As part of the policy design, the timing and content of alternative courses of action as well as the iterative process for shaping a changed lifestyle through self-exploration are defined. Plans and strategies for changing risk constellations are developed and implemented in dialog with trusted individuals. Users are asked questions at regular intervals about the selected elements of the explanatory models (in red brackets in Fig. 5). Based on the knowledge gained from the explicit modelling, alternative strategies or justifications for alternative courses of action are derived in order to improve everyday life by organizing measures over time. [52]

5.2.3 Step 3: (Self-)Research and updating the risk constellation

Between sessions with confidants, users can monitor time series data on workloads and stresses, coping strategies, resources, individual life goals, personalized risk constellations, early warning indicators, and health-preserving/promoting factors on the basis of their respective activity-cause-effect relationships. These appear as progression diagrams on the personalized dashboard, using a visualized traffic light system.

Fig. 6: Time series (observations on current personal early warning signs and the current risk constellation) [53]

In the context of self-exploration, the users arrange the time series in such a way that they can recognize correlations. In this way, hypotheses on self-reinforcing (health-promoting or health-damaging) as well as self-regulating dynamics can be developed, rejected or confirmed. Tipping points and the associated patterns can be identified (e.g., in Fig. 6, a connection between a large amount of work, high alcohol consumption, low well-being and sleep can be recognized). A problem update might be operationalized in the software, e.g., in the context of psychotherapy or by users themselves, by creating or adapting explanatory models or changing the observed elements. [54]

In summary, it can be said that the time-sensitive steps serve to enable users to create personalized risk and health-preserving/promoting scenarios on the basis of their own modeling. These in turn allow them to achieve a prospective orientation of their everyday lifestyle and to look beyond the immediate management of everyday life. They can therefore observe themselves in everyday life over a longer time period (several weeks, months to years). Additionally, they are capable of anticipating risks at an early stage by recognizing certain constellations. [55]

The aspects of subject-scientific labor research discussed here, aimed at identifying limitations in the capacity to act and developing measures to expand it, have primarily focused on methodological considerations. In this way, only an indirect contribution is made to achieving a generalized capacity to act; the focus is on individual rather than societal potential for change in problems of everyday life. Nevertheless, the focus on recording individual capacity to act allows specific situations to be analyzed in terms of whether and in what way the respective coping strategies make it possible to overcome conditions that stand in the way of change. This is also important for the attitude of researchers, peers, coaches, psychotherapists, social workers, etc. Thus, people who suffer from exhausted resources, are unemployed, etc., are not additionally portrayed as victims incapable of acting. This unintentionally adds another facet to their public labeling as useless and unfit (HOLZKAMP, 1986, pp.19f.) or as those who have to change social conditions, which thus objectively worsens their situation (ibid., see also KNEBEL, 2013). Of course, the question remains as to whether a generalized capacity to act can be achieved at all under capitalist conditions. Accordingly, researchers are faced with the challenge of not developing a methodological institutionalism that would lead to the creation of an institutionalized life course against the background of the reproduction of labor power as a naturalized maxim of orientation! (SCHROER, 2013, p.64). Instead, the aim is to support individual coping challenges in a subject-oriented manner with the aim of expanding the ability to act. With this orientation, the focus is not on people's shortcomings but on the conditions, meanings, and justifications under which they suffer. Consequently, social conditions must be understood as constellations of conditions, meanings and justifications—i.e., as possibilities for action for individuals—including the contradictions and limitations therein (HOLZKAMP, 1986, p.23). The connection between individual motivations and social structures is influenced by the epistemic status of subjective perception and the meanings that individuals attach to it. As a result, future practices for shaping everyday life can be embedded in distinct contexts of action and order, which are separated from one another. In this way, subjectivity can be clarified. Reasons for action in the sense of subject viewpoints may be justified. The most elementary challenge of an approach to supporting everyday life as a self-reproductive system is to ensure that the functionality of actions or intentions to act do not contradict the actor's interest in life (HOLZKAMP, 1995a, p.842). Ideally, the interaction within a research project is not based on cost-benefit considerations or the instrumentalization of others. It should be founded on the principle of mutual improvement of one's own life possibilities—under "common and generalizable perspectives for action and development" (HOLZKAMP, 1987, p.55). With such an approach, the danger of diagnostic, epistemic or unspoken inductivism can be viewed critically. This can lead to dependencies on researchers, experts, social workers, educators, helpers, etc. Those affected cannot develop the ability to help themselves (HABERMAS, 1971). Instead, they may reflect on their own points of view. Thus, they become capable to change the structure of an outdated dispositive of the functionalization of individuals and the institutionalization of life courses. [56]

As stress develops dynamically and is experienced as well as processed transactionally, the challenges in preventing work stress continue to lie in identifying and subjectively assessing changes in individual experiences over time and changing conditions or working relationships. According to current research, the framework conditions in occupational health and safety are not yet geared towards these challenges; measures often depend on quantifiable measured values or DIN standards and procedures (PAULUS, 2018b, 2022). Consequently, it can be assumed that the potential with regard to the prevention of stress-related workloads is not yet being fully exploited. This not only makes an appropriate analysis of stress prevention more difficult. It also raises the question of how effective interventions are when a subject-oriented and time-sensitive potential is realized in practice. With regard to the transferability of the subject-scientific perspective to other areas of occupational safety and health, the elements and procedures described can be used to address and work on the research challenges in the area of occupational safety and health (BDP, 2023; WALTERS, WADSWORTH, HASLE, REFSLUND & RAMIOUL, 2018). To this end, labor science instruments and processes must be adapted to the specific setting in order to take into account the interests of the actors or groups of actors involved: Elements of subjective explanatory models and problem actualization in practical implementation must not be aimed at behavioral prevention, i.e., that employees should become more efficient, more resilient, etc. Instead, working conditions and living conditions must be taken into account. [57]

1) Care work includes, among other things, self-care, unpaid housework, caring for children, relatives or friends. <back>

2) All translations from non-English texts are mine. <back>

3) The health circle is an instrument of workplace health management. The aim of health circles, which can be set up at the same hierarchical level (Berlin model) or across hierarchies (Düsseldorf model), is to use the experiential knowledge of employees to analyze health hazards in the workplace and develop solutions (DEPLAZES & KÜNZLI, 2010). <back>

4) The work-life balance simulator was developed in the Our Company project (2016-2017) in cooperation with Thomann Nutzfahrzeuge AG, Sonderschule Bad Sonder and Abraxas Informatik AG, among others. The project was then further developed into the Life Balance Check (2019-2021) in collaboration with the UND specialist unit, which licensed it and offered it in consultations throughout Switzerland. Both projects were supported by the Federal Office for Gender Equality (FOGE), with funding under the Gender Equality Act. The results of the formative risk assessment are based on the basic research project Psychosocial Risks in the World of Work [10001A_178934] (2018-2022), which was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, and the Innosuisse research project SELBA [53268.1 IP-LS] (2021-2023). These projects were developed in collaboration with individuals affected by burnout as well as doctors, psychologists, and psychotherapists from the Gais Clinic, Switzerland and Opinion Games (SELBA). All projects were the result of interdisciplinary collaboration between employees of the Institutes of Social Work and Modeling and Simulation at the University of Applied Sciences of Eastern Switzerland, St. Gallen, namely Vanessa TOSCAN, Jasmin RABENSTEINER, Thomas SCHMID, Fabian LEUTHOLD, Myriel RAVAGLI, Adrian STÄMPFLI, and Alexander SCHEIDEGGER. They were comprehensively documented (EBG, SNF), and the impact of SELBA was evaluated by RABENSTEINER, TOSCAN, THIEL, PAULUS & SCHEIDEGGER (2023). <back>

Alinsky, Saul (2010). Call me a radical. Organizing und empowerment. Göttingen: Lamuv Verlag.

Anhorn, Roland (2012). Wie alles anfing ... und kein Ende findet. Traditionelle und kritische Soziale Arbeit im Vergleich von Mary E. Richmond und Jane Addams. In Roland Anhorn, Frank Bettinger, Cornelis Horlacher & Kerstin Rathgeb (Eds.), Kritik in der Sozialen Arbeit – kritische Soziale Arbeit (pp.225-270). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Arciprete, Simeon (2015). Die Handlungsfähigkeit der Adressat*innen. Überlegungen zum Begriff des Subjekts im Dialog zwischen Sozialer Arbeit und Kritischer Psychologie. Widersprüche, 35(136), 117-128.

BAuA (Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin) (Ed.) (2014). Gefährdungsbeurteilung psychischer Belastung. Erfahrungen und Empfehlungen. Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag.

BDP (Berufsverband Deutscher Psychologinnen und Psychologen e.V.) (2023). BDP fordert Umsetzung gesetzlich vorgegebener Gefährdungsbeurteilung psychischer Belastung, https://www.bdp-verband.de/fileadmin/user_upload/DK-Resolution_Gefaehrdungsbeurteilung_Psyche.pdf [Accessed: July 9, 2024].

Beck, David & Lenhardt, Uwe (2009). Verbreitung der Gefährdungsbeurteilung in Deutschland. Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung, 4(71), 71-76.

Beck, David; Richter, Gabriele; Ertel, Michael & Morschhäuser, Martina (2012). Gefährdungsbeurteilung bei psychischen Belastungen in Deutschland. Verbreitung, hemmende und fördernde Bedingungen. Prävention und Gesundheitsförderung, 7(2), 115-119.

Beck, Ulrich & Beck-Gernsheim, Elisabeth (2011). Fernliebe. Lebensformen im globalen Zeitalter. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Bergold, Jarg & Thomas, Stefan (Eds.) (2012). Participatory qualitative research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/issue/view/39 [Accessed: September 9, 2024].

Black, Paul & Wiliam, Dylan (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in education: Principles. Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7-74.

Böhle, Fritz (2010). Arbeit und Belastung. In Fritz Böhle & Anna Hoffmann (Eds.), Handbuch Arbeitssoziologie (pp.451-481). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Böhle, Fritz & Senghaas-Knobloch, Eva (Eds.) (2020). Andere Sichtweisen auf Subjektivität. Impulse für kritische Arbeitsforschung. Heidelberg: Springer VS.

Böhnisch, Lothar & Schröer, Wolfgang (2008). Entgrenzung, Bewältigung und agency – am Beispiel des Strukturwandels der Jugendphase. In Günther Homfeldt, Wolfgang Schröer & Cornelia Schweppe (Eds.), Vom Adressaten zum Akteur. Soziale Arbeit und Agency (pp.47-58). Opladen: Budrich.

Coyne, James C. (1986). Essential papers on depression. New York, NY: New York University Press

Deplazes, Silvia & Künzli, Hansjörg (2010). Arbeit und Gesundheit – Betriebliches Gesundheitsmanagement. In Birgit Werkmann-Karcher & Jack Rietiker (Eds.), Angewandte Psychologie für das Human Resource Management (pp.435-448). Berlin: Springer

Eichinger, Ulrike & Weber, Klaus (2012). Soziale Arbeit. Hamburg: Argument.

Engels, Friedrich (1952 [1845]). Die Lage der Arbeitenden Klasse in England. Nach eigner Anschauung und authentischen Quellen. Berlin: Dietz.

Forrester, Jay W. (1961). Industrial dynamics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Foucault, Michel (1977 [1975]). Überwachen und Strafen. Die Geburt des Gefängnisses. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Frosch, Alfred; Martiny, Ulrike & Paulus, Stefan (2014). Sozialwissenschaftliche Auswertung subjektiver Wahrnehmungen von Straßenreinigern und Müllwerkern über ihre Arbeit. In Institut für Arbeit und Technik (IFAT) (Ed.), Arbeitswissenschaftliche Untersuchung der Entsorger bei Hausmüllabfuhr und Straßenreinigung Hamburg (pp.113-180). Hamburg: IFAT.

Gottschall, Karin & Voss, G. Günter (2003). Zur Einleitung. In Karin Gottschall & G. Günter Voss Hrsg.), Entgrenzung von Arbeit und Leben. Zum Wandel der Beziehung von Erwerbstätigkeit und Privatsphäre im Alltag (pp.11-31). München: Rainer Hampp Verlag.

Graßhoff, Gunther (2015). Adressatinnen und Adressaten der Sozialen Arbeit. Eine Einführung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Graßhoff, Gunther (2018). Partizipative Sozialforschung. In Gunther Graßhoff, Anna Renker & Schröer, Wolfgang (Eds.), Soziale Arbeit. Eine elementare Einführung (pp.673-686). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Graßhoff, Gunther; Renker, Anna & Schröer, Wolfgang (Eds.) (2018). Soziale Arbeit. Eine elementare Einführung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Groskurth, Peter & Volpert, Walter (1975). Lohnarbeitspsychologie. Berufliche Sozialisation: Emanzipation zur Anpassung. Frankfurt/M.: Fischer.

Habermas, Jürgen (1971). Theorie und Praxis. Einige Schwierigkeiten beim Versuch, Theorie und Praxis zu vermitteln. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Hägele, Helmut unter Mitarbeit von Engels, Dietrich & Fertig, Michael (2019). Arbeitsschutz auf dem Prüfstand. Abschlussbericht zur Dachevaluation der Gemeinsamen Deutschen Arbeitsschutzstrategie, https://www.gda-portal.de/DE/Downloads/pdf/GDA-Dachevaluation-2019-Abschlussbericht.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=1 [Accessed: August 29, 2024].

Hahnzog, Simon (2015). Psychische Gefährdungsbeurteilung. Impulse für den Mittelstand. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

Haug, Frigga (2003). Schaffen wir einen neuen Menschentypus. Das Argument, 252, 606-617.

Hirschfeld, Uwe (2012). Vom Nutzen der Hilfe und der Hilfe des Widerstands – Widersprüche Sozialer Arbeit. In Ulrike Eichinger & Klaus Weber (Eds.), Soziale Arbeit (pp.264-280). Hamburg: Argument.

Holzkamp, Klaus (1973). Sinnliche Erkenntnis. Historischer Ursprung und gesellschaftliche Funktion der Wahrnehmung. Frankfurt/M.: Athenäum.

Holzkamp, Klaus (1983). Grundlegung der Psychologie. Frankfurt/M.: Campus.

Holzkamp, Klaus (1984a). Zum Verhältnis zwischen gesamtgesellschaftlichem Prozess und individuellem Lebensprozess. Konsequent, 6, 29-40, https://www.kritische-psychologie.de/files/kh1984a.pdf [Accessed: August 29, 2024].

Holzkamp, Klaus (1984b). Kritische Psychologie und phänomenologische Psychologie. Der Weg der Kritischen Psychologie zur Subjektwissenschaft. Forum Kritische Psychologie, 14, 5-55, http://www.kritische-psychologie.de/files/FKP_14_Klaus_Holzkamp.pdf [Accessed: August 29, 2024].

Holzkamp, Klaus (1985). Grundkonzepte der Kritischen Psychologie. In Diesterweg-Hochschule (Ed.), Gestaltpädagogik – Fortschritt oder Sackgasse (pp.31-38). Berlin: Verlag Schulze Soltau, https://www.kritische-psychologie.de/files/kh1985a.pdf [Accessed: August 29, 2024].

Holzkamp, Klaus (1986). "Wirkung" oder Erfahrung der Arbeitslosigkeit – Widersprüche und Perspektiven psychologischer Arbeitslosenforschung. Forum Kritische Psychologie, 18, 9-37, https://www.kritische-psychologie.de/files/FKP_18_Klaus_Holzkamp.pdf [Accessed: August 29, 2024].

Holzkamp, Klaus (1987). Die Verkennung von Handlungsbegründungen als empirische Zusammenhangsannahmen in sozialpsychologischen Theorien: Methodologische Fehlorientierung infolge von Begriffsverwirrung. Forum Kritische Psychologie, 19, https://www.kritische-psychologie.de/files/FKP_19_Klaus_Holzkamp.pdf [Accessed: September 10, 2024].

Holzkamp, Klaus (1990). Über den Widerspruch zwischen Förderung individueller Subjektivität als Forschungsziel und Fremdkontrolle als Forschungsparadigma. Forum Kritische Psychologie, 26, 6-12, https://www.kritische-psychologie.de/1990/ueber-den-widerspruch [Accessed: August 29, 2024].

Holzkamp, Klaus (1995a). Alltägliche Lebensführung als subjektwissenschaftliches Grundkonzept. Das Argument, 212, 817-846, https://www.kritische-psychologie.de/files/AS_212_Klaus_Holzkamp_Lebensf%C3%BChrung.pdf [Accessed: August 29, 2024].

Holzkamp, Klaus (1995b). Lernen. Subjektwissenschaftliche Grundlegung. Frankfurt/M.: Campus.

Holzkamp, Klaus (1997). Gesellschaftliche Widersprüche und individuelle Handlungsfähigkeit am Beispiel der Sozialarbeit. In Klaus Holzkamp, Schriften 1. Normierung, Ausgrenzung, Widerstand (pp.385-403). Hamburg: Argument.

Hovmand, Peter S. (2014). Community based system dynamics. New York, NY: Springer.

Janetzke, Hanna & Ertel, Michael (2016). Gefährdungsbeurteilung psychosozialer Belastungen im europäischen Vergleich. Forschungsförderung Working Paper, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, https://www.boeckler.de/de/faust-detail.htm?sync_id=HBS-006377 [Accessed: August 29, 2024].

Jürgens, Kerstin (2003). Zeithandeln – eine neue Kategorie der Arbeitssoziologie. In Karin Gottschall & G. Günter Voss, (Eds.), Entgrenzung von Arbeit und Leben. Zum Wandel der Beziehung von Erwerbstätigkeit und Privatsphäre im Alltag (pp.37-58). München: Rainer Hampp.

Jürgens, Kerstin (2006). Arbeits- und Lebenskraft. Reproduktion als eigensinnige Grenzziehung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Jürgens, Kerstin (2022). Reproduktion von Arbeitskraft. In Hartmut Hirsch-Kreinsen, Heiner Minssen, Sabine Pfeiffer & Mascha Will-Zocholl (Eds.), Lexikon der Arbeits- und Industriesoziologie (pp.326-330). Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Jürgens, Kerstin; Hoffmann, Reiner & Schildmann, Christina (2017). Arbeit transformieren! Denkanstöße der Kommission "Arbeit der Zukunft". Bielefeld: transcript.

Kleining, Gerhard (1982). Umriss zu einer Methodologie qualitativer Sozialforschung. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 342, 224-253, https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-8619 [Accessed: August 29, 2024].

Kleining, Gerhard (1995). Lehrbuch Entdeckende Sozialforschung. Vol. I. Von der Hermeneutik zur qualitativen Heuristik. Weinheim: Beltz.

Knebel, Leonie (2013). Anstieg "depressiver Störungen" im neoliberalen Kapitalismus? Kritisch-psychologische Anmerkungen zu Methode und Ergebnissen der Depressionsforschung. Forum Gemeindepsychologie, 18, 1-13, https://www.academia.edu/4866561/Anstieg_depressiver_St%C3%B6rungen_im_neoliberalen_Kapitalismus_Kritisch_psychologische_Anmerkungen_zu_Methode_und_Ergebnissen_der_Depressionsforschung [Accessed: August 29, 2024].

Köngeter, Stefan & Schröer, Wolfgang (2013). Variations of social pedagogy—Explorations of the transnational settlement movement. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 21(42), https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v21n42.2013 [Accessed: August 29, 2024].

Lakatos, Imre (1974). Falsifikation und die Methodologie wissenschaftlicher Forschungsprogramme. In Imre Lakatos & Alan Musgrave (Eds.), Kritik und Erkenntnisfortschritt. Abhandlungen des Internationalen Kolloquiums über die Philosophie der Wissenschaft. (pp.89-189). Wiesbaden: Vieweg+Teubner.

Lazarus, Richard S. (1999). Stress and emotion. A new synthesis. London: Free Association Books.

Lewin, Kurt (1948). Tat-Forschung und Minderheitenprobleme. In Kurt Lewin (Ed.), Die Lösung sozialer Konflikte (pp.278-298). Bad-Neuheim: Christian-Verlag.

Markard, Morus (1993). Methodik subjektwissenschaftlicher Forschung. Hamburg: Argument.

Markard, Morus (2000). Kritische Psychologie: Methodik vom Standpunkt des Subjekts. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2), Art. 19, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.2.1088 [Accessed: September 2, 2024].

Markard, Morus (2020). Kritische Psychologie. In Günter Mey & Katja Mruck (Eds.), Handbuch Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie (Vol. 1, pp.163-183). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Marx, Karl (1938). A workers' inquiry. New International, 12, 379-381, https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/ni/vol04/no12/marx.htm [Accessed: September 2, 2024].

Marx, Karl (1975 [1867]). Das Kapital – Kritik der politischen Ökonomie. Berlin: Dietz.

Maschewsky, Werner (1983). Ein integriertes Belastungskonzept – Methoden seiner Realisierung. Forum Kritische Psychologie, 12, 123-145, https://www.kritische-psychologie.de/files/FKP_12_Werner_Maschewsky.pdf [Accessed: September 2, 2024].

Meadows, Donella (1999). Leverage points: Places to intervene in a system. Hartland: The Sustainability Institute, https://www.donellameadows.org/wp-content/userfiles/Leverage_Points.pdf [Accessed: September 2, 2024].

Metz, Anna Marie & Rothe, Heinz-Jürgen (2017). Screening psychischer Arbeitsbelastung. Ein Verfahren zur Gefährdungsbeurteilung. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Ohm, Christof & van Treeck, Werner (1990). Die "kognitive Wende" in der Technikentwicklung als Herausforderung an die kritische Arbeitspsychologie. Thesen zu "Intelligenten Tutoriellen Systemen". Forum Kritische Psychologie, 25, 81-96, https://www.kritische-psychologie.de/1990/die-kognitive-wende-in-der-technikentwicklung-als-herausforderung-an-die-kritische-arbeitspsychologie [Accessed:. September 2., 2024].

Paulus, Stefan (2012). Das Geschlechterregime. Eine intersektionale Dispositivanalyse von Work-Life-Balance-Maßnahmen. Bielefeld: transcript.

Paulus, Stefan (2015). Methodologische Überlegungen und methodisches Vorgehen bei einer intersektionalen Dispositivanalyse. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 16(1), Art. 21, https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-16.1.2103 [Accessed: August 29, 2024].

Paulus, Stefan (2016). Psychische Arbeitsbelastungen und betriebliches Gesundheitsmanagement. Handlungsbedarf in der Sozialen Arbeit. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Soziale Arbeit, 18, 73-92, https://szsa.ch/ojs/index.php/szsa-rsts/article/view/145 [Accessed: August 29, 2024].

Paulus, Stefan (2017). Betriebliche Einschließungsmilieus. Formen des gegenseitigen Überwachens. In Utta Isop (Ed.), Gewalt im beruflichen Alltag – Wie Hierarchien, Einschlüsse und Ausschlüsse wirken! (pp.41-48). Neu-Ulm: AG Spak.

Paulus, Stefan (2018a). Mit dem Vereinbarkeitssimulator zur Work-Life-Balance. Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven und Lösungsansätze. In Sebastian Wörwag & Alexandra Cloots (Eds.), Zukunft der Arbeit. Perspektive Mensch (pp.149-164). Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.