Volume 6, No. 1, Art. 46 – January 2005

Secondary Analysis of Interviews: Using Codes and Theoretical Concepts From the Primary Study1)

Irena Medjedović & Andreas Witzel

Abstract: In spite of the possibilities which secondary analysis of qualitative data offers, this method is not often used because of the critical attitude towards a lot of methodological and ethical problems, and also on the grounds of the inadequate access to, and preparation of, the primary data in Germany. It is our opinion that the prevailing scepticism towards secondary analysis is also connected with a lack of practical experience.

Based on the example of biographical interview data compiled by a longitudinal study of the biographical shaping of the school-to-work transition of young adults, we would like to show the possibilities which exist for making use of pre-existing data under specific methodological conditions.

The demand for data for secondary analysis is usually limited to the original data from the primary study. In our experience, though, it is also possible to use the coding and category schemas of the computer-assisted evaluation process of the primary study. Furthermore, with the inclusion of theoretical concepts of the primary study such as typologies it is even possible to use an inductive procedure. For example, provided that category schemas have the same heuristic function as a huge "filing box" with broad, and not "a priori" theory-loaded categories, then their use for secondary analysis does not have to conflict with open coding in the process of the development of in-vivo categories.

Key words: secondary analysis, interview, computerised evaluation process, panel data, coding, category schema, theoretical concept, typology

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Reasons for, and Research Questions of, the Secondary Analysis

3. The Investigative Approach of the Primary Research Project: A1 "Status Passages into Gainful Employment"

4. The Suitability of the Data for the Purpose of the Secondary Analysis

5. The Use of the Coding of the Primary Study

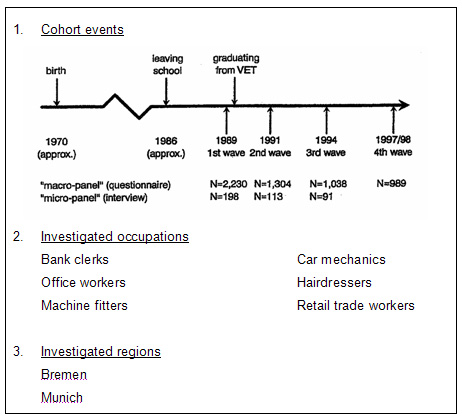

6. The Use of the Theoretical Concepts of the Primary Study

7. Central Results of the Secondary Analysis

8. Conclusion

The numerous possibilities and opportunities for secondary analysis in the social sciences have a longer tradition in the field of quantitative methods (cf. for example KLINGEMANN & MOCHMANN, 1975; MOCHMANN, 1968) than in the scientific community of social researchers using qualitative methods, who have repeatedly expressed their reservations and scepticism. This assessment is confirmed by recent data (cf. OPITZ & MAUER in this FQS issue), which show that even the few users (of primary analysis material for secondary analytical purposes) in Germany often had problems with the execution of qualitative secondary analysis, namely lack of knowledge of the research context, and insufficient preparation and incompleteness of the data. We can also note the rather seldom use of secondary analysis, so that it is possible to say that the situation in Germany differs from that in Great Britain somewhat less than previously believed, where there has been a comparatively broad application of qualitative methods. THOMPSON (2000, p.3), for instance, talks of a "silent space" with regard to the execution of secondary analysis and methodological guidelines (with the use of qualitative handbooks) for the re-use of qualitative data produced by other researchers. [1]

In order to counter the described scepticism, which also seems to be based on a lack of methodological experience with qualitative secondary analysis, we feel the need—similarly to other authors in this edition—to show the feasibility and usefulness of secondary analysis using a concrete example from our own research. This deals with a secondary investigation into a specific, thematically defined question based on our own primary data.2) [2]

2. Reasons for, and Research Questions of, the Secondary Analysis

The starting point for our secondary analysis is possibly quite typical: the results, often the publications of a research project, are taken note of by the scientific community and discussed from the point of view of their own theoretical stance or empirical data. Conferences are then organised on thematically relevant subjects and the organisers, or the invited projects, subsequently develop ideas for a combination of new projects under a common research topic. For instance, in view of our extensive investigations into the shaping of the occupational biography of young skilled workers, the A1-project "Status Passages into gainful Employment" of Collaborative Research Centre 186 (Sonderforschungsbereich 186/Sfb 186)3) was asked to make a contribution to a conference on new concepts for the knowledge acquisition of skilled workers4). With a view to possibly preparing a subsequent contribution for a book, it seemed worthwhile to check the project data for possibly new, empirical findings on the theme "work-process knowledge". Therefore the authors decided to make a secondary analysis contribution (HEINZ, KÜHN & WITZEL, 2005) based on the above-mentioned project data for a book (FISCHER, BOREHAM & NYHAN, 2004)5) about the state of European research on the theoretical concept of work-process knowledge. [3]

The concept of "work-process knowledge"

The starting point for current considerations on, and empirical investigations into, the topic of work-process knowledge was the question as to whether globalisation and its consequent demands for competition have created new forms of work, forms which are characterised by an increase in the intensity of knowledge. The research interest focussed on those forms of knowledge that are not limited to skills associated with the Tayloristic execution of work, but are rather in a broader sense connected to the whole process of work. Employers are interested in such forms of knowledge, because they anticipate an improvement in skills and a more flexible application of working practices. [4]

Work-process knowledge is defined as "a form of knowledge, which guides practical work" (RAUNER, 2002, p.25). It consists on the one hand of practical or active knowledge, and on the other hand of knowledge of a theoretical or scientific nature. The integrated form, or the interface of the two forms of knowledge is posited as the knowledge typical of a skilled worker in any particular trade (see FISCHER, 2005). A central question is how these forms of knowledge are acquired through understanding and executing the working process as a whole. A dialectical learning process of solving the problem of the contradictions between the forms of knowledge is assumed, for example, on the one hand between basic academic knowledge learnt at school, or knowledge from written instructions, and, on the other hand, direct experience based on operating a machine, for instance, or knowledge of skills and habits common to the work in question. [5]

Research questions of the secondary analysis

The idea for the execution of our secondary analysis came from the basic supposition that learning for work reasons is not only to be understood as the acquisition of concrete academic or vocational skills, but is also dependent on the occupational-biographical process of developing individual work expectations and career objectives in interaction with the opportunities and limitations of career paths. Previous findings regarding work-process knowledge tend to neglect this aspect. [6]

The primary study was suitable for filling this knowledge gap, because it dealt with the transition into gainful employment from the biographical performance point of view. Individual biographical orientation-, decision-, and action-processes in various entries into work, and in the light of changing social requirements, were investigated, including their consequences for the further shaping of the occupational biography. They were also at the same time regarded as the result of processing school and work experience, as well as of the result of decisions made, i.e. they were seen as the consequences of self-socialisation processes in which biographical aims, interests and motivations related to learning and to work were developed and modified. We were working on the assumption that life-course experiences not only influence the acquisition of work-process knowledge, but that work-process knowledge is itself embedded in a process of career-process knowledge. We found the first empirical indications to substantiate this thesis in a preliminary check of the primary data. [7]

As a consequence, two questions emerged for the secondary analysis:

How do the skilled workers acquire their work-process knowledge?

What role does biographical context play in work-process knowledge [8]

Methodologically, the objective of the secondary analysis involved evaluating pre-existing data from a new perspective, in order to investigate or examine a concept which was not central to the original research work.6) [9]

In the following, the primary study is briefly described in order to analyse its suitability for secondary analysis. [10]

3. The Investigative Approach of the Primary Research Project: A1 "Status Passages into Gainful Employment"

From the beginning, the project had tried to address its analytical questions with quantitative and qualitative data and procedures. Because of this, two sub-studies were carried out, both as prospective longitudinal studies. However, given the theme of this paper, more weight will be placed on the qualitative part of the investigation. [11]

The following central questions were to be answered using a combination of qualitative and quantitative procedures (cf. HEINZ, 1996): on the one hand, the structure of occupational risks and opportunities in two regional vocational training and labour markets, patterns of processes and transitions into vocational training and gainful employment, and also the initial years of gainful employment. And on the other hand, behaviour within structures, i.e.—more in line with fundamental research—the action strategies of young adults in their realisation of status passages into gainful employment and the processing of career plans and the results of actions. [12]

Given the central questions, the panel approach was chosen as the investigation design: see Fig. 1 (cf. MOENNICH & WITZEL, 1994; HEINZ et al., 1998). The samples contained a combination of different criteria such as labour market opportunities, the commonest apprentice-based occupations, and gender ratios. Members of six apprentice-based occupations (in Germany) were investigated—car mechanics, machine fitters, hairdressers, as well as bank, office, and retail trade workers—all of whom had completed their vocational training in the labour market regions of Bremen and Munich in 1989/90.

Figure 1: Design of the project "Status Passages into Gainful Employment" [13]

The quantitative investigation part (macro-panel) consisted of four questionnaires: from the first wave 1989 with approx. 2,200 people sampled, to the fourth wave 1997/8 with 989 participants. In the qualitative investigation part (micro-panel) three waves were set up (1989, 1991/2 and 1994, with 91 interviews spread over all three waves), using "problem-centred interviews" (WITZEL, 1982, 1996, 2000). [14]

The standardised questionnaires primarily served the collection of social-demographic information and information on the development of jobs and professional careers from completely different viewpoints. With data on careers, for instance, questions on job continuity from the point of view of time spent in that career could be examined. There was an examination as to what extent continuous permanent employment can be taken as the norm, and which forms and examples of interruption, e.g. unemployment or starting a family, could be observed. Furthermore, patterns of development over the whole eight-year period were identified (SCHAEPER, KÜHN & WITZEL, 2000; MOWITZ-LAMBERT, HEINZ & WITZEL, 2001). With the fourth wave, the data collection was extended to include work-, occupational-, further education-, gender role-, and family orientation (cf. SCHAEPER & WITZEL, 2001). [15]

The qualitative interviews focused on the internal perspective of the participants: on their expectations, and efforts to realise and evaluate them within the framework of their eight-year occupational biography. In this qualitative part of the investigation—besides the combination of qualitative and quantitative data—the development of the "modes of biographical agency" (cf. WITZEL & KÜHN, 2000) typology and the question of the relationship between family and work (cf. WITZEL & KÜHN, 2001) were of central interest. [16]

4. The Suitability of the Data for the Purpose of the Secondary Analysis

In order to answer the question as to whether the data from the primary study are suitable for the purposes of the secondary analysis, it is possible to determine diverse criteria for the compatibility of data for secondary analysis (cf. THORNE 1994; HINDS, VOGEL & CLARK-STEFFEN 1997; HEATON 1998) which we use in the following. It is perhaps most important to examine whether the research questions of the secondary analysis are covered by the original data. [17]

The fit of the samples and of the research questions

The primary study looked at the shaping of the biography and the typical course of the transition of young adults from their vocational training into gainful employment, and during the first years of gainful employment. The data refer to the commonest and most typical apprentice-based occupations under both favourable and less favourable labour market conditions. As the gender aspect is also sufficiently taken into account, it was possible to assume that the database ensures sufficient breadth of variation for the secondary analysis. [18]

The rather wide and more fundamental research approach concerning the shaping of the participants' biographies with reference to their individual orientation and actions called for a rich fund of data, which was not limited to a few isolated themes. [19]

The accounts respondents gave about their training and work experience included descriptions and evaluations of skills acquisition in answer to the question about learning of the working-process. Their statements concerning expectations in their life course and their reflections on career prospects formed the basis of the data for analysis of the biographical context and its relationship to work-process knowledge. [20]

The fit of the methods

The primary study used "problem-centred interviews" (WITZEL, 1982, 1989, 2000) for the collection of information, which combined dialogic with narrative techniques. The flexible process demanded on the one hand the use of previous knowledge and previous interpretation in the interview for fruitful enquiry, and on the other hand the use of a communication strategy that would reduce the risk that the thematic interests and prejudices of the interviewer would obscure the point of view of the person being questioned. This gave the interviewees much more scope and support for the reconstruction of their subjective viewpoint and allowed for the correction of misunderstandings on the part of the interviewers. From the point of view of interview technique, it is possible to expect valid statements regarding individual learning processes. [21]

The longitudinal approach with three survey waves makes it possible to research the process of learning in work and career, i.e. the possibility to check our original thesis for the secondary analysis: that the work-process knowledge of young adults is embedded in career process learning. [22]

The primary study followed the approach of "grounded theory" (GLASER & STRAUSS, 1998) and the coding process put forward by STRAUSS and CORBIN (1996). Correspondingly, no theory was imposed on the data, so elements from the various phases of the evaluation process for the secondary analysis can be used. This aspect is examined in more detail in Section 5. [23]

Basis of the data, and its documentation

The data of the project are easily accessible and re-usable because of the digitalisation and the integration of the enormous quantity of data (n=273 interview transcripts, and more than 770,000 lines of text) in a digital text databank7). [24]

The need for useful means to enable re-use of existing data arises first not during secondary analysis, but in principle during the investigation itself, because systematic access to the data is a central prerequisite for the continual evaluation work for each and every member of a research team. Only through continual re-analysis can imaginative interpretation be made possible, and the validity of the proposition be assured. Beyond that there are further reasons to worry about a systematic data-retrieval system: the amount of time the panel is able to sit; the problem of possible changes of research personnel (perhaps because of specific career conditions at the university); and the use of the data for gaining further qualifications after the end of the project itself. [25]

In addition to securing access to the original data through a text databank, project documentation also exists, in which essential information about the research project is summarised. This also contains the definitions of the text databank codes, and the complete publication list for the project. [26]

In the following section it will be shown, that not only the original data but also the coding of the primary study can be used for secondary analysis. [27]

5. The Use of the Coding of the Primary Study

In general the demand for data for secondary use is predominantly limited to raw data, instead of including pre-existing coding in the use of any such data (cf. the note of FIELDING, 2000, Section 28). The widely held prejudice that the use of a coding- and category-system of a primary study would be at odds with an inductive analysis8) of original data stems from equating computer-assisted qualitative data-analysis (CAQDAS) with a deductive data analysis procedure. This may also be connected with the commonly applied term "text analysis programme", which gives the impression that the programme contains analytical categories, the use of which delivers the final interpretation results. Therefore the following explains the use of a CAQDAS programme (see in detail KÜHN & WITZEL, 2004). [28]

The respective text analysis programme is in this respect primarily a text administration programme as it contains the digital data of the current project, i.e. making the data systematically available. The "analytical" in the programme further refers to a system which enables flexible and complex access to single or multiple text passages. This function should facilitate the evaluation of qualitative interview data in that it supports the finding of similarities, differences, and connections between the contents of different passages. [29]

When at least n=20, approx. 40 A4-pages long, openly conducted interviews have to be analysed, it is easy to lose the overview. Therefore the researcher has to develop an organisation schema, such as that provided by a category- or code-system. In earlier times a project databank would be built, in which excerpts from interview-text copies would be cut out, sorted according to theme, and stuck on cards which were categorised by code. This laborious method of building a card-index system was called "cut and paste": today the computer serves not only to relieve this task, but also makes possible analyses on the basis of larger samples and longer interviews. [30]

The CAQDAS programme does not analyse text passages, but instead its categories or codes permit exact and rapid access to thematically relevant text passages. It does this in the form of a retrieval function, which all current computer-supported text analysis systems provide: horizontal retrievals recover text sequences in single interviews, and vertical retrievals search for text sequences over more, or even all, interviews conducted. Different combinations of codes can be applied according to Boolean logic or, (in order to stay within the metaphor of a card-index system) arbitrary combinations of cards with single statements or text sequences from a huge card index can be created. [31]

For this use of a CAQDAS programme, indexing or allocating categories or codes to the fully transcribed interview text is necessary. In the process it is certainly possible to use a system of categorisation which ex ante is derived from available theories. Equally, it is also possible to use an approach for avoiding theoretical presumptions and constraints in the tradition of grounded theory (cf. GLASER & STRAUSS, 1967), provided the code system possesses the heuristic function of a "container" (RICHARDS & RICHARDS, 1995). This card-index file, or container, collects text passages with the help of concepts which are extensive but poor-in-theory, and which are developed from the themes of the interview guidelines or from sifting through the interview texts, and which can be modified during the coding process. These codes are not to be understood as categories, which come at the end of an evaluation process, but rather as thematic collecting-categories, which offer assistance in the search for suitable material from the data for further analysis and the theoretical term-construction associated with this in every phase of the evaluation process. It is precisely grounded theory which requires, in advanced recognition processes, constant re-analysis with access to the original data and has great similarity to the procedure of a secondary analysis. [32]

In order to present the secondary use of the primary study9) data collated with the help of the CAQDAS programme, we will first explain its category system. [33]

The code system of the primary study

The code system of the primary study consists of three parts, which are presented in overview in the following (Table 1). Following this are the case characteristics10) of the interviews (see Table 2) and the thematic (see Tables 3 and 4) as well as the chronological biographical codes, which will be discussed in more detail in the next section.

|

Temporal-biographical codes 1 Chronology after vocational education and training 1 1 Stage 1 1 1 1 Stage 1: Aspiration 1 1 2 Stage 1: Realization 1 1 3 Stage 1: Balancing 1 1 4 Stage 1: Information 1 2 Stage 2 1 2 1 Stage 2: Aspiration 1 2 2 Stage 2: Realization ... 2 Background 2 1 College/university education 2 2 School education 2 3 Vocation 3 Dismissed and thwarted options 4 Career perspectives 4 1 College/university education 4 2 School education 4 3 Vocation

Thematic codes 5 Work and profession 5 1 Content 5 2 Income 5 3 Company 5 4 Career prospects 5 5 Performance 5 6 Acquisition of competence 5 7 Working hours 6 Social network 7 Family and partnership 7 1 Family background 7 2 Partner 7 3 Marriage 7 4 Division of labour 7 5 Living 7 6 Partnership 7 7 Family founding 8 General orientations/attitudes 8 1 General ideas about life 8 2 Self-identification 8 3 Overall balancing 8 4 Gender-specific statements 9 Leisure |

Table 1: Overview of the code system (from KÜHN & WITZEL 2004, para.55) [34]

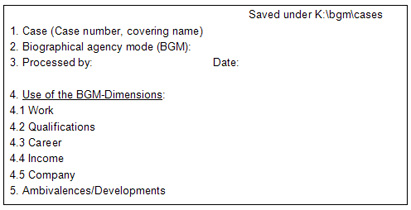

The following illustrations refer to the code system of the case characteristics and to the thematic codes.

|

Table 2: Extract from the code-schema "Case-characteristics" [35]

|

Thematic codes ... 5 Work and occupation 5 1 Content 5 2 Income 5 3 Company 5 4 Career prospects 5 5 Performance 5 6 Skills Acquisition 5 7 Working hours 6 Social network 7 Family and partnership 7 1 Family background 7 2 Partner 7 3 Marriage 7 4 Division of labour 7 5 Living 7 6 Partnership 7 7 Family founding |

Table 3: Extract from the category system of the primary project [36]

Each code possesses a code number. The category "Income", for example, has the code number 5 2. This number provides information about the position of the individual code in the system. For example the codes for "Work tasks", "Income", and "Company" belong to the thematic area of "Work and Occupation": and the codes for "Family of origin", and "Partner" belong to the thematic area of "Family and partnership". [37]

The documentation of the category system with the definitions of the individual codes is indispensable for secondary analysis. It is the basis for viewing the data not only in order to judge the usefulness of the data for secondary analysis, but also for aiding the search process for suitable empirical pieces of evidence in the actual secondary analysis. As an example we now list the definitions for the main theme of "Work and Occupation".

|

5/1 Work and Occupation—Contents of Work Statements in which the respondents describes their occupation, tasks they have to cope with, including statements concerning meaning of work, interests, preferences, aversions, balancing of contents of work. 5/2 Work and Occupation—Income Comments referring to the personal income as well as to general occupational income situations. This also includes interview passages on financial support (i.e. government student loan or parental help), allowances, household money, financial or cost problems. 5/3 Work and Occupation—Company Statements about the company or employer as an organisation, i.e. work climate, social coexistence, comparison of firms, comments about the boss as a gatekeeper, the application situation for an apprenticeship and the question of being hired permanently by the company, responsibilities ("what should I do"?"), the position within the company hierarchy and the educational quality. 5/4 Work and Occupation—Career Prospects Comments on work opportunities, educational prospects (promotion prospects), job security, assessment of the actual and general labour-market situation, financial support by the employment office. Related to what is being or has been striven for (or considered) by the respondent and not related to her/his current status we distinguish between university education (5/4/1), school education (5/4/2), occupation and other (5/4/3). 5/5 Work and Occupation—Performance Statements regarding performance in a work and company context, i.e. perception of performance expectations ("too lax," "not enough satisfaction," "stress," "pressure to perform"), the degree of motivation and the reason for it (promotion prospects, money, sense of duty, enjoyment of work, self-confidence through success, social recognition etc.), the attitude towards job performance and principles like achievement principle, assessment of one’s own performances, explanation of one’s own performances (talent, for instance). 5/6 Work and Occupation—Skills Acquisition Comments referring explicitly to the acquisition of skills and qualifications in the job and for the profession like further education, schooling (degrees), university degrees, vocational education, and, moreover, interview passages in which questions like "what are your qualifications?" and obstacles or aids are discussed. 5/7 Work and Occupation—Working Hours Interview passages relating to the temporal organization of work, including vacation regulation, time scheduling for work. |

Table 4: Definition of the categories on the generic subject "Work and Occupation" [38]

With the chronological biographical codes it was necessary to fall back on an "ARB model", (WITZEL & KÜHN, 2000) which was developed over the duration of the project work. This model described three elements: aspiration (Aspirationen) (A), realisation (Realisationen) (R), and assessment (Bilanzierungen) (B). It served—like the other codes previously—the collection and the sorting of the actions which had been identified in the qualitative interviews, the rationale for these actions, and the subjective processing of the results of these actions. So the code "Aspiration" for example—like the other two model elements—did not correspond to some theoretically determined term, but recorded in an open way the rationale for actions, with which the work interests, motives, designs for action, and plans could be reconstructed in the later evaluation. [39]

With "realisation", remarks regarding concrete actions taken in order to realise aspirations are recorded. As they manage the transitions of status and the demands of their careers, the protagonists direct their attention to opportunities, which they can realise, and to restrictions, which they can try to avoid. [40]

"Assessment" is the individual evaluation of the results of decisions, actions and of experiences in context, within the framework of the individual's biographical situation. The individual resumes contain the purposes attributed to performed actions, which refer to forms of processing passages/transition experiences and maintaining biographical identity. "Assessment" does not only contain retrospective reflective passages: it also contains prospective reflective passages, which result in the re-evaluation of aims, expectations, and plans. [41]

It is possible to see that various points in a career are assigned the codes A, R, and B. These career points are those which the individual passes through on the time axis of his/her participation in various institutions and organisations: apprenticeship, workplace, unemployment, change of workplace, national service, work retraining, technical high school, etc. It is possible, through this, to analyse the actions of the individual in an institutional context. This assignment of codes is also meaningful for the secondary analysis, because with it learning requirements in specific work and educational contexts, and their evaluations, can be differentiated. [42]

The use of the retrieval function for the secondary analysis

On the basis of the described category system, single codes can be selected and with the help of the CAQDAS programme (in this case NUD.IST) so-called "retrievals" can be created. The following example (Table 5) is an extraction from a horizontal, i.e. case-related, example of code 5 3 "Work and Occupation-company" for the case of Martin CM (CM: car mechanic) which gives information about a variation of work-process knowledge.

|

Q.S.R. NUD.IST Power version, revision 4.0. Licensee: WP401028-105-95575. PROJECT: A1, User A1, 14:44, 10 Aug, 2004. ********************************************************************** (I 729) //Index Searches/Index Search916 *** Definition: Search for (INTERSECT (30 9 98) (5 3)). No restriction +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ +++ ON-LINE DOCUMENT: 1240103 +++ Retrieval for this document: 584 units out of 1242 = 47% … +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ +++ ON-LINE DOCUMENT: 2240103 +++ Retrieval for this document: 543 units out of 1689 = 32% ++ Text units 660-806: … 691 A: 692 Yes in the training, I think so. In the 693 apprenticeship. I trained by XX, and we had there a 694 very good training, because we were quite simply never 695 in the daily operation, we 696 never had to work productively during the 697 three-year apprenticeship, but we were 10 apprentices per apprentice-year 698 we always had a trainer, and then there would be a 699 week, partly in two-weeks blocks, when we only did theory 700 in the classroom and then the topic, which 701 we had dealt with, would then in one week 702 be practised on an actual car. So, we have, 703 in school we spoke about overhauling an engine, and then 704 the trainer organised an XX car, which needed an overhaul 705 and then we spent a week on the car 706 and applied the theory we had learnt 707 practically, we took the motor to pieces, 708 then once again we were told where to look, 709 we discussed this and that, look at this, this looks like this, 710 and it has to be done in this way. And when I have done 711 this over the whole area and naturally now more intensively 712 do it over the electronic area, then it was probably 713 an optimal training. And when I think about it now … |

Table 5: Retrieval Martin CM (translated from the German) [43]

The interviewee Martin CM is speaking here about his learning experience from his time as an apprentice, and positively evaluates (in bold) the combination of theoretical and practical training. He explains this assessment by referring to the splitting of the apprenticeship training into blocks of two weeks, in which not only theory and practice were alternately taught, but a close connection between the two was made: the theoretical teaching was followed by practical application on a car while at the same time referring back to the theory (rows 708/709). From the point of view of providing experience of problem areas he had already learned about, and also of providing a perspective on electronics, Martin CM judged this combination of the theoretical and the practical to be an ideal apprenticeship training. [44]

That is just one example of a possible retrieval. In the following evaluation similar or contrasting remarks and cases are searched for, in which further retrievals for other relevant codes are constructed. In the following the retrieval from the code 5 1 "Work and occupation—work tasks" (Table 6) for the case of Melissa F. (hairdresser) is presented and discussed from the point of view of its use for secondary analysis.

|

Q.S.R. NUD.IST Power version, revision 4.0. Licensee: WP401028-105-95575. PROJECT: A1, User A1, 11:59, 10 Aug, 2004. ********************************************************************** (I 708) //Index Searches/Index Search895 *** Definition: Search for (INTERSECT (30 9 129) (5 1)). No restriction +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ +++ ON-LINE DOCUMENT: 1250204 +++ Retrieval for this document: 1395 units out of 2388 = 58% … 794 I say, it isn't bad, but some things should 795 be improved in the schools, some things. 796 you learn things from the teachers so, at work you can't 797 ever use it, because, you can do one customer, 798 then that's it. You have to do the work a bit quicker 799 now and then. That it can't always be so exact 800 is normal, like in every job. But then again, 801 you should do it like this (unclear), so 802 now, in the exam you are then. You learnt it so at work 803 you have it in you, but the vocational school says you have to do it 804 also like that and then the examiner says 805 That's worthless, although you are generally well experienced 806 with it and the customers were satisfied, that is exactly the 807 problem there,and I think, they should forget about the practical 808 work in the school and do it at work. 809 That there (unclear) at work. That then the … |

Table 6: Retrieval Melissa F. (translated from the German) [45]

Given her experience in the vocational school and unlike the case documented above, Melissa F. documents her idea of a contradiction between theory and practice (in bold). What the teachers in the vocational school teach, and what is required for the examinations, does not match the requirements of the workplace. The teachers' quality standards are contradictory to the working practices in a salon, which are constantly under time pressure, and contradict the routine she has learnt. Even the practice-oriented teaching, to which we here have assigned the term "theory", obviously contradicts work practice. Melissa F. justified her preference for learning by doing and the rejection of academic qualifications by using as her success criterion customer satisfaction, despite a shorter time for the execution of any particular piece of work, i.e. she rejects the usefulness of practical learning in favour of the rules of the hairdressing firm she works for. We interpret these described rules as a business-serving ideal of maximising customer numbers while simultaneously aiming to provide satisfactory customer service. The decisive qualification consists therefore of the acquisition of knowledge through experience, which is to be gained in work practice for the salon, rather than in the vocational school. [46]

These two cases exemplify the empirical result of the two forms of work-process knowledge and thereby provide a partial answer to the first research question about the composition of work-process knowledge. In the one case work-process knowledge creates an intersection of theoretical and practical (or experimental) knowledge (Martin CM). FISCHER (2005, p.308) reports results of BOREHAM et al. (2002), a summary of the results of European research, which exactly correspond to the variation we found. It is work-process knowledge which is "mostly acquired in the process of working, through 'learning by doing', but which does not exclude the use of theoretical knowledge related to the subject" [translated from the German]. In the other case the work process knowledge contains a contradiction between theory and practice (Melissa F.), a perhaps newer finding, about which nothing is reported in the above-mentioned publication. [47]

So the text retrievals serve to find text passages on the qualification theme in the evaluation process at the level of open coding, which, in order to compare them with each other, follows the principle of "maximum and minimum contrast" (GERHARDT, 1986, p.69), in order finally to be able to develop further variations of the acquisition of work-process knowledge. [48]

Until now we have tried to explain the use of open-coded data for our secondary analysis. Under certain circumstances it is possible to use the theoretical concepts of the primary study for the secondary analysis. This type of use we see as virtually necessary in order to be able to analyse the embedding of variations of the acquisition of work-process knowledge into the biographical context. [49]

6. The Use of the Theoretical Concepts of the Primary Study

A central precondition for the use of theoretical concepts from the primary study for secondary analysis is the possibility of reconstructing the process of theory generation, i.e. comprehending the extraction of dimensions and categories from the empirical data. As has already been shown (with open coding), this procedure, according to the basic principles of grounded theory, is suitable for such a reconstruction, as a condition for finding links for setting questions in the secondary analysis. The whole process of changing inductive-deductive coding includes, in addition to the open codings, the further analytical levels of the axial and the selective codings, whose respective interim results are usable for secondary analysis. The conditions for this are comprehensible documentation of the analytical results of the individual analysis levels11) (for example in the form of memos), the possibility of referring back to the original data at every level, and the disclosure of presumptions and knowledge of the question setting of the primary study. [50]

To return to our empirical example: on the basis of the analysis of individual cases it is clear that there is a wide variation in the connection between practical and theoretical learning. From this we have assumed that this variation has to do with specific forms of biographical orientation and actions as the result of pre-work and work socialisation processes. (See the second research question of the secondary analysis.) Such forms of orientation and action exist in the primary study as theoretical concepts in the form of a typology, which is introduced in the following. [51]

The empirically based typology of the modes of biographical agency (BGM) (WITZEL & KÜHN, 1999, 2000) were based on the following research questions: (How) is the scope for action for the realisation of work expectations used? What consequences does the self-socialisation of young adults—with its inherent experiences of inequality—have for maintaining or changing orientation and action patterns during the transition to work and in the first years of pursuing a career? The BGMs are not therefore aimed at the competence or identity theoretical basis of mastering occupational-biographical requirement structures; but answer the question "In which of various forms of orientation and actions do young adults structure their occupational status passages, and take over responsibility for their course?" [52]

The BGM have to do with a longitudinal typology, with which the orientation and actions of the young adults, from choice of occupation, through entry into vocational training and gainful employment, to five years after the end of the vocational training, were reconstructed on the basis of retrospective and prospective data. They include the—for young people—meaningful time period of the transition from pre-work to work socialisation, and the development of experiences in the first years of their work. Biographical agency modi were activated according to specific context; did not arise only in selective decision situations but in the process of tackling the encompassing social requirement structures of the life course. They are extraordinarily stable. [53]

By systematically contrasting cases and analysing them with the help of the above-mentioned ARB model the theoretical concept of the BGM was elaborated and further developed using a small sample of some 20 cases. Because of the observation window of only three years, the formation of the types had to be limited to the situational issues of the status passages into work, rather than to the consequences of individual decisions regarding courses of action. Two further information-collecting phases then extended the observation window by approximately seven years and enabled the use of the previously defined concept of the BGM as an interpretation hypothesis for the theory-led analysis and reanalysis of approx. 50 cases. Finally, "selective coding" in the sense of STRAUSS and CORBIN (1990), using the remaining empirical material from more than 40 cases, led to a reformulation of selective type dimensions. The typology was at the same time reduced to six biographical agency modi12). [54]

N=91 comprehensive case studies and allocations to the six types formed the basis for the use of the secondary analysis. These allocations, on the basis of the five dimensions described in the following, are very significant for the secondary analysis questions on work-process knowledge. Namely, the dimensions describe the shape of, or the connection between, various biographically relevant aspects, and at the same time the important subjective relationship to work, qualification and company. [55]

The dimension "Work tasks" is concerned with the content and the conditions of work. Among these are, for example, remarks in which the meaning of "room for manoeuvre and shaping" in the actual work is clear. Using the data which can be identified and analysed through these dimensions the following questions can be answered: Is narrowly limited room for manoeuvre accepted? Is the expenditure of labour minimised? Is more room for manoeuvre for engaging with the company, new challenges, and self-realisation sought? Is work motivated by an overwhelming interest or by practical considerations, as a means to make ends meet or to furthering one's business? [56]

The dimension "Qualification" is concerned with the range of orientation and activity of the young adult in higher and further education. The reconstructive evaluation work leads to the question: "How far do young adults passively submit to company demands for qualifications, or do they strive to educate themselves, to go beyond narrow company requirements (for example with a course of study) and to build up systematic skills or pursue personal interests?" [57]

The dimension "Career" is concerned with the subjective attitude of the subjects in pursuing their career. On the other hand, this orientation—as in the other dimensions—is extended to include corresponding courses of action. The evaluation of orientation and actions results in various ways of protecting the working life, such as employer loyalty and changing employer, which suggest that a professional ceiling has been reached, and a more open vocational development, such as using the company career roadmap, securing a large number of career options, or completely holding open one's work prospects, partly accepting risks to continuity. [58]

The dimension "Income" encompasses the subjective meaning of income from gainful employment for the shaping of the occupational biography. Income can, therefore, be seen as a means of satisfying personal demands, as an expression of the value assessment of the effort put in and performance, or more as a guarantee of personal independence. Various orientations and actions are reconstructed, which indicate that company wage-guidelines are either accepted or held to be less meaningful; that the young adults try to optimise the relationship between effort and income; that a higher income is expected as a result of efforts to rise within the company and in recognition of better performance; that those questioned expect that nothing more than occupational independence can guarantee financial independence. [59]

"Company" is the last dimension. This is concerned with the subjective meaning of the company as the organisation of work and social environment. Here the relationship to the work hierarchy, the work demands, and the company morale are important. The latter encompasses the quality of the social relationships in the organisation and the quality of the working relationships. Orientations and actions range from identification with the company's rules, through protecting the boundaries of reasonableness, the search for recognition from superiors, to a more pronounced distance from the company through the extension of work options, and autonomy through stressing personal lifestyle and an individual attitude towards the company structures (independence). [60]

On the basis of these options for orientation and action in the individual dimensions, we have constructed six types which can be summarised in three general categories (see the following overview): an open form of biography shaping with efforts towards an extension of room for manoeuvre, a somewhat more closed form of biography shaping restricted to maintaining the current occupational status, and a form of biography shaping which is characterised by striving for autonomy. [61]

The BGM-group "The development of career ambition" encompasses on the one hand the BGM "Career-orientation", by which the young adults restrict themselves to company career patterns when viewing their options: on the other hand the BGM "Optimisation of Opportunities" where those questioned try to go beyond the company "room for manoeuvre" and keep as many work options open for themselves as possible. [62]

In the group "Career ambition" is the BGM-group "Restriction to status arrangements" with the BGM-characteristics "Identification with the company" and "Wage-earner habits". Here the shaping of the biography is viewed as being more or less completed, limited room for manoeuvre is accepted as given. Subjects who come under the BGM "Wage-earner habitus" strive for job continuity and come to terms with a lower occupational level through striving towards a favourable relationship between personal effort and material reward (income, conditions of work). With the modus "Identification with the Company" the young adults see themselves at the end of their career-development possibilities and hope that they have found, through identification with the company demands, a kind of "home" with personal acceptance and a secure job. [63]

With the BGM-group "Striving for the Acquisition for Autonomy" we refer to a peculiarity of the last two types: the subjects pursue autonomy, and thereby distance to dependent employment as a basic principle of their orientation and activity. Subjective standards of working life can be personal further- and self-development (BGM "Shaping of personality"), or self-determination regarding the company organisation (BGM "Habits of independence").

|

|

Work |

Qualifications |

Career |

Income |

Company |

|

Status arrangement:

Identification with the company |

Carrying out work according to the company's requirements. Orientation to a tightly-limited area of activity. |

At best prepared to develop adaptation skills. |

Remains in company or in the occupation, continuity, secure prospects. |

Prepared to accommodate themselves to the given conditions, partially at a low level. |

Company as "home", familiar work-climate, trust in the care of superiors.

|

|

Wage-earner habitus |

Work as a necessity for material reproduction, as effort which is set in relation to income earned. |

At best prepared to develop adaptation skills. |

Continuity, change of company and occupation possible for improved pay and working conditions. |

Optimisation of the relationship between effort and income, prepared to do more work for a higher income. |

Resistance of imposition on work conditions and payment, job floor solidarity. |

|

Career ambition:

Career orientation |

Striving for a growing area of responsibility, specialisation as "expert" or for leading position. |

Calculated development of skills the skills serve the purposes of paid employment. |

Company timetable-strategies with concrete idea of aims, secured step-by-step. |

Sign of occupational and company status, recognition of a higher level of performance. |

Oriented to options regarding company conditions, recognition of superiors important. |

|

Optimisation of opportunities |

As varied as possible, new challenges, gaining of experience, room for manoeuvre and creativity important, acceptance of responsibility. |

Broad development of skills , successive accumulation of qualifications. |

Rising within the occupation, many alternative options. |

The recognition of a high level of performance. |

Unlimited occupational possibilities in the company. The company is one alternative among many. |

|

Autonomy gain:

Personality growth |

Work as space for experiencing personal further development and the self-realisation. |

Interest in further education not necessarily connected with occupation and career, but stems from personal motives. |

Career-shaping options kept open, acceptance of interruptions to the occupational biography. |

Subordinate to the self-realisation. |

Distance from company demands, autonomous lifestyle. |

|

Self-employment habitus |

Work: work as a means to occupational success. |

Professionalisation according to need. |

Orientation to business principles, continuity, secure prospects. |

Chance for higher income and financial independence. |

Distance to the company hierarchy, autonomy: "own boss". |

Table 7: The typology of the modes of biographical agency (translated from WITZEL & KÜHN, 2000, p.17) [64]

In the following section we will use this typology to answer the second research question regarding the meaning of biographical context for work-process knowledge. [65]

7. Central Results of the Secondary Analysis

Our opening hypothesis was firstly that various forms of work-process knowledge exist, and that they should be identified in the secondary analysis. These forms of work-process knowledge could be obtained with the help of the coding schema based on the CAQDAS programme. [66]

Secondly, we also expected that the method of creating the occupational biography plays a central role for these variations. We subsequently assumed that the characteristics of the work objectives, interests and learning motivation of the employees are the elements of a career process, which can be seen as a result of the self-socialisation process in training and work. For this reason the BGM-typologies could be used for the secondary analysis. Especially two of the BGM dimensions—"work tasks" and "qualifications"—can be connected with the type of shaping of the biography through the help of the answers obtained with the use of the CAQDAS programme. In the secondary analysis we were thus able to use the case processing, in which the basic data for the allocation of the individual cases to the respective BGM are contained. We were also concerned with the results of the case analyses along the BGM dimensions13), together with empirical verification in the form of verbal quotes. These case processings were analysed in the primary study according to the following schema.

Figure 2: BGM analysis schema (translated from the German) [67]

To explain the results of the secondary study we limit ourselves in the following to the BGM groups "Status-arrangement" on the one hand and "Career/ambition" on the other. In relation to the BGM "Wage-earner habitus" and "Career-orientation", both of which are in the two contrasting BGM groups, we were able in the presentation to use the previously cited cases of Melissa F. (BGM "Wage-earner habitus") and Martin CM (BGM "Career-orientation") (see Section 5). [68]

In the BGM-group "Status-arrangement" we find subjects in trades, industries, and services who have mostly already experienced a school "cooling-off" process. They refer to the school selection results of the HAUPTSCHULE and the REALSCHULE as proof of their lack of theoretical ability and rely on the development and recognition of their practical skills. Hence, the common ground between the BGM "Identification with the company" and "Wage-earner habits" is to be found in the preference for experiential knowledge. Typical for these learning or knowledge forms is the stress on a polarity between theory and practice. In so doing the subjects consciously reject the significance of theory. [69]

The interest in qualifications can in extreme cases be limited to direct execution of work. However, if a clearly outlined "effort-to-qualify" is judged to be directly useful for improved conditions regarding work and income, then we find that some subjects, with the BGM "Wage-earner habitus" have an approach to forms of learning that goes beyond simple learning through experience. The subjects want to escape from burdensome working conditions like dirt and monotony and to work in occupational "niches", in which the work is cleaner and easier. It is possible to deduce from their actions another attitude to gaining qualifications that they are actually unconscious of. These subjects reject theoretical learning explicitly when interviewed, while on the other hand in some areas of their described work behaviour they combine practical tasks with the gaining and the use of theoretical knowledge. [70]

Interestingly, though, scepticism towards theory leads to limited acquisition of work-process knowledge, some subjects deliberately ensure that the only knowledge which is acquired is that which proves useful for their own work practice. That means that they personally develop an interest in ensuring that practical and theoretical knowledge can be integrated. [71]

As is clear from Section 5, Melissa F. believes that she would do many things wrongly if she were to trust "theory". Correspondingly she pleads the case—looking back on her training period—that the vocational school should not concern itself with working practices at all. This attitude of rejection makes it clear—as the quotes to the Dimension "Work" show—that living with vocational qualification requirements on a more "practical" level and its inherent consequences for shaping one's life does not necessarily go hand in hand with a subjective assessment of failure to cope with the "theoretical" requirements in school or vocational school. Melissa F. felt better at work because her way of dealing with work—routine work carried out according to structured rules—led to her being accepted by her superiors and thus produced a better working atmosphere.

"… and then, you have worked up to that point, until maternity leave, and in the end you are really happy when you get out (laughs) ... But otherwise, regarding the work, it was really super in the company, everything went really well, I have to say, better than before. And it's a pity that I am no longer there, on the one hand, and otherwise, I think, that not so much has changed, I'd like to say ..." (III,76).

After maternity leave she wants to go back to work. This will not be possible with her old employer, and apart from this the workplace is too far away from the kindergarten, causing organisational problems. She is looking for a job in her neighbourhood.

"... and I don't really care what I do. There are lots of things which are fun to do" (III,692).

"You have to be a bit...you have to be flexible, you can't move away from the standard, I only want this (...) or I want to have a career, a normal job, once you've got one, then, my God, what is that supposed to be, I can also have a career if I, if the boss, OK I do a super job and he promotes me with praise or something. That achieves more than if I work as a super top-manager and everything stinks" (III,5501) (extract from the case study of Melissa F.). [72]

For the dimension "Qualification" we will give only one quote, which is to illustrate that for the BGM "Identification with the company", starting a family is a typical alternative to vocational qualifications. "You can't do a super job and at the same time bring up a child. When people say, that even as a mother I want to have this or that, then I say that for me I have priorities, and I have already said that the child is simply more important for me." (111, 6072) [73]

For the BGM "Optimisation of Opportunities" and "Career orientation", both allocated to the BGM group "Career/ambition", the acquisition of knowledge has a central function for developing skills, and for realising efforts for promotion. The further education culture of the bank gives the appearance that the various work development possibilities are only based on in the motivation of the individual. Individuals with the BGM "Career-orientation" strive to—in response to working requirements in banks and savings banks and to demands for flexibility at work—constantly develop their skills. Theory and practice are not self-exclusive from a subjective point of view here, unlike with the BGM group "Status-arrangement". Rather, concrete work requirements necessitate the acquisition of work-process knowledge in practice, in connection with internal courses, which the bank expects employees to take part in. The bank workers make this interest in work-process knowledge as a combination of theory and practice with the BGM "Career-orientation" their own. Their acquisition of knowledge goes beyond the demands of their individual work place and serves the also frequently self-desired flexible skills of someone capable of switching from task to task within the company. The bank workers are also quite prepared to voluntarily expand the areas of their own work activity within the general division of work responsibilities. [74]

Also those subjects with the BGM "Career-orientation" who managed to find a position commensurate with their qualification in the car trade are interested in the details of the technical basis of their work. In this connection we use the example of Martin CM, who spoke about the integration of theory and practice in his training period (Section 5), which served as a model for his further learning ambitions. The remarks could be connected with the analytical results of the allocation to this type. His ideas regarding the combination of theory and practice are a part of the recorded description in the dimension "Work" of his intention to acquire expert knowledge. We quote the following extract from the case-processing of Martin CM:

Independent work: "then the work is simply done, independently, and that is just what interests me. Not that, which is thought out for me, that I now have to do this or that, but that I myself look for faults and repair them" (I, 573).

"Lots of mechanics are not capable of making a diagnosis. Then the master craftsman has to be asked again, and it is exactly these tricky things which excite/interest me" (I, 695).

He wants: "to have a real contact with the car, (...) and then that would be to make diagnoses in difficult cases and such things. That would really appeal to me. And if that was the case, then I would stay with the job" (I, 807).

"Yes, and in the company I have now tried to develop a bit of a special area for myself, so that I'm not one of those everyday part-changers, but that I have specialised in fuel injection units, catalytic converters and so on, in the electronics sector, I have specialised in that. With the help of the company, obviously!" (II,42) [75]

In the following, extracts from the dimension "Qualifications", in which the calculated skill development is the subject of the comments of Martin CM, round up the picture of the connection between the shaping of the biography and work process knowledge/work process learning:

He had several offers of apprenticeships: "... and then I thought about where I could get the best apprenticeship, and acted on that" (I, 256). "As an apprenticeship it is, in my opinion, the ideal. The one thing we didn't learn, is how to work under the pressure of time" (I, 418, 434).

"... it was actually already obvious to me that I didn't want to stay a mechanic, but that I wanted to stay in the trade, eventually become a master craftsman, and then in the trade somehow move up into some big company" (II, 18).

"... the company supports me, to be honest, wherever it can. It sends me constantly to training courses, to ex-company courses, to company courses, and also tries to support me in my attempts to become a master craftsman early" (II,24,155).

The reason for his efforts regarding further training: fuel-injection systems "are the technology of tomorrow, and I still have something to learn there. I have gaps in my knowledge there" (II, 231).

Qualifications such as organisation, work-planning, division of labour, and training of personnel were "learned" by observing his predecessor (II,522). He had asked some of his previous trainers in public service, and they supported him. (III, 539) He was now attending management training courses s and a workshop supported by the company (III,557) (extract from the case-study of Martin CM). [76]

The systematic connection between theory and practice in work-process knowledge and work-process learning is reflected in the equally systematic efforts towards acquisition and implementation of occupational skills. [77]

According to our experience with secondary analysis, the primary study should fulfil certain conditions, which can be summarised as follows:

There must be a database containing a sufficiently large amount of data with completely transcribed interview texts, which have been made easily accessible through digitalisation.

The survey methods allow those questioned enough room for the development of their point of view.

The data are assembled in files in a CAQDAS programme and allow, through the use of heuristic and broad codes, quick and systematic access to relevant passages of text. This is on the one hand to check the usefulness of the data for secondary analysis, and on the other hand to simplify access to data during the evaluation phase of the secondary analysis.

Documentation exists in which all the essential information regarding the research project is assembled. This contains among other things the definition of the databank codes and the complete publication list of the project.

The broad and fundamental research questions regarding the shaping of the subjects' biographies in respect of their individual orientation and actions called for a rich fund of data, which is not limited to a few single thematic aspects.

The primary study does not use theories in the tradition of the normative-deductive paradigm, but is instead bound to a theory-generative process in the sense of grounded theory.

At all levels of the evaluation, the primary study must allow an insight into the respective documented findings, perhaps in the form of case studies and memos.

These findings can be traced back to the original data. [78]

1) This is the English translation from a German text, published in FQS in January 2005. FQS thanks the authors for providing the English version and Louise CORTI for copy-editing, September 2007. <back>

2) This contribution is based on the lecture "Secondary Analysis of Panel Data: Establishing and Using a Text Databank", held at the "RC33 Sixth International Conference on Social Science Methodology" in Amsterdam in August 2004. <back>

3) The A1 subproject of Bremen University’s Collaborative Research Centre 186 "Status passages and Risks in the life course" (see http://www.empas.uni-bremen.de/lnks.htm, joint project A1/B1) is a longitudinal study (panel) which had already ended by that time. The authors of the present study were themselves participants in the primary project. <back>

4) "Work Process Knowledge and Work Related Learning in Europe", meeting of CEDEFOP and ITB, University of Bremen, 15th/16th June 2001. <back>

5) Funded and published by CEDEFOP, European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. <back>

6) "New perspective/conceptual focus" (HEATON, 1998), "analytic expansion" (THORNE, 1994). <back>

7) Here the term "databank" stands for the systematic availability and digitalisation of the data which would normally be contained as a document in a CAQDAS programme. <back>

8) THORNE (1994) criticises the common use of a deductive and quasi statistical content analysis in secondary analysis and argues for inductive, e.g. hermeneutical analysis of text materials. <back>

9) Stored in the archive for life-course research: http://www.lebenslaufarchiv.uni-bremen.de/. <back>

10) In other CAQDAS programmes case characteristics are available as variables. <back>

11) Here the secondary use of one’s own data proves to be beneficial. <back>

12) In the quantified reconstruction of this qualitative typology both the individual type-characteristics as well as the distribution of the occupations was broadly confirmed (SCHAEPER & WITZEL, 2001). <back>

13) The dimension ambivalences/developments contains analyses and commentaries on perceived inaccuracies in the allocation of the cases. <back>

Boreham, Nicholas C.; Samurcay, Renan & Fischer, Martin (Eds.) (2002). Work process knowledge. London: Routledge.

Fielding, Nigel (2000). The shared fate of two innovations in qualitative methodology: The relationship of qualitative software and secondary analysis of archived qualitative data. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(3), Art. 22, http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-00/3-00fielding-e.htm [Access: September 17, 2007].

Fischer, Martin (2005). Arbeitsprozesswissen. In Felix Rauner (Ed.), Handbuch Berufsbildungsforschung (pp.307-315). Bielefeld: Bertelsmann.

Fischer, Martin; Boreham, Nicholas C. & Nyhan, Barry (Eds.) (2004). European perspectives on learning at work: The acquisition of work process knowledge (Cedefop Reference Series). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publication for the European Communities.

Gerhardt, Uta (1986). Verstehende Strukturanalyse: Die Konstruktion von Idealtypen als Analyseschritt bei der Auswertung qualitativer Forschungsmaterialien. In Hans-Georg Soeffner (Ed.), Sozialstruktur und Soziale Typik (pp.31-83). Frankfurt/M.: Campus.

Glaser, Barney G. & Strauss, Anselm L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine.

Glaser, Barney G. & Strauss, Anselm L. (1998). Grounded Theory. Strategien qualitativer Forschung. Bern: Huber.

Heaton, Janet (1998). Secondary analysis of qualitative data. Social Research Update, 22, http://www.soc.surrey.ac.uk/sru/SRU22.html [Access: June 8, 2006].

Heinz, Walter R. (1996). Status passages as micro-macro linkages in life course research. In Ansgar Weymann & Walter R. Heinz (Eds.), Society and biography (pp.51-66). Weinheim: Deutscher Studien Verlag.

Heinz, Walter R.; Kühn, Thomas & Witzel, Andreas (2005). A life-course perspective on work-related learning. In Martin Fischer, Nicholas Boreham & Barry Nyhan (Eds.), European perspectives on learning at work: The acquisition of work process knowledge (pp.196-215). Cedefop Reference Series, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publication for the European Communities.

Heinz, Walter R.; Kelle, Udo; Witzel, Andreas & Zinn, Jens (1998). Vocational training and career development in Germany—results from a longitudinal study. International Journal for Behavioral Development, 22, 77-101.

Hinds, Pamela S.; Vogel, Ralph J. & Clarke-Steffen, Laura (1997). The possibilities and pitfalls of doing a secondary analysis of a qualitative data set. Qualitative Health Research, 7(3), 408-424.

Klingemann, Hans D. & Mochmann, Ekkehard (1975). Sekundäranalyse. In Jürgen van Wieken Koolwji & Maria Mayer (Eds.), Techniken der Empirischen Sozialforschung 2 (pp.178-194). München: Oldenbourg.

Kluge, Susann (1999). Empirisch begründete Typenbildung. Zur Konstruktion von Typen und Typologien in der qualitativen Sozialforschung. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Kuehn, Thomas & Witzel, Andreas (2004). Using a text databank in the evaluation of problem-centered interviews. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(3), Art. 18, http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-00/3-00kuehnwitzel-e.htm [Access: September 17, 2007].

Mochmann, Ekkehard (1968). Sekundäranalyse. Ein Diskussionsbeitrag zu neuen Methoden in der Empirischen Sozialforschung. Unpublished manuscript, Cologne.

Mönnich, Ingo & Witzel, Andreas (1994). Arbeitsmarkt und Berufsverläufe junger Erwachsener. Ein Zwischenergebnis. Zeitschrift für Sozialisationsforschung und Erziehungssoziologie, 14(3), 263-278.

Mowitz-Lambert, Joe; Heinz, Walter R. & Witzel, Andreas (2001). Nimmt die Bedeutung des Berufes für die Erwerbsbiographie ab? Diskontinuitätserfahrungen und Berufsbiographien von jungen Fachkräften in den ersten Berufsjahren. Bildung und Erziehung, 54(4), 423-438.

Opitz, Diane & Mauer, Reiner (2005). Erfahrungen mit der Sekundärnutzung von qualitativem Datenmaterial – Erste Ergebnisse einer schriftlichen Befragung im Rahmen der Machbarkeitsstudie zur Archivierung und Sekundärnutzung qualitativer Interviewdaten [50 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(1), Art. 43, http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/1-05/05-1-43-d.htm [Access: September 17, 2007].

Rauner, Felix (2002). Die Bedeutung des Arbeitsprozesswissens für eine gestaltungsorientierte Berufsbildung. In Martin Fischer & Felix Rauner (Eds.), Lernfeld: Arbeitsprozess. Ein Studienbuch zur Kompetenzentwicklung von Fachkräften in gewerblich-technischen Aufgabenbereichen (pp.25-52). Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Richards, Tom & Richards, Lyn (1995). Using hierarchical categories in qualitative data analysis. In Udo Kelle (Ed.), Computer-aided qualitative data analysis (pp.80-95). London: Sage.

Schaeper, Hildegard & Witzel, Andreas (2001). Rekonstruktion einer qualitativen Typologie mit standardisierten Daten. In Susann Kluge & Udo Kelle (Eds.), Methodeninnovation in der Lebenslaufforschung. Integration qualitativer und quantitativer Verfahren in der Lebenslauf- und Biographieforschung (pp.217-260). Weinheim: Juventus.

Schaeper, Hildegard; Thomas Kühn & Andreas Witzel (2000). Diskontinuierliche Erwerbskarrieren in den 1990ern: Strukturmuster und biografische Umgangsweisen betrieblich ausgebildeter Fachkräfte. Mitteilungen aus der Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (MittAB), 33, 80-100.

Strauss, Anselm L. & Corbin, Juliet (1996). Grounded Theory: Grundlagen Qualitativer Sozialforschung. Weinheim: Beltz, PVU.

Thompson, Paul (2000). Re-using qualitative research data: A personal account. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(3), Art.27, http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-00/3-00thompson-e.htm [Access: September 17, 2007].

Thorne, Sally E. (1994). Secondary analysis in qualitative research: Issues and implications. In Janice M. Morse (Ed.), Critical issues in qualitative research methods (pp.263-279). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Witzel, Andreas (1982). Verfahren der qualitativen Sozialforschung. Überblick und Alternativen. Frankfurt/M.: Campus.

Witzel, Andreas (1989). Das problemzentrierte Interview. In Gerd Jüttemann (Ed.), Qualitative Forschung in der Psychologie. Grundfragen, Verfahrensweisen, Anwendungsfelder (pp.227-256). Heidelberg: Asanger.

Witzel, Andreas (1996). Auswertung problemzentrierter Interviews: Grundlagen und Erfahrungen. In Rainer Strobl & Andreas Böttger (Eds.), Wahre Geschichten? Zu Theorie und Praxis qualitativer Interviews (pp.49-76). Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Witzel, Andreas (2000). The problem-centered interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(1), Art. 22, http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/1-00/1-00witzel-e.htm [Access: September 17, 2007].

Witzel, Andreas (2001). Prospektion und Retrospektion im Lebenslauf. Ein Konzept zur Rekonstruktion berufs- und bildungsbiographischer Orientierungen und Handlungen. Zeitschrift für Sozialisationsforschung und Erziehungssoziologie, 21(4), 400-416.

Witzel, Andreas (2004). Archivierung qualitativer Interviews. Möglichkeiten für Re- und Sekundäranalysen in Forschung und Lehre. In Birgit Griese, Hedwig Rosa Griesehop & Martina Schiebel (Eds.), Perspektiven qualitativer Sozialforschung. Beiträge des 1. und 2. Bremer Workshops (pp.40-60). Werkstattberichte des Interuniversitären Netzwerks Biographie- und Lebensweltforschung (INBL): Universität Bremen.

Witzel, Andreas & Kühn, Thomas (1999). Berufsbiographische Gestaltungsmodi. Eine Typologie der Orientierungen und Handlungen beim Übergang in das Erwerbsleben. Reihe Arbeitspapiere des Sfb186, Nr.61, Universität Bremen, http://www.sfb186.uni-bremen.de/download/paper61.pdf [Access: September 17, 2007].

Witzel, Andreas & Kühn, Thomas (2000). Orientierungs- und Handlungsmuster beim Übergang in das Erwerbsleben. In Walter R. Heinz (Ed.), Übergänge. Individualisierung, Flexibilisierung und Institutionalisierung des Lebensverlaufs. 3. Beiheft 2000 der Zeitschrift für Soziologie der Erziehung und Sozialisation (ZSE), 9-29.

Irena MEDJEDOVIC, Dipl.-Psych., is research assistant at the Archive for Life Course Research at the University Bremen and is involved in establishing a national service infrastructure for archiving qualitative data. Her major research interests include the feasibility of archiving qualitative interview data and methodological issues of secondary qualitative data analysis.

Contact:

Irena Medjedović

Universität Bremen, Graduate School of Social Sciences (GSSS)

Archiv für Lebenslaufforschung

FVG-West, Wiener Straße/Ecke Celsiusstraße, Postfach 330 440

D-28334 Bremen, Germany

Tel.: +49 / (0)421 / 218 4169

Fax: +49 / (0)421 / 218 4153

E-Mail: irenam@gsss.uni-bremen.de

URL: http://www.lebenslaufarchiv.uni-bremen.de/

Andreas WITZEL, Dipl.-Psych., is director of the Archive for Life Course Research at the University Bremen. He is engaged in establishing a national service infrastructure for archiving qualitative data. His major research interests include qualitative methodology and methods, work socialisation, biography and the life course, especially the transition from school to work.

Contact:

Dr. Andreas Witzel

Universität Bremen, Graduate School of Social Sciences (GSSS)

Archiv für Lebenslaufforschung

FVG-West, Wiener Straße/Ecke Celsiusstraße, Postfach 330 440

D-28334 Bremen, Germany

Tel.: +49 421 218 4141

E-Mail: awitzel@gsss.uni-bremen.de

URL: http://www.lebenslaufarchiv.uni-bremen.de/

Medjedović, Irena & Witzel, Andreas (2007). Secondary Analysis of Interviews: Using Codes and Theoretical Concepts From the Primary Study [78 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(1), Art. 46, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0501462.