Volume 6, No. 1, Art. 19 – January 2005

Ethics in Research on Learning: Dialectics of Praxis and Praxeology

SungWon Hwang & Wolff-Michael Roth

Abstract: Qualitative social research designed to develop ways of understanding and explaining lived experience of human beings is a reflexive human endeavor. It is reflexive in that as researchers attempt to better understand their participants, they also come to better understand themselves. Consequently, research ethics itself becomes an ethical project, for it pertains to participant and researcher at the same time: Both are subjects, knower and known. Particularly in case of research on learning, reflexivity arises from the fact that the research itself constitutes learning about learning. How is ethics in research on learning reflexive of, in its praxis and praxeology, ongoing events and changes of the human learning? In this study, from our experience of conducting a project designed to inquire into "learning in unfamiliar environments," we develop pertinent ethical issues through a dialectical process—not unlike that used by G.W.F. HEGEL in Phenomenology of Spirit—grounded in our lived experience and developed in three theoretical claims concerning a praxeology of ethics. First, ethics is an ongoing historical event; second, ethics is based on the communicative praxis of material bodies; and third, ethics involves the creation of new communicative configurations. We conclude that ethics is grounded in a fundamental answerability of human beings for their actions, which requires communicative action that itself is a dialectical process in opening up possibilities for acting in an answerable manner.

Keywords: ethics, research on learning, dialectics, praxis, praxeology, communication, human body, reflexivity

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Ethics at Issue

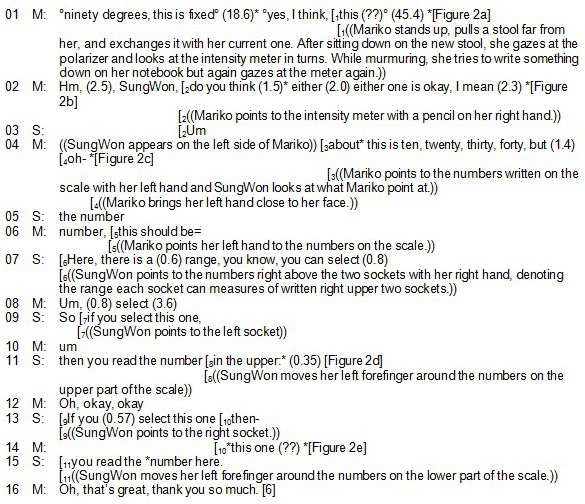

2.1 A moment in research on learning

2.2 Articulating the issue

3. Research Process

4. Dialectics in Ethics

4.1 Ethics as ongoing historical event

4.2 Ethics as communicative praxis of material bodies

4.3 Ethics in creating new configurations of communication

5. Toward Ethically Valuable Research on Learning

6. Coda

Fundamental to ethics in qualitative social research is the question about ways of understanding and explaining the lived experiences of human beings. Although it is quite recent to talk about research ethics at the institutional level (e.g., Tri-council Guidelines [PUBLIC WORKS AND GOVERNMENT SERVICES CANADA, 1998]), scholarly efforts in the social sciences to develop various qualitative research methodologies that approach human knowing and learning on their own in the complexities of everyday contexts (e.g., ethnomethodology [GARFINKEL, 1967]) have responded to the question in a wider sense. As salient in many social scientists' criticism of the artificial situations of the laboratory setting as a context for understanding human nature, positivistic approaches to human learning eliminate subjective self-experiences in the name of scientific objectivity and thereby produce knowledge incompatible with human subjectivity (e.g., GUBA & LINCOLN, 1989; HOLZKAMP, 1991): The human subject no longer exists either as the one we know about or the one who knows. Common to some qualitative approaches is the fact that any pursuit of scientific objectivity necessarily involves researchers' subjectivities and the very act of constructing an object changes the subjective ground for action that has enabled that action (e.g., BREUER, MRUCK, & ROTH, 2002; CHAIKLIN, 1993; NISSEN, 2003). Thus, particularly in research on learning, some researchers have not resigned to describing and interpreting their phenomena but proactively dealt with issues emerging from the mutually constitutive researcher | researched relationship. They thereby value research not only for producing knowledge but also for contributing to human development and improving the human condition (e.g., critical ethnography [ANDERSON, 1989], participatory action research [KYLE, 1997]). That is, such qualitative research does not abstract from the lived experience of researcher and researched—which, despite claims to the contrary, even many qualitative studies do in creating observational categories that the participants no longer understand (e.g., SMITH, 1999)—but inherently and continuously situates research and writing in the world we know through our experiences. Given that researchers' actions of inquiring into human learning changes the phenomenon—and thereby the researchers and their participants—two important aspects emerge concerning ethics in research on learning: first, the ethical value of research on learning is subject to a developing research praxis1) that respects developmental possibilities of both the participating learner and the researcher in their interactions; and, second, the value of ethics as a description of praxis is subject to the development of ethics theories (praxeology) that are reflexive of human experiences and events coming about in the course of the research process. [1]

How then is such an ethics be possible, an ethics that is reflexive of—in its praxis and praxeology—the ongoing events and the development of the human learning under study? In the most general terms, the issue of establishing reflexive theories—those that develop in accordance with changing realities while providing explanations of that order of the change—has been a focus of social studies (e.g., BLOOR, 2004; KUSCH, 2004). Particularly in research on learning, there have been attempts to organize mutually constituting relations of local events and theories through structural forms of research (e.g., activity theory [ENGESTRÖM, HAKKARAINEN, & HEDEGAARD, 1984], design experiment [BROWN, 1992], design-based research [KELLY, 2003]). In fact, these structural approaches have contributed to recognizing the importance of reflexivity in the developmental process of research. However, possibilities to achieve ethical theories in concrete research processes appear to have been developed by phenomenological sociologists, who elaborated a reflexive approach to human lived experiences and the lifeworlds from third-person and first-person perspectives (e.g., AGRE & HORSWILL, 1997; BERGER & LUCKMANN, 1966; LYOTARD, 1991; SCHUTZ & LUCKMANN, 1973). "Lifeworld" denotes the functionally patterned world that an organism perceives and acts in within some activity; it is a real world objectively given to and experienced by a person—we don't normally doubt the world surrounding us. In conducting research, an investigator might take a participant's lifeworld as an object of inquiry and analyze it from a third-person perspective; but in order to understand how the participant experiences that world the researcher should be able to take a first-person perspective of the participant's lived experiences as if they were her own. Of significant importance in this approach is the reflexivity involving different forms of research praxis (e.g., ROTH & BREUER, 2003; ROTH, 2004a): first, praxis acting on another's experience in reflexive to one's subjective experience (e.g., ethnomethodological reflexivity [LYNCH, 2000]), and second, "phenomenological reduction" of subjective assumptions embedded in the praxis (e.g., radical doubt, [BOURDIEU & WACQUANT, 1992]). In the case of research on learning, reflexivity arises from the fact that the research itself constitutes a process of learning about learning. Yet much research on learning objectifies the human subjects it studies, the people whose knowing and learning is of interest; and it disregards the fact that researchers are the knowing subjects and, as learners, unacknowledged objects of study. Concerning ethics, reflexivity implies that the way researchers develop and conduct data collection and analysis bears a relation to the way research participants are developing as part of their learning activities under study. It is at this point that we see possibilities for addressing ethics as praxis and praxeology, an ethics that develops through human social interactions in concrete situations. [2]

We are in the process of conducting a large-scale project designed to understand learning in and across different cultural environments ("navigating boundaries"). As part of the project, we developed a reflexive form of research on learning that inquires students' "unfamiliarity" with new and different learning environments. One of the research participants is an international female student (pseudonym Mariko) studying physics at a Canadian university. To gain a better understanding of the learning environment in the way it is salient and relevant to learner's everyday life, we conduct intensive ethnographic work where the first author participates in various learning activities of the participant and collects a wide range of data. Of particular concern in the fieldwork was the fact that not only the participant was learning physics in an unfamiliar environment but also the researcher (SungWon, visiting postdoctoral fellow from Korea) was conducting qualitative research in an unfamiliar environment and in that they both had multilingual and multicultural backgrounds. The reflexive relation between the two afforded two ethically important aspects during the fieldwork: on the one hand, it contributed to establishing a good rapport facilitating communication between SungWon and Mariko, and, on the other hand, it provided SungWon with a reflexive ground enabling to take a first-person perspective on Mariko's experiences refracted through the lens of her learning experiences. That is, the reflexive relation between "learning to do science" and "learning to do research" provided SungWon with opportunities to experience moments of research activities through an ethical (rather than cognitive) lens and bring the emerging ethical issues to bear on the research. Considering that ethical concerns are embedded in researchers' efforts to apply what they do and say in relation to their participants also to themselves, we see possibilities of ethically valuable research on learning in taking into account those moments and issues emerging from the lived experience of doing research. In the next section, we begin our study by introducing an exemplary issue with concrete case materials and articulating it through issue-based discussion. [3]

Research ethics concerns the endeavor of configuring a human relationship in which a researcher and a participant can respect their different grounds for actions during their overlapping and interweaving collective activities. The exact nature of the relationship between a researcher and her participant is different from case to case. In the case of research on learning, however, particularly when the participant is a young child or student—who is supposed to have less knowledge and power than the researcher (e.g., children [MAGUIRE, 2004])—the person's relationship to the researcher is quite different from other cases where the focus of inquiry is, for example, already demonstrated expertise (e.g., scientists, doctors, etc). In this section we articulate an ethical issue related to an asymmetry in knowing.2) As a way of developing the issue in sufficient complexity appropriate to the issue at hand, we first provide an episode depicting a moment at issue and a description of it, and introduce a reflexive narrative of the first author. We then develop the issues dialectically, that is, in a reflexive process. [4]

2.1 A moment in research on learning

The following episode occurred during a regular three-hour optics laboratory class, one of the physics undergraduate courses at the Canadian university where the study takes place. Mariko regularly attended the weekly class. The topic of her experiment on this day was "polarization" and included three subtasks: "The law of Malus," "Circular and elliptical polarization," and "Polarization due to reflection and Brewster's angle." The experiment was arranged in a small separate room apart from the usual bigger laboratory, because in case of polarization it was important to keep the room dark or the sensitive instruments would not have produced accurate measurements. At the beginning of the experiment, the instructor came to the classroom and gave instructions concerning the tasks and put various instruments on Mariko's lab bench. To conduct her first task (the law of Malus), Mariko was changing an angle between two linear polarizers (polarizer & analyzer) set in parallel between a light source and a sensor (Figure 1a) and measuring the intensity of a passing light by means of reading an intensity meter connected to the sensor (Figure 1b). [5]

Episode3)

Mariko rotates a handle attached to a polarization plate with her right hand and gazes the sensor and the light intensity meter by turns.

|

a)

|

b)

|

Figure 1: (a) Two linear polarizers (white arrows) are set in parallel between an unpolarized light source behind them and a sensor detecting a light passing through in front of them. In the experiment, the latter polarizer is called a polarizer and the former is an analyzer; (b) A light intensity meter is connected to the sensor. Seen on the scale is a fan-shaped graduation inscribed with two series of numbers, one above and one below. Two sockets (not seen in this picture) are found at the front bottom of the instrument. [7]

|

a)

|

b)

|

c)

|

d)

|

e)

|

Figure 2: (a) Mariko is changing the angle of analyzer relative to the polarizer; (b) Mariko is asking a question while pointing to the light intensity meter with a pencil on her right hand; (c) Mariko is pointing to the numbers on the scale with her left forefinger; (d) SungWon is pointing to the numbers written on the upper part of the scale with her left forefinger; (e) After mentioning the right socket, SungWon is pointing at the numbers written on the lower part of the scale with her forefinger. Mariko is pointing to the same end. [8]

Description

In this situation, Mariko was carrying out the first task; she fixed the polarizing angle of the analyzer to ninety degrees and thereby made its relative angle to the rear polarizer zero degree. She gazed at the sensor and turned to read the light intensity meter (turn 01). She attempted to write something on her notebook, but turned her head up to the meter again. She uttered "Hm" and pointed her pencil in the right hand to the light intensity meter (turn 02). She called and spoke to the researcher, who was recording the experiment at the corner of the room, "SungWon, do you think, either, either one is ok" (turn 02). As the researcher came up to the left side of the laboratory bench, Mariko pointed to the double structured scale using her pencil (see Figure 1b) and read aloud, "about this is ten, twenty, thirty, forty" (turn 04). She read until "forty" and then said "but." Instead of continuing, she kept silent for a while but for uttering an "oh," accompanied by a pointing gesture (turn 04). Her voice faded away, overpowered by the researcher's utterance "the number" (turn 05). Mariko repeated the word "number" and said "this should be" with her left forefinger pointing to the scale (turn 06). The researcher suggested, "Here, there is a range" and thereby cut off Mariko; she pointed to the labeled numbers written right above the two sockets, which denoted appropriate ranges of measurement (turn 07). As SungWon said "you can select" (turn 07), Mariko repeated "Um, select" and saw the researcher turning the two sockets (turn 08). After a pause, SungWon told Mariko "So if you select this one" (turn 09), "you read the number in the upper" (turn 11), thereby relating the left socket to the numbers on the upper line of the scale. Mariko responded, "Ok, ok, ok" (turn 12). While pointing to the other socket, SungWon continued saying "if you," which was followed by a pause and an utterance of "select this one" (turn 13). Mariko repeated, "this one" (turn 14). The researcher pointed to the lower line of numbers on the scale and said "you read the number here" (turn 15). Mariko responded "Oh, that's great, thank you so much" and thereby closed the conversation (turn 16). SungWon moved away, and Mariko looked at the meter by herself. [9]

SungWon's Narrative

The lab instructor came to Mariko and explained what to do with the instruments and equipment. In the same room, I was recording the entire process with an 8-millimeter camcorder, including their conversation. Once the instructor had moved away to take care of other students in another laboratory, Mariko began her first task. She looked carefully at lab manuals and instruments on the lab bench, particularly the different parts of a light intensity meter including the sockets on the front bottom and its scale. She turned to me and asked, "do you think either one is ok?" The instrument seemed to have confused her about how to select and what is a relevant socket in this task. She was asking me for help. I knew that selecting a relevant socket in this kind of instrument could be a confusing moment for a person who uses the instrument for the first time—I had similar experiences while studying physics and saw students have difficulties while teaching at the secondary school level. Nevertheless, at this moment I hesitated for a while, attending to a fleeting thought whether it would be appropriate for me to participate in her experiment by giving assistance. I do not remember exactly what I was concerned about at that moment, but perhaps I was feeling a kind of conflict concerning what would be a relevant action as a researcher. Even before I had sufficient time to mull it over, I found myself moving toward Mariko's laboratory bench and explaining to her why there are two sockets on the meter and how each one corresponds to the two series of numbers on the scale. I returned to the camcorder and continued monitoring the recording. Almost at the end of the first task, Mariko appeared dissatisfied with the measurements she had recorded. She left the room searching for the lab instructor and returned with him. Soon, they figured out that she had not calibrated the light intensity meter and Mariko decided to repeat the first task with a calibrated meter. This situation reminded me of the previous situation where I felt torn: would it have been better if I had helped her more carefully? At the same time I doubted: it would not have been the relevant action for me—researcher and physics expert—to assist a student in her task. Preoccupied with the research process, I began to attend to other than my ethical doubts. Almost at the end of the three-hour experiment, a worse situation occurred. I found that Mariko had not finished the three tasks within the given time and she felt bad about it. I was reminded again of the events at the beginning of the session. I began to feel responsible: I had refrained from helping her and now she had not finished the experiment within the allotted amount of time. What should I have done when she asked me for assistance? [10]

In the previous section, the immediate issue raised in SungWon's narrative was whether a researcher has a responsibility to assist a student research participant when the latter asked for help, and to what extent, if at all, she had an ethical obligation to assist. As pointed out before, this kind of situation is not rare in qualitative research on learning where researchers already are knowledgeable practitioners regarding the topics and skills that the students in the study are supposed to learn. It goes without saying that being or becoming competent in the practice under research is important to develop a first-person understanding of the situation. However, without a reflexive step to overcome the pre-understandings a researcher brings to a phenomenon, the first-person understanding is far from producing relevant knowledge (e.g., ROTH, 2004a). In this section, as a step toward a reflexive understanding research ethics, we engage and elaborate a series of issues. [11]

One ethical question emerging from the situation might be, "What do I (researcher) do when I am more competent at the practice than my research participant?" In a different context, the second author (Wolff-Michael ROTH) and his collaborators have chosen a radical response—the process of research must be, in the first instance, of benefit to the teachers and students involved (e.g., ROTH, LAWLESS, & TOBIN, 2000; ROTH & TOBIN, 2004). However, to respond to the question here we ask ourselves a reflexive question, "What presupposition does this questioning involve?" The presupposition might have been, "Is it worthwhile for the researcher, as a person who collects data, to participate in a learning activity that she wanted to understand?," which raises concerns about the quality of data. Or it might have concerned about the participant's learning, "Would the researcher's action be really helpful as she have intended? Wouldn't it make the participant dependent on the researcher?" In any case, the questioning seems to presuppose that there is something incompatible between the researcher's activities of conducting research and the participant's activities of learning science to a certain extent and it looks so indeed. The critical moment must have arisen from the fact that Mariko's learning activity took place in the context of the research. Thus, in the optics experiment Mariko's every move is not only an act toward learning science but also a contribution to the research; in the same way, the researcher's every move is not only an act of carrying out the research but also mediates the participant's learning. The two activities occur simultaneously in the same setting and unfold through interactions between researcher and participant. [12]

It is important to note that this kind of situation occurred at the beginning of data collection but disappeared later. Although the researcher and the participant have never had a conversation about the event (i.e. which SungWon might try to have the next time in such a situation) or about the rule (i.e. how to act subsequent to similar situations), Mariko never again asked SungWon to help in the laboratory tasks, and SungWon did not to try to assist Mariko by getting involved. The critical moment occurred as both had learned at this moment how to act toward and respect the other. Therefore, we come to ask if there could be an answer to the initial question, or, in other words, if it was a relevant question. We propose that a relevant ethical question drawn from the episode should be about a moment situated in the historical change of praxis, that is, "How do the researcher and the participant experience contradictory situations and learn to act with respect to one another?" In what follows, we develop a response to this question by working through an analysis of the episode, which leads us to make three claims about ethics. The historical change of collective praxis emerges not only over a long period of time, which is discerned retrospectively, but also in the short term, which is in the present progress tense. We can see it in various manifestations that human bodies produce in and for communication. We articulate the associated microprocesses in the fourth section. [13]

In this contribution we articulate aspects salient in our praxis of research on learning and thereby develop a praxeology of ethically valuable learning research from a dialectical perspective. In terms of dialectics, we note that research praxis and talk of it develop in the course of being reflexive of ongoing events and changes of human lived experiences (e.g., IL'ENKOV, 1982; ROTH & TOBIN, 2002). In the previous section, we saw a moment that one researcher had experienced with the research participant (episode), which brought forth an ethically critical question for the researcher herself. The moment became a constituting event in her learning to do research and in research on learning. This was a first reflexive step that transformed lived experience into the description of the lifeworld. In the next step, we provided a description of the issue having changed as we discussed it in a reflexive fashion, that is, reflexive to the process of raising and phrasing the question. In this sense, our study constitutes a dialectical process in which our understanding of ethics evolved: each step constituted research praxis producing a description of ethics (praxeology of ethics) and, by the very praxis, became a ground of reflexive step.4) As we see in the next section, the articulated issue in the previous section becomes a new ground for understanding the event; we articulate how ethics in the making unfolds through interactions of the researcher and the participant. Required for this work are analytic tools for understanding concrete data. [14]

This study is a part of a larger project designed to understand how people learn and develop cultural practices particularly related to science and mathematics when they move across different settings. The research participant is an international female student who came from Japan to Canada for her undergraduate study. To gain a better understanding of learning environment as is salient and relevant to learner's everyday life, we conducted extensive ethnographic work following Mariko's different learning activities. We video recorded and collected materials used in curricular classroom activities (lectures and lab experiments), problem solving activities (assignments) on her own or with her classmates, and non-curricular activities such as participating in interesting sessions of her or other departmental colloquia. We also planned and recorded meetings with participants, talking about any issues salient to and initiated by either the researcher or the participant. Every activity was documented in the fieldnotes in day-by-day fashion and thereby constituted a large database together with video tapes and other paper materials. [15]

Both authors viewed the videotapes and documents repeatedly, both individually and collectively, with the intent to come to a better understanding of Mariko's learning activities and her interactions with people such as a researcher, a classmate, and an instructor. Our analysis was informed by the method of Interaction Analysis (JORDAN & HENDERSON, 1995) and analytic methods of discursive psychology (EDWARDS & POTTER, 1992). We considered not only explicit discursive actions but also non-verbal interactions as available resources for understanding communication (e.g., HEIZMANN, 2003). In our individual and collective analysis sessions, we formed initial hypotheses that we sought to confirm or disconfirm in subsequent analyses or by running them by one another. Our results emerged from repeated cycles of generating, refining, and discarding working hypotheses. In the process, we generated written analyses of different episodes across the database. [16]

In this section, we analyze the interactions between the researcher and the participant at the microlevel and thereby elaborate our descriptions of the ethical aspects of research praxis and associated theoretical claims for ethics from a dialectical perspective. [17]

4.1 Ethics as ongoing historical event

In understanding the episode, one may say that the situation is simple and involves nothing important; the student asked a question concerning her instrumentation of the light intensity meter and in response to it SungWon went to the laboratory bench and told her how to read the scale. But, in her narrative the researcher described that she felt a conflict when she was asked a question, and responsibility when she came to know that Mariko's had used the meter without calibration and had to repeat the task, which subsequently resulted in not completing the task within the three-hour laboratory. Why did SungWon have to feel the conflict with and the responsibility for her action of attempting to assist her? This conflict itself is an indication that the issue was salient, because it has arisen in the research process, and, in its very possibility as a form of being, is also a possibility to other researchers. Here, the issue is not "what the action does in doing so" but its relation "to what it brings into effect," which unfolds temporally. Whereas the former is the present, the latter is the future; or, whereas the latter is the present, the former is the past. Produced in this relation is the fundamental uncertainty in ascribing the latter to the former and its agent, because a person always acts without knowing what is coming up in a future tense (ROTH & MIDDLETON, 2004). Therefore, people, when they look back on their past actions, often make seemingly different statements. The researcher in the narrative might say later on "It should have been done differently" but at the same time argue that "It couldn't be otherwise." [18]

An action takes place in specific social and material settings, which provide a range of possibilities for action. In its unfolding, an action always concretely realizes one of potentially many possibilities; at the same time, all other possibilities remain unrealized. What was left out constitutes a background of action, that is, what was not salient "in doing so." However, an effect of an action and its ascription arises not only from what is enacted but also from the background because they both constitute "what an action does in doing so." Other possibilities might become salient after the forthcoming situation had changed the ground of ascribing act. Thus, descriptions that involve ethical evaluations such as "it would have been better if SungWon had checked the instrument calibration or if she had advised Mariko to ask the lab instructor" are possible only after we know that Mariko had to repeat her task and therefore could not finish it in time. The possibilities were not salient beforehand because SungWon now has a different interpretive horizon, one that historically evolved after the events. SungWon could not "recognize" the ethical dimension because time flows from past to present, not from present to past, and future episodes are emergent rather than determined by a determinate present.5)[19]

SungWon's action of attempting to assist Mariko does not determine the forthcoming action nor is it completely unrelated to it. The relation between consecutive moments is always incomplete and changeable. There seems to be a gap between SungWon's concern for Mariko and the forthcoming situation, that is, between what an action does in doing so and what is ascribed to it as having brought about. A note of care is appropriate here. The gap becomes an issue only when we consider it in the world of possibilities. Despite the uncertainty, researcher and participant interacted and communicated with one another and thereby continuously reconstituted their grounds for actions. Two implications emerge from this. First, researcher and participant interact by means of resources available "here and now" and salient to themselves. Second, both can see new possibilities only when they do something and thereby come to stand on a new ground for action, which has been changed by the previous action. Thus, the gap does not exist because they respect their lived experiences. They actually know how things had to occur in that way, before talking about whether what they had actually done was right or wrong. [20]

Therefore, fundamental to our first claim for a praxeology of ethics is the historical structure of actions:

Claim 1

Ethics does not exist as something independent of but only in the form of relations under specific circumstances of human activities. It arises from the temporal relation of (a) what an action does in doing so and (b) what is ascribed to it as bringing into effect. However, the action itself changes the ground of ascription and thereby the description of the action (discontinuity between the possibility for acting in some way and the factuality after having acted). This makes for a continuous process of development, which is open to historically new forms of praxis and subject relations. [21]

Research ethics arises in the endeavor of developing human ways of inquiring into human beings—researchers who reduce human beings to blips in correlation graphs, outliers, and aggregates do not face ethical issues in this way. Ethics is an aspect of social practice, enacted by a researcher as a subject, which affects and changes the lived-in world rather than being a move in a world of discourse (ROTH, 2004b). Even the situation where a researcher or participant raises and considers ethical issues occurs in a specific social and material situation (see Section 1.1 & 1.2). Our goal is to do research that recognizes that the social comes into being in and through the doing of actual people (researcher, participant) under definite conditions not all aspects of which are under our control. This is a stance that opposes postmodern discourse, which has abstracted knowledge from the lives of people, and in which the subject (researcher and participant) exist only as characters in plots (SMITH, 1999). What therefore really matters in ethics is to understand "how each interaction between a researcher and a participant constitutes a configuration of humanness." That is, the issues arising from our first narrative cannot be understood without also analyzing the concrete interactions between researcher (SungWon) and participant (Mariko). Of particular importance in this approach is the role of our bodies, because these are the very tools by means of which we articulate and make ourselves available to and for others (ROTH, 2005b). One of the ways in which we communicate is by means of the prosodic features of the voice, which modulate and mediate the words that others extract from the sounds we produce (ROTH, 2005a). In the following, we use the analysis of prosodic features to elaborate what we can learn from the transcribed episode. [22]

4.2 Ethics as communicative praxis of material bodies

In the episode, Mariko was setting up instruments to conduct her first task while muttering some words in a low voice (turn 01). She fixed an angle between the polarizer and the analyzer at zero degree and gazed at the light intensity meter. Her right hand was ready for recording a measurement. She looked at her laboratory notes where she had drawn a table to be filled with a series of intensity measurements and repeatedly attempted to write something at the first line of the table. However, instead of recording a measurement, she said "Hm" and starred at the light meter again (turn 02). The steeply falling pitch contour in her voice (see Figure 3a) and her hesitating hand movements manifested uncertainty and insecurity. With and through her body, she was making her experience available to SungWon. Soon, her right hand pointed the pencil toward the light intensity meter that she was gazing at, thereby indicated that the issue was in the meter (turn 02). She called SungWon and continued speaking, "SungWon, do you think" (turn 02). Here, Mariko bodily produced an utterance in which the pitch contour had a structure of asking the other's response and therefore an action having more communicative feature than her previous actions (see Figure 3a).6) It did so actually. The researcher responded to Mariko's calling with a short "Um" (turn 03) and began to move from the place where she set up her camcorder directed toward Mariko's laboratory bench. Mariko moved her pencil right and left along the bottom of the scale without saying anything (see Figure 1b & 2b). After the 1.5 seconds pause, Mariko said "either" (turn 02) and thereby explicated that the issue was related to some alternatives in the light meter, but stopped her utterance again. She moved her pencil to the right side of the scale during two seconds and then said "either one is ok" (turn 02). Here, she seemed to complete her questioning but immediately she made an additional remark, "I mean," with a long flat pitch line (see Figure 3b). The action produced an opportunity for something to follow and what followed actually was a pause of 2.3 seconds. In the meanwhile, the researcher almost had arrived at the laboratory bench. As soon as SungWon appeared on Mariko's left side, the latter continued speaking, "about this is ten, twenty, thirty, forty" (turn 04). Mariko read aloud the numbers while pointing to them using her left hand. Now she articulated with and through her body what to see on the scale in relation to her issue in more elaborated speech and gesture. Furthermore, she bodily produced another opportunity to articulate it more, rather than completing it there, by saying "but" with a high pitch compared to a declining pitch contour preceding it (see Figure 3c).

a)

b)

c)

Figure 3: (a) In our analysis, Mariko was found to make the "hm" sound frequently in different pitch contours. In this talk,

"Hm" is close to a sigh of unpleasantness. The second part, "do you think," has a pitch contour that makes it as a questioning

sentence requiring an object; (b) the pitch of "either" extends a little while at its end and thereby lets the following long

pause unsurprising. The second part, "either one is ok" has a pitch structure of a complete questioning, but the subsequent

talk, "I mean," at a same pitch for about 0.5 second makes the sentence incomplete again; and (c) the gradually decreasing

pitch rises abruptly at the end, thereby makes the whole talk uncertain. [23]

In this situation, Mariko was articulating what she perceived as problematic by elaborating structures in speech and gesture in and through her body. Mariko opened by saying "do you think," but the object of "think" was not clear from the beginning. Rather, it developed as her communicative actions unfolded, from "either" to "either one is okay, I mean," and again "about this is ten twenty thirty forty but," involving pauses between them. At the same time, Mariko's gestures in and between talks had changed. At first, she just pointed the light intensity meter (Figure 2b), but she made a next movement of the pencil along the bottom of the scale. Then she pointed the pencil to the right side of the scale and finally even came to use the other hand to point a series of numbers (Figure 2c). Whereas she had began producing an utterance that could be heard as a question, she actually co-articulated the situation by and for herself in a communicative form; she did not interrogate SungWon. The elaboration became available to the latter (and her camcorder) because Mariko made communication materially available in the situation. In the three utterances and between pauses, we see their ending pitches constitute contrasting structures to preceding pitch contour in forms of a low (first), flat (second), and high (third) shape (see Figure 3). Incomplete endings existed not only in the grammatical structure (what was said) but also in the physical structure (how it was said), which thereby produced uncertainty (ROTH & MIDDLETON, 2004). [24]

The communication provided flexibility not only to the speaker herself (Mariko) but also to SungWon who was coping with her question. Mariko physically produced time for the researcher to go to the laboratory bench to see what Mariko referred in terms of "either" and what she was pointing, and again the researcher's response allowed time for Mariko to articulate her issue. Although the video does not show how SungWon moved to the laboratory bench and therefore what kind of interactions occurred between the two in the meantime, there is some evidence that Mariko had attended to the researcher's movement. Only after a long pause Mariko made, she uttered "about this is"; it was immediately after SungWon had come to her left side. Mariko did not look at SungWon directly but was aware of the other's moving toward her. Mariko acted in consideration of the time required for SungWon to arrive next to her. SungWon did not talk while she was moving but took a relevant position and timing in her communication with Mariko. Throughout these different modes of communication, the two were articulating the unfolding situation collectively. All the manifestations that their bodies produced (e.g., high pitch talk, pause, gesture, etc.) constituted resources for constructing relevant responses to one another. In this sense, we see Mariko's initial actions constituted more like a request to the researcher of participating in her thinking and the two persons' communication constituted a process of collective elaboration rather than a mechanical process one asked a question and the other was supposed to give an answer to it. [25]

Therefore, the role of human bodies in communication is the central and fundamental element in our second claim for a praxeology of ethics:

Claim 2

Central to ethics is the role of human bodies that consume the (illocutionary) act and at the same time produce the (perlocutionary) act, thereby making an ethical commitment to and having ethical responsibility for the action. Ethics is therefore distributed over acting human bodies in the communication that constitutes the phenomenon both cognitive and emotional. [26]

Ethics matters for human bodies and actions they execute are interpreted in terms of intentions; attributing an action to an individual (an agent) differentiates self from other (JEANNEROD, 1999). Central in this phenomenon of perlocution7) is the circulation of the act that human bodies produce and consume in interaction. The communicative action constitutes one's bodily act responding to another's actions salient to the acting body itself. In the process of responding, the body acts on an illocutionary aspect of the action and consumes it, whereby the body produces a new aspect of the action which goes beyond its illocutionary aspect (perlocution). Here, what is cognitively and emotionally achieved with respect to what had been intended implies an ethical commitment to or responsibility for the action. The acting human bodies manifest commitment in the process of production and consumption through its structured features (e.g., speech, gesture), thereby constituting a configuration of humanness such as concern for one another. Ethics, in this sense, is distributed over human bodies involved in and coproducing communication (BAKHTIN, 1993; RICŒUR, 1992). [27]

4.3 Ethics in creating new configurations of communication

In the first part of the episode, Mariko articulated her issue in more elaborate forms in the process of speaking to the researcher who in the meanwhile could have come to the laboratory bench in response to the action (turn 01-04). In the next situation, the researcher was looking at the light meter while standing on the left side of Mariko. After her utterance "about this is ten, twenty, thirty, forty, but" and pointing gestures, Mariko was quiet. All of sudden, she said "oh" as if she had come to see something she had not done. Mariko's subsequent utterances quickly came about, but the researcher's louder voice "the number" overlapped it almost at the same time (turn 05). From a communicative perspective, SungWon's utterance articulated that the current issue was related to the numbers on the scale by rephrasing Mariko's speech and gestures in terms of "the number." The researcher's action was consuming what Mariko may want to indicate in her action (illocution) and thereby producing an effect of collective understanding. In as far as Mariko wanted to speak to the researcher about her concern, researcher's response explicated what had been achieved. In response to the utterance, Mariko repeated "number" and continued to say "this should be" while pointing her left hand to a specific part of the scale (turn 06). In doing so, Mariko consumed the researcher's previous utterance directly and made it of a ground for next action. [28]

Intended or not, the researcher's utterance "the number" had cut off Mariko who at first did not continue after uttering "oh." Mariko could have disregarded it and continued her talk when the researcher had finished her utterance. Instead, she repeated saying "number." She said it as if speaking to herself or put differently, as if she did not care who uttered which word. She moved on to say "this should be" (turn 06). Mariko's action produced a configuration of interaction having a feature of collaboration cognitively and emotionally. A similar situation occurred in the next turn. Mariko was attempting to articulate the issue, but the researcher's saying "here" cut off Mariko (turn 07). SungWon pointed to the bottom of the light intensity meter, where some numbers were written right above the two sockets, that is, the required information to know how to read the complex structure of the scale—the scale had one fan-shaped graduation but two series of numbers above and below it, which to use between them depended on which socket to use for connecting the meter to the sensor. SungWon said, "there is a range, you know, you can select" (turn 07). This time again, Mariko did not insist on continuing her previous talk; instead, she said "Um, select" (turn 08). [29]

Throughout the interaction, the two articulated more clearly that the issue concerned "the numbers" on the scale and what to "select." In this situation, SungWon's actions were more like those of a person participating in collaborative thinking, but at the same time SungWon was a researcher, not a student who conducted the experiment. She said, "you can select" and by repeating "select" Mariko had a turn at figuring things out for herself. She looked at the meter for quite a long time without saying anything (turn 08). After a while, SungWon broke the silence and began to talk about how the left socket would be related to the numbers on the scale (turns 09-11). That SungWon spoke first implies that she understood Mariko's inaction as an expression that Mariko had not come to a clear understanding and needed to know more. In other words, Mariko's pause was achieved as an expression of an unclear understanding by the SungWon's action, and SungWon, in doing so, made her concern available for Mariko to see. The concern was achieved again when Mariko said "um" (turn 10) in response to the SungWon's "So if you select this one" (turn 09). If we were to see in SungWon's action of ending a pause as an attempt to be responsible for the situation, we may find one of its material grounds in the fact that Mariko produced her utterance ("select") by consuming the researcher's utterance ("you can select"). [30]

Mariko's pause led the situation to the SungWon's action of elaborating the sense of her "you can select." Whatever SungWon intended by saying "you can select," in saying so she was giving Mariko leeway to act rather than requesting a specific action. In response, Mariko paused, which in turn gave SungWon leeway to act. In both cases, the two did not force specific actions onto one another and therefore left open with respect to what and how to do next. The uncertainties involved in the actions allowed SungWon and Mariko opportunities to produce relevant acts that respected the other, thereby materializing their mutual care. [31]

Therefore, we propose in our third claim to take into account the development of ethics from a communicative perspective:

Claim 3

A communicative act involves greater ethical value with respect to one another when it provides more opportunities for consuming another's acts. This gives all parties leeway to act on their own grounds and thereby constitutes a process of producing new forms of configuration of humanness. [32]

In the episode Mariko spoke to the researcher by the questioning sentence, "do you know" (turn 02). Given her education and teaching experience, SungWon was the more knowledgeable relative to the instrumentation; the episode shows that knowledgeability is a matter of communicative interaction at concrete situation. We saw that Mariko's actions of pause (turn 08) and an utterance (turn 09) had allowed the researcher to articulate her knowledgeability for the other. The researcher's action could become a manifestation of her knowledgeability in so far as it was a relevant and acceptable action in communication. After Mariko said "Oh, okay, okay," SungWon began to talk about the right socket. In this situation, however, interactions between the two were quite different from those of the previous situation in which the researcher had talked about the left socket (turns 09-12). SungWon began by uttering "if you" while pointing the right socket; but she paused for 0.57 second before continuing, "select this one." Mariko's response was also different. As SungWon said "this one" (turn 13), Mariko repeated "this one" and her hand had already pointed to the lower series of numbers on the scale (see Figure 2e). SungWon's pause became a resource for Mariko to articulate her own knowledgeability for the other. In Mariko's gesture, SungWon's action achieved a concern for the other who might have already realized what would be talked and therefore might not needed more explanation. [33]

In summary, the episode did not involve a mechanical, determinate process of asking, giving, and receiving information. Researcher and participant collectively articulated and figured out the relevant issues at hand, which nevertheless had to unfold relevantly to one another in that they were communicating on different grounds. We consider every act as a manifestation of the way the other's act is consumed and reproduced on a new ground. Every act with respect to the other constitutes an ethical configuration. Therefore, the issue is not what is asked and answered but how it is asked and answered. [34]

5. Toward Ethically Valuable Research on Learning

We began this study with the intention of developing an ethics for research on learning that is reflexive of the lived experiences and events coming about in the course of doing research. In response to it, we first presented a moment of research on learning that was perceived as ethically critical (from a researcher's perspective) and articulated an initial issue into a dialectical question through a series of reflexive discussion. The initial question of "whether the researcher had to assist the participant's experiment" changed into "how the researcher and the participant experienced the situation collectively and learned to act with respect to the other." In the next step, the issue changed to the description of the event itself, particularly at the level of microanalysis; finally, we elaborated more extensive theoretical claims of ethics. Throughout the study, we articulated different ways of talking "ethics in research on learning" that ranged from an ethically critical moment that required more than following rules (e.g., GUILLEMIN & GILLAM, 2004) to a moment that was not critical. We exemplified that those different praxeologies were not only embedded in a praxis at different levels of reflexivity (e.g., WOOLGAR, 1988) but also constitute themselves as a reflexive praxis that concretely realize possibilities inherent in lived experiences, that is, dialectical reflexivity (HEGEL, 1977). At this point, we ask "what is our ethics in the dialectical development of our study?" We respond to the question in terms of a following discussion toward ethically valuable learning research. [35]

Ethical research on learning is a matter of praxis and at the same time a matter of reflexive understanding of this praxis. Doing research, becoming part of participants' lifeworlds, means that researchers are conditioned by and therefore should deal with problematic situations as the participants experience them. Researchers cannot be direct problem solvers in and of those situations; but it is also true that they are not independent of the problems because they are also subjects in the same world. Doing research for us is a process of collectively overcoming the problematic situations together with the participants, and at the same time producing knowledge that goes beyond localities of immediate and subjective experience. Despite the uncertain relations between events and theories, researchers can talk about learning phenomena because of their bodies, that is, their bodies enable them to experience and reflect. It is in recognizing the intersubjectivity of researcher and participant, who in their joint ongoing and concerted engagement constitute the research activity that we come to enact an ethical ethics rather than a political ethics that pretends to be unpolitical (e.g., ROTH, 2004c). [36]

Research on learning involves many facets including the learner's tasks, the researcher's participation, talking about the participation, and looking back on the talk. But accounts do not constitute lived experiences of doing research; the thrownness of first hand experience is an irreducible and non-reproducible phenomenal field (e.g., MÜLLER, 1972; VARELA, 1996). Despite complexities researchers do research for they can create new configurations of praxis having different qualities than any one before. Emerging praxis of different qualities comes with a reconfiguration of human bodies accompanying the evolution of communication (e.g., ROTH, 1999), which people may call "becoming a researcher." Here, becoming is not a movement from existing as one to existing as another, but is the creation of some other that affirms both of them and at the same time leads to negations ultimately as dialectical continuation (e.g., GLASSMAN, 2000). [37]

In this study we explicated the dialectical processes involved as an ethical issue came about and disappeared. That is, it became possible to take another look at the phenomenon (e.g., PLESSNER, 1978) as human subjects concretely produced the activity with and through their bodies, which we conceptualized as dialectics of praxis and praxeology. Our study constitutes an ethical process of figuring out an ethical issue in that it was open to the developmental possibilities that emerged in the process. In research on learning, a researcher's ethical answerability not only with respect to another but also with respect to herself lies in the opening up of possibilities to act in an answerable manner. It is the answerability mediated by uncertainty and the equity established in one's own relevant ground for action. [38]

Ethics in research on learning is a reflexive endeavor to establish a configuration of researcher-participant interaction beneficial to the development of a participant's learning activities within research activities. This study shows that ethics develops as researchers concretize ethical aspects of their lived experiences in research activities, which realize ethical possibilities in those experiences and constitutes itself as a new configuration of praxis of ethics. That is, the dialectics of praxis and praxeology constitute the heart of a reflexive development of ethics. [39]

This work was supported by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. We are grateful to our research participant for her contributions to this project.

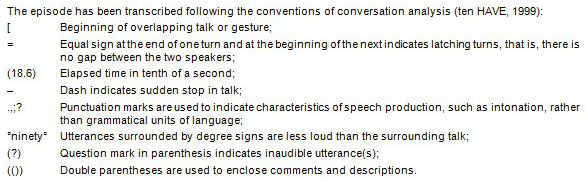

Conventions of conversation analysis (ten HAVE, 1999)

1) Concerning the relation between theory and practice, or lived experience and hermeneutic experience, we prefer to say "praxis" to denote "its precedence to the theory that is used to describe and explain it" and also "praxeology" to denote "talk about or explanations of praxis, grounded in and developed out of praxis" (ROTH, 2002, pp.155-174; ROTH, LAWLESS, & TOBIN, 2000). <back>

2) The issue of who knows what during an interview can be very complex and therefore ought to be an empirical issue rather than be taken for granted. Thus, in study concerning the interviews students conducted with expert scientists, who knew what was continuously contested such that at times even an undergraduate students came to be recognized as knowing more about graphs and graphing than a professor in his department (ROTH & MIDDLETON, 2004). <back>

3) The episode has been transcribed following the conventions of conversation analysis (ten HAVE, 1999); see Appendix. <back>

4) This is the process G.W.F. HEGEL (1977) used in Phenomenology of Spirit, where the outcome of the study is an understanding of the process of arriving at the outcome. Consciousness comes to understand itself as an instance (concrete realization) of collective but contingent consciousness, which means that the process of arriving at this understanding is itself contingent. <back>

5) This, from our perspective, is the fundamental problem in much of public life in the attribution of responsibilities for events that were not and could not be foreseen. "Monday morning football" and Whig history are not good models for science. <back>

6) There is no other way to communicate than with and through the body. We specially mark the bodily nature of the production, for even most qualitative research writes the body out of its accounts and features talk as disembodied discourse only (SMITH, 1990). <back>

7) Locution, illocution, and perlocution are terms used in speech act theory, each of which denotes "performance of an act of saying something" (locution), "performance of an act in saying something," and "performance of an act producing some consequential effects" (AUSTIN, 1962, emphases in original). In this study, we use the framework not only for speech act but also for any human act when it comes to ethics because it is of no use to say ethics without human communication or the communicative aspect of human action. <back>

Aderson, Gary L. (1989). Critical ethnography in education: origins, current status, and new directions. Review of Educational Research, 59, 249-270.

Agre, Philip & Horswill, Ian (1997). Lifeworld analysis. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 6, 111-145.

Austin, John, L. (1962). How to do things with words. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. (1993). Toward a philosophy of the act. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Berger, Peter L. & Luckmann, Thomas (1966). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. New York: Doubleday & Company.

Bloor, David (2004). Institutions and rule-scepticism: A reply to Martin Kusch. Social Studies of Science, 34, 593-601.

Bourdieu, Pierre & Wacquant, Loïc J. D. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Breuer, Franz; Mruck, Katja & Roth, Wolff-Michael (2002). Subjectivity and reflexivity: An introduction [10 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal], 3(3). Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-02/3-02hrsg-e.htm. (Accessed November 17, 2004).

Brown, Ann L. (1992). Design experiments: Theoretical and methodological challenges in creating complex interventions in classroom settings. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 2, 141-178.

Chaiklin, Seth (1993). Understanding the social scientific practice of Understanding practice. In Seth Chaiklin & Jean Lave (Eds.), Understanding practice: perspectives on activity and context (pp.377-401). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Edwards, David & Potter, Jonathan (1992). Discursive psychology. London: Sage.

Engeström, Yrjö; Hakkarainen, Pentti & Hedegaard, Mariane (1984). On the methodological basis of research in teaching and learning. In Mariane Hedegaard, Pentti Hakkarainen, & Yrjö Engeström (Eds.), Learning and teaching on a scientific basis: Methodological and epistemological aspects of the activity theory of learning and teaching (pp.119-189). Aarhus: Aarhus Universitet Psykologisk Institut.

Garfinkel, Harold (1967). Studies in ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Glassman, Michael (2000). Negation through history: dialectics and human development. New Ideas in Psychology, 18, 1-22.

Guba, Egon G. & Lincoln, Yvonna S. (1989). Fourth generation evaluation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Guillemin, Marilys & Gillam, Lynn (2004). Ethics, reflexivity, and "ethically important moments" in research. Qualitative Inquiry, 10, 261-280.

Hegel, Georg W. F. (1977). Phenomenology of spirit (Translated by A. V. Miller). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heizmann, Silvia (2003). "Because of you I am invalid!"—Some methodological reflections about the limitations of collecting and interpreting verbal data and the attempt to win new insights by applying the epistemological potential of ethnopsychoanalytical concepts [79 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal], 4(2). Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/2-03/2-03heizmann-d.htm (Accessed November 17, 2004).

Holzkamp, Klaus (1991). Experience of self and scientific objectivity. In Charles W. Tolman & Wolfgang Maiers (Eds.), Critical psychology: Contributions to an historical science of the subject (pp.65-80). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Il'enkov, Evald V. (1982). Leninist dialectics and the metaphysics of positivism. London: New Park Publications.

Jeannerod, Marc (1999). To act or not to act: Perspectives on the representation of actions. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 52A, 1-29.

Jordan, Brigitte & Henderson, Austin (1995). Interaction analysis: Foundations and practice. Journal of the Learning Science, 4, 39-103.

Kelly, Anthony E. (2003). Theme issue: The role of design in educational research. Educational Researcher, 32(1), 3-4.

Kusch, Martin (2004). Rule-scepticism and the sociology of scientific knowledge: The Bloor-Lynch debate revisited. Social Studies of Science, 34, 571-591.

Kyle, William C. Jr. (1997). Action research. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 34, 669-671.

Lynch, Michael (2000). Against reflexivity as an academic virtue and source of privileged knowledge. Theory, Culture, & Society, 17(3), 26-54.

Lyotard, Jean-François (1991). Phenomenology (Translated by Brian Beakley). Albany: State University of New York Press.

Maguire, Mary H. (2004). What if You Talked to Me? I Could Be Interesting! Ethical Research Considerations in Engaging with Bilingual / Multilingual Child Participants in Human Inquiry [39 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal], 6(1), Art. 4. Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/1-05/05-1-4-e.htm (Accessed November 17, 2004).

Müller, A.M. Klaus (1972). Die präparierte Zeit: Der Mensch in der Krise seiner eigenen Zielsetzung. Stuttgart, Germany: Radius Verlag.

Nissen, Morten (2003). Objective subjectification: The antimethod of social work. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 10, 332-349.

Plessner, Helmuth (1978). With different eyes. In Thomas Luckmann (Ed.), Phenomenology and sociology (pp.25-41). Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Public Works and Government Services Canada (1998). Tri-council policy statement: Ethical conduct for research involving humans. Ottawa: Author.

Ricœur, Paul (1992). Oneself as another. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Roth, Wolff-Michael (1999). The evolution of Umwelt and communication. Cybernetics & Human Knowing, 6, 5-23.

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2002). Being and becoming in the classroom. Ablex/Greenwood.

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2004a). Cognitive phenomenology: Marriage of phenomenology and cognitive science [45 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/ Forum Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal], 5(3), Art. 12. Available at: http://qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-04/04-3-12-e.htm (Accessed November 17, 2004).

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2004b). Ethics as Social Practice: Introducing the Debate on Qualitative Research and Ethics [22 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal], 6(1), Art. 9. Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/1-05/05-1-9-e.htm (Accessed November 17, 2004).

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2004c). Unpolitical Political ethics, ethical unethical politics. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal], 5(3). Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-04/04-3-35-e.htm (Accessed November 17, 2004).

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2005a). Becoming like the other. In Wolff-Michael Roth & Kenneth Tobin (Eds.), Teaching together, learning together (pp.27-51). New York: Peter Lang.

Roth, Wolff-Michael (2005b). Communication as situated, embodied practice. In Tom Ziemke, Jordan Zlatev, Roz Frank & Réné Dirven (Eds.), Body, language and mind. Berlin: Walter De Gruyter.

Roth, Wolff-Michael, & Breuer, Franz (2003). Reflexivity and subjectivity: A possible road map for reading the special issues [17 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/ Forum Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal], 4(2). Available at: http://qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/2-03/2-03intro-2-e.htm (Accessed November 17, 2004).

Roth, Wolff-Michael; Lawless, Daniel & Tobin, Kenneth (2000). Time to teach: Towards a praxeology of teaching. Canadian Journal of Education, 25, 1-15.

Roth, Wolff-Michael & Middleton, David (2004). Knowing what you tell, telling what you know: Uncertainty and asymmetries of meaning in interpreting graphical data. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, April 12-16.

Roth, Wolff-Michael & Tobin, Kenneth (2002). At the elbow of another: Learning to teach by coteaching. New York: Peter Lang.

Roth, Wolff-Michael & Tobin, Kenneth (2004). Co-generative dialoguing and metaloguing: Reflexivity of processes and genres. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 5(3). Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-04/04-3-7-e.htm (Accessed November 17, 2004).

Schutz, Alfred & Luckmann, Thomas (1973). The structures of the life-world. (Translated by Richard M. Zaner & H. Tristram Engelhardt, Jr.). Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Smith, Dorothy E. (1990). The conceptual practices of power: A feminist sociology of knowledge. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Smith, Dorothy E. (1999). Writing the social: Critique, theory and investigations. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

ten Have, Paul (1999). Doing conversation analysis: A practical guide. London: Sage.

Varela, Francisco J. (1996). Neurophenomenology: A methodological remedy for the hard problem. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 3, 330-349.

Woolgar, Steve (1988). Reflexivity is the ethnographer of the text. In Steve Woolgar (Ed.), Knowledge and reflexivity: New frontiers in the sociology of knowledge (pp.14-36). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

SungWon HWANG wrote her doctoral thesis on learning science through laboratory activities at Seoul National University in Korea and currently is a postdoctoral fellow at University of Victoria. Her research themes range over phenomenological and dialectical perspectives on human practice, learning, and identity in science activities, recently in the context of multicultural and multilingual environments.

Contact:

SungWon Hwang

University of Victoria

PO Box 3010, STN CSC

Victoria, BC, V8W 3N4

Canada

Phone: 1-250-721-7834

E-mail: swhwang@uvic.ca

Wolff-Michael ROTH is Lansdowne Professor of applied cognitive science at the University of Victoria. His interdisciplinary research agenda includes studies in science and mathematics education, general education, applied cognitive science, sociology of science, and linguistics (pragmatics). His recent publications include Toward an Anthropology of Graphing (Kluwer, 2003), Rethinking Scientific Literacy (with Angela BARTON CALABRESE, Routledge, 2004), and Establishing Scientific Classroom Discourse Communities (co-edited with Randy YERRICK, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2005).

Contact:

Wolff-Michael Roth

MacLaurin Building A548

University of Victoria

Victoria, BC, V8W 3N4

Canada

Phone: 1-250-721-7885

E-mail: mroth@uvic.ca

Hwang, SungWon, & Roth, Wolff-Michael (2004). Ethics in Research on Learning: Dialectics of Praxis and Praxeology [39 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6(1), Art. 19, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0501198.

Revised 6/2008