Volume 4, No. 1, Art. 3 – January 2003

"Actually I Was the Star": Managing Attributions in Conversation

Sara-Jane Finlay & Guy Faulkner

Abstract: In this paper, we outline the parameters of a discursive approach to attributions in sport psychology. Attribution theory has had a strong presence within sport and exercise psychology. Attributions are the perceived causes or reasons that people give for an occurrence related to themselves or others. An attributional model, developed in educational psychology, has been most influential and often requires the researcher(s) or participants to determine the dimensional categorisation of attributions (e.g., internal-external, stable-unstable, controllable-uncontrollable). Assessing attributions in sport and exercise psychology has been almost exclusively through self-report questionnaires and entrenched within a limited theoretical perspective. In contrast, a discursive approach focuses on discourse and what is accomplished through people's talk. Such an approach would advocate a move from a view of talk (discourse) as a route to internal or dimensional categories to an emphasis on talk as the event of interest. Using principles of conversation analysis (CA), a critical examination of the traditional conceptualisation of attributions will be offered in this paper. Drawing on a corpus of data where athletes discuss their sporting performance, we consider the management of attributions as talk-in-action, rather than a series of discrete cognitive elements and dimensions. To illustrate the way that attributions are managed in conversation, we consider three areas—asking questions about loss, the interactional modesty inherent in discussing wins and the "slipperiness" of attributions in conversation. Finally, the implications of a discursive approach to the study of attributions in sport and exercise psychology are discussed.

Key words: attributions, conversation analysis, sport, discursive psychology

Table of Contents

1. The Study of Attributions in Sport and Exercise Psychology

1.1 Methodological and theoretical issues in the study of attributions

1.2 Conversation analysis

2. Corpus

2.1 Managing loss

2.2 Modest wins

2.3 Slippery attributions

3. Conclusion

1. The Study of Attributions in Sport and Exercise Psychology

Attributions are the perceived causes or reasons that people give for an occurrence related to themselves or others. From a social cognitive perspective, these attributions become an important determinant of individuals' emotions, expectations, and motivations towards similar events in the future. Attribution theory has had a strong presence within sport and exercise psychology (BIDDLE, 1993). In BIDDLE's (1994) analysis of all motivation papers published in two leading journals (International Journal of Sport Psychology and Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology) between 1979 and 1991, attribution papers were the most numerous. [1]

There have been a number of attributional theories and models that have been proposed (e.g., HEIDER, 1958; KELLEY & MICHELA, 1980). Attributional research in sport and exercise has been dominated by the use of WEINER'S (1985) model of achievement attributions (BIDDLE, 1993; HARDY, JONES & GOULD, 1996). Originally used in classroom settings, this theory has been expanded to include achievement in a variety of contexts such as sport and exercise. Key elements of WEINER's model will be summarised here although readers are referred to WEINER (1986) for greater elaboration. [2]

WEINER proposed that following an achievement outcome (i.e., success or failure), the individual experiences some immediate affective reactions regarding that outcome. The individual then engages in causal search in an attempt to determine why the outcome occurred before ascribing "attributions" as to the why. Originally, four main attributions ("attribution elements") were identified consisting of ability, effort, task difficulty and luck. Subsequent research has clearly demonstrated that there are many other causal ascriptions that might be used that are highly specific to the particular context. [3]

Once an attribution has been ascribed, it is processed in terms of its dimensional placement relative to dimensions such as stability, locus of causality and controllability ("attribution dimensions"). Firstly, the "stability" dimension refers to the extent to which the cause of an event is relatively stable. For instance, will a cause be unstable and rarely present again or will it be stable and always present? Secondly, there is "locus of causality" concerning whether the cause of an event was internal or external to the individual involved. The third dimension is "controllability" and concerns causes which are not at all controllable to causes which are potentially or completely controllable. This allows a distinction between elements that are internal but not controllable (e.g., innate ability) and internal factors that are (e.g., effort). [4]

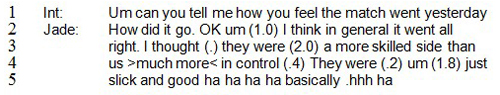

The attributions we give to explain events are then purported to have a range of psychological and behavioural consequences. It is the dimensions rather than elements per se that then influence future behaviour through the mediation of affective reactions and future expectancies (WEINER, 1985). Specifically, it is proposed that the locus of causality and control dimensions are the primary antecedents of affective reactions while the stability dimension is instrumental in the formulation of future expectancy. [5]

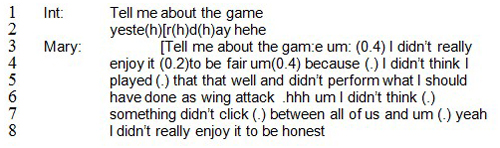

One of the important "laws" asserted by WEINER is that "outcomes ascribed to stable causes will be anticipated to be repeated in the future with a greater degree of certainty than outcomes ascribed to unstable causes" (1986, p.115). An individual who fails and attributes failure to stable causes will expect to fail in the future. An individual who succeeds and attributes success to stable causes will expect to succeed in the future. Such attributions might be linked to self-confidence via future expectancies and may also determine whether a person chooses to persist in a particular role or task. Such a line of thinking is clearly of interest to sport psychologists, for example, who may be attempting to enhance the self-efficacy of their elite clients or youth coaches who are concerned that a particular athlete always blames the referee for poor performances! Practical implications include the recommendation of encouraging athletes to "attribute success to internal, controllable and stable causes, and failure to internal, controllable but unstable causes" (HARDY, et al., 1996, p.109). [6]

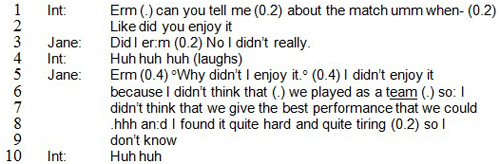

1.1 Methodological and theoretical issues in the study of attributions

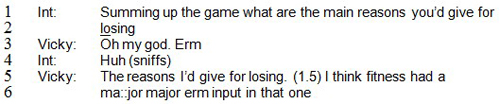

Assessing attributions in sport and exercise has been almost exclusively through self-report questionnaires and entrenched within a limited theoretical perspective (BIDDLE, 1993; BIDDLE & HANRAHAN, 1998), although the importance of examining natural talk in sequence has been recently recognised (BIDDLE, HANRAHAN, & SELLARS, 2001). In essence, qualitative studies of attributions in sport and exercise psychology have been rare and the field has been reluctant to consider more critical analyses of the attribution framework which have placed greater emphasis on the central role of language (e.g., ANTAKI, 1994; EDWARDS & POTTER, 1993). For ANTAKI (1994), there are three main critiques of traditional attribution theory in that it provides

"an account of explanation that was fixed on causation [which] is impervious to context; that it has a restricted and restricting conception of language, and language exchange; and that the rather rigid methods that are built on its theoretical base are not likely to pick up much variation in the ebb and flow of explanation in talk" (p.26). [7]

Underpinning these concerns is the assumption that the individual reporting their attributions is conceived as a scientific reporter solely interested in reporting the effective cause for a given phenomenon (ANTAKI, 1994; ANTAKI & LEUDAR, 1992; EDWARDS & POTTER, 1993), and not an interested participant in a social exchange. [8]

Subsequent work has focused on how everyday explanations should be treated as situated discursive phenomena (e.g., ANTAKI & LEUDAR, 1992; ANTAKI, 1996; EDWARDS & POTTER, 1993). We support calls for further qualitative exploration in attributional study in sport and exercise psychology (BIDDLE & HANRAHAN, 1998; BIDDLE et al., 2001). Specifically, a discursive approach could be informative (see McGANNON & MAUWS, 2000; FAULKNER & FINLAY, 2002). Although qualitative approaches may be interested in a content analysis of attributions made, most likely into the existing dimensions identified by WEINER (1986), a discursive approach opens a new field of investigation. [9]

The combined protocol of semi-structured interview and content analysis has been dominant within a cognitive approach to sport and exercise psychology (FAULKNER & FINLAY, 2002). Content analysis infers an examination of representational content rather than the outcome of speaking (WILKINSON, 2000) and therefore is distinct from discursive analysis. Thematic or content analyses fail to accommodate how and that experience is a linguistic phenomenon (McGANNON & MAUWS, 2000). Instead, outcomes are presented as a series of themes with supporting transcript data. Consequently, any "discourse" is seen as representing an underlying thematic structure or "psychic architecture". WILKINSON (2000) used content and discursive approaches to analyse the same data set (women talking about breast cancer causes). In considering the epistemological differences between the two she writes:

"From a content analytic perspective, the research participant has certain attitudes and beliefs about the causes of disease, and the research task is to elicit these. [...] From a discursive perspective, the research participant talking about the causes of disease (or anything else) is engaged in social interaction (with the interviewer, focus group moderator, and others present), and the research task is to understand how her talk is produced by and for its local interactional context. Content analysis, then, elicits "beliefs" about causes (i.e. cognitive content), and perhaps also information about the sources of these beliefs. [...] Discursive analysis examines the interactional work done by talk about causes (i.e. talk as action)" (WILKINSON, 2000, p.453). [10]

This interactional level, for ANTAKI (2000), and for the purposes of this paper, is where the action is. That is, a discursive analysis of attributions posits attributions as arising through a process of social interaction, rather than being the reflection of inner states and entities of the athletes' mind. This requires a shift in focus from a view of talk (discourse) as a route to internal or external events or entities (such as the dimensions of attributions) to an emphasis on talk as the event of interest (POTTER & WETHERELL, 1987; WOOD & KROGER, 2000). As EDWARDS and POTTER (1993, pp.37-38) write, "when people produce and respond to versions and explanations in talk, it is insufficient to take those versions either as neutral descriptions of the world, or as realizations of underlying cognitive representations". Such a stance must have serious repercussions for the interviewer, sport psychologist, or coach who asks an athlete "why" a particular outcome occurs1). It is not our intention to extensively critique traditional attributional theory, although this may be unavoidable, but to draw the attention of sport and exercise scientists to an alternative analysis personified by discursive psychology, and in this case, conversational analysis (CA). [11]

Arising from the field of ethnomethodology, and based on the work of Harvey SACKS (1992) CA can be viewed as the most micro-analytic variety of discourse analysis [see FAULKNER & FINLAY (2002) for a more detailed explanation of CA in the context of sport and exercise sciences]. It focuses on the elaborate and complex way in which speakers construct and understand conversation (POTTER, 1996; SCHEGLOFF, 1997; TEN HAVE, 1999). CA attends to the fine details of talk and emphasises its action orientation whereby all utterances "are treated as actions, that is, as meaningful, social doings" (WOOD & KROGER, 2000, p.12). From a conversation analytic perspective, talk is always produced in a context (or "occasioned"), in interaction with others. [12]

CA examines this finer detail of talk-in-action and as such talk is seen as a social activity rather than as expressing the speakers' internal thoughts (EDWARDS, 1997). Its analysis is based on the sequences in which conversations are usually constructed (a question generally elicits a response) and its production is appropriate for the occasion (generally people speak to manage situations). Talk is seen to accomplish interactional business (EDWARDS, 1997) so that all participants in the conversation are "active". When we look at attributions in conversation, we are more concerned with what is actually being accomplished by and through talk. Specifically, attributions are discursive actions. Asking an athlete "why" is first and foremost a form of social interaction and a construction of social reality. Traditionally, attribution research in the context of sport and exercise has not concerned itself with "interpersonal and functional factors that might constrain the attribution, such as who is doing the explaining, to whom the explanation is being given, or why an explanation is needed" (HILTON, 1990, p.65). A discursive approach, as embodied by conversational analysis could be used to address these questions. [13]

Using CA, we will now have a further look at some of the major tenets of traditional attribution research, and show how attributions are produced and managed in social situations, and demonstrate that the process of explaining causes and outcomes can be seen to "march to certain drumbeats and sequencing and conventional regulation" (ANTAKI, 1994, p.6). To illustrate the way that attributions are managed in conversation, we consider three areas—asking questions about loss, the interactional modesty inherent in discussing wins and the "slipperiness" of attributions in conversation. [14]

We shall look at a corpus of data that was collected by a final year undergraduate student for a research dissertation examining attributions in sport (WOODHALL, 2002). After four consecutive games, interviews were conducted with four female athletes of the same University netball team, providing a total of 16 interviews. The interviewer was a member of the netball club but did not play for the same team as the research participants. Approximately five hours of data were collected in the study. Participants gave informed consent to the project. [15]

In contrast to the initial analysis the taped interviews were transcribed orthographically. Unlike the "cleaned up"2) data upon which qualitative analysis is based, CA uses a more elaborate system to communicate some of the finer details of interaction. JEFFERSON (see ATKINSON & HERITAGE, 1984) is credited with creating the most widely used system (the Jeffersonian transcription system) and it involves the transcription of all the words and expressive features of the interaction including pauses, partial words, elongation and volume. Jeffersonian transcription is designed to represent the interaction or speech as spoken—not to turn it into a form of cleaned up written language. The data presented here draws on her transcription devices in a simplified form. Please note that symbols such as "?" or "." do not represent grammatical questions or clauses but voice cadence. A key is provided in the table below:

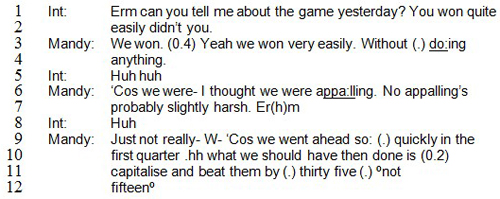

|

(.) |

Shortest hearable pause, usually less than 0.2 seconds. |

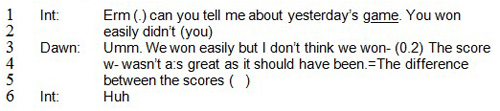

|

(0.2) |

Timed pauses |

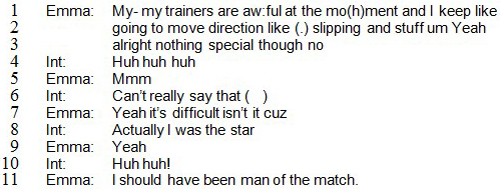

|

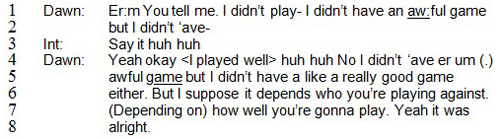

.hhh |

An in-breath |

|

wo(h)rd |

Laughter within the word |

|

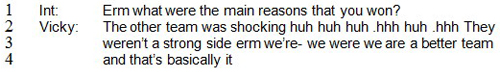

usu- |

The dash indicates a sharp cut-off of a word or sound |

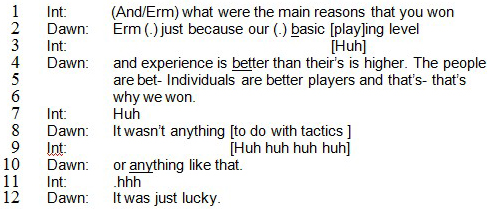

|

m::e |

The colons show the place that the speaker has stretched out the preceding sound |

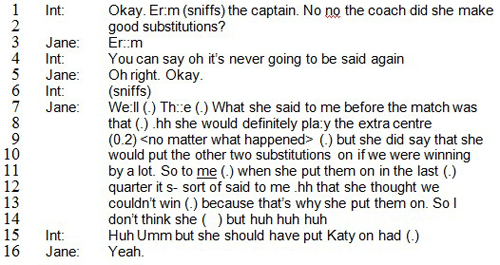

|

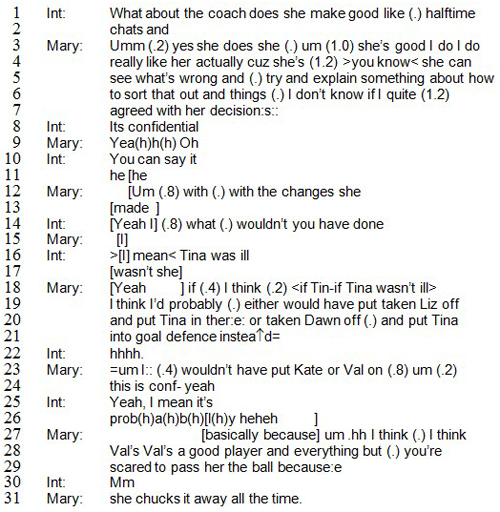

run= |

The equal signs indicates that the speech is linked and runs on |

|

feminist |

An up (or down) arrow indicates a rising or falling intonation |

|

you |

Underlined words or syllables show emphasis |

|

? |

A rising intonation at the end of a line |

|

°no° |

Speech enclosed by degree sounds is noticeably quieter than the surrounding talk. |

|

[no] |

The square brackets enclose the sounds that overlap with the next speaker |

|

>fast< |

Speech enclosed by these symbols is spoken either more quickly or slowly than the surrounding talk depending on their direction. |

Table 1: Jeffersonian Transcription Devices [16]

Attributions are often generated by extraordinary or unexpected outcomes (BIDDLE, 1993). In general, athletes are more likely to look for reasons for a loss than for a win. "It is likely that those who lose, especially unexpectedly, and/or those who are dissatisfied with their performance, will engage in more attributional thought than others" (BIDDLE, 1993, p.443). One of the simplest ways in which to illustrate how attributions are managed in conversation is through a consideration of the way that athletes are asked about and respond to questions on losing. [17]

Questions demand answers and coaches, physical education teachers and sport psychologists ask many. In conversation analysis, questions form part of an adjacency pair and such "pairs of statements [...] sets up expectations so powerful that they can actually determine meaning" (ANTAKI, 1994, p.69). ANTAKI (1994) writes that when a question is asked it prefers an answer "so anything you say will be taken to be either an answer, or a comment on the lack of an answer: there can be no escape from the expectation that you will orientate to what I say" (p.69). Questions often have "expected" answers but difficult questions may be marked out by the participants "as meeting or not meeting what is expected of them" (p.70). [18]

In traditional attribution research, concern is with how athletes attribute performance. From a discursive perspective, it could be assumed that discussions about losing cause interactional difficulty because athletes might be reluctant to discuss possible causes for their loss. In the extracts that we examine below this difficulty is highlighted by the way that the athletes struggle to answer the questions, the means they employ to buy time and put off answering. Four extracts from different participants are considered and their similarities offer evidence not only of the difficulty of discussing losses but how this interactional difficulty is managed in conversation.

Extract 1 [19]

Extract 2 [20]

Extract 3 [21]

Extract 4 [22]

All four of the extracts begin in a very similar manner—the interviewer asks the athlete to discuss games that they have lost and in each case, rather than providing a simple list, the respondents hedge their response and repeats the question asked by the interviewer. ANTAKI (1994) notes that when the second part of an adjacency pair is "not a "normal" response, then it will be done a bit less readily, and generally "marked" in some way—by a hedge, a request for clarification or both" (p.70). SACKS (1992) also suggests that open-ended questions such as these are often followed by a delay as respondents buy themselves some thinking time. In Extract 1 the interviewer asks Jade how she felt the match went yesterday. Jade's response is to repeat "how did it go" (line 2). In Extract 2 the interviewer asks Mary to tell her about the game yesterday and Mary begins her reply with "tell me about the game" (line 3). In Extracts 3 and 4 there is a small delay but shortly after being asked about their games, both Jane and Vicky repeat the question. In line 5 Jane rephrases the question initially asked by the interviewer "why didn't I enjoy it", while in line 5 Vicky also quietly repeats the interviewer's original question asking "the reasons I'd give for losing". [23]

Why do questions about losing follow this pattern? We would like to suggest two reasons. First, the repetition of the question buys some time for the respondent. It allows them to hedge their response and manage a discussion of losing with their interviewer. This provides evidence of the management of attributions in conversation. Second, repeating the exact (or very similar) words used by the interviewer affiliates the respondent with their questioner. We will explore these two issues further, illustrated using a more detailed analysis of the above extracts. [24]

BROWN and LEVINSON (1987; and see GOFFMAN 1955) suggest that co-conversants are concerned to protect face—both their own and others. Social interactions necessitate instances in which face is challenged or threatened. Asking about losing seems to be a "face-threatening act" and both the asking of the question and the response are managed through conversation. The interviewer does not find her questions easy to ask, she delays asking and then softens them through laughter. In both Extracts 1 and 3 the interviewer puts off the beginning of the question with an "um" or an "er". POMERANTZ (1984) suggests that delayers like this indicate interactional difficulty. In Extract 2 the interviewer laughs through the question (line 3). Interestingly Mary does not join in the laughter but overlaps the interviewers' question and repeats it. Her seriousness seems to be managing the discomfort of the interviewer in asking this question. By repeating it without the laughter she makes it easier for the question to have a serious response—treating the loss with a certain amount of gravity. JEFFERSON (1984) examined conversations in which people discuss their troubles. She found that those discussing their troubles often laughed after their utterance. The individual receiving the troubles does not laugh but "produces a recognizably serious response" (p.346). [25]

As mentioned above, the repetition of the question by the respondents buys them time in answering the initial question. Rather than immediately replying with a list of reasons for their loss, each athlete pauses before answering the question (these pauses range in length from 0.4 for Jane and Mary to 1.5 seconds from Vicky). JEFFERSON (1989) notes that the longest allowable gap in conversation is about one second, but that gaps of even 0.4 are hearable by the co-conversants and sometimes oriented to as indicating interactional difficulty. [26]

Interestingly the reasons given by each of the athletes are not generalisable, but are claimed as an expression of their own personal viewpoints—they are managing their accountability or responsibility for the loss. As we'll find in Extracts 5 to 8, athletes use collective terms to discuss their wins—it is "the team" that won, "we were a better team". In losing, the respondents hedge their reasons why using terms like "I think", "I thought", "I didn't think I played that well", "I didn't think that we played as a team". Unlike discussions of wins that are attributed to a group effort, the attributions given here are based on personal opinion and responsibility. Hedging statements like this suggests that there may be alternatives to the claims being made (MYERS 1989)—these are not the definitive reasons for losing the game but simply the personal opinion of one individual who was there and is accountable. The difference in footing of these remarks is of interest. GOFFMAN (1981) used the term footing to distinguish the different ways in which speakers take responsibility for their words. It manages communicative intentionality in a social manner (EDWARDS, 1997) and suggests varying goals that are interactionally managed. Speaking about wins in a collective term allows for the sharing of that win across the team—they can all accrue some glory. Using individualised footing that stresses that the perspectives presented are only those of the speakers' disengages them from the collective responsibility for analysing the loss. [27]

If, as the above analysis suggests, accounting for loss is an individualised action, it is interesting to note the rhetorical devices used by both the interviewer and respondents to affiliate with each other and ease the management of the conversation. In requesting information about the game, the interviewer sets up a request that can be either accepted or rejected by the interviewee. There is evidence that those making requests "see this import of their actions not merely as a possibility but as an actuality, and therefore they may examine whatever follows the [...] request [...] for how that object is displaying or implicating either acceptance or rejection" (DAVIDSON, 1984, p.102). In this context repeating the question provides evidence to the interviewer that their difficult question is being considered seriously. It may ease the asking of difficult questions. Let us look more carefully at Extracts 1 and 3. In the first laughter and agreement noises by the interviewer manage situations where loss of face is threatened, while the second shows the respondent using affiliation to set up their own explanation slot (ANTAKI, 1994; 1996). [28]

Talking about losing has implications for threatening face and is orientated to by both the interviewer and respondent as difficult and in need of management. In Extract 1 the interviewer begins by asking Jade how she felt the match went yesterday. Jade repeats the question and then hedges her answer (line 2). Her affiliation to the initial question is crucial here as the pause and hedge that follow it could suggest to the interviewer the potential rejection of the request (DAVIDSON, 1984). Both the repetition of the question and her extended pauses throughout can be read as hedges and delays to her ultimate response. When she attributes their loss to the "slickness" of the other team she laughs (line 5). The interviewer returns the affiliation provided by Jade earlier by laughing along with her (line 6). Their shared laughter works to manage the face threatening move that Jade's attribution of the win to the other team has opened up in the conversation. [29]

Similarly in Extract 3 the co-conversants orient to the difficulty of discussing losing and work to make the conversation successful. As noted above, the interviewer pauses and delays asking her question, and in the end, actually rephrases it. Rather than asking the more generalised factual question about the match (line 1 "can you tell me about the match"), she self-interrupts and turns to an emotionally based question (line 2 "like did you enjoy it") that allows the respondent to reply from a personalised basis rather than offering global or official judgements. Jane begins to repeat the question, pauses and responds that no she didn't enjoy it. This is a clear example of a "dispreferred" response. Dispreferreds usually follow a pattern that includes a pause and other delay devices such as partial repeats or hedges (POMERANTZ, 1984). These are usually followed by the negative response and a palliative to ease its delivery. So for instance, if you received an unwanted invitation to a friend's house for dinner, you might pause before responding "well, I'm afraid I can't, although I'd really like to". Jane begins to offer a classic dispreferred response. She makes a partial repeat of the question, hedges and pauses before giving her negative response (line 3). Importantly she does not offer a palliative to her negative assessment and this requires further work to manage the conversation. The interviewer's laugh (line 4) indicates the unexpectedness of this response and it is Jane's responsibility to repair the conversation. She does this by affiliating with the interviewer's initial question and creating an explanation slot for herself. [30]

ANTAKI (1996) notes that co-conversants can set up an explanation slot for themselves to mark what they say as problematic. In particular he refers to situations where the speaker must account for not delivering some utterance that had been set up. She makes obvious in her new question that her dispreferred response was hearably incomplete and needed explaining. Ensuring that the following statements are clearly seen as her perspective (line 6 "I didn't think that ...") she provides an explanation for their loss. The interviewer indicates her acceptance of this response by her final positive agreement through laughter ("huh huh"). [31]

A detailed consideration of the discussions between the interviewer and athletes about losing provides interesting evidence for the management of attributions in conversation. Repetition and hedging of responses (and questions) indicates that co-conversants are managing the orientation of the discussion. They are taking into account issues of face and self-presentation before providing responses. Clear evidence of affiliation throughout the discussions of losing also suggests that attributions are being managed. In most of the extracts affiliation worked as a delayer and a means to establish the terms of discussion. In the more detailed analysis provided, affiliation was used to get a conversation back on track. In the next section we turn from losing to winning and again consider how discussions of attributions are managed. [32]

Some researchers suggest that there are gender differences in attributions (BLUCKER & HERSHBERGER, 1983; DEAUX, 1984), but evidence for female athletes "doing modesty" is far from clear. The following extracts appear to offer some evidence for athletes talking down wins and being modest about their success. We offer two explanations for this apparent modest approach to winning, which from a CA perspective does not rely on gender. BIDDLE in fact notes that "the assumption [...] that males and females attribute success and failure in different ways in sport has not been supported with confidence" (BIDDLE, 1993, p.445; and see HENDY & BOYER, 1993). Instead, we suggest that displaying modesty is an aspect of managing conversations about winning. First, athletes are often encouraged by their coaches or sports psychologists to think critically about their wins rather than resort to unthinking celebration (HINKSON, 2001; ORLICK, 1990). Extracts 5 and 6 show the athletes talking down their win rather than celebrating their victory. Second, being modest about wins and your contribution to them may be an aspect of conversation in general. For example, the usual response to the question "how are you" is simply "fine". It would be unusual or unexpected for someone to reply "I'm absolutely fantastic, I look amazing in this outfit and everything is going my way". When things are going well we are more likely to respond in a more muted way such as "Great" or "I feel good today". Equally, we are unlikely to make obvious the modesty that is being displayed. We wouldn't say "I know the expected reply is fine, but today I feel fantastic and I want to rub your nose in it!" In the final two extracts we find evidence of two athletes making obvious the necessity of "doing modesty" in conversation about individual or team performance and success. [33]

In the following extract the interviewer asks Mandy about a game they won the day before. Mandy replies that they won easily and that she was disappointed in the way they played.

Extract 5 [34]

Although asked specifically about a win, Mandy does not respond by gleefully detailing the glories of her team and deriding the other team, instead she replies that they won the game, in fact it was an easy win, achieved with little effort on their part (lines 3 & 4). The interviewer's tacit agreement through laughter (line 5 "huh huh") to this statement provides the space necessary for Mandy to expand on her rather surprising remark. She responds with an extreme case formulation (POMERANTZ, 1986; see line 6 "I thought we were appalling"). Extreme statements such as this are rarely left by themselves in conversation—their extremeness requires recognition and softening. She orients to the exaggeration of this remark by saying that appalling is probably slightly harsh (line 6 & 7) and that her concern is that they did not beat the other team by more (line 11 & 12 fifteen points rather than thirty-five). [35]

A different kind of face is being protected here. Earlier we suggested that conversations about losing threaten face. Discussions about winning seem to be treated cautiously because of their ability to enhance face. The self-serving bias in attribution research suggests that individuals appear to attribute success to internal factors because they are motivated to enhance their self-esteem (MILLER, 1976). Mandy's attribution for their success is in fact external. She makes it clear that they played badly and still won so the other team must have been even more appalling than they were (line 3 & 4 her team won "without doing anything"). Rather than making an internal attribution to enhance self-esteem, Mandy seems to be deliberately devaluing their win and displaying modesty in its discussion, not trashing the other team. [36]

In the next extract, we find Dawn talking down the win and using a similar critique to that offered by Mandy.

Extract 6 [37]

The interviewer begins by asking about the game yesterday and suggesting that the team won easily. Rather than responding quickly and affirmatively, Dawn delays her response with an extended "umm" (line 3). Like Mandy, she agrees that they won easily but then begins to downgrade her initial assessment in line 3. Her slight pause to reformulate indicates her orientation to a statement that was hearably immodest and she begins to explain that the score was not as high as it could be and that they did not beat the other team by as much as they could have. [38]

In both instances, the athletes talk down their win. There appears to be some discomfort in boasting about scores and wins. Both Mandy and Dawn acknowledge that they won but rather than focusing on the positive aspects of the game, they instead focus on how badly the team played or how much better they could have done. A further confounding factor in understanding attributions about winning in conversation maybe provided by the context in which these conversations are formed. Coaches and sports psychologists often encourage athletes to critically reflect on their win, to bring to it the same kind of self-examination that may occur after a loss. Research on elite performers suggests that they are, or should be, personally concerned with taking responsibility for both their failures and their successes (HARDY et al., 1996; HEMERY 1991; NEWMAN 1992). BOND (1983) proposes that elite athletes in western cultures are more likely, in general, to ask "why" of both success and failure. Perhaps the conversations of Mandy and Dawn are reflecting a critical assessment of the game as encouraged by their coach and sporting culture. [39]

In the following extracts Emma and Dawn make clear the way that modesty is being "done" through conversation. In both instances, they bring into the open that modesty is used to manage the interaction between interviewer and athlete. Both women are aware that the conversations are being recorded and (as noted above) they have appeared hesitant to "blow their own trumpets". In the next two extracts we find out why and provide evidence for the role of modesty in discussions around winning.

Extract 7 [40]

Extract 8 [41]

In both of these extracts we find Emma and Dawn saying that they played well. This is unusual throughout the data where the women are often happy to discuss how well other members of their team have played (e.g. Natalie is a "bloody good shooter"; Val's a "good player"; Jade "was playing really well"; Amanda "had a stormer") but are hesitant to discuss their own success. That this is unusual in conversation is apparent in the manner in which the two co-conversants orient to the statements. Neither immodest declaration (from Emma that she was "man of the match" and that Dawn "played well") is allowed to pass without remark within the context of the conversation. [42]

Emma is complaining about her trainers and the interviewer seems to suggest that she can't use that as an excuse for not playing well. The option is to sound like one is boasting because (as the interviewer fills in) "actually I was the star" (line 8). Emma agrees and the shared joke between them is that she might have been so bold as to suggest that she was the "man of the match" (line 11). [43]

Dawn also makes obvious the inappropriateness of boasting in conversation. She begins by talking herself down—she didn't have an awful game but she is reluctant to say that it was good. Prompted by the interviewer, she says slowly "I played well" (line 4) and then laughs to soften the possible misinterpretation of this as a brag. She follows this up with a further explanation of why her game wasn't "a really good game either" (line 5). In the end, she simply claims that "it was alright" (line 7 & 8). [44]

JONES (1990) suggests that situations involving the self-presentation of goals, strategies or motives are constrained interpersonal acts that constitute our sense of social reality (SWANN, 1983). "That is, our endeavors to lead others to believe something about ourselves, whether freely chosen or dictated by the audience, limit the range of thoughts, feelings, and actions appropriate to that activity" (RHODEWALT, 1998). Similarly, ANTAKI (1994) sees explanations as a means of "constituting the social world [...] and constituting the people who navigate through it" (p.166). Dawn and Emma are managing the requirements for modesty in conversation while still acknowledging their success in the game. Harvey SACKS (1984) suggests that people spend a lot of conversation being ordinary—"in ordinary conversation, people, in reporting on some event, report what we might see to be, not what happened, but the ordinariness of what happened. The reports do not so much give attributes of the scene, activity, participants, but announce the event's ordinariness, its usualness" (p.414). Dawn and Emma are doing "being ordinary"—neither of them claim to be extraordinary players—in fact, they make it quite clear they're not. "It is not that somebody is ordinary; it is perhaps that that is what one's business is, and it takes work, as any other business does" (p.414). By making it clear how modesty usually constrains conversation the analyst is provided access to the inner assembly of conversation (ANTAKI, 1994). In the above extracts, the athletes are making obvious the necessity of doing "ordinary" or "modest" in everyday conversation. Being ordinary is the way that one constitutes oneself in social interaction—it is part of what constrains our interpersonal acts. [45]

In taking a discursive approach to attributions, we define attributions both "operationally and theoretically as things people do, not as things people perceive or think. They are defined as discursive actions, done in and through language, deploying but not accounted for by language's semantic structures" (EDWARDS & POTTER, 1993, p.24). Attributions are therefore seen as discursive actions that are "situated in activity sequences" (p.24). From this perspective, attributions do not provide an insight into the cognitive processes of the athlete, but are instead deployed in conversation where appropriate3). At the same time, attributions are linked to the audience—"reports attend to agency (causality) and accountability in reported events" (p.24). They are produced within the context of the conversation and therefore may vary across it or be different depending on who is asking the questions. In the following extracts we consider the "slippery" or shifting nature of attributions in conversation. Two areas are considered. First, we examine extracts where the athletes move between internal and external attributions in a matter of seconds. Second, we consider conversations where the athletes are blaming the coach for the result of the game. [46]

In this brief extract the interviewer and Vicky are discussing the reasons for winning.

Extract 9 [47]

The above extract provides further evidence of the interactional difficulty there is in discussing winning. The interviewer begins with a straightforward question (line 1 what are the main reasons for winning). Vicky responds by deriding the efforts of the other team—they were "shocking" (line 2). Her extreme case formulation requires recognition and softening which Vicky provides in the form of laughter (line 2 "huh huh huh"). She then softens this further by conceding that they were not a strong side and that the win occurred because her team was better. Her response to the initial question begins with an exaggerated statement. Its hyperbolic condition is oriented to and softened through laughter. Laugher is usually shared (JEFFERSON, 1979) and when the interviewer does not join in or pick up on the open transition point, Vicky softens her statement further by reducing the severity of her judgement. No longer are the team shocking, now they are simply not as strong, and finally she acknowledges that it was "basically" (line 4) that they were the better team. This final statement that Vicky suggests returns us to the bare bones of the question and is a long way from her initial statement that the other team was shocking. [48]

The answer then provided to the initial question by the interviewer is not that the other team was bad, but that Vicky's team was just a bit better. The downgrade of her opening statement about the other team could be a form of talking down the win, but it also makes her statement that "we were the better team" seem reasonable. When Vicky initially responds she suggests that the other team were shocking and that her team won the game because of their "shockingness". She begins by making an external attribution—they did not win because of their own skill but because the other team was worse. When the interviewer does not laugh with her, she softens her response and changes her attribution to internal factors (her team was "better" line 3).

Extract 10 [49]

Dawn offers several attributions for winning the game in this short extract. First, it is that their basic playing level (or skill) is better than their opponents (line 2). Second, they have more experience (line 4). Third, individually their players are more skilled (line 5). Fourth, their win was based on these criteria and had nothing to do with tactics or strategy (line 8). Finally she suggests that they just got lucky (line 12). In a very brief space of time Dawn has begun by making internal and controllable attributions that are largely stable in this instance. She concludes though by offering an attribution that is not only external, but also uncontrollable and unstable. [50]

How would this be accounted for in attribution research? The fundamental attribution researcher error (RUSSELL, 1982) occurs when the researcher assumes the presence of a particular property of an attribution (e.g. internal/external) that the participant themselves may not perceive. In this instance, the researcher may decide to only recognise the first or last attribution stated thereby ignoring the way in which this attribution is being sequentially and socially managed. ANTAKI (1994) critiques the "slipperiness" of attributional categorisation that has added further layers and dimensions onto the initial characterisations of internal/external. Attempting to fix the meanings of the categories does not recognise what these attributions mean socially or how they are accomplished in conversation. Conversation analysis would suggest that the range of attributions that she offered were part of the process of conversation, and earlier we have evidence of why she might conclude with luck. Dawn's claims to better skills and more experience come perilously close to sounding like boasting. It may be necessary within the context of the conversation to soften the apparent claims to expertise and credit some of them (tactics and strategy perhaps) to luck. [51]

The final two extended extracts suggest the contextual nature of conversations that require attributions.

Extract 11 [52]

Extract 12 [53]

In both of these extracts the interviewer has asked about the "competence" of the coach Bianca. The questions are quite general (Ex 12 line 1 & 2 "does she make good halftime chats" and Ex 11 line 1 & 2 "did she make good substitutions") and the interviewer is inviting the athletes to expand. Both begin to talk about their coach, but hesitate and ask for reassurance that the conversations are confidential and Bianca will not be privy to it. In Extract 11, line 3 Jane hedges ("erm") before replying and the interviewer, anticipating a dispreferred response hastens to assure her that "you can say" because "it's never going to be said again" (line 4). With this reassurance, Jane proceeds to explain that she felt the substitution the coach had made near the end sent the signal to the team that they were unable to win the game. She attributes a portion of their loss to a decision made by the coach. It is unlikely that she would make this same attribution in such a way if approached by Bianca. [54]

In Extract 12 Mary herself opens up the conversation to criticism of the coach by saying that she wasn't sure she "agreed with her decisions" (line 7). The interviewer reassures her that the conversation is confidential (line 8 "it's confidential" and line 10 "you can say it"). She offers several reasons for not agreeing with the coach before again requesting reassurance of the conversations confidentiality (line 24 "this is conf- yeah"). After the interviewer assures her that it will "probably" be confidential, Mary offers a strong critique of Val's playing style (line 31 "she chucks it away all the time"). Again, it is unlikely that we would find Mary offering the same attributions to either Bianca or Val if she had been questioned on the game, but she offers the perspective that both bear some responsibility for the loss. [55]

A consideration of the "slipperiness" of attributions highlights the management of attributions in conversation and two important facets of a conversation analytic approach. First, that we are concerned with the speakers' own practices and move from centralising the analysts' concerns to those of the participants'. In examining the quickly changing attributions given by Vicky and Dawn we do not find a straightforward list but instead examine how they are used in the conversation. Of central importance is the order of the attributions and the role that their sequential place has in the conversation. Second, the analysis highlights that the production of attributions is occasioned and produced within the context of specific conversations. POTTER and WETHERELL (1987) note that conversation varies over time and has many different functions that can be both global and specific: "a person's account will vary according to its function. That is, it will vary according to the purpose of the talk" (p.33). This assumes that conversations and discussions have an internal organisation and orderliness and that order "is produced by the parties in situ; that is, it is situated and occasioned" (PSATHAS, 1995, p.2). [56]

Accordingly, this suggests shifts in understanding attributions in conversation "from a concern with what people are talking about to a concern with what they are doing in and with their talk and from a concern with what happened to a concern with how events are discursively constructed" (WOOD & KROGER, 2000, p.17). Considering the management of attributions in conversation provides compelling evidence of how language is used to construct particular versions of the social world.

"First, it reminds us that accounts of events are built out of a variety of pre-existing linguistic resources, [...]. Second, construction implies active selection: some resources are included, some omitted. Finally, the notion of construction emphasises the potent, consequential nature of accounts. Much of social interaction is based around dealings with events and people which are experienced only in terms of specific linguistic versions. In a profound sense, accounts 'construct' reality" (POTTER & WETHERELL, 1987, p.33). [57]

In summary, we have attempted to use conversation analysis to demonstrate the social management of attributions, with reference to sporting contexts, in three ways. Specifically,

Questions about loss are troubling and create interactional difficulty that must be managed in conversation. Attributions can be managed through shared laughter, affiliation and accounting for unexpected replies.

Modesty in talking down wins and being ordinary may be part of this management and reflects the cultural context that frames the discussion.

Attributions can change over short periods of time and may be dependent on who is doing the explaining, to whom the explanation is being given, and/or why an explanation was needed in the first place. [58]

Overall, we argue that attributions are not produced in a straightforward manner, but are managed, framed and formed through conversations that are "occasioned". Conversation analysis, however, is not without its limitations. Feminist researchers have noted that the removal of context, other than that oriented to by the participants, may make conversation analysis fundamentally incompatible with politically engaged analysis. It may ignore structural and power differentials like gender or socio-economic status (e.g. BILLIG, 1999; SCHEGLOFF, 1997, 1998; WETHERELL, 1998). Additionally, conversational analysis requires a commitment to the centrality of social interaction. From this perspective, all potential research questions are always and necessarily framed by discursive interaction. [59]

This paper starts to redress the dearth of studies that have examined attributions in sport and exercise psychology using a different theoretical perspective and methodological approach commonly reported in the literature. This narrow theoretical and methodological conceptualisation might be associated with an apparent decline in popularity of attribution research since the mid-1980s (BIDDLE & HANRAHAN, 1998). In doing so, our analysis certainly confirms BIDDLE and HANRAHAN'S (1998) belief that attributional research using qualitative analyses will yield rich sources of data. However, two challenges are apparent in considering qualitative (and discursive in particular) methodologies. [60]

First, qualitative analyses will inevitably produce a more complex reading of attributions in sport and exercise. For example, a traditional thematic or content analysis is not easy due to the aforementioned conclusions! Content analysis suggests the simple counting up of the attributions given4); our closer examination of the way that attributions are produced in conversations suggests that it is not a simple process, rather it is one that is managed by the participants. The consideration of video data (HEATH, 1997), an exciting yet rare inclusion, examining how physical movements and the body feature with talk in accomplishing particular social actions and activities, might add further to this complexity. In contrast, we have argued elsewhere that conversation analysis can demonstrate how the interviewer contributes to the research process (FAULKNER & FINLAY, 2002). [61]

Second, a discursive approach does not sit comfortably with traditional approaches to attribution analysis. As ANTAKI (1994) advises us, in drawing on the work of EDWARDS and POTTER (1990; 1992), we need to:

"... drop our worries about what individuals are thinking and attend rather to what they are visibly doing—excusing, blaming, reporting and so on—and recognize that, in ordinary life, the 'truth' and 'falsity' of what they do is a matter of management and arbitration rather than a matter of accuracy against an experimenter-set norm. Participants in interactions are accountable to each other, and they know it; they tailor their words and deeds to the expectation that each is keeping various sorts of tabs on the other: legal, moral and general or contingent, localized and specific to this or that subculture, speech event or transient interest" (p.39). [62]

This is a considerable shift for sport and exercise psychology in that discursive psychology, and conversation analysis could be considered anti-cognitive (EDWARDS, 1997). From a research perspective, the traditional dimensions of attribution research simply do not work—instead they become a strategy for managing conversation. [63]

This does not necessarily invalidate traditional approaches to attributions in sport and exercise. Rather, EDWARDS and POTTER (1993) called for a relocation of attributional findings within a wider, discursive model. Attributions are treated as situated, discursive phenomena and traditional dimensions of controllability, stability, or locus of causality may be related more to types of rhetorical acts rather than perceptual abstractions (ANTAKI, 1994; EDWARDS & POTTER, 1993). From a practical perspective, the attributions you might attempt to "access" from an athlete as a sport psychologist, coach or researcher, are produced in a highly specific context, with a specific interactional purpose, and may not reflect any deeply held beliefs. This does not necessarily suggest we should stop, for example, promoting controllable attributions for success or failure to athletes. Rather, the critical question might become whether sport psychologists or coaches can be more aware of (and thus potentially more responsive to) common rhetorical strategies and the nuances of conversational interaction. This would be some undertaking. [64]

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers in addition to Stuart BIDDLE (Loughborough University) and Victoria CLARKE (University of Exeter) for their very helpful (and prompt) comments.

1) Much is made of the strength of assessing "spontaneous attributions" where causal thought is unprompted (e.g., BIDDLE & HANRAHAN, 1998). As these authors suggest, this is unlikely to occur in interviews when asking "why" questions prompts initial causal thinking. These authors do concede that spontaneous attributions may occur in this context. However, from a discursive perspective, assuming such spontaneous attributions do exist (outside of social interaction), then they are no more a route to the athletes' true inner state of mind. Similarly, distinctions between attributions made immediately after performance or some time after [e.g., VALLERAND's (1987) "intuitive-reflective appraisal model"] are not informative except within the context of each specific interaction. <back>

2) Interview data does not often take into account the pauses or the expressive nature of conversation. Often these are removed or "cleaned up" as part of the process of making the data "clean" or easier to understand. A conversation analytic perspective would suggest that this removes important aspects of the conversational interaction. <back>

3) It may be argued that conversation requires cognition. Discursive psychology, with its exclusive focus on the management of social interaction would not be concerned with the nature of these processes. McGANNON and MAUWS (2000) write, "in seeking an explanation for human behavior, discursive psychologists limit themselves to that which they know exists, i.e., conversations" (p.156). <back>

4) BIDDLE et al. (2001) have recommended the use of the Leeds Attributional Coding System (LACS; STRATTON, MUNTON, HANKS, HEARD, & DAVIDSON, 1988) in examining sporting/exercise attributions qualitatively. This system does attempt to address the relationship between language and cognition or thought. From a discursive approach, however, it is still ultimately a form of content analysis and ignores what language is actually "doing", while inferring the existence of inner cognitions held by the participant(s) (e.g., stability, controllability, or globality). <back>

Antaki, Charles (1994). Explaining and Arguing: The Social Organisation of Accounts. London: Sage.

Antaki, Charles (1996). Explanation slots as resources in interaction. British Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 415-432.

Antaki, Charles (2000). Simulation versus the thing itself: commentary on Markman and Tetlock. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 327-331.

Antaki, Charles & Leudar, Ivan (1992). Explaining in conversation: towards an argument model. European Journal of Social Psychology, 22, 181-194.

Atkinson, J. Maxwell & Heritage, John (1984) (Eds.) Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biddle, Stuart (1993). Attribution research and sport psychology. In Robert Singer, Milledge Murphey, & Keith Tennant (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Sport Psychology (pp.437-464). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Biddle, Stuart (1994). Motivation and participation in exercise and sport. In Sidonia Serpa, Jose Alves, Vitor Pataco & Vitor Ferreira (Eds.), International Perspectives on Sport and Exercise Psychology (pp.103-126). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology, Inc.

Biddle, Stuart & Hanrahan, Stephanie (1998). Attributions and attribution style. In Joan Duda (Ed.), Advances in Sport and Exercise Psychology Measurement (pp.3-20). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

Biddle, Stuart; Hanrahan, Stephanie & Sellars, Christopher (2001). Attributions: past, present and future. In Robert Singer, Heather Hausenblas, & Christopher Janelle (Eds.) Handbook of Sport Psychology (2nd Ed.) (pp.444-471). New York, NY: Wiley.

Billig, Mick (1999). Whose terms? Whose ordinariness? Rhetoric and ideology in conversation analysis. Discourse and Society, 10, 543-582.

Blucker, Judy & Hershberger, Eve (1983). Causal attribution theory and the female athlete: what conclusions can we draw. Journal of Sport Psychology, 5, 353-360.

Bond, Michael (1983). A proposal for cross-cultural studies of attribution. In Miles Hewstone (Ed.), Attributional Theory: Social and Functional Extensions (pp.144-157). Oxford: Blackwell.

Brown, Penelope & Levinson, Stephen (1987). Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davidson, Judy (1984). Subsequent versions of invitations, offers, requests, and proposals dealing with potential or actual rejection. In J. Maxwell Atkinson & John Heritage (Eds.), Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis (pp.102-128). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Deaux, Kay (1984). From individual differences to social categories: analysis of a decade's research on gender. American Psychologist, 39, 105-116.

Edwards, Derek (1997). Discourse and Cognition. London: Sage.

Edwards, Derek & Potter, Jonathon (1990). Nigel Lawson"s tent: discourse analysis, attribution theory and the social psychology of a fact. European Journal of Social Psychology, 20, 24-40.

Edwards, Derek & Potter, Jonathon (1992). Discursive Psychology. London: Sage.

Edwards, Derek & Potter, Jonathon (1993). Language and causation: a discursive action model of description and attribution. Psychological Review, 100, 23-41.

Faulkner, Guy & Finlay, Sara-Jane (2002). It's not what you say, it's the way that you say it! Conversation analysis: a discursive methodology. Quest, 54, 49-66.

Goffman, Erving (1955). On face work. Psychiatry, 18, 213-31.

Goffman, Erving (1981). Forms of Talk. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

Hardy, Lew, & Jones, Graham, & Gould, Daniel (1996). Understanding Psychological Preparation for Sport: Theory and Practice of Elite Performers. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Heath, Christian (1997). The analysis of activities in face to face interaction using video. In David Silverman (Ed.), Qualitative Research: Theory, Method and Practice (pp.183-200). London: Sage.

Heider, Fritz (1958). The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Hemery, David (1991). Sporting Excellence: What Makes a Champion (2nd Ed.). Wiley: New York.

Hendy, Helen & Boyer, Bonnie (1993). Gender differences in attributions for triathlon performance. Sex Roles, 29, 527-543.

Hilton, Dennis (1990). Conversational processes and causal explanation. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 65-81.

Hinkson, Jim (2001). The Art of Team Coaching. Toronto, ONT: Warwick Publishing Inc.

Jefferson, Gail (1979). A technique for inviting laughter and its subsequent acceptance or declination. In George Psathas (Ed.), Everyday Language: Studies in Ethnomethodology (pp.79-96). New York: Irvington Publishers.

Jefferson, Gail (1984). On the organization of laughter in talk about troubles. In J. Maxwell Atkinson & John Heritage (Eds.), Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis (pp.346-369). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jefferson, Gail (1989). Preliminary notes on a possible metric which provides for a "standard maximum" silence of approximately one second in conversation. In Derek Roger & Peter Bull (Eds.) Conversation: An Interdisciplinary Perspective (pp.166-196). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Jones, Edward (1990). Constrained behavior and self-concept change. In James Olson & Mark Zanna (Eds.), Self-inference Processes: The Ontario Symposium (Vol. 6, pp.69-86). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kelley, Harold & Michela, John (1980). Attribution theory and research. Annual Review of Psychology, 31, 457-501.

McGannon, Kerry & Mauws, Michael (2000). Discursive psychology: an alternative approach for studying adherence to exercise and physical activity. Quest, 52, 148-152.

Miller, Dale (1976). Ego involvement and attributions for success and failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 901-906.

Myers, Greg (1989). The pragmatics of politeness in scientific articles. Applied Linguistics, 10, 1-35.

Newman, Mark (1992). Perspectives on the psychological dimension of goalkeeping: case studies of two exceptional performers in soccer. Performance Enhancement, 1, 71-105.

Orlick, Terry (1990). In Pursuit of Excellence: How to Win in Sport and Life through Mental Training (2nd Ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Pomerantz, Anita (1984). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In J. Maxwell Atkinson & John Heritage (Eds.) Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis (pp.57-101). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pomerantz, Anita (1986). Extreme case formulations: a new way of legitimating claims. Human Studies, 9, 219-230.

Potter, Jonathon (1996). Representing Reality: Discourse, Rhetoric and Social Construction. London: Sage.

Potter, Jonathon & Wetherell, Margaret (1987). Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitudes and Behaviour. London: Sage.

Psathas, George (1995). Conversation Analysis: The Study of Talk-in-Interaction. London: Sage Publications.

Rhodewalt, Frederick (1998). Self-presentation and the phenomenal self: the "carryover effect" revisited. In John Darley & Joel Cooper (Eds.) Attribution and Social Interaction: The Legacy of Edward E. Jones (pp.373-398). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Russell, Dan (1982). The Causal Dimension Scale: a measure of how individuals perceive causes. Journal of Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 1137-1145.

Sacks, Harvey (1984). On doing "being ordinary". In J. Maxwell Atkinson & John Heritage (Eds.), Structures of Social Action: Studies in Conversation Analysis (pp.413-429). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sacks, Harvey (1992). Lectures on Conversation (edited by Gail Jefferson). Oxford: Blackwell.

Schegloff, Emanuel (1997). Whose text? Whose context? Discourse and Society, 8, 165-187.

Schegloff, Emanuel (1998). Reply to Wetherell. Discourse and Society, 9, 413-416.

Stratton, Peter; Munton, Anthony; Hanks, Helga; Heard, Dorothy & Davidson, Colin (1988). Leeds Attributional Coding System (LACS) Manual. Leeds, UK: Leeds Family Therapy Research Center.

Swann, William (1983). Self-verification: bringing social reality into harmony with the self. In Jerry Suls & Anthony Greenwald (Eds.), Psychological Perspectives on the Self (pp.33-66). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

ten Have, Paul (1999). Doing Conversation Analysis: A Practical Guide. London: Sage.

Vallerand, Robert (1987). Antecedents of self related affects in sport: preliminary evidence on the intuitive-reflective appraisal model. Journal of Sport Psychology, 9, 161-182.

Weiner, Bernard (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92, 548-573.

Weiner, Bernard (1986). An Attributional Theory of Motivation and Emotion. New York: Springer Verlag.

Wetherell, Margaret (1998). Positioning and interpretive repertoires: conversation analysis and post-structuralism in dialogue. Discourse and Society, 9, 387-412.

Wilkinson, Sue (2000). Women with breast cancer talking causes: comparing content, biographical and discursive analyses. Feminism & Psychology, 10, 431-460.

Wood, Linda & Kroger, Rolf (2000). Doing Discourse Analysis: Methods for Studying Action in Talk and Text. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Woodhall, Lucy (2002). How Effective is the Leeds Attributional Coding System as a Tool for Measuring Attributions in a Sport Setting? Unpublished undergraduate dissertation, Exeter University, UK.

Dr Sara-Jane FINLAY is a Senior Lecturer in Media with Cultural Studies and is Course Leader for the MA in Media at Southampton Institute. As of February 1st 2003, she will be Head of Media Studies at the College of St. Mark and St. John, Plymouth. As well as an interest in methodological issues, her research considers the construction of sexual personas and the negotiation of political identity in culture.

Contact:

Dr. Sara-Jane Finlay

Faculty of Media, Arts and Society

Southampton Institute

East Park Terrace

Southampton, SO14 0YN, UK

Tel: 023 8031 9658

E-mail: sara-jane.finlay@solent.ac.uk

Dr. Guy FAULKNER is a Lecturer in Exercise and Sport Psychology at Exeter University, UK. Guy's research interests lie primarily within the field of physical activity and psychological well-being. He is also interested in qualitative research. In particular, the use of ethnographic techniques, and conversation analysis are of interest.

Contact:

Dr. Guy Faulkner

School of Sport and Health Sciences

Exercise and Sport Psychology Unit, University of Exeter

Heavitree Rd., Exeter, EX1 2LU, UK

E-mail: G.E.J.Faulkner@exeter.ac.uk

Finlay, Sara-Jane & Faulkner, Guy (2003). "Actually I Was the Star": Managing Attributions in Conversation [64 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 4(1), Art. 3, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs030133.

Revised 6/2008