Volume 4, No. 1, Art. 17 – January 2003

Information Needs in Older Persons with Parkinson's Disease in Germany: A Qualitative Study

Michael Macht, Christian Gerlich, Heiner Ellgring & the Infopark Collaboration

Abstract: The study addressed the following questions: (1) What are the information needs of older people with Parkinson's disease (PD) and how can these needs be classified? (2) How effectively do persons with PD perceive professional information/communication giving? (3) Do information needs change over the stages of the disease? Data were collected in semi-structured conversational style interviews in three clinics as well as at home in two rural and urban areas in Germany. 33 persons with PD over 65 years of age with low, medium and high severity of disease participated voluntarily. The findings can be summarized as follows: (1) Information needs of older persons with PD refer to identifiable themes and contexts. Based on different motives a minority of participants expressed no information needs. (2) Various sources of information useful for persons with PD were identified (information from professionals, audiovisual material, written material, information given by members of the family, friends and other patients). (3) Information needs change over the phases of the disease. (4) Persons with PD described positive and negative experiences with information giving / communication by professionals and made various recommendations which may help to improve professional care. Four measures can be suggested to improve information giving and communication. First, any attempt to give information should be preceded by an assessment of the actual state of information needs of the person with PD. Second, for some persons with PD it may be indicated to postpone giving information to a later more appropriate time. Third, the most adequate information for a given person has to be selected from a variety of sources. Fourth, professionals should encourage active seeking of information and contacts between persons with PD. Fifth, information giving is most effective, (1) if patients and professionals meet at regular time intervals, (2) if professionals foster an atmosphere of confidentiality, openness and encouragement, (3) if information and interaction are adapted to the person with PD, and (4) if the information given is comprehensible.

Key words: information needs, old persons, Parkinson's disease, information giving, health care

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1 Participants

2.2 Interviews

2.3 Analysis

3. Findings

3.1 Classification of information needs

3.1.1 Categories

3.1.2 Information needs

3.1.3 Sources of information

3.1.4 No information needs

3.2 Information needs during the course of the disease

3.2.1 Typical experiences before, during and after diagnosis

3.3 Experiences with information giving and communication

3.3.1 Categories

3.3.2 Positive experiences

3.3.3 Negative experiences

3.3.4 Patients' view of how information should be given

4. Conclusions

The onset and development of a chronic and disabling illness such as Parkinson's disease (PD) can have a major impact on the quality of life of the ill person and his or her family (COHEN & LAZARUS, 1979; ELLGRING et al., 1993; MARTINEZ-MARTING 1998). PD permeates daily life and is characterized by heterogeneity of symptoms, variability of time course and complexity of treatment. The disease lasts between 10 and 20 years on average and confronts with ever changing problems. [1]

During the course of their illness, from first symptoms to severe disability, persons with PD repeatedly experience uncertainty and pose questions (PINDER, 1990). The management of these questions by health and social care professionals and the information obtained from them as well as from written materials and other sources is crucial for the well-being of persons with PD and their families. To meet the needs of older, chronically ill people, professionals must be prepared to work with and learn from patients and their carers and to incorporate such learning into professional practice (OERTEL & ELLGRING, 1995). The purpose of the present multinational project is to provide health and social care professionals with improved knowledge and understanding to enable them to enhance service delivery to older people within an atmosphere of client/professional partnership. A first step to achieve this goal is to describe information needs of older persons with PD and to collect their experiences with information giving and communication during the course of their disease. Thus, in the present study, older persons with PD were interviewed to address the following questions: (1) What are the information needs of older people with PD and how can they be classified? (2) How effectively do persons with PD perceive professional information giving and communication? (3) Do information needs change over the stages of the disease? [2]

Persons diagnosed with idiopathic PD were recruited from different sources (clinics and self-help groups) and socio-cultural backgrounds to ensure varying experiences. Interviews were conducted in three clinics located in different areas in Germany (Hesse, Southern and Northern Bavaria) and at home in two rural and two urban areas. [3]

Participants received written and verbal information about the purpose and nature of the project. It was emphasized that participation was entirely voluntary and no one was obliged to answer any questions asked. Participants were free to take a break or end interviews. Confidentiality and anonymity were assured and written consent was given by all participants. Interviews were audiotaped with participants' permission. [4]

In total, 33 persons (24 male, 9 female) were interviewed. Eight participants showed a low severity of disease level with unilateral or bilateral symptoms without impairment of balance (i.e. HOEHN & YAHR stages 1 and 2; the HOEHN & YAHR Scale [1967] characterizes the severity of the illness by classifying PD into stages 1 to 5, from mild to very severe1)). Nineteen participants showed a mild to moderate disease severity level (i.e. HOEHN & YAHR stage 3, with bilateral symptoms, some postural instability and balance problems, but with physical independence). Six participants showed severe disability, neither able to walk nor stand unassisted, or wheelchair-bound ( HOEHN & YAHR stages 4 and 5). Scores on the Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living Scale (1967) ranged from 90% to 10%, i.e. from a state of being independent with only some degree of slowness, difficulty and impairment to a state of being totally independent and invalid. Characteristics of interviewed persons with PD are summarized in Table 1.

|

Patient No. |

Severity of PD2) |

Age (years) |

Gender |

Years since diagnosis |

ADL (%)3) |

Depression4) |

|

13 |

low |

70 |

female |

6 |

90 |

no |

|

16 |

low |

68 |

male |

1 |

70 |

yes |

|

27 |

low |

74 |

male |

4 |

90 |

no |

|

28 |

low |

80 |

male |

10 |

90 |

no |

|

3 |

low |

65 |

male |

8 |

80 |

yes |

|

9 |

low |

67 |

male |

20 |

70 |

yes |

|

11 |

low |

67 |

male |

6 |

80 |

no |

|

12 |

low |

71 |

male |

10 |

80 |

yes |

|

31 |

medium |

71 |

female |

10 |

50 |

yes |

|

33 |

medium |

75 |

female |

6 |

70 |

yes |

|

4 |

medium |

84 |

female |

21 |

60 |

yes |

|

8 |

medium |

66 |

female |

15 |

80 |

yes |

|

14 |

medium |

75 |

female |

7 |

90 |

no |

|

18 |

medium |

73 |

female |

5 |

70 |

yes |

|

1 |

medium |

70 |

male |

4 |

30 |

yes |

|

2 |

medium |

73 |

male |

10 |

60 |

no |

|

5 |

medium |

70 |

male |

2 |

70 |

yes |

|

6 |

medium |

68 |

male |

14 |

70 |

yes |

|

7 |

medium |

68 |

male |

15 |

90 |

no |

|

10 |

medium |

68 |

male |

12 |

80 |

no |

|

15 |

medium |

75 |

male |

7 |

70 |

no |

|

21 |

medium |

71 |

male |

20 |

80 |

no |

|

22 |

medium |

78 |

male |

5 |

80 |

yes |

|

24 |

medium |

72 |

male |

8 |

75 |

no |

|

26 |

medium |

65 |

male |

7 |

50 |

yes |

|

29 |

medium |

71 |

male |

4 |

80 |

yes |

|

30 |

medium |

68 |

male |

6 |

60 |

no |

|

32 |

high |

67 |

female |

13 |

60 |

no |

|

19 |

high |

74 |

female |

5 |

40 |

yes |

|

17 |

high |

74 |

male |

2 |

40 |

yes |

|

20 |

high |

77 |

male |

13 |

30 |

yes |

|

23 |

high |

67 |

male |

12 |

30 |

no |

|

25 |

high |

74 |

male |

8 |

10 |

no |

Table 1: Characteristics of interviewed patients with PD [5]

Data were collected by two interviewers in a semi-structured conversational style interview (RUBIN & RUBIN, 1995). The interview was subdivided into several components. In the introduction, we ensured that the patient was fully informed about the purpose of the interview, that he/she had received and understood the information sheet and that he/she confirmed their full consent. Then permission was asked to record the interview. Briefly, the structure of the interview was explained: initially some questions on age, etc.—then a more general conversation focusing on information needs concerning their condition and how these needs have or have not been addressed. Finally, there were some brief questionnaires on the state of their present quality of life. The interviewer emphasized that the interview was primarily about the patients' information needs rather than the nature of their illness and its treatment. Before the interviewer began, he asked whether there were any questions on the part of the patient. Then, questions were posed regarding socio-demographic variables (age, gender, marital status, education, social and professional background, home circumstances) and facts pertaining to the illness (years since first symptoms and since diagnosis, medication, membership of PD association). The following essential part of the interview dealt with the actual questions and topics of interest. These topics were structured chronologically in four sections: (1) time before diagnosis, (2) time when diagnosis was confirmed, (3) time after diagnosis, and (4) discussion of patient's information needs and experiences in general. The interviewer orientated himself along the guidelines depicted in Table 2. Single interviews lasted 45 minutes on average. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed.

|

(1) Time before diagnosis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2) Time when diagnosis was confirmed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(3) Time after diagnosis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(4) Patient information needs in general |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 2: Interview guideline: Parts of the interview and topics to be discussed before finishing each part [6]

One third of the interviews were conducted in clinics specialized on the medical treatment of PD. The clinics made it possible to get access to severely disabled patients. Interviews were conducted in separated rooms undisturbed by noise and the usual activities in the hospital. The other two thirds of the interviews were conducted at home. The home environments as well as sociodemographic characteristics of participants varied considerably. We interviewed retired workers and academics, people living in the middle of the town or in the country, in their own houses or in rented flats, men and women living alone or with their families. Regardless of the location, it was made sure that a warm and personal atmosphere was created. On the one hand, patients were given as much time as they needed to articulate their ideas, feelings and experiences, on the other hand, they were given the opportunity to skip questions they did not want to answer and to have a break when they felt stressed or tired. The latter was of special importance for the six patients on the high disease severity level. During the course of the interview, many of the patients showed that they were emotionally involved with the themes. After the interview, they often pointed out that they felt relieved or that it was helpful for them to talk to someone who is interested in their problems and questions. [7]

The interviews were analyzed by three researchers in two stages. Data analysis involved the following steps (DEY, 1993): (1) Creating, assigning, splitting and splicing of categories, (2) Linking data, (3) Connecting categories, (4) Associating and linking categories, (5) Using maps and matrices (see figures below). First, based on field notes and after reading and rereading the interview transcripts, for an initial illumination of the data nine content-based categories were decided upon: (1) First signs: The patient speaks of the first signs of disease. (2) Diagnosis: The patient speaks of the circumstances under which the diagnosis was given. (3) Stress and burdens brought on by the disease: The patient tells of the physical and psychological problems which arose in the course of the disease or which are still current. (4) Need for information: The patient talks about what he wanted or still wants to know about the disease. (5) Knowledge about the disease: The patient recounts what he/she knows about the disease. (6) Helpful/useful information: The patients speak of disease-relevant information, which he considers positive. (7) Mediation of information (current state): The patient talks about how he received information (e.g. from whom, medium, circumstances). (8) Mediation of information (desired state): The patient tells how, in his opinion, information should be mediated (e.g. by whom, medium, circumstances). (9) Coping with the disease: The patient speaks about what helps or helped him/her, in order to live with the disease. The statements in the transcripts were assigned to one, and in rare cases to two, of these categories. These categories gave us an initial overview of the themes and experiences pointed out by the patients and were used for orientation and as background for the further analyses. In the second stage of the analysis, statements were selected from these prestructured data in order to develop more analytic frameworks with relevance to our key questions (classification of information needs, information needs during the course of the disease, experiences with information giving and communication). In this stage, the categories into which the data were placed were modified to accommodate new data until "saturation" was reached (DEY, 1993; SILVERMAN, 2000). The categories related to our key questions are described below. [8]

3.1 Classification of information needs

Our basic questions were: (1) What kind of information do persons with PD need and how can these information needs be classified? (2) What kind of information did they experience as helpful? (3) Are there any persons with PD who articulate no information needs and what are their motives? [9]

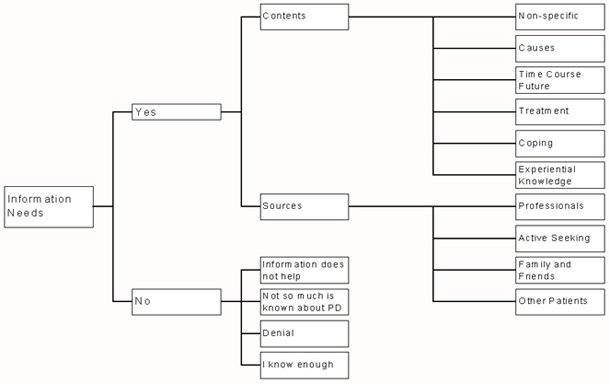

From interviewing, from reading and from re-reading the transcripts, the following scheme for classification of information needs emerged. First, statements were assigned to two broad categories: (1) Information needs and (2) no information needs. Second, statements implying information needs were classified with regard to their content (six sub-categories) and with regard to sources of information (four sub-categories). Statements expressing no information needs were examined with regard to underlying motives. Figure 1 shows in an overview how information needs were classified (for a further explanation see below).

Figure 1: Classification of information needs of older persons with PD [10]

The questions frequently posed by persons with PD and the information experienced as helpful were mostly related to one of six themes: Non-specific information needs, possible causes of PD, time course and future outlook, promises and pitfalls of treatment, coping with PD, experiential knowledge from contacts with other patients. [11]

Non-specific information needs

Persons with PD expressed that it is generally helpful to seek information on disease-related issues. For example, they said that knowledge, generally, helps to manage their situation and to prepare for the future. Examples of such statements are given below (translated from German by authors):

"You can never learn enough. Well, I also don't like to be surprised, never" (Pt 16, statement 31).

"One can deal with it [the disease], if one knows more. One should come to terms with it and not allow it to make you crazy" (Pt 16, statement 37).

"Don't bury your head in the sand. When I know something I can prepare myself for it so that when the next negative thing comes, it won't catch me by surprise" (Pt 18, statement 88). [12]

Possible causes of PD

Not surprisingly, persons with PD want to know the causes of their disease. One patient said:

"... it is important to me that I know where it [Parkinson's disease] comes from. What the causes are ..." (Pt 04, statement 58). [13]

And another one:

"Every disease has its causes and then I ask myself, where does Parkinson's come from, which is so hidden in the human body" (Pt 19, statement 25). [14]

Promises and pitfalls of treatment

Interviewed persons reported to be frequently confronted with questions and problems related to treatment. In PD numerous drugs given in different doses and different patterns over time. Doses and patterns have to be adapted to individual characteristics and to increasing severity of symptoms over the years. Medication may lead to side effects and interactions with other drugs. Drug treatment can be optimized by compliance and by frequent communication between the person with PD and his or her medical doctor. Thus, treatment issues evoke a bulk of questions for the person with PD. Examples are given below:

"I ask myself the question, in the course of time, how does the Parkinson medication get along with the medication of the other diseases" (Pt 01, statement 45).

"There are doctors who don't prescribe these expensive tablets anymore. But up to now I haven't had any problems with it" (Pt 01, statement 62). [15]

Additionally, a number of persons with PD asked questions on alternative treatment approaches and clinics for PD. [16]

Time course of the disease and future outlook

Naturally, a progressive disorder such as Parkinson's confronts the patients with questions about his future, both depressing and relieving:

"You have these thoughts that at some point you become a case for professional carers" (Pt 22, statement 45). [17]

For many it is essential to know that PD is not a "killer disease":

"And always to remember, you can't die from Parkinson's disease. For a start, this is a small consolation" (Pt 16, statement 74). [18]

Persons with PD need to know that the illness does not necessarily reduce quality of life if treated with appropriate medication. [19]

Coping with PD

Persons with PD repeatedly expressed the need to know more about how to actively improve their quality of life, e.g. by physical exercise, adequate nutrition or compliance:

"Because I'd like to know what I have and where I'm at, so that I can find possibilities to work at it, in a certain sense to work against it and to do something for my health" (Pt 27, statement 22).

"How one is supposed to behave, as someone with Parkinson's disease. That one keeps track of things, lives sensibly and isn't under too much pressure" (Pt 04, statement 55).

"If I know what I have, I can help in treating a disease. If I don't know what I have, where should I begin?" (Pt 16, statement 27). [20]

Experiential knowledge

A high proportion of participants mentioned that they got the most valuable information through contacts with other patients, either by observing them or by talking with them. We call this kind of information "experiential knowledge." It seems essential for the following reasons. Firstly, by comparison with other persons with PD they find it easier to judge their own situation:

"That was very good to see, ... to see that also others have to suffer" (Pt 09, statement 59).

"But then I thought, no, why should I get upset, if the course of disease is easier, really, what is there to agitate me?" (Pt 13, statement 20).

"Occasionally there were TV programs that I watched. I saw that Parkinson's disease shows itself in many different ways and that my disease belongs to the less severe ones" (Pt 21, statement 33).

"Well, naturally I've already seen [it] on TV and the boxer Ali, and the Pope—they also have it, the shaking and then I thought ... they have the money to cure themselves and so forth ..." (Pt 22, statement 07). [21]

Secondly, in conversations with other patients information is obtained that helps to cope with the disease. Such information is regarded as especially valuable, because it is not "theoretical," but derived from experiences:

"That's why these self-help groups are formed, to have the exchange of ideas. In this way one discovered how someone else overcame it and learnt by their example" (Pt 04, statement 30). [22]

Thirdly, meetings with other patients gives the opportunity both to give and to receive social support:

"The togetherness allows you to be freer" (Pt 04, statement 28).

"It is good, to talk with other patients" (Pt 11, statement 68). [23]

Older persons with PD mentioned several sources that were helpful for them in finding answers to their questions. Firstly, they received information from medical doctors and other professionals. Frequently mentioned were written materials (booklets and leaflets) from the neurologist, the general practitioner, the pharmacist and from the health insurance.

"Yes, I always get a brochure from my doctor, then I take a look at it and say to myself, 'I need this' ... Yes, he always gives me the latest information" (Pt 08, statement 105). [24]

Participants also mentioned that professionals gave valuable oral information, either in conversations with single patients or in discussions with groups of patients. Secondly, a number of persons with PD reported actively seeking audiovisual information and written materials from sources outside the health care system: books from the library or from the bookshop, articles from newspapers and magazines, videos from the self-help organization, information from television. Thirdly, they got useful written materials from members of the family or from friends:

"... my son, he studied, he is a businessman at IBM, and his wife, they provided me with all kinds of magazines, etc. They saw to it that I was properly informed" (Pt 22, statement 28). [25]

As a fourth source of information again the contact with other patients was identified. For example, one patient stated that the best information

"comes from people who themselves have the disease" (Pt 19, statement 48). [26]

A minority of older persons with PD expressed that they do not have any information needs. Four motives for having no information needs were identified: Firstly, it was stated that there is no reliable knowledge on PD. Secondly, that it does not change anything to know more of the disease:

"I took the medication that he prescribed. And otherwise I left it at that" (Pt 12, statement 26).

"It doesn't help, I don't get anything from knowing more" (Pt 15, statement 73). [27]

Thirdly, participants stated knowing enough. Finally, some said that they repressed dealing with the disease and related problems, and therefore felt no need for information:

"There are some people who want to know everything. I am someone who represses it a little" (Pt 19, statement 58). [28]

Although most persons with PD need information, some patients should be approached more carefully with information. Effective information giving means taking into account the individual patient's unique circumstances. [29]

3.2 Information needs during the course of the disease

Interviews showed that different information needs arise in persons with PD before diagnosis, in the period of time when diagnosis is given, and in the years after diagnosis. Before diagnosis persons with PD experience changes of movement or well-being which they often attribute to influences other than PD. In this situation it seems essential to know where and from whom high quality medical examination and advice can be procured. At the time of diagnosis basic questions on the nature of the disease arise: its possible causes, its symptoms and approaches to treatment. After diagnosis persons with PD often want to reduce uncertainty with regard to future developments and seek information on the various ways of coping with PD. However, this characterization is only a general one. The change of information needs over time varies individually depending on experiences within the health and social care system. We attempted to filter out typical experiences and developments during the course of the disease. [30]

3.2.1 Typical experiences before, during and after diagnosis

According to the interviews the individual developments of PD can be subdivided into problematic and unproblematic courses. [31]

In the case of a unproblematic course, the patient visits a general practitioner after the first symptoms become evident. The general practitioner sends the patient to a neurologist who diagnoses the disease. Diagnosis and disease-related information is given immediately to the patient and often also to the members of his or her family. After the diagnosis the patient often joins a self-help group. Persons with PD reporting such an unproblematic course typically get information according to their needs and feel in a position to cope with their disease. Unproblematic courses were reported by participants 2, 5, 9, 11, 16, 18 and 19. [32]

In the case of a problematic course of PD, we distinguish between two main developments: First, problems arise with first symptoms and diagnosis. For example, the diagnosis made by the general practitioner or a specialist is incorrect and is not corrected immediately. Patients are told that they are "too young for PD," or that they were "imagining the disease" (experiences such as these were reported by participants 3, 4, 7, 8 and 17). It may also be the case that the symptoms are not familiar to the general practitioner. Under these circumstances months or even years may elapse until a correct diagnosis is made. During this time the person with PD poses numerous questions which are not answered satisfactorily. It may even be the case that patients are not informed at all or only after a long delay. Indeed, one participant (12) reported that diagnosis was made and drug were given without any information on PD. Only after months he realized having a severe neurological disease. [33]

Second, problems may arise after the formal diagnosis. A number of participants reported disappointing or negative experiences with professionals during the period of time after diagnosis. They often felt "left alone" and criticized "too long waiting periods" or thought that "drugs were tested on them" (e.g. participant 20). Additionally, problems with the health insurance company arose. For example, physiotherapy was no longer paid. [34]

3.3 Experiences with information giving and communication

Participants described positive and negative experiences with professional information giving and communication, and they gave their opinion on how information giving and communication should be improved. [35]

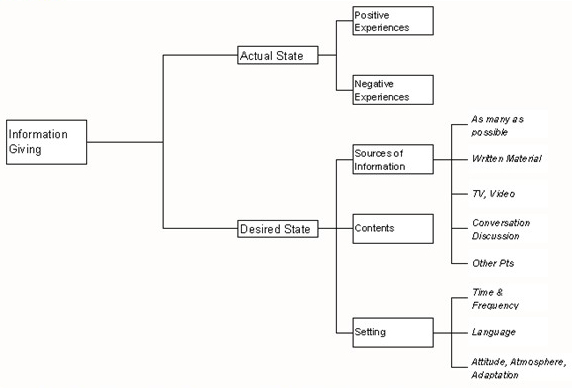

The statements were assigned to two broad categories: actual and desired status of information giving and communication. Statements referring to actual status were subdivided further: positive and negative experiences. Statements referring to a desired status of information giving were subdivided into subcategories: contents of information that should be given, sources of information that should be used, and setting of information which would be most helpful. Figure 2 shows in an overview how statements on information giving were classified.

Figure 2: Experiences of older persons with PD with information giving and communication [36]

Participants who described positive experiences with information giving and communication emphasized the role of regular meetings with medical doctors. For example, they reported meeting the neurologist at a regular time interval of four weeks and talking with him for up to 20 minutes at each meeting. Under such and similar circumstances older persons with PD felt well-informed. They pointed out that they got helpful information on the nature of the disease or on medication. The benefit of regular meetings with doctors seems to be enhanced when written material is given in addition to oral information. Information from leaflets, brochures and books helps them discuss their problems with professionals. The following statements are examples of such experiences:

"If some difficulties arise today, my wife and I talk with our general practitioner. He normally suggests dropping one medication or taking only half of another, and then we try it" (Pt 01, statement 63).

"Yes, he (the neurologist) always gives me the latest information" (Pt 08, statement 106).

"Yes. He (the neurologist) always says that we can devote at least 20 minutes to it" (Pt 14, statement 17).

"He spoke with me about how I feel and it is especially important to me—as probably for many others, too. I see him regularly every month" (Pt 27, statement 18).

"Yes, I always get a brochure from my doctor, then I look at it and say 'I need this'" (Pt 08, statement 105). [37]

Participants also indicated that it was beneficial to them to use written materials, TV programs, videos etc.:

"Well there are some [books] which are easy to understand. You can read it well, think yourself into the matter and how it works and what it is and such ... Well written, such that anyone can read it relatively well." (Pt 10, statement 41). [38]

If persons with PD are asked how they satisfy their information needs, again and again they mention contacts with other patients.

"You could talk with anyone, everyone here had the disease, just in a different way. And this ... it helped me so much" (Pt 09, statement 42). [39]

Therefore, it can be an additional function of health and social care professionals to promote active information seeking in persons with PD and to foster contacts between patients. [40]

When older persons with PD described negative experiences with information giving they mostly stated that they did not get enough information. The following statements exemplify these experiences:

"He [the neurologist] said only a little, then he sent me back to my general practitioner" (Pt 23, statement 33).

"So there wasn't too much information to be had from the medical side?—Actually not, you can't really say" (Pt 23, statement 34).

"It's not like he didn't explain anything, but it just wasn't enough, no, we wanted a little more" (Pt 23, statement 35).

"I would say, the bad doctors just leave you standing there. They aren't prepared at all" (Pt 27, statement 70). [41]

This lack of information is, in the view of persons with PD, caused by two factors. Firstly, it was stated that doctors usually do not have enough time to answer adequately the questions of their patients. One patient criticized that the diagnosis was told within 5 to 10 minutes without any further explanation. Exemplary statements related to the problem of time are given below:

"If they (the doctors) don't have the time, then it goes so fast that, if you're not informed, you can hardly retain what has been said" (Pt 04, statement 63).

"Also in the Parkinson clinic it's the same as in other fields, the doctors always have so little time" (Pt 13, statement 80).

"He always said, take this, there's a good reason for it. Without informing me more or talking to me longer. I did trust him, but all doctors just have too little time" (Pt 18, statement 30).

"If the doctors had more time, the information would be more important, but oftentimes there isn't any time. There are simply too many patients" (Pt 04, statement 34). [42]

Secondly, persons with PD stated that some doctors do not seem prepared for communication with patients. These doctors may lack communication skills and, for example, use too many medical terms which are hard to understand by the patient. Some patients even had the impression that doctors do not know enough about PD:

"The doctors need to be more informed" (Pt 10, statement 50).

"I gain nothing from it, if someone explains to me in medical terms and I understand only 10%. And as for asking questions, the doctor's already standing up and fetching the next patient into the room. Just the way it is, I've experienced it" (Pt 16, statement 67).

"The time factor and the medical terminology, these have to be there. Otherwise it is mediated very modestly by the doctors" (Pt 16, statement 68). [43]

3.3.4 Patients' view of how information should be given

Interviewed persons with PD gave various opinions as to what information they regard as crucial, from where and from whom this information should be sought, and in which setting information should be given. [44]

Contents

The information persons with PD expect to be given corresponded to their information needs as they were described above, e.g. the causes of the disease, its time course and future development, treatment issues and ways of coping. An example:

"What, how far is the research and will there in future be medication, better medication that will help me? That is one thing that interests me. Another thing that really interests me, how can I eat healthily? And what are the proper physical exercises?" (Pt 16, statement 57). [45]

Sources

Persons with PD gave various opinions on the best source of information and where it can be obtained. Some stressed the role of verbal information from the neurologist, others the importance of comprehensible written and audiovisual material. A third group of patients suggested using as many sources of information as possible. Also, the role of active information seeking was emphasized as well as the support in information seeking given by members of the family, friends and other patients. [46]

Setting

Interviewed persons with PD gave numerous statements on how information should best be given. First of all, they emphasized the necessity of frequent and regular contacts between patients and professionals. For the ever changing problems in a chronic and progressive disorder such as PD this is in fact a prerequisite for care and service. Secondly, it was emphasized repeatedly that information should be comprehensible, "short and to the point," and as free as possible of medical terminology:

"And with the fundamental literature, I find it shouldn't be written in such length. Instead it should be short and to the point" (Pt 19, statement 67).

"But for the man on the street, who isn't familiar with it, one should [talk] in more detail with him" (Pt 18, statement 85). [47]

Thirdly, persons with PD gave their opinion on how information should best be given. They stated that an open, honest and encouraging attitude of the professional is essential. Information giving seems to be most effective in an atmosphere of confidentiality and honesty.

"Yes, in particular the truth must be told. That there is still no real aid with respect to medication and healing methods. It doesn't help to give the patients hope, when there is none. I personally, I can take the truth, which some others might then again not be able to do" (Pt 22, statement 60).

"Tell the truth. That's what they did with me. In this way I could prepare myself mentally for it" (Pt 26, statement 49).

"Yes, that for a start one is honest with the patients" (Pt 27, statement 61).

"In my opinion, he should have spoken encouragingly. Not patronizingly, but from the bottom up. Give courage. That's the most important thing in this whole situation" (Pt 27, statement 62). [48]

Finally, it was stressed that the type of information and the ways in which the information is given have to be adapted to the individual: to his or her readiness to receive information, to the problems and questions asked, to level of education etc.

"Question-Answer. That would be ideal" (Pt 18, statement 86). [49]

The findings of qualitative analyses of interviews with older persons suffering from PD can be summarized as follows:

Information needs of older persons with PD refer to identifiable themes, topics and contexts (e.g. possible causes of PD, issues of treatment, future outlook, coping, knowledge from other PD patients). However, based on different motives such as coping through denial some persons with PD expressed no information needs.

Various sources of information useful for persons with PD were identified: (a) verbal information given by medical doctors or other professionals, (b) information from audiovisual material, (c) written material, (d) information given by members of the family or friends, (e) social contacts with other patients. Persons with PD emphasized consistently that social contacts with other patients are an especially important source of information. These contacts enable patients to compare their problems with problems of the others, to see how others cope with the disease and to exchange ideas and information crucial for their well-being. It was also stressed that active seeking of information is necessary to satisfy information needs.

Interviews indicated a change of information needs over the phases of the disease. Before diagnosis, persons with PD experience changes of bodily and psychological functions which are often attributed to other causes than PD. At the time of diagnosis, precise information on the nature of PD is urgently needed. In later years, information on how to cope with symptom changes, drug side effect and severe impairment become essential.

Persons with PD described positive and negative experiences with information giving / communication by professionals. Based on these experiences they made various recommendations which may help to improve health care. [50]

First, any attempt to give information should be preceded by an assessment of the actual state of information needs of the person with PD. Information needs may differ depending on disease severity, specific symptoms, specifics of treatment, previous experiences and actual knowledge. Second, for some persons with PD it may be indicated to postpone giving detailed information to a later more appropriate time. Due to anxiety, depressive moods and other circumstances some persons do not experience any information needs and this state of mind should be handled with care. Third, the information has to be selected from a variety of sources. In many cases it is probably appropriate to use as many sources as possible (e.g. written materials, videos). Fourth, professionals should encourage active seeking of information as well as contacts between persons with PD. Comparison with others enables patients to put their own situation into perspective. In conversations experiential knowledge is acquired which helps to cope with disease-related problems. Furthermore, a sense of togetherness and shared identity in PD self-help groups are often experienced as a great relief. Finally, information giving is most effective if it meets the following criteria: (1) Patients and professionals meet at regular time intervals. (2) Professionals foster an atmosphere of confidentiality, openness and encouragement. (3) Information and interaction are adapted to the information needs and individual characteristics of the person with PD. (4) The information given is clear and comprehensible. [51]

This study was supported by the European Community (Quality of Life and Management of Living Resources, Key Action: The ageing population and their disabilities). It is part of the Project INFOPARK (Information, health and social needs of older disabled people (Parkinson's Disease) and their carertakers, Proposal Number: QLRT-2000-00303) with participants from the United Kingdom (A. BAYER, W. TADD, R. TOPE, L. GRAHAM, M. HARRIS), Finland (P. ROUTASALO, P.T. LEINO), Spain (L. CARRASCO, M.J. CATALAN), Estonia (P. TABA, U. KRIKMAN), Portugal (P.W. KING, D.A. PINTO, A. LOPES), Greece (S. KASTANA, A. THEODOROPOULOS, ) and Germany (H. ELLGRING, M. MACHT, C. GERLICH).

1) The Schwab and England scale is used frequently in assessment of PD; it reflects the patient's ability to perform routine activities of daily living in terms of speed and independence: a score of 100% implies total independence, whereas diminishing percentages correlate with both slowness in completing routine tasks and progressive loss of independence. <back>

2) "Low" represents HOEHN and YAHR's stages 1 and 2. "Medium" represents stage 3. "High" represents stages 4 and 5. <back>

3) ADL: Activities of Daily Living were rated on a scale from 0% to 100%, whereby 0% represented total disability and 100% represented total independence. <back>

4) At the end of the interview, participants were asked whether, during the past month, they had "often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?" They could answer "yes" or "no". <back>

Cohen, Frances & Lazarus, Richard S. (1979). Coping with the stresses of illness. In George C. Stone, Frances Cohen & Nancy E. Adler (Eds.), Health Psychology—A Handbook (pp.217-254). San Francisco: Jassey-Bass Publishers.

Dey, Ian (1993). Qualitative data analysis. London: Routledge.

Ellgring, Heiner; Seiler, Sigrid; Perleth, Brigitte; Frings, Willi; Gasser, Theodor & Oertel, Wolfgang (1993). Psychosocial aspects of Parkinson´s Disease. Neurology, 43 (Suppl. 6), 41-44.

Hoehn, M. Margaret & Yahr, Melvin D. (1967). Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology, 17, 427-442.

Martinez-Martin, Pablo (1998). An introduction to the concept of "quality of life in Parkinson`s disease". Journal of Neurology, 245(1), 2-6.

Pinder, Ruth (1990). What to expect: information and the management of uncertainty in Parkinson´s Disease. Disability, Handicap and Society, 5, 77-92.

Rubin, Herbert J. & Rubin, Irene S. (1995). Qualitative Interviewing. Thousands Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schwab, Robert S. & England, Albert C. (1969). Projection technique for evaluating surgery in Parkinson's Disease. In Francis J. Gillingham & Margaret C. Donaldson (Eds.) Third Symposium on Parkinson's Disease (pp. 152-157). Edinburgh: Livingstone.

Silverman, David (2000). Doing qualitative research. London: Sage Publications.

Michael MACHT has undertaken research into the psychological aspects of Parkinson's Disease and has also been involved in the development of psychological interventions for PD patients and their carers as well as for patients suffering from other chronic diseases.

Christian GERLICH has undertaken cross-cultural research on PD in Spain and Germany as well as on gender differences in the use of health services.

Heiner ELLGRING is member of the Psychological Advisory Board of the German PD Association (dPV), and co-editor of the EPDA magazine (European PD Association). He has considerable experience with research on psychological and social aspects of PD and other psychological and neurological disorders.

The INFOPARK collaboration is an interdisciplinary group of researchers from seven European countries (United Kingdom, Finland, Spain, Estonia, Greece, Spain and Germany). The group is carrying out a project on information needs in older persons with PD and their carers supported by the EU.

Contact:

Michael Macht

Institute for Psychology (I)

University of Wuerzburg

Marcusstrasse 9-11

97070 Würzburg, Germany

E-mail: macht@psychologie.uni-wuerzburg.de

Macht, Michael; Gerlich, Christian; Ellgring, Heiner & the Infopark Collaboration (2003). Information Needs in Older Persons with Parkinson's Disease in Germany: A Qualitative Study [51 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 4(1), Art. 17, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0301176.