Volume 3, No. 1, Art. 20 – January 2002

Using Qualitative Methods in Franchise Research—An Application in Understanding the Franchised Entrepreneurs' Motivations

Claire Gauzente

Abstract: Until now the research on franchising has been lacking in France. However, France was one of the first European countries to develop numerous franchise units. The focus of this text is on the selection process of franchise as narrated by 21 franchised entrepreneurs.

Previous franchising research indicates that qualitative studies are not sufficiently used in this field. Therefore, it was decided to interview franchisees in order to better understand how and why people choose franchise rather than other forms of business. Two different methods were used for analysis: thematic content analysis and statistical textual analysis.

In comparison to the findings from past research, the results provide insights on the reasons for choosing franchise.

Key words: franchise research, franchised entrepreneur, motivation, statistical textual analysis, content analysis

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Objectives

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1 Results of the thematic content analysis

4.2 Results of the statistical textual analysis

5. Significance of Findings

6. Conclusion

Appendix 2: Brief description of interviewees

Franchise is a system whereby independent entrepreneurs work together in a contractual network. The franchiser creates a franchise concept (based on original service or product). In order to develop it commercially, he or she contracts with other entrepreneurs, the franchisees, who commercialize the franchiser's service or product. Hence even if the parties are juridically independent they work hand in hand which is formalized through the franchise contract. [1]

To date research on franchising is underdeveloped in France. However in Europe, France entails the largest number of franchise units and yet this area of research remains largely unexplored. At the Conference of the International Society of Franchising in 2000 (ISOF), a very low percentage of papers dealing with French franchise were presented. Over the last 13 years, such papers indeed represent hardly 4% of the papers with an international coverage (YOUNG, McINTYRE, & GREEN 2000). [2]

From an economical standpoint, franchising is an attractive business system. One of the reasons for this is that the entrepreneurs realize that their entrepreneurial project faces many risks if they try to develop their business on their own. For them, franchise represents the opportunity to set up a business while benefiting from the "security" of an organized system: the franchise network. [3]

The research presented in this paper is part of a larger program where franchise selection as well as franchisees' satisfaction are investigated. In franchising research, understanding the reasons why people choose to join a franchise is one of the central research topics (HING 1993, 1995, WITHANE 1991). For this purpose, franchise researchers mainly use coarse-grained research with a clear preference for mail surveys. The questionnaires are based upon inventories of potential reasons for joining franchise. The elaboration of those inventories remains unclear: some of them stem from theoretical examination of the advantage of franchise (mainly from Transaction Cost Theory), others are drawn from journalistic publications and some others from short interviews. Research on selecting franchise was available in the 80s and the beginning of the 90s. However it makes little sense to use (mainly) American dated inventories of potential reasons for investigating the French field. [4]

The need for more qualitative approaches in franchising research is reflected in the statistics provided by YOUNG et al. (2000). Over the last 13 years (1986-1999) the percentage of qualitative research in franchising has been 7.7%. This was also underscored in the extensive review by B. ELANGO and V. FRIED (1997). These researchers observed that almost all research has been coarse-grained and the presence of qualitative research almost non-existent. Hence the knowledge about franchise is almost never fleshed out with franchisees' (or franchisers') genuine experiences. This lack of qualitative franchising research appears to us as a handicap particularly when considering entrepreneurs' motivations to become a franchisee. [5]

This article aims at delineating a specific understanding of the French franchised entrepreneurs. In the first part, we will present the extant literature dealing with franchisees' motivations, in the second part, we will expose the qualitative methodology that was used and lastly the results are listed and discussed. [6]

2. Theoretical Background and Research Objectives

The long-term survival of a franchise system depends on the willingness of the franchisees to pursue the relationship with the franchiser (MORRISON 1997). The relationship management can be conceived as an evolutionary phenomenon in which the initial tie is the decision to purchase a franchise. Hence the decision process is the initial, crucial step that will condition the relationship between the franchised entrepreneur and the franchiser. The work of Nerilee HING (1993, 1995) demonstrates clearly the importance of initial steps toward the choice of a franchise. In reviewing franchising literature, several types of reasons for choosing a franchise can be observed (see table 1).

|

Reasons for choosing franchise |

Authors |

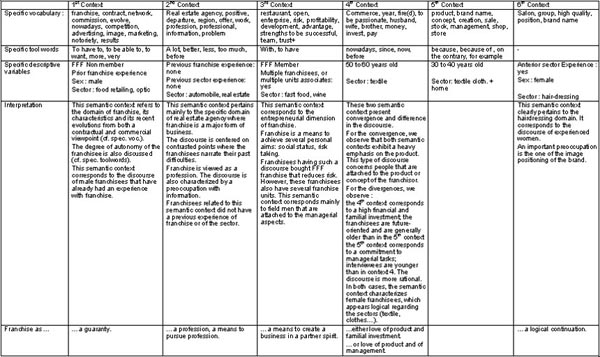

Type of contribution |

Method |

|

Brand (known trade name) Assistance before and after opening of the business |

HUNT (1977) |

Theoretical |

- |

|

Known trade name More independence than salaried employment Greater job satisfaction Less risky than independent business More profitable than independent operation Quicker business development |

KNIGHT (1986) |

Empirical |

Mail survey |

|

Training Independence (compared to salaried work) Established name Low development costs (compared to independent business) High profitability Low operational costs (compared to independent business) Less of a commitment (than independent business) |

PETERSON & DANT (1990) |

Empirical |

Mail Questionnaire |

|

Proven business format Less risky (than independent business) Goodwill (possibility to make profit) Start-up support (when starting the business) On-going support (when running the business) Quick start (because of proven business system) Gain some experience (in management or in the sector) Personal liking More money (than salaried work or than independent business) Fad |

WITHANE (1991) |

Empirical |

Mail survey |

Table 1: List of the reasons for choosing franchise drawn from the franchise literature [7]

Patrick KAUFMANN and John STANWORTH (1995) suggest that decision criteria can often be categorized by using a double comparison: (1) franchise vs. salaried employment and (2) franchise vs. independent business. Indeed, all elements of table 1 fall into one of these two dichotomies. [8]

Existing lists of criteria for choosing franchise are often inspired from previous research, hence the lists are not necessarily renewed and actualized. It is also noticeable that these lists of reasons have been used exclusively in English-speaking countries (UK, Australia, and USA). Certain authors (STANWORTH & CURRAN, 1999) recently acknowledged that there is still a debate concerning the motivations of the entrepreneur who chooses a franchise. While some authors have assimilated the franchisee to an ordinary entrepreneur, seeking profit maximization, others indicated that franchisees' choice is mainly driven by self-actualization and risk aversion. They state (STANWORTH & CURRAN op. cit., p 335): "At the heart of the above debate lies the issue of precisely where, on a continuum ranging from self actualizing on the one end to profit maximizing on the other, the franchisee resides." These authors then call for research propositions reflecting the high complexity of franchisee motivations. [9]

Consequently, there are two main objectives assigned to this research. Firstly, although there exists research centered on the selection process of franchise, information sources and motivations (see table 1 above); the fact that a new field, the French one, is investigated requires a preliminary exploration. Hence, the first objective of this research is to understand French franchised entrepreneurs, and to grasp their motivations. Secondly, apprehending choice criteria of franchisees necessitates that open qualitative interviews are used so that people can express their own story. The complexity of the choice of franchised entrepreneurs recently acknowledged by franchise researchers (STANWORTH & CURRAN op. cit.) also provides a strong rationale for using qualitative interviewing. Our objective was thus to generate a richer analysis of choice process as compared to conventional surveys with close-ended questions. This qualitative exploration can also help to see if existing lists of reasons for joining franchise need to be enriched. [10]

The research team was composed of four researchers: three women and one man. The work began with a common literature review that helped to circumscribe the franchise area (ARONSON 1994). Next, a common interview guide was developed which was to be used by the four researchers in carrying out semi-structured interviews (see Appendix 1). [11]

Twenty interviews were conducted in 4 different regions of France with 21 individuals.1) The objective of the guide was to encourage interviewees to narrate their experience from the moment when they decided to purchase a franchise (BERTAUX 1997). These interviews represented 24 different brand names. Ten different franchise sectors were investigated (estate agencies, fast food, optic, food retailing, automobile, clothes textile, hairdressing, wines, home textile, shoes). The sample consisted of 12 men and 9 women (see Appendix 2 for more details). [12]

The quality of interview data was maintained by several means. First, the research team developed the interview guide during several sessions. These sessions were aimed at clarifying what was the objective and what type of open-questions could be formulated. Once this step was completed, researchers became engaged conducting in the interviews. The interviews were not taped in order to keep a free, natural interaction with interviewees, field notes, hence were preferred. Each interview was summarized quickly after the interview in order to retain all the data and impressions that emerged during the interaction. The summaries were then sent via e-mail to other researchers. This was a way to ensure that all researchers were aware of what had been discussed in the interview even if they did not interview the same people. Lastly, interviewees checked the summaries. [13]

The overall corpus count was 13,687 words and the data analysis was conducted using two different types of methods. The overall process can be schematized as follows (figure 1).

|

ID Number of interview Shop sign FFF (French Franchise Federation) or Non FFF Sector Number of franchise Number of shops Number of associate |

Town Date Interview length Age Sex Previous experience of franchise Previous experience of sector |

Figure 1: Interpretative process [14]

Concerning the analyses, two parallel sessions were performed. On the one hand, two researchers realized separately a content analysis (BARDIN 1993). They extracted main themes from the interviews and confronted their results. On the other hand, a statistical textual analysis was conducted with specific scientific software (ALCESTE, University of Toulouse, France). [15]

Statistical Textual Analysis is grounded on lexicometrics. The basic hypothesis is that language levels and texts' structure can be inferred from recurrent distributions of words. The software used in this study (ALCESTE) is based on three approaches: lexicometrics, "content analysis" and data analysis (LESCURE 1999). [16]

Lexicometrics was used to count each word and form. Content analysis was used in a specific form: it helped to cut the text into sequence of sentences, delineating what is called a Context Unit (CU). A CU is defined as a number of words per unit. The meaning of CUs is independent from the cutting process. Lastly, data analysis, more precisely cluster analysis, is used in order to structure the corpus after its cutting. The cluster analysis uses the presence/absence of words in order to construct the clusters (Chi-square statistic). In the results outputs, the researcher can verify that a word or a form (i.e.: modal verbs, geographical indications ...) is significantly associated with a cluster or another. [17]

Each cluster is characterized by (1) its specific vocabulary, (2) its specific toolwords, (3) its specific descriptive variable. Each cluster can be understood as a specific "semantic context" that can be utilized in the discourse of any interviewee. However, certain interviewees might preferably use one or another semantic context. In addition, researchers can specify descriptive variables. Table 2 shows the variables used in order to characterize interviews.

|

ID Number of interview Shop sign FFF (French Franchise Federation) or Non FFF Sector Number of franchise Number of shops Number of associate |

Town Date Interview length Age Sex Previous experience of franchise Previous experience of sector |

Table 2: Descriptive variables for the interviews [18]

Once the semantic contexts were identified by the statistical textual analysis, two researchers (C & D) interpreted the results individually and compared the convergence of their interpretation. This double procedure makes sure that interpretations are not a collective groundless reconstruction but rather a dialectical field-grounded one. [19]

Several researchers advocate the merits of combined approaches in research (EISENHARDT 1989, NAU 1995, TASHAKKORI & TEDDLIE 1998). The present research uses triangulation at two levels. First of all, "methodological triangulation" is performed through statistical textual analysis and thematic content analysis. Both methods are used on the same data set. Secondly, "investigator triangulation" is achieved as two researchers work with each of these methods and then compare their results and interpretation. The procedure yielded the following results. [20]

4.1 Results of the thematic content analysis

The thematic content analysis led to identification of two ranges of reasons: (1) reasons for choosing franchise and (2) reasons for choosing a specific brand. The two researchers (A & B) who separately extracted the themes listed the same types of reasons, which is an indication of convergent validity. Compared to existing lists of reasons widely used in franchise research (HUNT 1997, KNIGHT 1986, PETERSON & DANT 1990, WITHANE 1991), additional reasons for joining franchise were found (see table 3).

|

Classical reasons |

Additional reasons |

|

Security of the business formula (brand, training, advertising, advice) Efficiency of the franchise formula as compared to other forms of business Independence coupled with risk reduction Business development and growth Limited initial investment |

Valorizing activity (successful status) Reconversion (in case of fired people) Source of revenue Professional promotion Possibility to be geographically settled Opportunity |

Table 3: Classical and additional reasons for joining franchise [21]

Additional reasons that were mentioned by interviewees reflect mainly two types of elements: (1) the evolution of economic situation and (2) the (French) national culture. First, current lists of reasons need to be updated by including the unemployment phenomenon: a certain number of franchisees decide to buy a franchise in order to pursue a professional activity and to have a source of revenue. In such cases, the "entrepreneurial spirit" (that is cited as a classical reason to choose to franchise) is not a pivotal incentive for these individuals to choose franchise. Unemployment hence has a fearful effect; individuals mainly seek to earn money in the future. Second, franchise is restricted to a defined geographical area which appeals to the French as they are not known for being very mobile, and this is partly reflected in the reasons for choosing franchise. [22]

The two researchers also identified the reasons for joining one specific franchiser or type of franchise (see table 4). Reasons can be either linked to one specific franchiser or to the type of business or the environment.

|

Franchiser specific reasons |

Contextual reasons |

|

Reputation Financial health Human size Competitive position Fit between franchiser culture and discourse and the franchisee personal values Trust in the franchiser's concept Trust in encountered people, good contact Possibility to open a store in the desired area Cheap investment |

Sector's dynamism Affinity with the sector Fit between sector and initial training Previous experience in the sector (either through salaried employment, or through independent business) Opportunity |

Table 4: Reasons for choosing the franchiser [23]

Certain franchisees were clearly attached to one specific franchiser because of a good contact, because of an attachment to the product or concept, or because of rational economic reasons. Others franchised entrepreneurs could have chosen one or another franchiser. For them, the most important factor is not the franchiser itself but rather the context. [24]

This first content analysis is interesting for several reasons. Firstly, it shows that the reasons for joining franchise have evolved over the last decade. Indeed, most of the lists describing the reasons for choosing franchise were determined a decade ago. Secondly, it helps to renew and complement the potential lists of reasons. Thirdly, it exhibits national differences. The fact that French are not very mobile shows such national specifics (mainly, compared to US). Fourthly, it demonstrates the importance of the franchiser's characteristics: contact, inspired trust, concept / product quality, reputation ... [25]

4.2 Results of the statistical textual analysis

The statistical textual analysis helps to quantify the importance of themes and to categorize different types of choice process. In a first step, a simple count of words is made (see table 5) which allows for the identification of the most frequently used words.

|

Franchise network make shop, store advertising, notoriety, image work shop sign / result, profitable, turnover / choice sector product agency / create trust, concept group / know / estate think / information / satisfied / sale exist/ see / important / restaurant / person opening commerce / first / relation / law / team / brand enterprise / commission / follow / departure / profession / pay / action total / contract / consider / independent / offer / unique |

Table 5: Most frequent words (descending order) [26]

From a vocabulary standpoint, several observations can be made. Firstly, as can be expected, the word "franchise" (and its derivatives: franchisee, franchiser, franchised ...) is the most frequent word as this is the topic of interviews. Secondly, our interviewees use three different vocabularies. The first one refers to juridical words: franchisees mention the contract and the legal relationship that links them to the franchiser. In this domain, certain of them are relatively critical. The second type of vocabulary that is used pertains to business management. Franchised entrepreneurs speak of finance, marketing and human resource management (training, support). The last type of vocabulary entails franchise as compared to other forms of business but also franchise in itself as an advantageous business system. Franchised entrepreneurs feel reassured to be part of a group (the franchise system), part of a whole system. The fact that they are not alone and that they can rely on the franchise network is important for them. [27]

Following the ALCESTE analysis, six semantic contexts are identified. Each semantic context is characterized by: (1) its specific vocabulary, and (2) its specific descriptive variable (listed in table 2). For each semantic context, two researchers (C & D) separately conduct their analysis and interpretation. Since the interpretations were convergent, the following table merges the two. [28]

ALCESTE also provides a correspondence analysis with two principal axes; it exhibits sharp oppositions in discourses depending on the franchised entrepreneur's characteristics. Mainly, male franchisees with no experienced of the franchise sector have a very different discourse from female franchisees with a strong experience of the franchise sector (here the hairdressing sector). Also, multi-franchisees (franchisees with more than one shop with one or more franchiser) do not have the same discourse as franchisees possessing only one shop. These two oppositions structure partly the six categories that are described in table 6.

Table 6: Semantic contexts description. Please click here for an increased version of Table 6 [29]

The statistical textual analysis categorizes different selection process. Six different categories of reasons appear: safety, professional activity, attachment to the product (with 2 different variants), entrepreneurial objectives, or even logical continuation. Again, it should be stressed that the identified categories are not clusters of franchisees. There are "types" of discourses, semantic contexts that certain interviewees adopt more or less tightly. When referring to the raw material (i.e.: the interviews summaries) additional explanations can be made concerning the six semantic contexts. [30]

The context 1 describes the advantages of franchise and the securing elements it provides. The network form is perceived in itself as a strength in the current economic situation. [31]

The context 2 describes professional changes. These changes appeared through two different forms. Change can be a desired outcome for certain franchisees who actually choose to become franchisee at one point of their life. But change can also be involuntary for others who were obliged to create their own employment through franchise. In both cases, franchise is perceived as an opportunity. [32]

The context 3 reflects the independence preoccupation. It can be viewed as the entrepreneurial dimension of franchise. However, the profile of franchisee does not equate to pure entrepreneurs because they are also aware of the fact that risks are reduced. This risk reduction is linked to the partnership that results from the contract between franchiser and franchisee. [33]

The context 4 corresponds to a discourse where there is a high, almost affective, involvement in the franchiser's product. The financial aspect of the initial investment is important for the franchisee who does not seek to possess more than one shop. Franchise provides an exciting professional life, support, and life comfort. The familial dimension (i.e. the possibility to work with family members) is also deemed crucial. [34]

The context 5 also reflects the passion for the franchiser's product or concept. The franchisees that predominantly develop this discourse are looking for training and support in managerial tasks that they also appreciate. Franchise provides a means for achievement and ambition is well developed. Most of the franchised entrepreneurs characterized by this discourse possess several shops, with different franchisers. [35]

The context 6 corresponds to the hairdressing domain, which is relatively specific. Indeed, franchisees in that domain are highly skilled, and some of them acquired their skills thanks to a professional evolution within the franchiser organization. This is why investing in a franchise unit of the franchiser's brand name appears quite logical. Franchise therefore corresponds to a progressive social ascension. [36]

As noted before, each interviewee can use one or several semantic context. The example of interviewee #11 illustrates this point (see table 7).

|

0011 *sect_textil *age_50-60 *sex_fem *expfranch_non *expsect_oui CU186(4) CU187(4) CU188(4) CU189(4) CU191(4) CU194(4) CU195(4) CU198(5) CU199(4) CU202(4) CU203(5) Legend: CU186(4) should be read as follows: context unit #186 belongs to semantic context #4. |

Table 7: Interviewee #11 and semantic contexts [37]

Interviewee 11 is a woman between the ages of 50 to 60 years; her franchise outlet is in the textile sector. She never had any franchise experience before but was familiar with the sector. As shown, she mainly uses the 4th semantic context, the one that corresponds to franchise seen as "love of product and familial investment". Parallel, to a certain extent, she also sees franchise as a means to develop managerial skills (5th semantic context). [38]

Overall, we identified six types of motivations for buying a franchise. It can be concluded that the reasons are very varied. Moreover, the choice of franchise does not correspond to a monolithic choice process. The desire to invest in franchise stems from very different life courses and several motivational factors can overlap one another. This is summarized in the following figure.

|

Entrepreneurial spirit & search for independence Professional change & opportunity Security & stability of the business formula Product attachment & familial accomplishment Product attachment & search for managerial support and training Logical continuation and social promotion |

→ Choice of franchise |

Figure 2: Multiple motivations to become a franchisee [39]

Compared to previous knowledge about franchisees' reasons to choose franchise, this study brings important findings. Firstly, it points out that the classical dichotomies (salaried employment vs. franchise and independent business vs. franchise) are not unique explanations for choosing a franchise. This important result is linked to our research process. Had we designed the interview guide with questions involving contrast between salaried employment and franchise on one hand, and independent business and franchise on the other hand, we would have found the same type of categories as previous research. Focusing on franchise solely was hence very fruitful. [40]

Secondly, existing lists of motivations for franchise buying need to be enriched by: (1) current economical developments and (2) national culture differences. This shows that exploratory qualitative research is relevant, if not necessary, in the field of franchise. Particularly, we think that this is important when investigating new fields (the French field had never been studied before concerning the topic of the franchised entrepreneur's motivations). [41]

Thirdly, the results suggest that a distinction should be made between the choice of franchise and the choice of franchiser. Neglecting this aspect could be misleading when analyzing franchisees' motivations. This is particularly important from a managerial point of view. Indeed, certain franchisers might appear very attractive for potential franchisees because of their intrinsic characteristics. And this is important to understand and to know as a franchiser, as it is a key element for franchisees' recruitment. [42]

Fourthly, our study supports the idea that choice process is not a monolithic one. Six different representations of franchise were identified. These representations drive the franchisee's motivation. Moreover it is important to underline that, at the individual level, these representations (semantic contexts) are not exclusive from one another. Rather several representations can concur to the decision of buying a franchise. [43]

Overall, the findings help to get out of simplistic dichotomies. They flesh out franchising research and lead to the acknowledgment of the complexity of real life. [44]

This exploratory research aimed at grasping the motivations of French franchised entrepreneurs to buy a franchise. It proceeded with open interviews with 21 franchisees from different parts of France. Two methods of analysis were used in order to guarantee objectivity. This procedure was reinforced by a double interpretation within each method. [45]

The present study is not free from limitations. First, the methodological choice to summarize the interviews rather than tape them introduces a certain distortion as there is a potential loss of information. Hence field notes cannot be strictly assimilated to franchisees' discourse. Second, working in a research team is both a strength and a weakness. The strength lies in the richness of the analysis but the weakness pertains to the possibility of several individual bias, although we tried to minor them. Lastly, we had the view of franchisees but we were not able to establish how these motivations were formed. The interviews took place once the decision had already been made and not during the period when the franchisees were in the process of selecting a franchise. Hence, further research would be needed for (1) establishing more firmly our findings and (2) developing a more thorough understanding of franchised entrepreneurs' discourse. [46]

Additional investigations with confirmatory purposes could be interesting. Precisely, linking more systematically the discourse about motivations and the specific background of franchised entrepreneurs would be of high value. Second, mixing data sources from new franchisees, franchisers, and documents could reinforce and widen conclusions. It is possible, for instance, that franchisees' motivations reflect the arguments developed by franchisers for recruiting new franchisees. This would allow to understand potential interdependence effects across discourses and perceptions. Overall, our results constitute a first insightful step toward a better understanding of franchisees' choice process. [47]

This research was funded by the French Franchise Federation. The author thanks her colleagues, Dr. N. DUBOST, Dr. V. GUILLOUX, and Pr. KALIKA, for their participation in the research. She also thanks FQS reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

How did you come the idea of franchise?

Do you have several franchise outlet, which ones?

What did you do before?

How did you know about this franchiser?

When?

Tell me how you choose your franchiser?

What were the most important factors?

Did you hesitate between different business formulas? Between franchisers?

What were you looking for in a franchise?

Did someone advise you?

Appendix 2: Brief description of interviewees

|

interview |

gender |

sector |

outlet |

franchisers |

associates |

Prior exp of franchise |

Prior exp of sector |

|

1 |

man |

r-estat |

1 |

1 |

2 |

yes |

no |

|

2 |

man |

r-estat |

1 |

1 |

1 |

no |

no |

|

3 |

man |

F food |

3 |

1 |

1 |

no |

no |

|

4 |

man |

F food |

1 |

1 |

1 |

no |

no |

|

5 |

man |

Optic |

5 |

1 |

1 |

yes |

yes |

|

6 |

man |

Optic |

3 |

1 |

1 |

yes |

yes |

|

7 |

man |

Food retail |

1 |

1 |

1 |

no |

yes |

|

8 |

man |

Auto |

2 |

1 |

1 |

no |

no |

|

9 |

wom |

Auto |

1 |

1 |

1 |

no |

no |

|

10 |

wom |

r-estat |

1 |

1 |

1 |

no |

yes |

|

11 |

wom |

Textil |

1 |

1 |

1 |

no |

yes |

|

12 |

wom |

Hairdres |

1 |

1 |

1 |

no |

yes |

|

13 |

man |

Optic |

1 |

1 |

1 |

no |

yes |

|

14 |

wom |

Textil |

1 |

1 |

1 |

no |

no |

|

15 |

wom |

Textil |

1 |

1 |

1 |

yes |

yes |

|

16 |

man |

Food |

7 |

2 |

3 |

no |

yes |

|

17 |

wom |

Textil |

1 |

1 |

1 |

no |

no |

|

18 |

wom |

Textil |

6 |

4 |

1 |

no |

no |

|

19 |

man |

r-estat |

1 |

1 |

1 |

no |

no |

|

20 |

wom |

hairdres |

1 |

1 |

2 |

no |

yes |

1) One interview was conducted with 2 interviewees who were working together in the franchise. <back>

Alceste User's Guide (2000). University of Toulouse, France, http://www.image.cict.fr/alceste.html [Broken link, September 2002, FQS).

Aronson, Jodi (1994). A Pragmatic View of Thematic Analysis. The Qualitative Report, 2(1), http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/BackIssues/QR2-1/aronson.html.

Bardin, Laurence (1993). L'analyse de contenu. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France Le Psychologue.

Bertaux, Daniel (1997). Les récits de vie. Sociologie 128 Series. Paris: Nathan.

Elango, B. & Fried, Vance H. (1997). Franchising Research: A Literature Review and Synthesis. Journal of Small Business Management, July, 68-81.

Eisenhardt, Kathleen.M. (1989). Building Theory from Case Study Research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532-550.

Hing, Nerilee (1993). Contributors and Consequences Relating to Franchisee Satisfaction in Australian Restaurant. Phd Thesis, University of New England-Northern Rivers.

Hing, Nerilee (1995). Franchisee Satisfaction: Contributors and Consequences. Journal of Small Business Management, April, 12-25.

Hunt, Shelby D. (1977). Franchising: Promises, Problems, Prospects. Journal of Retailing, 53(3), 71-84.

Kaufmann, Patrick J. & Stanworth, John (1995). The Decision to Purchase a Franchise: A Study of Prospective Franchisees. Journal of Small Business Management, October, 22-32.

Knight, Russel M. (1986). Franchising from the Franchisor and Franchisee Points of Views. Journal of Small Business Management, July, 8-15.

Lescure, Pierre (1999). Synthèse de la méthodologie Alceste (Alceste Training Program, Société Image, Toulouse).

Morrison, Kimberley A. (1997). How Franchise Job Satisfaction and Personality Affects Performance, Organizational Commitment, Franchisor Relations, and Intention to Remain. Journal of Small Business Management, July, 39-63.

Nau, Douglas S. (1995). Mixing Methodologies: Can Bimodal Research be a Viable Post-positivist Tool? The Qualitative Report, 2(3), http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR2-3/nau.html.

Peterson, Alden & Dant, Rajiv P. (1990). Perceived Advantages of the Franchise Option from the Franchisee Perspective: Empirical Insights from a Service Franchise. Journal of Small Business Management, July, 46-61.

Stanworth, John & Curran, J. (1999). Colas, Burgers, Shakes, and Shirkers: Towards a Sociological Model of Franchising in the Market Economy. Journal of Business Venturing, 14(4), 323-344.

Tashakkori, Abbas & Teddlie, Charles (1998). Mixed Methodology – Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Applied Social Research Methods Series, Volume 46. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Withane, Sirinimal (1991). Franchising and the Franchisee Behavior: An Examination of Opinions, Personal Characteristics, and Motives of Canadian Franchisee Entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, January, 22-29.

Young, Joyce A.; McIntyre, Faye S. & Green, Robert D. (2000). The International Society of Franchising Proceedings: A Thirteen Year Review. Proceedings of the 14th Annual International Society of Franchising Conference, San Diego, pp.91-98.

Claire GAUZENTE is an Assistant Professor in Marketing and Organization at the University of Angers, France. She is also a Visiting Professor at the Southampton Business School, England. Her interests include market orientation, organizational culture and inter-organizational dynamics.

Contact:

Claire Gauzente

LARGO – Faculté de Droit, Economie et Gestion, Université d'Angers, France, 13 allée F. Mitterrand, BP 3633, 49036 ANGERS cx 1, France

Phone: (33) 241 96 21 75

E-mail: claire.gauzente@univ-angers.fr

Gauzente, Claire (2002). Using Qualitative Methods in Franchise Research—An Application in Understanding the Franchised Entrepreneurs' Motivations [47 paragraphs] Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(1), Art. 20, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0201208.

Revised 6/2008