Volume 3, No. 1, Art. 1 – January 2002

The Application of Mindfulness Meditation in Mental Health: Can Protocol Analysis Help Triangulate a Grounded Theory Approach?

Oliver J. Mason

Abstract: The methods of Grounded Theory and Protocol Analysis were triangulated in a study of mindfulness meditation as used by participants with a history of depression. Protocol analysis is an empiricist qualitative method (with an element of quantification) that has received little attention as a source of triangulation with other qualitative approaches such as grounded theory. Protocol analysis was applied to data collected using a "talk aloud" technique applied to a period of instruction-based meditation. The reliability of a simple coding system was encouraging and suggested that task-related mental activity can be coded at a simple descriptive level. The results of protocol analysis were discussed in the light of categories derived from a grounded theory account described elsewhere. The degree of correspondence and mutual support was striking in two ways. First, participants' experiences were mirrored in the two methods. Second, several categories from the theory were elucidated and exemplified by the protocol results. Some of the potential difficulties of comparing results from different methods were discussed. An additional limitation was that further quantification of the protocols' code categories was not possible. However, it was suggested that testable hypotheses could be derived from future theory development so as to use protocol analysis as a more formal test of the theory.

Key words: protocol analysis, triangulation, mental health, grounded theory

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

1.1 A qualitative approach to studying the use of meditation in mental health treatment

1.2 Protocol analysis

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

2.2 Protocol analysis

2.3 Grounded theory

3. Results

3.1 Reliability and validity of protocol analysis

3.2 Triangulation points

3.2.1 Pain, and the sense of desire

3.2.2 Skills related to thinking

3.2.3 Visualisation

3.2.4 Discovery and surprise

3.3 Process in the grounded theory

4. Discussion

4.1 Comments on protocol analysis

4.2 What is the purpose of triangulation?

The notion that the comparison of methods as applied to an object of scientific investigation, or triangulation, could support the validity of research findings was first introduced in a quantitative context by CAMPBELL and FISKE (1959). Its application has subsequently generalised to qualitative approaches (DENZIN, 1970), and has become an important concept in supporting the trustworthiness of qualitative analysis (BANISTER, BURMAN, PARKER, TAYLOR & TINDALE, 1994). Within a broadly "realist" tradition of qualitative research, triangulation has been suggested as a way of converging on robust findings from diverse approaches so as to "partial out" biases inherent in any one approach, or as a validity check (MILES & HUBERMAN, 1984). Other more constructivist or post-modernist researchers find this attempt to ascertain an objective "truth" questionable, and indeed deeply faulted (YARDLEY, 1997). Rather than confirming or disconfirming accounts, this approach would suggest that triangulation supports the credibility of analytic products (ROBSON, 1993), and has the strength of furthering reflexivity in relation to methods and their inevitable biases. I take the position in the present research that a form of weak realism is possible, in so much as participants have an awareness of sensations and thoughts during meditation and can report on them with some degree of correspondence. This is not to deny that culture and language are important influences on participants' experiencing, interpreting and reporting, as well as the researcher's interpretations; nor to claim that a comparison of methods can in some way exclude the inherent subjectivity of reporting or the biases of method and researcher. [1]

There are few guidelines for the use of methodological triangulation and I was forewarned of several areas of potential difficulty (MITCHELL, 1986) that I reflected on during the research process. In particular, could numeric data about the frequency and co-occurrence of coding categories be merged with textual data; and how would divergent results be interpretable? Following the advice of MORSE (1991), I viewed triangulation as "a method of obtaining complementary findings that strengthen research results and contribute to theory and knowledge development" (p.122). As this was fresh ground for both methods, I took an inductive approach to studying the process by which the results of two qualitative methods could be meaningfully compared, and to what extent "triangulation" might be possible and plausible. [2]

1.1 A qualitative approach to studying the use of meditation in mental health treatment

Meditation approaches to treating individuals with mental health problems are receiving increasing attention and interest. This includes their use as an adjunct to therapy (LINEHAN, 1993), a relapse prevention strategy (TEASDALE, SEGAL & WILLIAMS, 1995) and as psychotherapy-in-itself (KABAT-ZINN et al., 1991) for a wide range of mental and physical health problems. Elsewhere (MASON & HARGREAVES, 2001), I reported on the application of a grounded theory approach to describing the accounts of participants with a history of depression following a course of mindfulness meditation taught by members of an adult mental health team. Several categories emerged that described the many ways in which participants understood the approach, practised the skills being taught, and located the "treatment" within their own lives and personal difficulties. I was keen to examine ways in which the accounts of participants and the understanding I had of them could be validated by other methods. [3]

Meditation is perhaps rare (though not unique) among phenomena suitable for qualitative enquiry in that data can also be obtained while the participant is engaged in the activity itself. The method of "talking aloud" (SOMEREN, BARNARD, & SANDBERG, 1994) is intended to facilitate the "on-line" reporting of mental contents during a period of meditation itself. With this aim in mind, I designed a method based on the "talk aloud" method—reporting mental contents whilst meditating—to supply verbal data that could be compared with participants' accounts at interview. [4]

Protocol analysis is a qualitative method (see GILHOOLY & GREEN, 1996) that may be applied to results from "talk aloud" so as to categorise verbal behaviour elicited during completion of a task. It has received little attention as a source of triangulation with other qualitative methods such as grounded theory. The results of this procedure (protocols) can be coded so as to provide a quantitative estimation of the method's reliability. In the present study, the results of the protocol analysis were used to triangulate with the grounded theory. "Think aloud" reports are usually obtained as an individual performs a cognitive or, more broadly, "thought-involving" task such as problem-solving. In reviewing the literature, ERICCSON and SIMON (1984) distinguished the process of articulating material that is in focal attention, from that of reporting thoughts and other meta-cognitive outputs that are not in focal attention. They concluded that the former can be reported with a high degree of accuracy, and that this does not affect problem-solving speed or accuracy. It is important that verbalisation is concurrent with the task and is not introspective or retrospective (as this is open to memory influences). "Thinking aloud" is different to introspection in that participants are explicitly asked not to supply theories about their cognitive processes, but rather to report their content. The issue of the validity of this method is a thorny one if a researcher wants to make claims about the completeness of these accounts. Clearly, material that is largely below threshold for conscious awareness will be incompletely reported if at all. However, this complaint is irrelevant if the subject of interest is to obtain a self-report of the contents of current awareness. [5]

Protocol analysis has largely been applied in the context of problem-solving and other fields of cognitive science. More exceptionally, "think aloud" techniques have been applied to topics including dreaming (FOULKES, 1978), women's sex roles (CONDOR, 1986), film watching (MAGLIANO DIJKSTRA, & ZWAAN, 1996), creative processes in art and writing (RUSCIO, WHITNEY & AMABILE, 1998), and a professional actor's role preparation (NOICE & NOICE, 1994). In these contexts (and perhaps all) we should acknowledge that protocols will be heavily influenced by expectations of both the participant and the researcher, as well as the language and culture surrounding the topic. This is to say that the results of protocol analysis are not the "truth" against which to test other methods, but are just as influenced by the context in which they are derived. [6]

Participants were thoroughly briefed about the study and invited to take part by the author using an information and consent form. I had completed the meditation course both prior to the study and with the participants themselves in the context of a treatment available from mental health services. Eight participants consented to participate: Pam (38) had a three year history of M.E. (colloquial for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome) and had been referred for anxiety and depression. Jane (44) had suffered depression following a difficult illness and had received psychotherapy from services. Lucy (34) had suffered several episodes of depression both during and since an acrimonious divorce, and had also received psychotherapy. Mary (24) was diagnosed with M.E. over a year previously, had been referred to mental health services, but had not received any psychotherapy prior to the course. Carys (59) had suffered several episodes of depression over the previous six years associated with her own successfully treated cancer and the loss of her sister through the same illness. Mark (54) had suffered depression on several occasions associated with divorce and maternal bereavement. He had received both behavioural therapy and transactional analysis (TA) therapy in the past. Robert (49) reported that his problems with depression began over eight years ago, but that he had not received diagnosis until later, and has received anti-depressant treatment on a few occasions. Adrian (32) was diagnosed with a paranoid psychosis over six years ago. He has suffered frequent paranoid ideation and obsessive-compulsive behaviour coupled with depression in the intervening period and had considerable input from mental health services. [7]

Two participants did not want to participate in the "think aloud" meditation. In the case of one (Lucy), this was due to time constraints. In the case of the other (Carys), the interview had reminded her of difficult past experiences and she did not want to continue after the interview. [8]

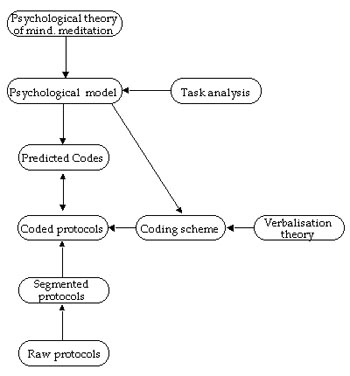

Study of the process of protocol analysis (see Figure 1) led this researcher to consider creative ways to overcome difficulties with the psychological model and the coding scheme.

Figure 1: Overview of protocol analysis (after SOMEREN et al., 1994) [9]

SOMEREN et al. (1994) point out that the verbalisation theory (which specifies how thoughts will be verbalised) cannot usually specify codes directly, and piloting of protocols is necessary to construct the rules by which a coding scheme may be applied. One such coding scheme based on a psychodynamic theory (FOULKES, 1978) attempted to make inferences about unconscious processes such as repression and denial to study protocols of dreaming. [10]

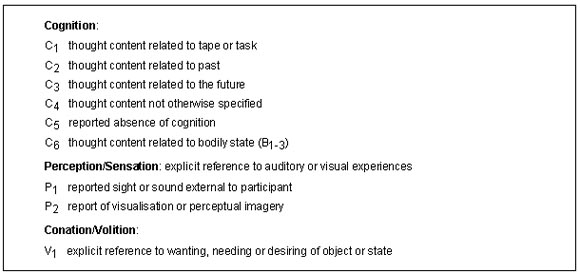

In contrast, I did not utilise any explicit psychological theory such as a cognitivist or psychodynamic account of mental processes. Rather I used a generic model of psychological states or processes to generate the coding system based on the explicit reported content (see Table 1). The vocalisation theory required explicit phrasing: for example such the use of a verb such as "to need", "want", or "hope" would be required to code for "conation/volition".

Table 1: Protocol Codes [11]

Prior to the meditation exercise, a warm-up exercise was used (see SOMEREN et al., 1994) in which the participant was instructed to invent five improvements for various domestic appliances. For the task itself, the specific instructions were to "say whatever you are currently aware of out loud" when prompted by an auditory cue (a ringing bell). The method was clarified during the warm-up for participants that failed to report their thoughts in current awareness and instead introspected about the task, so that no further communication was required from the researcher during the "think aloud" meditation. During the meditation, participants were told to report the content of their moment-to moment awareness following a prompt at pseudo-random intervals of between 10 and 35 seconds. Following recommendations of ERICCSON and SIMON (1983), the researcher was placed out of view of the participant during the procedure and provided the auditory cues. All participants had used a standard meditation tape lasting twenty minutes as part of the course homework practice and were familiar with its use. Participants were instructed to use the tape just as they would at home and were shown the controls on a hand-held tape recorder. [12]

Open interviews with Pam, Jane, Carys and Mary lasted between one and one and a half hours each. The interviews were analysed following the guidelines of STRAUSS and CORBIN (1990). The products of this analysis, and the questions it prompted were used to guide four further interviews with the remaining participants. These were recruited from a group that continues to meet to share experiences of meditation and other course-related issues. The categories were re-appraised in the light of further coding from these additional interviews so as to attempt to reach theoretical saturation. Detailed descriptions of the categories are given elsewhere (MASON & HARGREAVES, 2001). [13]

3.1 Reliability and validity of protocol analysis

For the purposes of protocol analysis, the entire response to a single prompt was taken to be a segment. The coding system was applied to two protocols by the researcher and another coder independently. The kappa coefficient of reliability was calculated from both protocols. The resulting coefficient of 0.7 was formally sufficient but suggested further room for improvement. Codes used by one coder and not the other were entirely drawn from the "C" category related to cognition. Following discussion, we decided to specify that cognition would be coded for when explicitly referred to by verbs such as "thinking, analysing or wondering" as well as when mental contents were referred to in quantities sufficient to convince the coder that a thought process had occurred. In addition, both coders noted that "body-related cognitions" occurred in both protocols. We agreed to create an additional code (C6) specifically for this content. Following adoption of these revisions to the coding system and agreement on its application, re-calculation of the reliability coefficient produced a highly reliable estimate of 0.85. [14]

Because of concerns about the method's validity, following meditation, I asked participants about the impact of "thinking aloud". The majority of participants stated that it made no marked difference. Mark reported that he was able to achieve very much the same state of mind of "total awareness" as in his practice at home. Only Robert reported a disruption to his usual practice: he reported "[I] don't usually say anything in meditation, its a rather strange thing to do". Unfortunately, the "talk aloud" task appeared to have disrupted the usual pattern of his meditation. [15]

3.2.1 Pain, and the sense of desire

Mary, Pam and Jane reported frequent bodily sensations (B) and, in Mary and Jane's case, considerable pain. For both Pam and Jane, these codes occurred with those relating to willing (V1) and/or thinking (C2,3,4,6). At interview, Pam had talked of the "battle between body and mind", as she wanted to participate in daily activities more fully but was prevented from doing so. Interestingly, a sense of desire or wanting was present in her protocol—she said "I wish I could have as much energy as those girls outside" [audible talk heard from outside]: the codes in her protocol reflected the mental "battle" she described at interview. Mary had had a slightly longer history of meditation practice, and in her protocol "B" codes usually occurred alone and were only rarely paired with "C" and "V" codes. In keeping with this she reported at interview that she had previously fallen into the "trap" of "analysing what happens" but now could "just breathe and let go of thoughts". This mirrors the category of accepting attitude (see Appendix) that other participants have described. [16]

Jane and Mary responded in various ways to pain during the meditation. On the first occasion, Mary noted the back pain but did not act upon it: later she and Jane both practised "breathing into the pain". Following the meditation, Mary reported that "my back was hurting quite a lot so I was always brought back to that". These comments mirror their contributions to a category of skills (see Appendix): Mary stated how she had become "aware of how I am feeling while doing it [meditation]"; Jane said practiced bringing her attention back to her breath by "trying to dislodge my thoughts and put myself back with my breathing". [17]

3.2.2 Skills related to thinking

During the meditation, Pam reported many thoughts related to the past (C2), and referred at interview to "having a bit of pastitis". She explained after meditating that this was a chain of thoughts about the past that were associated with negative feelings. As part of her own clinical self-description, Pam had described how "you really notice what is happening in your thoughts". Later in the interview, she described how she had become able to identify thoughts as being thoughts rather than "thoughts-as-reality". [18]

At its conclusion, the tape suggests sitting "with majesty, the beauty of a mountain". Pam had previously expressed her preference for "visualisation" tapes, rather than tapes of the "just sitting there doing it" variety. Her propensity for visualisation was borne out by her immediate report following the suggestion that "I am the mountain". She later explained that this was a visual image that she invoked at that point. [19]

One of the categories that many participants contributed to suggested that meditation could engender moments of surprise (see Appendix) and, more rarely, discovery (see Appendix) that were important elements along their road to health. Intimations of the same were present in the protocols whether or not the meditation was perceived as a successful one or otherwise. For Robert, who felt the task broke up his meditational practice, the exercise "made me realise that I would like to do more regular, more sustained meditation, I really must do that, it reminds me of things I've forgotten". Adrian simply observed his thoughts, several sounds in the room and several bodily sensations throughout the meditation. Although this appears unexceptional, the meditation took place during a period of some paranoia and anxiety for him: he reported that he had felt unsettled and "not his usual self" following several days away from home—the first trip away in many years. Following the meditation he reported its effects as beneficial (see category of relaxation; see Appendix) and said he was surprised and pleased that he had felt able to sit throughout. [20]

3.3 Process in the grounded theory

Participants had varying levels of experience of mindfulness meditation and this contributed an important aspect of process to the grounded theory. Aspects of this process were present in the differences between the protocols of more and less experienced meditators. For both Mark and Adrian (more experienced), their protocols were characterized by their use of one and occasionally two codes for each segment. Although it is impossible to ascertain whether their current mental contents were more elaborate than that reported, it is probable that these experienced meditators restricted the contents of awareness more successfully than novices. [21]

4.1 Comments on protocol analysis

In this study, protocol analysis was piloted in a very simple form and demonstrated several methodological attributes; a) data can be collected during meditation; b) protocols can be coded reliably according to a simple system and; c) "think aloud" codes may validly reflect the current contents of awareness during meditation. Several caveats should be added to these attributes. The method requires careful preparation both in terms of instructions and "warming up" or practice. Even under these conditions, some respondents may find the method intrusive, thereby undermining its validity. Also, the coding system's reliability was improved by increasing the explicitness of codes. [22]

How complementary were the methods' results? In many respects the correspondence of "think aloud" contents with participants' contributions to grounded theory categories was striking. At the level of cognitive, affective and conative content, so to speak, the protocols substantiated what participants described during interviewing. However, the patterns of protocol coding and code content also went some distance to confirming the process of development illustrated in the inter-relationships among categories. Themes of "surprise", the influence of growing expertise and evidence of a discourse relating to spiritual development (see Appendix) also emerged in ways which "fleshed out" interview accounts in unexpected and interesting ways. [23]

4.2 What is the purpose of triangulation?

MORSE (1991) describes an important distinction between simultaneous and sequential methodological triangulation. In her terms, this study triangulates methods simultaneously as there is "limited interaction between the two data-sets during the data collection, but the findings complement one another at the end of the study" (p.120). This type of triangulation was well suited to the inductive nature of the research. It could be argued that a full integration of the results of the methods was not achieved. MITCHELL (1986) discusses the lack of consensus regarding guidelines for methodological triangulation. Although I have reported "think aloud" as a largely qualitative technique (apart from quantification of its reliability), it could be seen as deserving further quantification. Merging numeric information with the qualitative account derived from grounded theory would have proved difficult as MITCHELL (1986) has described. Formal numeric comparison of coding categories with the predicted model is often not possible and would be unlikely in the present context. [24]

The lack of previous theory and research meant that this project explored the phenomenon and developed concepts that may be faulty or biased. Part of the success of triangulation was that some confirmation was obtained, but future work could perhaps go further. As concepts and theories "mature", a more hypothesis-testing approach becomes possible and desirable. The protocol analytic approach is unusual in combining aspects of quantification with qualitative rigour. By quantifying protocols further, it could prove possible to evaluate other qualitative accounts in a quasi-experimental way. Several examples of this in the present context would be to examine the differences between novices and experts; as well as differences in the protocols of participants experiencing a variety of mental health difficulties. [25]

1. Accepting attitude

Many of the codes applied to products of the course did not address skills directly; instead these tapped a change in attitude towards acceptance, flexibility, and "living in the moment" (Pam). In keeping with the cognitive perspective that Pam had developed both before and during the course, she aimed to "acknowledge [thoughts] and not be bothered by them". For her, however, this remained a "self-management technique" rather than a more encompassing change of her attitude to life such as that suggested by Mary: "during the eight weeks I realised that it was possibly my attitude and the way I was running myself that led finally to the way I am". Instead, "through the mindfulness and acknowledging what is going on in the moment, be it birds singing or walking along ... you can start to enjoy life as it is happening rather than looking to the past or the future".

Jane also spoke of an attitude of trusting in the moment and reflected on the challenge this presents: "mindfulness is like if you live this moment, the future generally takes care of itself. Its a bit frightening at times ... does everything just fall into place?" This attitude "wasn't rigid in any way, don't put on any limitations, don't put yourself under pressure". Previously, she had avoided meditating in mornings as they were difficult. However, her attitude changed so that "after about the fifth session, I thought I will try it in the morning and just see ... I might derive some benefit for the rest of the day". She reported that the practice did help and became more regular as a consequence, so linking this attitude to her developing skills.

The issue of "acceptance" and just what this entailed provoked several comments. In the context of her medical difficulties, Jane said "the acceptance area is the hardest thing to accept, I struggle very strongly with that—I thought well I can't accept this; I don't want to accept what my life could be, you know, its um [pause] to me it was too terrifying, I struggle hard with that bit". Both participants suffering from M.E. also spoke about accepting their conditions. Mary said that she had learnt to alter her expectations so that "ts how you can be, not how you'd like to be". Pam also said that "nine days out of ten I do use the mindfulness and do accept it. I choose and I know what the consequences are going to be, but some days ... I am still anxious and depressed [pt. laughs]". Humour was a part of all of the interviews but is difficult to code and interpret. In several instances, it could be described as introducing a "distance" between the participant and their difficulties.

2. Skills

The course emphasised the development of skills both in practising meditation formally and informally such as by using breathing spaces. Most strikingly, participants differed greatly in their degree of success with different skills with breathing spaces, formal meditation and everyday application of mindfulness.

Jane reported of breathing spaces that "I didn't get the point at all" and found the practice very confusing. Mary reported that "through the breathing exercise they give you ... you know something's bothering you, you can't eradicate what's there, but you can acknowledge it so it can't take you over, it can't just happen automatically. You have a choice". Developing the use of breathing spaces led to a subsequent reduction in anxiety for her. Pam's use of the breathing space differed from Mary. Previously familiar with some cognitive behavioural literature, she described "counting to ten and pulling yourself together". Her interpretation of much of the course was one of helping her address negative thinking by "reminding yourself that it is not your fault" and mentally reciting "thoughts aren't facts ... even the ones that tell you they are". She described mindfulness as "going into yourself and exploring it". Mary also reflected on "analyzing what happens" during meditation, but suggested that this was in fact "another trap I fell into later". Instead, she felt that the skill is one of "just looking at what happens, not taking it to pieces trying to understand what's going on".

Mary described the skill she acquired from meditating by saying: "its a useful time to sit and lie and OK, the ... course teaches you to recognize what's in your head or acknowledge the fact ... OK I've got a problem, and if it comes back again, you look at it again, and if it comes back again—this is the way I do it—let's look at it properly ... why are you feeling scared, why are you feeling uncomfortable about it? I don't analyse it in a way, but I just sort of break it up a bit, so by saying I feel scared about it, I feel angry about it, just to myself ... it just disperses it". Carys also described a similar benefit from using the tapes: "because sometimes I don't sort of realise I might be thinking of something I don't realise, so when I sit down and do the tapes, I can actually work out what is worrying me, so that helps put it in perspective". When asked how she thought the breathing space worked, she said "the only thing I can think of is that my mind sort of wanders, that I am thinking of something else without actually being conscious of thinking about that"

There was some evidence that as practice progressed, mindfulness skills become incorporated into everyday living: Carys said "I use those little tips like using my breathing while I am waiting for the kettle to boil". For two participants this practice appeared to introduce a "distance" from their problems. In Robert's words:

"Its almost like you are outside of yourself looking at your mind working, its just that little separation, it doesn't happen all the time, but you can just step away, and that is intriguing, its like your mind watching your mind watching your body, its one step removed".

Similarly, Mark described how this skill helped at times of "mind overload":

"Its as if there is a switch in the mind now that goes, hang on, stop, be mindful, and we will start with this bit first. Its like an automatic correction that instead of getting bogged down with the mind trying to [pause] ..., its the ability to step back from that and hold the mind there. Just sort it out, just do one thing, I think that is the thing it does, it give focus all the time. Because it is easy to be swamped by whatever is on the mind.

I: And that ability remains even in periods of lowness?

M: It does, yes. I don't know what it does. It's so powerful, yet it is so simple. It's as if I have got two eyes. One is the one that interacts all the time, is automatic. And there is another one that I can go into and it's almost at the back here so that I am looking at myself, but its very intimate if you like, the border between it is very thin. And it is a very small eye, but a very powerful eye and it holds everything. And I can go to that point through mindfulness or meditation and hold or be with whatever happens. ... I lost my father last year so there was a lot of grief. And I was able to meditate with that grief and actually see it or feel it come up and allow it to come out, 'cos one of the problems I had was bottling things up. So I feel myself getting rather unhappy about losing my father, so I was able to sit quietly, allow it to come up and have a good cry. ... Its been a very valuable grief and a very pure one, and I now find that when I think of my father there is less a sense of loss and grief, and more a sense of honouring him".

3. Discovery/"Surprise"

For participants that described therapeutic gains, all described one or more points of discovery often with a sense of surprise. Jane said of her experience of mindfulness meditation that "it clarified a lot of things for me" and "I had a deeper understanding of what was going on ... what was causing the depression". She reported that this "wasn't always easy" and "brought additional problems" related to retrieving childhood memories. Mary described a process of discovery starting with the very first exercise of paying mindful awareness to the act of eating a raisin. This "opened her mind even more [than she expected] and was quite ... scary in a way, because it was realms I had never entered before". Later on in the course she made the discovery—"which I didn't realise until doing mindfulness"—that the sensations she felt in social situations of "getting really hot and starting shaking" were anxiety-related. This led to her taking action in the form of breathing spaces (see skills below). When asked about any surprises or discoveries he had made, Robert stated that "the key thing overall has been that often what goes through your mind are just mental phenomena, they are just thoughts not necessarily truths".

In addition to these points of understanding reached during the course, several described points of discovery either at the termination of the course or subsequently. Discussing termination, Robert said "I think we all felt that the carpet had been pulled from under us". Mark described his point of crisis at the end of the course thus:

"Its strange, that was so vivid, really incredibly difficult to describe the intensity of what I was feeling. It was as though I'd suspended all the problems I had had, anxiety and [pause] you know how your mind churns over problems, It was as if it had held them in abeyance for eight weeks, and then all of a sudden poof, I was lying in bed and I thought its OK, its OK to feel these things, and I think that was the thing about it, its OK to feel whatever you feel, they are not going to swamp the person".

4. Relaxation

Many reported one of the benefits of listening to tapes to be calmness or relaxation although this is explicitly not their stated aim. Jane reported that "it calmed me down a lot" and created "a space of calmness". Lucy reported her stated aim as relaxation, and her intermittent experience of this led to her re-commitment to practice at the end of the course. Unfortunately, as relaxation was not consistently forthcoming, she soon stopped this practice. At time of interview, Lucy intended to return to her practice "when I feel more relaxed" concerned that worries would prevent the relaxing effect she sought.

Given the aim is not relaxation per se, it was interesting that Robert described his experiences with the body scan tape as "perhaps too relaxing" although he noted that this is can be beneficial when stressed and finding sleep difficult. Interestingly, as the interview with Carys progressed, she realised that her meditation practice has different effects depending on her posture: "I think the lying down one, I think I take as a bit of relaxation, rather than the other one [using the stool] which Is doing meditating ... and I think that when I am feeling a bit stressed I use the stool more, which is something I haven't noticed before".

5. Spiritual Development

Three clients described how the course had led them to a sense of spiritual development. One had subsequently become a Buddhist and another had developed an interest in other meditation practices and was committed to personal daily practice. This theme emerged at the very end of interviews and would be an interesting focus of future work as there was no explicit "spiritual" content to any course materials, or indeed mention of Buddhism or other approaches to meditation during the course.

Banister, Peter; Burman, Erica; Parker, Ian; Taylor, Maye & Tindall, Carol (1994). Qualitative Methods in Psychology: A Research Guide. Buckingham; Open University Press.

Campbell, David T. & Fiske, David W. (1959). Convergent and Discriminant validity in the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56, 81-105.

Denzin, Norman (1970). The Research Act in Sociology. London: Butterworth.

Ericcson, Ken A. & Simon, Herbert A. (1996). Protocol Analysis (revised edition). Cambridge, Mass. MIT Press.

Foulkes, David (1978). A grammar of dreams. Hassocks, UK: Harvester Press.

Gilhooly, Ken & Green, Caroline (1996). Protocol analysis: theoretical background. In John T.E. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods for psychology and the social sciences (pp.55-74). Leicester, UK: BPS books.

James, William (1898). The Principles of Psychology. New York: Macmillan.

Kabat-Zinn, Jon; Massiou, Ann; Kristeller, John; Peterson, Lynne; Fletcher, Keith; Pbert, Lar; Lenderking, William & Santorelli, Saki (1992). Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program on the treatment of anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 936-943.

Linehan, Marsha (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press.

Magliano, Joseph P.; Dijkstra, Katinaka & Zwaan, Rolf A. (1996). Generating predictive inferences while viewing a movie. Discourse Processes, 22(3), 199-224.

Mason, Oliver J. & Hargreaves, Isabel (2001). A qualitative study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 9, 34-42.

Miles, Matthew B. & Huberman, A. Michael (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mitchell, Juliet (1986). Multiple triangulation: A methodology for nursing science. Advances in Nursing Science, 8, 18-26.

Morse, Janet M. (1991). Approaches to qualitative-quantitative triangulation. Nursing Research, 40, 120-123.

Nisbett, Richard E. & Wilson, Timothy DeCamp (1977). Telling more than we can know: verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84, 231-259.

Noice, Helga & Noice, Tony (1994). An example of role preparation by a professional actor: A think aloud protocol. Discourse Processes, 18(3), 345-369.

Robson, Colin (1993). Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers. Oxford, UK: Blackwells.

Ruscio, John; Whitney, Dean & Amabile, Teresa (1998). Looking inside the fishbowl of creativity: Verbal and behavioural predictors of creative performance. Creativity Research Journal, 11(3), 243-263.

Someren, Maarten van; Barnard, Yvonne & Sandberg, Jacogijn (1994). The Think Aloud Method: A practical guide to modelling cognitive processes. London: Academic Press.

Strauss, Anselm & Corbin, Julie M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Oakland, California: Sage.

Teasdale, John; Segal, Zindel & Williams, Mark, J. (1995). How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help? Behavioural Research and Therapy, 33(1), 25-39.

Yardley, Lucy (1997). Material Discourses of Health and Illness. London: Routledge.

Oliver J. MASON has a lecturing appointment at the University of Birmingham and is a clinical psychologist in South Birmingham. His interests include men's experience of illness and alternative therapeutic approaches to mental health.

Contact:

Oliver J. Mason

School of Psychology

University of Birmingham

Edgbaston, Birmingham, B15 2TT, UK

Tel.: 0121 414 3836

E-mail: o.mason.1@bham.ac.uk

Mason, Oliver J. (2001). The Application of Mindfulness Meditation in Mental Health: Can Protocol Analysis Help Triangulate a Grounded Theory Approach? [25 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(1), Art. 1, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs020119.

Revised 2/2007