Volume 2, No. 2, Art. 12 – May 2001

The Politics and Rhetoric of Conversation and Discourse Analysis: A Reflexive, Phenomenological Hermeneutic Analysis

Wolff-Michael Roth

Review Essay:

Ian Parker and the Bolton Discourse Network (1999). Critical Textwork: An Introduction to Varieties of Discourse and Analysis. Buckingham, England: Open University Press, 226 pages, ISBN 0-335-20204-7 (pbk) £16.99, 0-335-20205-5 (hbk) £50.00

Carla Willig (Ed.) (1999). Applied Discourse Analysis: Social and Psychological Interventions. Buckingham, England: Open University Press, 166 pages, ISBN 0-335-20226-8 (pbk) £16.99, 0-335-20227-6 (hbk) £50.00

Paul ten Have (1999). Doing Conversation Analysis: A Practical Guide. London: Sage, 240 pages, ISBN 0-7619-5586-0 (pbk) £16.99, 0-7619-5585-2 (hbk) £50.00

Table of Contents

1. Introduction-Producing Scene

2. Introduction-Producing Scene

3. Lecture on Reflexive Phenomenological Hermeneutic Analysis

4. Conversations with Authors

4.1 Talking about "talking about praxis"

4.2 The meaning of "meaning"

4.3 The absence of the body in writing

Supplement I: Ian Parker and the Bolton Discourse Network (1999). Critical Textwork

Supplement II: Carla Willig (Ed.) (1999). Applied Discourse Analysis

Supplement III: Paul ten Have (1999). Doing Conversation Analysis: A Practical Guide

Supplement IV: Writing a Review Article as Contingent and Historically-Situated Activity

Supplement V: Research and Writing as Contingent Activity

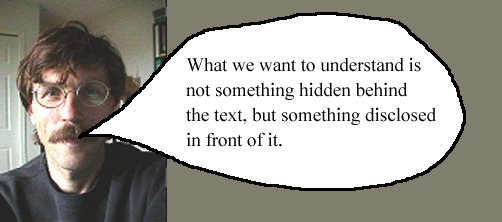

A way of acknowledging the author in the text, making him announce a major theme of this review article. In translated way,

the author also appears in the sidebar as a continuous reminder of his presence in the text and absence from the reading.

Quick but Dirty Definitions

Discourse Analysis: An Entry Point

Discourse analysis (DA) is a form of analysis that focuses on language above the level of single utterance. The term discourse is sometimes used to refer to patterns of meaning that organize the different sign systems used by humans as part of constructing and navigating their worlds. These signs may be viewed strictly in terms of verbal language or, as the Critical Textwork shows, in terms of the notion of sign more generally, that is, any pattern that the material continuum can take (including bodies, cities, film, images). DA attempts to "recover meaning" from the "texts" that encode these discourses.

Debby TANNEN: Discourse analysis [External link, broken, September 2003, FQS]

Conversation Analysis: An Entry Point

Conversation analysis (CA) and discourse analysis (DA) are two forms of analysis of language that, nevertheless, focus on quite different aspects. Conversation analysts are interested in the way language (langue) is used in interaction and how this use brings into being social organization and institutions. That is, CA focuses on talk-in-interaction. The fundamental assumption of CA is that "what a doing, such as an utterance, means practically, the action it actually performs, depends on its sequential position" (CA 6).

Conversation analysis: A quick overview [External link, broken, FQS, January 2004]

1. Introduction-Producing Scene

Two researchers (Michael and his alter ego, Ken) in a small hotel room—slightly damaged during an earthquake a few weeks earlier—in Seattle during the 2001 annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association. During the week and between attending a few sessions, Michael has been reading installments 2 and 3 for a review article, Critical Textwork (CT) and Applied Discourse Analysis (ADA), having read Doing Conversation Analysis (DCA) a week earlier during another conference.

|

Ken: |

What have you learned from reading these books? |

|

Michael: |

(Long pause) I am not sure whether I learned from the books, in the sense of "getting something out of them." It is more a matter of developing my existing understanding in front of these books as text. These texts provide occasions in which understanding has unfolded, become articulated, and unveiled. Just look at the sidebars in the "introduction and first-level critique" to each volume. |

|

Ken: |

You emphasize in front of as distinct to from? |

|

Michael: |

Yes, because with RICOEUR I take interpretation to be an articulation of understanding in front of the text rather than a search for meaning in the text or in some reality behind the text. |

|

Ken: |

How are you going to set up your analysis of these three books? |

|

Michael: |

Well, across the three books, the authors are giving me all the cues I need. David NIGHTINGALE (CT, chapter 14) introduces phenomenology and the role of the body, Hakan DURMAZ (CT, chapter 9) proposes to use activity theory as a framework for reading a piece of film, and the dialectic relation between understanding and (hermeneutic, scientific) explanation is articulate by Paul ten HAVE (e.g., DCA, pp.34ff). So I want to use some of the frames I found in a reflexive way and apply them the texts themselves. |

|

Ken: |

These references are only a pretext, for you are using your own theoretical framework, activity theory and the associated subject-centered (phenomenological) analytic method. |

|

Michael: |

Yes, I think that these allow me to articulate my ideas about these books, particularly some of the contradictions between the claims within these texts. Many authors neither articulated the different activities that produced their own texts and the texts that they analyzed nor articulated the relationship that their texts bear to the activity that produced their analyzed texts or to the activities that these texts speak about. |

|

Ken: |

I bet you will write a reflexive piece where content (message) and form of your argument (medium) are consistent with one another? |

|

Michael: |

I make us have a conversation about conversation analysis and discourse analysis. This is then a constructed world, a world set up deliberately and intentionally, in which people have relations that are designed. The author, as you can see from the sidebar, is always made present in the text—constructed as the books I reviewed or the worlds of the people the different texts are about. [1] |

2. Introduction-Producing Scene

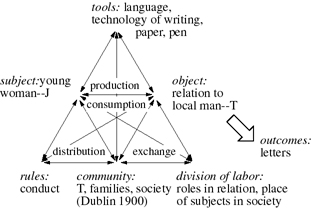

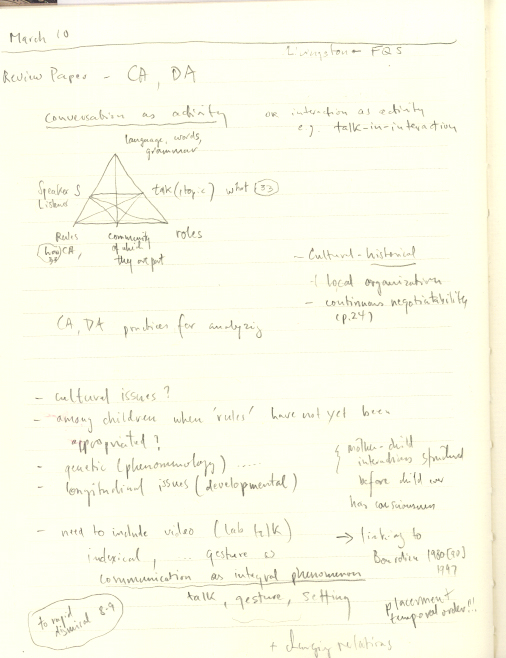

To be able to relate, compare, and distinguish different kinds of activities, I use activity theory (LEONT'EV, 1978), depicted here using ENGESTRÖM's (e.g., 1999) heuristic that focuses on six major dimensions of an activity system and on the way in which the relation between any pair of dimensions is mediated by a third (Figure 1). The six dimensions are the subject (individual or group) of the activity, the activity-motivating object, the tools available as resources in the activity, the narrower and larger community of which the subject is a part, the division of labor in the activity (e.g., roles), and the rules that exist in the community. For example, Figure 1 the activity of courtship around 1900 in Dublin from the perspective of the young woman J (CT, chapter 3), who is therefore the subject. The object of the activity is J's relation to T. However, this relationship between subject and object is not direct but mediated by the tools available to J. For example, language, the technology of writing, and the required instruments (paper, pen, and ink) mediate this relationship. Furthermore, the relationship between the subject and her object are also mediated by the roles that the early 20th century Irish society attributed to a woman and a man in a courtship relation (i.e., division of labor). The relationship between J and T is therefore mediated by the rules of conduct of their time. That is, an activity-theoretic analysis focuses not only on the primary entities but also on all the mediated relations that exist between any two pairs of entities. Most importantly, the entities and activity system are not stable but undergo continuous (historical) change. Activity theory is a cultural-historical form of analysis of activity. [2]

Figure 1: Activity system of courtship from the perspective of a young woman engaged writing letters to a local man, T. [3]

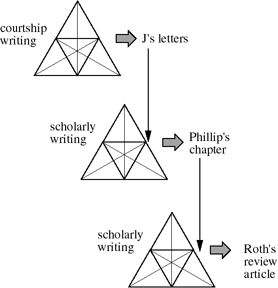

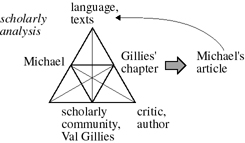

With this basic framework, I can articulate (and analyze) the relations between different activity systems and particularly the relationship between the activity that produces some artifact and the activity system in which these artifacts are anal-yzed. Thus, Figure 2 constitutes my way of depicting the relationship between (a) the activity of writing letters as part of courtship, (b) the activity of analyzing these letters, the objects of a second activity system, and (c) the activity that produces a review article, which takes the chapter as its object. Articulating the different activities in terms of neighboring and related activity systems allows us to ask questions about the relationship within and between activities. [4]

Figure 2: Relationship between a series of neighboring activity systems and the different texts (outcome) produced in each.

[5]

|

Ken: |

So you have found a way of introducing your currently favorite theoretical framework, activity theory, into this review article. But tell me, why this theory rather than any other? |

|

Michael: |

Activity theory appears to me as an appropriate heuristics because it articulates knowing and learning in a systemic way. Thus, from an activity theoretic perspective, I do not expect that a person who changes into another activity system knows and learns in the same way. The individual subject is embedded in a different way. Because the unit of analysis is the activity system, knowing and learning are not attributes of individual subjects but of activity systems. |

|

Ken: |

So you are saying that an individual, like one of the teachers I am coteaching with, is expected to be somehow different during teaching than during an interview situation? |

|

Michael: |

Yes! The difficulties we experience in thinking this through has, in my view, to do with the conflation of two forms of identity, which RICOEUR (1990) calls idem-identity and ipse-identity. The former refers to the identity of the body as a physical entity, which does not change when your teacher moves from the classroom to the interview room. The latter refers to the Self, which is a function of the context made thematic by activity theory. |

|

Ken: |

Let me get this straight. Activity theory can provide an account of the changing experience of Self, for example, of a person who is a loving husband and father in the morning and subsequently becomes a tough businessman who lays-off one thousand workers? |

|

Michael: |

Yes. Furthermore, activity theory acknowledges the historical dimensions of activity systems. |

|

Ken: |

But you have not made the historical dimensions of your own analysis clear! |

|

Michael: |

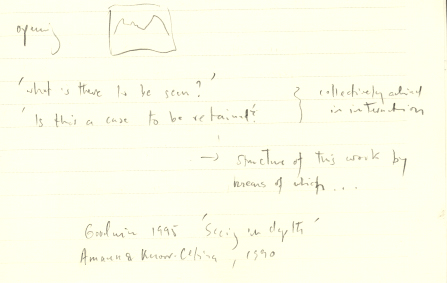

I did write it, but only point you to it at this place. By clicking here, you can see my earliest notes for this article and a brief analysis. But let me give a brief lecture on reflexive phenomenological hermeneutic analysis that I think goes well with the subject-centered (Marxist) critical psychology of Klaus HOLZKAMP (1983) that I use in conjunction with activity theory. [6] |

3. Lecture on Reflexive Phenomenological Hermeneutic Analysis

In the past, knowledge, articulated in the form of scientific language and various mathematical forms has been viewed as a mirror of the world (RORTY, 1979). Scientists of all brands presupposed an isomorphism between a world described and articulated in the form of text and the worlds that we experience as part of being-in-the-world. More recently—in the wake of postmodern scholarship in literary studies and in the wake of empirical studies in scientific laboratories—the isomorphic relationship between texts (discourse, representations) and the world of lived experience (praxis) has not only been questioned but largely been debunked as myth (LYNCH, 1991). This has consequences not only for the relationship between scientific knowledge and the world it articulates but also for the relationship between human activity (praxis, including talk in praxis) and the articulation of this activity (talk about praxis, theory). [7]

Being-in-the-world (praxis) is the ground of understanding; this understanding "testifies to our being as belonging to a being that precedes all objectifying, all opposition between an object and a subject" (RICOEUR, 1991, p.143). Thus, many children and adults formulate well-structured sentences in and discourses of their mother tongue very well but know little (in explicit ways) about semantics or grammar. Understanding formulated in this way precedes all reflection. In interpretive work, this understanding is a prerequisite of the hermeneutic analysis that leads to explanation. That is, understanding envelops explanation, which it precedes, accompanies, and concludes. Explanation, in turn, develops understanding by articulating it and disclosing (structural) relations of its parts. Understanding and explanation are therefore two, dialectically related aspects of hermeneutic analysis. Hermeneutical reflection is reflexive because the constitution of meaning is contemporaneous with the constitution of the self. The analyst comes to understand not something that lies hidden behind a text but something disclosed in front of it. In the case of written text, what is important to understand interpretation is therefore less the author who signs a text (and his/her intentions) and more the reader who cosigns it (DERRIDA, 1988). [8]

|

Ken: |

I begin to feel a little bit like the protagonist in MUSSORGSKY's Pictures at an Exhibition, leading the reader from one tableau to another. But let's attempt to unpack your lecture a little bit, it is pretty dense, "vintage Michael" as one of your reviewers once said. I see your first paragraph as linking the first-person perspective on lived experience to activity theory. |

|

Michael: |

Praxis has its own dynamic (BOURDIEU, 1980), providing the individual subject with a unique perspective. But teaching kids and being interviewed about teaching are quite different forms of praxis, giving rise to different ways in which we experience ourselves. |

|

Ken: |

I understand your focus on praxis as a grounding of knowing in lived experience, the adjective of "phenomenological." |

|

Michael: |

This primary understanding is the mostly unacknowledged basis of all scholarly activity, concerned with explanation, which, in the human and social sciences, requires hermeneutic analysis. |

|

Ken: |

So we have two adjectives, what about the third one, reflexive? Does it have to do with the notions of "critical doubt" (BOURDIEU, 1992), "suspicion of ideology" (MARKARD, 1984), and "hermeneutics of suspicion" (RICOEUR, 1981) that we have been bantering with in our own work? |

|

Michael: |

I see analysis as reflexive in two ways. First, because understanding and explanation form a dialectic unit, they are in a reflexive relation. Second, an analysis is reflexive when it takes itself as object. That is, understanding and explanation are not "applied" to objects external to themselves but to their own dialectical relation. |

|

Ken: |

Your final point pertains to the relationship of author, text, and reader. |

|

Michael: |

We used to think that reading allows us to recover the author's meanings or intentions, something behind the text, or meaning in the text. My own research on scientists' interpretation of unfamiliar graphs made me realize that they were not discovering information someone else "deposited" in the graphs but they were articulating and developing their own understanding of the world (e.g., ROTH & BOWEN, 2001). That is, the graphs (a form of text) presented occasions, work sites, for the scientists to articulate something that can be found neither in the graphs nor in the author's intentions. |

|

Ken: |

OK, I understand. So you take this as an analogy for your own reading of the three books. And you articulate this analogy in the bubble at the beginning of this text and in the sidebars of the more traditional reviews. [9] |

"Conversation with the author" or "meet the author" are the signifiers for a venue used by bookstores and publisher-exhibitors during conferences, like the one I attended while working on this article, to advertise, interest potential readers, and bring the author to the readership. [10]

4.1 Talking about "talking about praxis"

Val GILLIES (ADA) and Paul ten HAVE (DCA) meet Michael, the author of this text, Pierre BOURDIEU, and Paul RICOEUR.

|

Val: |

My study is based on a series of semi-structured interviews conducted in the respondents' own homes. The aim of my analysis was to understand the ways in which respondents construct the activity of cigarette smoking. I achieved this by identifying the discursive meanings attached to smoking behavior and identifying the discourses that informed the accounts of cigarette smoking ... I argue that the discourses and discursive constructions that have been explored in my analysis shape how these women behave and experience the world. (GILLIES, ADA, p.69, 80) |

|

Michael: |

But aren't you conflating what people say about smoking in your interview situation with their smoking in everyday life? Aren't these two very different activities, with different motivations? |

|

Paul: |

This is why, in CA tradition, I attempt to explicate the inherent theories-in-use of members' practices as lived orders, rather than trying to order the world externally by applying a set of traditionally available concepts, or invented variations thereof. (Paul ten HAVE, CA, p.32) |

|

Pierre: |

The most insidious trap resides, without doubt, in the fact that agents take recourse voluntarily in the ambiguous language of the rule, of grammar, of moral or of law, to explicate a social practice that follows very different principles. (BOURDIEU, 1980, p.174) |

|

Paul: |

So the verbal accounts participants might produce regarding their own conduct are rejected also, at least as primary data on the interactions accounted for. This is because participants may not know afterwards what they have been doing and furthermore tend to justify their behaviors in order to account for what they deem to be community-specific rational ways. (Paul ten HAVE, DCA, p.33) |

|

Michael: |

What Val GILLIES and other discourse analysts in ADA and CT do is take the outcomes of a secondary activity system, the interview, as a prima-facie evidence for the (subjective) experience in a primary activity system. |

|

Ken: |

You know that I am not yet familiar enough with activity theory to use it as a framework to analyze some situation. How would you articulate the problems you identified in terms of activity theory? |

|

Michael: |

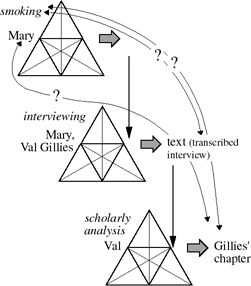

Take, for example, the chapter by Val GILLIES on smoking. I view Mary's smoking as the primary activity, Mary and Val as the subjects in the interview activity, and Val as the subject involved in scholarly analysis and writing. Let me sketch the three activity systems. (Figure 3) |

|

Ken: |

Val, as I understand it, takes the interviews as reflecting the motivation underlying Mary's smoking. |

|

Michael: |

This direct relation is but one of the problems. At the next level, Val makes the claim that the discourses and discursive constructions that she explored in her analysis shape how these women behave and experience the world. That is, she links the outcomes of her own activity directly to the activity of smoking by someone in a different activity system. |

|

Ken: |

Do I hear you critique the absence of mediation? |

|

Michael: |

Well, wouldn't you assume that the activity of interviewing someone about smoking shapes what is being said about smoking? I see the interview as a situation where people do "interview talk about smoking." Having been a smoker in my distant past, talking about smoking is very different from lighting up while you are taking a coffee with colleagues in the staff room. [11] |

Figure 3: Smoking and scholarly analysis of an interview about smoking are two neighboring activity systems, the second taking

the outcome of the first as its object. [12]

|

Ken: |

So you have articulated a reason for two of the three question marks in Figure 3. Do you want to say that there is also a tenuous relationship between Val's chapter and Mary's identity, including the identity as a smoker? |

|

Michael: |

I see what RICOEUR (1990) calls ipse-identity, the Self as distinct from the material body, which is idem-identity, realized in the relationships of all entities and mediated relations that make a person's lifeworld. These two aspects of identity stand in a dialectical relation, each having the other as a prerequisite, but also being very different thereby leading to tensions. What Val does not address is the relation between her text and smoking as an aspect of Mary's lived experience in her world. |

|

Ken: |

So there is an under-theorized distance between GILLIES' chapter and the phenomenon that she writes about? |

|

Michael: |

Not only GILLIES' chapters, but the chapters of ADA and CT more generally. Furthermore, I can't even reproduce the connection between some of the data authors provide and their own texts. For example, Barbara DELAFIELD presents an excerpt from a classroom interaction, which she subsequently analyzes. I juxtapose these two pieces of text: [13] |

|

|

Sequence 3: This could be the story Jill: Where wherever the girl found the button she could have took it home and looked after it and maybe her mum gave her the money to go and buy the teddy bear and er took it home and could have found the button again wherever it was and sew it back on and sew it on the teddy. T: It could possibly have happened go on Simon what did you want to say to that. When Jill, sequence 3, attempts to enter the discussion using a 'story telling' discourse, the teacher's response, 'it could possibly have happened', is more dismissive, neither offering promise of later discussion, as in 2, nor acknowledging its use to the group, as in 4. ... children's attempts to enter the discussion were repressed ... The offering at 3, however, a 'story telling' discourse, would not be seen as appropriate to this process, and can therefore be dismissed without encouragement. DELAFIELD, CT, p.56, 58 [14] |

|

Ken: |

Would you suggest that DELAFIELD should have used CA, as Paul ten HAVE describes it, to bring out what, if anything was dismissive in the interaction? |

|

Michael: |

Yes, I think that it is an aspect of reflexive phenomenological hermeneutic analysis to question one's concepts ... BOURDIEU (1992) writes that the pre-constructed resides everywhere. Showing how social structure emerges from talk-in-interaction is a bottom up approach to social analysis. Rather than accepting "power" and "dismissive attitude" as a priori (explanatory) concepts, the conversation analyst has to articulate these as achievements of interaction. |

|

Ken: |

By this argument, your analysis begins to turn on yourself, because you have not theorized the relationship between your own analysis and the texts in ADA and CT. |

|

Michael: |

I am doing this in the following diagram, which I had already prepared to be able to deal with this criticism. (Figure 4) My own text becomes an elaboration of that by Val GILLIES and the other contributors to ADA and CT. |

|

Ken: |

The that your text returns to the tools is probably an indication that the text returns as a resource into the community? |

|

Michael: |

Yes. It can potentially move further and bring about changes in other entities of the activity system (e.g., ENGESTRÖM, 1996). The under-theorized nature of the text also comes out in the difference between citing another author and citing a research participant. The former is treated as being aligned with the author. But using texts from interview transcripts is treated as "giving voice to" research participant—for example, in the CT chapter by David RUDD. [15] |

Figure 4: In the scholarly community, both Val GILLIES' chapter and Michael's review article constitute texts in the "archive" (DERRIDA, 1995), the latter augmenting the former. [16]

|

Michael: |

The authors in ADA, and particularly in CT do not distinguish between texts—everything is text including film, 19th-century garden plans (For a different look and analysis at gardens click here), television, and bodies ... So I see problems in going from the world of lived experience to text and returning from text to the lived world. In this way, it makes sense that discursive constructions can be said to have repercussions and effects in the everyday world of experience. |

|

Val: |

I suggested that these discursive constructions work to constrain as well as facilitate certain behaviors and actions, and as such the use of discourse is seen not only as accounting for cigarette smoking but as actively maintaining this behavior in the future. (GILLIES, APA, p.68) |

|

Michael: |

I tend to disagree, for the relation between text and lived experience is rendered unproblematic. I think Paul does a nice job in articulating the difference between living speech and written text ... |

|

Paul: |

In living speech, the ideal sense of what is said turns toward the real reference, toward that "about which" we speak. At the limit, this real reference tends to merge with an ostensive designation where speech rejoins the gesture of pointing. Sense fades into reference and the latter into the act of showing. (RICOEUR, 1991, p.108) |

|

Michael: |

But writing changes everything. |

|

Paul: |

Such is the upheaval that affects discourse itself, when the movement of reference toward the act of showing is intercepted by the text. Words cease to efface themselves in front of things; written words become words for themselves. (RICOEUR, 1991, p.109) |

|

Ken: |

I think it is time for you to move on and deal with the problematic notion of meaning, or perhaps, the problematic ways in which "meaning" is used in the two books on discourse analysis. [17] |

|

Michael: |

Meaning is a very problematic concept, and throughout the two books on discourse analysis. In a way, there are different meanings to "meaning," or, as WITTGENSTEIN (1958/94) would have said, different ways in which the term is deployed in the ongoing language game. One problem with the notion of meaning in the ADA and CT chapters is that the analyses are not appropriately situated in the historically contingent nature of the hermeneutic activity. The authors generally do not sufficiently (or at all) acknowledge that the interpretive horizon of the "reader" very much is one moment in the dialectical text-reader unit. |

|

Ken: |

Why don't you let the authors duke it out with some of your role models? |

Tom PHILLIPS (CT) and Ian PARKER (CT) meet Jacques DERRIDA, Paul RICOEUR, Eric LIVINGSTON, and Michael, the author of this text.

|

Tom: |

I think I can recover the meaning intended by the writer of the letters that I analyze. To approach these letters, I suggest that they be read rather than analyzed, where the meanings, communications and pragmatics are sought in ways similar to how the writer intended. (PHILLIPS, CT, p.30) |

|

Michael: |

I disagree that you can read these letters in the way the author intended for two reasons. First, Jacques (DERRIDA, 1988) told us quite clearly that a text never articulates the author's intention; rather, the reader always cosigns the text. Second, texts can never be read in their original ways. MERLEAU-PONTY (1945) used a diagram first introduced by HUSSERL to show how the reading of an text changes as we move away from its moment of production ... |

|

Jacques: |

... because the first impression is scriptural or typographic: that of an inscription which leaves a mark at the surface or in the thickness of a substrate. (DERRIDA, 1995, p.26) |

|

Michael: |

So when you talk about first impression, you already indicate something that comes thereafter. It is something like the original, the archived text. Interpretation augments the archive and creates new relations between texts. |

|

Jacques: |

By incorporating the knowledge deployed in reference to it, the archive augments itself, engrosses itself, it gains in auctoritas. But in the same stroke it loses the absolute and meta-textual authority it might claim to have. One will never be able to objectivize it with no remainder. (DERRIDA, 1995, p.68) |

|

Michael: |

When you say that the archive engrosses itself, you really imply that semiosis is unlimited in the way ECO (1984) wrote it? |

|

Jacques: |

Yes, the archivist produces more archive, and that is why the archive is never closed. It opens out to the future. (DERRIDA, 1995, p.68) |

|

Ken: |

Jacques is telling you that your own text, the one that you have made me part of, is but one possible reading of the three books, themselves being some sort of first impression, an archive, which you augment. This is the meaning of the arrow that takes your, this article back into the activity system of academic scholarship (Figure 4). |

|

Michael: |

If we push this a little further, my reading of this archive (CT, ADA, CA) does not reveal some transcendent meaning but constitutes a project of understanding that involves me as much as it involves the text. |

|

Ken: |

But, as your friend Eric pointed out, your reading also reveals something about our culture, it is a cultural practice revealed in your reading—and this text that you are in the process of writing. |

|

Michael: |

When you said 'friend', I thought you meant to refer to Malcolm ASHMORE (1989), the author of The Reflexive Thesis, who has allowed me to learn a lot about reflexivity and whom I have impersonated a number of times in the past. But let me get back into this other world. |

|

Ian: |

I think I did say that we are not in control of texts. One of the important implications of structuralist and post-structuralist accounts of language is that we are not entirely in control of meaning. Words and phrases have meanings that are organized into systems and institutions, what Foucault called 'discursive practices' that position us in relations of power. (PARKER, CT, p.6) |

|

Michael: |

But we are never in control of what we say or write. In the utterance we speak or the sentence we write there is a dialectic tension: it is both ours and not ours. Or, as BAKHTIN (1981) said, we use language, which is not ours, for our own intentions. "Words," he said, "do not exist inside or outside of individual consciousness; language lies 'on the borderline between oneself and the other' and 'word in language is half someone else's'" (p.293). There is then also a dialectic tension between the relations of author-text and reader-text. |

|

Jacques: |

I am monolingual. My monolingualism dwells, and I call it my dwelling it feels like one to me, and I remain in it and inhabit it. It inhabits me. The monolingualism in which I draw my very breath is, for me, my element ... Yet it will never be mine, this language, the only one I am thus destined to speak, as long as speech is possible for me in life and in death; you see, never will this language be mine. (DERRIDA, 1998, p.1,2) |

|

Ken: |

Michael, you would not have made Ian, Jacques, and yourself say this in this text if it did not have implications for the ways text is interpreted? You probably used this as a set up to make some statements about the way in which CT and ADA construct their worlds. You are making a strong argument against the assumption that an external reading of interviews (text) can get the researcher (reader of the text) into the lifeworlds of the person interviewed. |

|

Michael: |

Sorry, Ian, my alter ego began to speak up. Say in the book you edited, the authors seem to assume that meaning is somehow hidden in the text, that there is a sense of a text directly related to issues of power. |

|

Ian: |

Yes, here we are concerned with issues of power, and we also want to open up a place for agency, as people struggle to make sense of texts. This is where people push at the limits of what is socially constructed and actively construct something different. (PARKER, CT, p.7) |

|

Michael: |

But Eric and Paul see the issues differently. |

|

Paul: |

Because what we want to understand is not something hidden behind the text, but something disclosed in front of it. (RICOEUR, 1991, p.165) |

|

Eric: |

I think that this "something" is reading. Reading is neither in a text nor in a reader. It consists of social phenomena, known through its achievements which lie between the text and the reader's eye, in the reader's implementation of society's ways of reading, in reading what the text says. (LIVINGSTON, 1995, p.16) |

|

Paul: |

So to understand a text is to follow its movement from sense to reference, from what it says to what it talks about ... |

|

Eric: |

The work of reading is therefore the work of finding the organization of that work a text describes. (LIVINGSTON, 1995, p.14) |

|

Michael: |

So in contrast to Ian and the other authors of CT and ADA, you articulate a phenomenology of reading, a practice. They take texts as objects that have meaning and sense, and therefore power, embedded. |

|

Eric: |

As I understand it, reading leaps beyond its textual basis to the thing that is transparently read, and in that leap, in the anonymity of the organized course of reading that is now available, the social character of the phenomenon lies. (LIVINGSTON, 1995, p.16) |

|

Michael: |

So language is as much a part of the situation as the material world that embeds us and on which we depend? |

|

Ken: |

Michael, I think it is important that you address a fundamental issue that has been latent in these first two conversations but that has to be addressed head on: the body, or really the absence of the body. [18] |

4.3 The absence of the body in writing

|

Michael: |

"Thanks for seguing into the new topic," you would say if you were present in body and flesh. As I was reading CT and ADA, my greatest worry concerned the absence of the body. The contributors to the two texts, exemplified by Ian PARKER and Val GILLIES in the following panel, drive discourse between people and their embodied experiences. There were texts used by the authors to make inferences about life and lived experiences. In the books on discourse analysis, the people who figure in the texts always appear to be at a remove from themselves, at least one level away from being in the world. [19] |

|

|

The book illustrates ways in which discourse may be studied wherever there is meaning, and so it also includes an accessible introduction to the principles of discourse research across many types of texts. (PARKER, CT, p.1) I analyze the multiple meanings and significance working-class women attach to the practice of cigarette smoking. (GILLIES, ADA, p.69) [20] |

|

David: |

I disagree. In fact I did bring the body back into the text: As a dissected frog refuses to jump and a butterfly collection no longer flits around a warm summer garden, so the body as object, image or text (in and of itself) is no more capable of explaining the lived experience of the human body than a corpse in the library with a lead pipe beside its head. (NIGHTINGALE, CT, p.170) |

|

Michael: |

This, however, does not overcome the distance language produces. Biography and experience, testimony ("Zeugnis") and presentation, can never be represented and later recovered in any form of re-presentation. (MÜLLER, 1972) (For an articulation of the problem, click here to go to my gardening example.) |

|

Paul: |

In living speech, the instance of discourse has the character of a fleeting event. The event appears and disappears. This is why there is a problem of fixation, of inscription. What we want to fix is what disappears ... If it is not the speech event, it is speech itself insofar as it is said. (RICOEUR, 1991, p.146) |

|

Michael: |

So the body plays an important role in who we are, how we understand ourselves, and ... |

|

Pierre: |

In a HEIDEGGERian word play, one could say that disposition is exposition. Because the body is exposed (to different degrees)—put into play, into danger in the world, faced with the risk of emotion, hurt, and sufferance, sometimes even death, therefore obliged to take the world serious—it can acquire dispositions that themselves are openings onto the world, that is, to the structures themselves of the social world of which they are embodied form. (BOURDIEU, 1997, p.168) |

|

Michael: |

The problem with Ian and Val's statements is that in much of our life, we do not attach meanings. I used to smoke. But I cannot remember having attached meaning to smoking. I just smoked. I began because my partner at the time did so. I was in my 20s and had no need to show off. Perhaps I felt like smoking without feeling this feeling in any conscious way. It is similar to the way I garden. There is no meaning to the gardening other than I garden. I garden because I garden because I garden ... I do not attach meaning. Being-in-the-world, praxis, is the ground of understanding without intervening discourse. |

|

Paul: |

I agree. This understanding testifies to our being as belonging to a being that precedes all objectifying, all opposition between an object and a subject. (RICOEUR, 1991, p.143) |

|

Michael: |

So everyday understanding is not a reflexive "understanding" but more an absorbed coping. We do not live our lives distanced from ourselves. We do not construct or attach meanings but life is immediately imbued with sense from the very beginning? We are our bodies and our lifeworlds. |

|

Ken: |

Can you provide us with an example of the distance that you are talking about? |

|

Michael: |

I don't really want to interrupt the conversation that I am having with Paul and Pierre, but you can click here for the sketch of such an analysis. |

|

Ken: |

(Coming back from the link) I see, you wrote an analysis of an analysis, where your analysis turns the earlier analysis against itself. |

|

Michael: |

Sorry Pierre, I got interrupted by my alter ego. I was saying that we are our bodies and lifeworlds. |

|

Pierre: |

And I wanted to say that this is because world encompasses me (me comprend) but I comprehend it (je le comprends) precisely because it comprises me. It is because the world has produced me, because it has produced the categories of thought that I apply to it that it appears to me as self-evident. Habitus is what you have to posit to account for the fact that, without being rational, social agents are reasonable ... (BOURDIEU, 1992, pp.128, 129) |

|

Michael: |

The problem that I have, then, is that ADA and CT insert discourse between people, their bodies, and their experience. If we experience the world prima facie, then we have lived experiences that are not mediated by discourse. There are many things I do without discursively articulating it. Listening to Arvo PÄRT's Kanon Pokajanen soothes me; but I realize its soothing nature only when I reflect upon it not when I am absorbed in listening. I appreciate the view of islands and mountains from my kitchen window; but I realize "appreciation" only when I allow discourse to enter absorbed viewing. Through my hands, I "know" the right amount of liquid and flower in the dough; but I become aware of this as "knowing" only when I am trying to explain to others my experience of baking and preparing the dough. Through the body, I experience a rush while riding my road bike through the hills, but I become aware of this as rush while I am writing these words. |

|

Ken: |

I see you have come to an area that has been a focus of your research for quite some time—the embodied and distributed nature of knowing. |

|

Michael: |

Well, yes. In fact, the embodied nature of knowing is also the topic of a book that I would like to start sometime soon during my upcoming sabbatical. |

|

Ken: |

I wonder how you will finish this review article. Do you have any definitive conclusions? |

|

Michael: |

Well, in the more traditional review texts, I said something about whether or not I would use these texts in my own classes. You can get to these conclusions directly by following these links: ADA-Conclusion, CT-Conclusion, or DCA-Conclusion. |

|

Ken: |

(Coming back from the link) Yes, but what how are you going to end this text? |

|

Michael: |

By writing, "THE END." [21] |

Supplement I: Ian Parker and the Bolton Discourse Network (1999). Critical Textwork

1.

This book, introduced by Ian PARKER, brings together 16 chapters grouped into four parts identified by the nature of texts analyzed: Spoken and written texts (interviews, letters, fiction, and lessons); visual texts (comics, advertising, television, and film); physical texts (cities, organizations, gardens, and sign language); and subjectivity in research (bodies, ethnography, silence, and action). Each of the rather brief chapters (10-15 pages) can be said to have followed a very strict format of introduction/exposé, discussion of the text ("Text"), a plate with the text to be analyzed, an analysis ("reading"), as well as "disadvantages" and "advantages" of the approach. [1]

2.

The authors begin their chapters with an untitled section, where they present a brief and far from comprehensive review of the methodological literature on their chosen topic (meaning in groups, romance, absence of children's view on literature, etc.) and methodology of research and analysis (discourse analysis, phenomenology, activity theory, etc.). Subsequently, the authors use a framed text box to present their data, and a description of this data in a section titled "text." They analyze their data in the sections "reading," and then describe, in the final two sections, the shortcomings and strengths of the chosen theory or method. Soon after beginning the book, the line "resté sur ma faim" (left hanging) surged and occupied me, as if asserting itself, the French much better expressing the difference between the great anticipation ("hunger") with which I had started this book and what I experienced while reading it. The shortness of the chapters and the rigidity of the representation left underdeveloped many of the ideas that I thought needed to be addressed, particularly at this point in the history of discourse analysis, that is, more than a decade after Opening Pandora's Box (GILBERT & MULKAY, 1984) or the ground-breaking work Discourse and Social Psychology (POTTER & WETHERELL, 1987), or Discursive Psychology (EDWARDS & POTTER, 1992) all of which I had tremendously enjoyed and used in the past. [2]

The rigid format generates interesting tensions, for it forces authors to present in textual form what might otherwise be difficult to represent in textual form. In other words, being forced to present their data in textual form, the authors are forced to generate data that turn everything into text—bodies, lived experience, film, or silence. It might have served the authors and editor well to make a crucial distinction between data and data sources. Data sources may take all sorts of form, for example, the audio recording of an interview or a telephone call, the lived (unreduced) experience of walking through a 19th-century Victorian garden, or the visits to a historical site and Granada Studios in Manchester. From these data sources, the author constructs the data that are subsequently analyzed. The contributors to Critical Textwork (CT) would have definitely benefited from an explicit discussion of the transformations involved in going from the phenomenological dimension of an event to the ultimately published chapter. (Pertaining to conversation analysis, ASHMORE and REED [2000] have conducted such an analysis.) [3]

That is, the authors do not explicitly discuss that what the reader gets to see as data has already gone through at least one level of filters and analysis. This is an important step to make salient, for the reader can no longer reproduce the same analysis that was done by the author. As my own research among high school physics students showed, just what the observer sees when looking at a demonstration may differ among spectators (ROTH, MCROBBIE, LUCAS, & BOUTONNÉ, 1997). Thus, what the students described as having occurred after watching a teacher, sitting on a rotating stool and spinning a bicycle wheel differed—some said that the teacher moved; others suggested that he didn't move. Based on these observations, they subsequently used a variety of theoretical models to explain why the teacher should have (not) moved. Because their data were different, it is not surprising that they used different theoretical frameworks in order to produce consistent readings. [4]

Thus, when the chapters move to different forms of "text," such as bodies, cities, films, television, or gardens (see my version of it in the insert), the number of problems increases. There is a curious absence in the text of the things being talked about. This absence begins with PEARCE's chapter concerned with advertising, but the data of which it is a description of a poster rather than a copy or an iconic depiction of the poster. Throughout reading his analysis, I wanted to see the poster in order to check the primary reading, which had produced descriptions such as "unusually thin," "she looks somewhat expressionless at the audience," or "seemingly untidy but paradoxically regular." (In several cases, the "data" actually contain analytic commentaries [e.g., CT, p. 83, 120].) While reading, I annotated (in the margins) RUSSELL's analysis also with the comment "same problem as before ... lack of opportunity for the reader to disagree with the analysis." I thought readers might enjoy a discussion of the difference, differance, differal, of (phenomenologically) analyzing primary, lived experience and analyzing secondary, tertiary, or, for that matter nth-order texts. [5]

3.

Even if I was to overlook these aspects of the book, there were many other ways in which I was disappointed. One of the important disappointments resided in the frequently problematic relationship between the "data" and the "reading" that the authors provided. Repeatedly, I could find no evidence for a particular reading, for the required data had not been presented. There was therefore the tension that the authors presented four pieces of transcripts (BEVAN & BEVAN) or two letters (PHILLIPS) but in their analysis really required much more from their data to support the claims actually made. For example, PHILLIPS conducts a reading of Letter 1 in which the writer makes reference to a person named Lizzie. He then suggests that "Lizzie's inclusion is always significant, as she is perceived as a rival" (CT, p.33). Thus PHILLIPS reads not just this letter but interprets it in terms of his reading of all of the other letters. Here, the notion of intertextuality of a particular text in the body of texts analyzed, the intertextuality of the texts analyzed to other parts of the author's text (e.g., LEMKE, 1992) is insufficiently theorized. I would have thought that a reading of JOYCE's Ulysses or Dubliners might have given rise to tremendous insights about reading and discourse analyzing letters. [7]

4.

In part, the problems are created because the authors voluntarily write themselves out of the narrative. Their agency becomes a mediated agency, or the agency is attributed to an abstract analysis ("[the reading] has tried to show" [CT, p. 76) or chapter ("This chapter is concerned with" [CT, p. 129] or "this chapter had argued" [CT, p. 150]) and section ("The above section raises questions" [CT, p. 209]). This then leads to disembodied readings that anyone could or perhaps should be experiencing. The readings become normative without revealing the community that adheres to this norm, leading to transcendent meanings available to readers in general. Throughout my reading of this book, I became and remained uncomfortable with the apparent assumption that the texts rallied as data would lead to a particular, the author's favorite reading. [8]

Of course, the problems I perceived are not problems in some absolute sense but are related to my own developmental trajectory, having enacted discourse (and conversation) analytic studies of my own whenever the topic of my interest lend itself or required such a form of analysis (e.g., ROTH, 1993; ROTH & ALEXANDER, 1997). The problems exist in reference to my interpretative horizon, a contingent moment of a continuously changing and evolving scholarly Self to which I indexically and self-referentially refer to as "I." I did not come as a novice who felt the need to read an introductory text for students of discourse across the social sciences. Whether I would have been disappointed had Critical Textwork been the first book on discourse analysis is a mote question. Overall, I finished the book feeling that it did not hold what I felt it had promised me; or rather, there was a gap between the actual reading experience and the one I had expected. The one lesson I thought it might teach newcomers to discourse analysis is that "discourse" pertains to situations more broadly rather than text. On the other hand, because of the format of presenting "data" in largely textual form, a naïve reading might come to the conclusion that "everything is text." [9]

5.

I was wondering how I could best encapsulate my feeling about this book. Given that it was announced as an introduction for newcomers to discourse analysis, I thought that an appropriate evaluation would be whether I would consider using the book as a central or peripheral resources. Would I recommend these books to the students in my Interpretive Inquiry courses, that is, the ones I just finished teaching and, more importantly, the other one that I will be starting within weeks from writing these lines? Whereas I could ponder this question in the abstract, this pondering would not bring me closer to resolving a practical question. Not being a person of lengthy (disabling) considerations, I decided not to use these chapters as resource materials because the tight theory-data-interpretation integration that I wish to get my students to attend to is absent from most of the chapters in this book. In my reading, the chapters were in many respects somewhat naive in the way I might expect it from relative newcomers in the research community. [10]

Supplement II: Carla Willig (Ed.) (1999). Applied Discourse Analysis

1.

In this book, Applied Discourse Analysis (ADA), the editor assembled six chapters, in which the authors use discourse analysis to articulate critiques of contemporary social practices. These practices are related to the use of reproductive technologies, articulation of stress in the self-help literature, interviewing of suspects by police officers, sex education, cigarette smoking, and clinical diagnoses of schizophrenia. [1]

WILLIG provides an overview of discourse analysis and a critical review of issues surrounding the adjective "applied" in applied psychology, particularly the problems with the notion of "application," which, in science and technology, was used to distinguish (highly-regarded) knowledge producers from (lowly) technologists and technicians. WILLIG then proposes three ways in which discourse analysis may be applied in everyday settings—as social critique, as empowerment, and as guide to reform. In the six chapters that follow, each author provides an exemplary analysis of books, transcribed interviews (person-to-person, group setting), or transcribed interactions (police-suspects, doctor-patient). [2]

In Stress as regimen: critical readings of self-help literature, BROWN provides another cut at 22 self-help texts that have formed the basis of other articles and of his doctoral dissertation. He suggests that there are five major narrative themes that link everyday life situations and stress: a generic twentieth-century disease, primitive response syndrome, fast pace of modern life, seeing things differently, and juggling work and home. BROWN then describe four devices (metaphors, tropes and rhetorical devices) that the 22 authors rally to assist their readers in building an understanding their relationship to their bodies: heat, war, engineering and computation, and serviceable self. As far as application is concerned, BROWN proposes that his reading, that is, his critique of the self-help literature may help others in understanding the rhetoric applied. Furthermore, BROWN suggests that his categories be applied to other settings such as texts used in strategy documents or marketing reports. [3]

In 'It's your opportunity to be truthful': disbelief, mundane reasoning and the investigation of crime, AUBURN, LEA, and DRAKE provide an analysis of police interrogations, which have as their effect the production of a preferred version of the events on the part of the suspect. For someone who had never been interrogated as a suspect in a crime, this is a highly interesting piece that elucidates the question why there are continuously cases reported in the media about innocent people ending up serving for a crime they never committed. In an exemplary fashion, the authors show how disbelief—on the part of the police officers—is discursively organized, involving the phases of signaling disbelief, warranting disbelief, and reformulating the invitation to the suspect to tell the (officers') preferred version of the events. AUBURN, LEA, and DRAKE then elaborate on a variety of methods used by officers to articulate warrants for their disbelief. These include information culled from witnesses and other indisputable sources of evidence or are based on normative expectations. As the previous chapter, the authors have not actually worked with participants (police or suspects) in order to engage in the praxis of discourse analysis for bringing about change. Rather, in a way typical for academics, the use of discourse analysis as a method for emancipation and policy is being suggested rather than enacted. The need to argue for potential applications leads to somewhat farfetched proposals: "findings from this research could be taken up and developed in conjunction with a whole range of groups who are regularly in conflict with the criminal justice system and for whom a police interview is one of the many steps in their social and political regulation" (ADA, p. 62). The proposed relation between theory/research and practice is a reproduction of the ivory-tower/lowlands divide that has characterized traditional university-community relationships. [4]

In An analysis of the discursive positions of women smokers: implications for practical interventions, GILLIES provides an analysis of interviews with women smokers. In her analysis, she provides a number of dimension of the discursive construction of smoking, including the discourses of addiction, control and self-regulation, and the acceptability and medicinalization of smoking. GILLIES suggests that her analysis "may promote greater understanding of why individuals engage in a behaviour which is so obviously detrimental to health" (ADA, p. 80). In my reading, there are a number of problems with GILLIES' work. First, GILLIES assumes, somewhat tenuously, that the "discursive meanings attached to smoking" drive actual smoking behavior. Thus, and this is my second point, she assumes that by assisting female smokers in changing their discourse, they would also change their behavior—decreasing or abandoning smoking. I find such assumptions idealistic and highly problematic given what we, as a research community, know about the relationship between action and descriptions of action. For example, JORDAN (1989), who had conducted an ethnography among Mayan midwives, provided an analysis of the effects of an UNESCO course on the day-to-day practices of midwifery in native communities. JORDAN suggested that what the midwives learned was to use Western medical discourse whenever they talked to Western doctors and nurses (such as in the workshop and it follow-up) but very little or nothing changed in the everyday practices of midwifery back in their community. Thus, a change in discursive practice, enacted in a Western medical context, actually changed very little in the practices that are situated in the villages and cultures of the people. At a more abstract level, BOURDIEU (1980) provided a detailed analysis of the relationship between practice (here smoking) and talk about a practice (here provided in interview). The problem with GILLIES' analysis therefore lies in the unthematized tension between what people say in the interview situations, explicitly set up to talk about smoking with an interviewer who clearly has anti-smoking dispositions, and the everyday experience of lighting up in a variety of situations. I do not think that we can come to an understanding of smoking if we do not seek and provide a phenomenological analysis of the phenomenon, an analysis that has to be necessarily contextual. That is, context glares in its absence—yet there are almost daily media reports indicating that the real problem of "drug addicts" is the context into which they return rather than getting off the drug. [5]

To produce the chapter entitled Deconstructing and reconstructing: producing a reading on "human reproductive technologies", PUJOL had set up group interviews, which he constructs as a "form of interaction close to everyday conversation" that minimizes the interviewer role. (Of course, bringing people together in order to talk about reproductive technologies already sets up a special kind of context, one in which participants are expected and orient themselves to doing "human reproductive technology" talk.) Assuming that heterogeneous groups lead to stereotyped answers, PUJOL organized the participants according to the amount of information about (limited, some), experience with (in successful/unsuccessful treatment, as donor or through donor contact, as medical professional), or position toward the topic (religious, feminist) that they had prior to the interviews. Although the author explicitly acknowledges that interpretation is not about uncovering something that is behind a text but about constructing it through the interaction between reader and text (see the background sidebar, in which reader and text meet face to face), I do not find the reflexive moment that signals the author's own work as a construction. The definite statements that constitute his reading seem to stand in contrast to the multiple ways in which texts can be read that are implied in the reader-text interactions. (Of course, it may be my own monolingualism, "the monolingualism of the other" [DERRIDA, 1998], that ear of mine which is "the ear of the other that signs" [DERRIDA, 1985].) Furthermore, the author produced a traditional narrative, embedding participant quotes into the dominant text that constructs its object, "reproductive technologies." Contrary to other contributors, PUJOL does not even attempt to show how discourse analysis could potentially be used as a tool in his context, used by his participants, to grabble with the salient issues and thereby, hopefully, begin to empower and emancipate themselves. [6]

WILLIG draws on interview transcripts with 16 heterosexual men and women to construct her chapter entitled Discourse analysis and sex education, in which she presents an analysis of sexual risk taking in terms of marital discourse, discourse of trust and sexual activity. These interviews had been data sources for a series of articles, of which the present chapter is an extension. While this chapter is interesting in its own right, as a statement about how interviews about sexual activity can be read, I find WILLIG's chapter falling short in two related dimensions: potential applications and the relation of discourse and practice. As other authors in Applied Discourse Analysis and Critical Textwork, she presupposes that discursive constructions (made in interview settings) have implications for sexual practice, by allowing subjects to position themselves in different ways. She argues that because discourse constructs its object, subjects can change what they currently do sexually. The problematic issue, perhaps, arises from talking discourse as the domain of the individual rather than being something that is enacted collectively. Of course, analyzing interviews independent from the context that they provide, including the interviewer and her active participation in making this a "talk about sexual activity," necessarily abstracts what is being said. In this way, discourse and discursive constructions are reattributed—in classical psychological manner—to the individual rather than to individual-in-setting, as a critical, Marxist psychologist would attempt to do (e.g., HOLZKAMP, 1984). Although WILLIG is critical of her own recommendations, such as educators' use of power to reshape individual subjectivity (by changing discourses), she makes these recommendations nevertheless. Rather than allowing everyday folk to appropriate and shape discourse analysis for their own intentions, whatever the outcome, WILLIG has very specific intentions that she wants others to appropriate in unattenuated ways. [7]

In the sixth study, Tablet talk and depot discourse: discourse analysis and psychiatric medication, HARPER draws on interviews with 9 users of psychiatric services and 12 psychiatric services professionals to provide a rather brief analysis of the rhetorical strategies accounting for apparent drug failure. HARPER suggests that talk about drug treatment failure shares a number of rhetorical features and effects, which need to be challenged in a variety of contexts. He then constructs potential implications for a variety of interest groups, including users of and workers in mental health services, people associated with users, health professionals, academic researchers, and political activists. The model is one of transfer of knowledge and skill from those who know, here practitioners of discourse analysis, to those who do not know, that is, the members of interest groups. Rather than being an example of applied discourse analysis, this chapter provides us with an academic reading of interview material, specifically set up to produce drug treatment talk, and then suggests that others should model themselves and their work on the (deconstructive) methods and their results presented. [8]

In her concluding chapter, WILLIG writes about the opportunities and limitations of applied discourse analysis. From my perspective, having done discourse analysis as a practicing high school teacher (e.g., ROTH & LUCAS, 1997), Applied Discourse Analysis provides an interesting collection of analysis. What it does not provide are examples of applied discourse analysis. WILLIG acknowledges these shortcomings but nevertheless does not question the approach chosen with this book—she suggests that doing discourse analysis constitutes a challenge to the status quo, and therefore already constitutes a form of political action. I tend to disagree because WILLIG does not acknowledge the difference HABERMAS (1971) articulated between practical interests, and emancipatory interests. Rather, I hold it with HABERMAS or MARX and ENGELS (1970) that the problem with the philosophers was in understanding the world (deconstructing it in the sense of "Abbau," taking it apart) rather than in changing it. Only change through emancipatory action embodies human agency as determined and determining, thereby forming a basis for theorizing praxis. WILLIG and her co-contributors have formulated a practice, discourse analysis, at a theoretical level and now promote its transfer to contexts other than the academe. In my view, we need to theorize "application" the other way around (e.g., ROTH, LAWLESS, & TOBIN, 2000). We need to begin in the midst of everyday life affairs, such as teaching, and then see how we can work out with others, resident practitioners, ways of critical analysis. In this, our work may well be informed by discourse analyses conducted in and for academic settings. However, we theorize these activities out of the praxis in which we are involved; theory then emerges as a talk about praxis, or, as I prefer to call it, praxeology. [9]

2.

One complaint I have concerns the lack of reflexivity. (See how the sidebar juxtaposes reader and text [Applied Discourse Analysis] thereby making a statement about their relation and introducing the reader, now turned writer, into his own text.) One might assume an author collective, writing about the discursive construction of the world, ought to use one or more techniques to relativize their own discourse. This is particularly astonishing given that there are examples from different domains, including The Reflexive Thesis (ASHMORE, 1989), Knowledge and Reflexivity: New Frontiers in the Sociology of Knowledge, or my own Lifeworlds and the 'w/ri(gh)ting' of classroom research (ROTH & McROBBIE, 1999). Readers who want to experience a reflexive argument immediately, may want to go to the penultimate version of the article Four dialogues and metalogues about the nature of science (ROTH, McROBBIE, & LUCAS, 1998). Such a reflexive stance appears to me rather important given the amount of constructive work (see ASHMORE & REED, 2000) that goes into the setting up and recording of interviews, transcribing and therefore translating lived conversations, and analyzing written transcripts. Furthermore, by writing themselves out of their narratives, the authors produce texts that I read as claims to truth rather than as evidence for the constructed nature of texts. [10]

Another complaint I have concerns the distance between theory and practice, discourse analysis as enacted by academics rather than by practitioners operating in their everyday settings. As the adjective applied in its title indicates, this book has the noble goal of moving discourse analysis from the citadel to the city—from a life as but another academic practice to a resource in the fight for social justice. Thus, the cover statement reads, "this book seeks to identify ways in which discourse analytic research can inform recommendations for social and psychological practice." Particularly, the editor Carla WILLIG suggests that the volume goes beyond traditional uses of discourse analysis by "formulating concrete proposals for social intervention" (WILLIG, ADA, p. 9). Accordingly, discourse analysis as social and political practice may take any one of three forms: social critique, empowerment, or guide to reform. Despite these laudable intentions, none of the authors really moves into the thickets of social or political action. The concrete proposals, if they are present at all, remain but proposals. I see very little difference in proposing other research and analysis tools. As long as the authors have not shown how discourse analysis is actually used in daily practice to make a difference, the authors should not claim that they do applied discourse analysis. There are examples how discourse analysis has been used by stakeholder groups in inner-city schools to analyze their situation and, by actively changing the context of their context, make a difference to the way they learn and teach (e.g., ROTH, LAWLESS, & TOBIN, 2000). Discourse analysis can also be used by high school students to become active agents in their learning and in the construction of their learning environments (e.g., DÉSAUTELS & ROTH, 1999; ROTH & ALEXANDER, 1997). However, the contributors to Applied Discourse Analysis do not show how the different human agents in their studies use discourse analysis in their concrete situation to make a difference. As we know from a number of studies in the social studies of science, skilled practice does not easily transfer from one situation to another even if practitioners are already skilled in a number of adjacent practices (e.g., JORDAN & LYNCH, 1998). Furthermore, when a practice actually gets "out into the wild," it may change in unforeseen ways so that new forms of practices develop—when science met AIDS activists, entirely new protocols for testing drugs evolved that were previously deemed to be unscientific (e.g., EPSTEIN, 1995). That is, "application" is a problem much more prickly than the authors appear to acknowledge or assume. To make this point even more strident: the skills associated with making a particular dish are not transferred from a three-star Michelin restaurant to some novice's kitchen just because a chef writes a book about it. Whether or not the recipe is feasible and leads to something edible has to be shown through examples of practical cooking in the lowly environs of a home kitchen. [11]

Although I do not consider that the editor and authors of this volume have brought discourse analysis to the struggle of the people, who use it as a form of emancipation in the way we had done with teachers and students in inner-city classrooms, I much prefer this volume over Critical Textwork. Following the tradition of discourse analysis, the authors provide examples that I would encourage the graduate students in my seminars and classes to read. Therefore I will use this book as a reference in my upcoming Interpretive Inquiry II seminar. [12]

Supplement III: Paul ten Have (1999). Doing Conversation Analysis

1.

From its beginnings with Harvey SACKS' (in)famous lectures in the late 1960s (posthumously published as SACKS, 1992a, 1992b), conversation analysis (CA) has developed into a mature discipline, one of the major methods of analyzing day-to-day verbal interactions, used in a variety of disciplines such as communications, education, anthropology, and sociology. [1]

I have come to know conversation analysis through my interests in ethnomethodology, and the close association of Harold GARFINKEL and Harvey SACKS, particularly through their On formal structures of practical action (GARFINKEL & SACKS, 1986). I became particularly fond of conversation analysis as a way of understanding the everyday world surrounding me, particularly how the social structures that others use to explain human conduct are actually instantiated in situated (inter)action. I had particularly enjoyed Chuck GOODWIN's (e.g., 1996) analyses in which he shows how color classifications or seeing become enacted in a collective way. Other enjoyable, book-length pieces showed how organization was talked into being (BODEN, 1994) or how fact, truth, and memory during the Oliver North Iran Contra trials were collectively achieved (LYNCH & BOGEN, 1996). Beyond these and other publications that used conversation analysis to articulate interaction order, I had not read any introductory texts or received any other formal instruction. [2]

I consequently looked forward to reading this introduction to conversation analysis. Throughout my reading, I thoroughly enjoyed the book, thinking both in terms of improving my own work and in terms of the students in my qualitative inquiry courses and advanced doctoral seminars, who would thoroughly appreciate this volume. [3]

2.

Doing Conversation Analysis contains 10 chapters divided into four parts: considering conversation analysis, producing data, analyzing data, and sharing data, ideas, and findings. In the first three chapters, Paul ten HAVE makes a fundamental argument for the use of CA by introducing practical exemplification of CA, a brief history of CA, a review of three classical CA studies, and basic methodological features of CA. In the second tier of chapters, Paul ten HAVE introduces readers to some general aspects of the research design of CA studies. These include sampling issues, naturalness and the question of additional data. A description of the nitty-gritty stuff in transcribing talk-in-interaction is the topic of Chapter 5. Here, the author addresses deals with the core of CA work, the careful, repeated listening to (and sometimes viewing of) recorded interaction in order to make detailed transcriptions of it, which subsequently serve as "data" for analysis. In the chapters of the third section, Paul ten HAVE focuses on the basic task of doing conversation analysis. Using concrete examples, he outlines some basic analytic strategies, elaboration of an analysis when multiple data excerpts require integrative work. The first three sections of the book more or less deal with issues of "pure CA," a form of analysis typical for linguistics departments. In the final section, Paul ten HAVE then turns to the issue of applied conversation analysis, which involves the CA-like practices in disciplines such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, or sociolinguistics. He sketches some of the problems and possibilities of applied CA but does not provide extensive instructions, as doing so would expand the scope of his book project. In the final chapter, Paul ten HAVE presents a variety of formats that can be used to make CA public and the techniques that readers may find useful in settings such as oral presentations, papers, and books. [4]

3.

In working through the issues of CA work, Paul ten HAVE provides the newcomer with descriptions of a number of the basic and fundamental issues in qualitative research, the "what to do" that is often omitted in other textbooks used during the teaching of qualitative research (e.g., GUBA & LINCOLN, 1989). How to record, how to get consent, and how to gain access to a variety of existing data are but some of the topics the author broaches. [5]

Each chapter contains a suggested activity ("Exercise") and recommended readings. Both features allow newcomers to focus their engagement with the topic, and get them started on relevant activities. I thought that the type of activity I personally engaged in would further enhance learning opportunities. As I already have large data sets, consisting of videotapes from science classrooms, professional scientific laboratories, and a variety of other settings, I was interested in immediately beginning to analyze some transcript. In particular, reading the book and fiddling around with my most recent data set, which is still under construction, I began to elaborate an analysis for an upcoming conference paper, Understanding laboratory communication. (Initial notes for this analysis, analyzed in DA-type fashion, can be found by clicking here.) [6]

Throughout the book, the author provides "demonstrations," that is, examples of doing conversation analysis rather than talking about doing conversation analysis. "Demonstrations," in ethnomethodological sense, require the reader to engage in the very activity that an article has as its topic. That is, "demonstrations" are reflexive allowing readers to experience doing as they are reading a description of their doing. My most favorite examples of this pedagogical approach were provided by BJELIC (1992) and BJELIC and LYNCH (1992), who involved readers in authenticating GOETHE's morphological theorem and his theories of prismatic colors, respectively. The "demonstrations" in Doing Conversation Analysis are of similar nature—though less elaborated and therefore easier to appropriate. These demonstrations are exemplary materials that allow students to reproduce the readings by comparing the transcriptions provided with the analysis. [7]

I also was pleased to read that transcribing involved a lot of ad-hoc reasoning and that Gail JEFFERSON herself took years to refine her transcription practices. Further, Paul ten HAVE points out that there may be differences in hearing the recorded sounds/ voices leading to differences in the transcriptions and possibly the analysis. As I read the chapter on transcribing, I experienced flashbacks to my early attempts in transcribing for a CA-type analysis and in measuring pauses, hearing overlaps, etc. In these early phases of my work, transcribing in ways so that I could reproduce timing, overlap, hearings, etc. was a real challenge. These challenges associated with translation from recording to written text are not hidden away, as in the two books on discourse analysis reviewed here, but explicitly addressed. [8]

4.

There are a number of things that I thought could have been done "better," more to my liking that is. I do not appreciate all to much when authors ventriloquize ([excessively] quote), making others speak through their pen. I always ask my graduate students to find and speak with their own voice. In my reading, Paul ten HAVE makes excessive use of quotations, which deterred me from fully appreciating his attempts in bringing CA closer to me, a member of his audience. [9]